Part 1 - Legal Developments

Banking and Finance

Draft laws published by the BRSA: The BRSA has published two draft laws on its web site. The first draft foresees various amendments in the Banking Law. The second draft foresees a new law on the establishment/operation of finance leasing, factoring and finance companies. We will follow the progress of these draft laws and update you on any legislative changes in future editions of the Turkish Update.

BRSA to decide minimum capital adequacy ratio for banks planning to set up off-shore branches or foreign partnerships.

An Amendment to the Regulation on Banking Activities subject to Permission and Indirect Shareholding was published on 23 January 2009. This amendment means the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency (BRSA) will from now on decide the minimum capital adequacy ratio that banks planning to set up off-shore branches or foreign partnerships should preserve.

Amnesty for black-listed debtors: According to a law published on 28 January 2009, the Central Bank of Turkey will clear its records of real persons and legal entities who have:

(i) defaulted in repayment of their loans;

(ii) issued bounced cheques;

(iii) debts arising out of officially protested deeds; and

(iv) credit card debts.

Clearance of the records will be subject to repayment or restructuring of the relevant debts by 28 July 2009. The law intends to provide comfort to firms currently experiencing liquidity and financing problems. However, financial institutions other than the Central Bank of Turkey are under no duty to clear their internal records.

Decrease in the rate of RUSF deductions: On 16 March 2009 the Council of Ministers decided to decrease the Resource Utilisation Support Fund (RUSF) deduction rate applicable to consumer loans extended by banks and financial institutions from 15% to 10%. RUSF deductions form a portion of the public revenues collected in Turkey over credit and import transactions carried out by banks and financial institutions. The Council of Ministers fixes the applicable deduction rate and exempts transactions from RUSF deductions.

Corporate and Commercial (including capital markets)

All types of capital market indebtedness instruments now regulated under a single Communiqué: on 21 January 2009, the Communiqué on the Registration and Sale of Indebtedness Instruments Serial. II No. 22 (Communiqué), replaced seven different communiqués and a circular. The effect of this is that all types of indebtedness instruments that can be issued in Turkey are now regulated by the Turkish Capital Markets Board (CMB) under a single piece of legislation. Some notable legislative changes made by the Communiqué are as follows:

- If issuers meet certain conditions under the new legislation they have more flexibility in the design of indebtedness instruments, as the CMB allows adoption of alternative structures other than those regulated under the Communiqué.

- The CMB can seek a warranty from issuers for their repayment obligations arising out of indebtedness instruments.

- All indebtedness instruments must be registered before the CMB (regardless of whether they are offered to public or not).

- The legislation introduces the idea of Exchangeable bonds (bonds exchangeable with shares of companies other than the issuer) into Turkish capital markets.

- The legislation abolishes the need for convertible bonds to be offered to the public.

Turkish listed joint stock companies can issue warrants: The Communiqué on the Registry and Purchase and Sale of Joint Stock Company Warrants published on 21 January 2009 enables Turkish listed joint stock companies to issue warrants.

Separate legislation for the public disclosure of material events by (a) listed and (b) non-listed Turkish public companies: Previously, the same communiqué regulated public disclosure requirements of both listed and non-listed public companies (which caused certain practical difficulties). Now the legislation about listed and non-listed public companies has been split into the following communiqués:

- The Communiqué on Public Disclosure of Material Events for Non-listed Public Companies Serial. VIII No. 57 was published on 6 February 2009. It regulates the procedures and principles of public disclosure of material events for non-listed public companies, which are less strict compared to listed public companies' disclosure obligations.

- The Communiqué on Public Disclosure of Material Events Serial. VIII No. 54 was also published on 6 February 2009. It regulates the procedure and principles of public disclosure of material events for listed companies.

- An new aspect of this legislation is that it distinguishes between material events which cause "internal information" or "continuous information" to form.

-

- the legislation defines "Internal information" as all types of information that may "have an effect on the value of capital markets instruments and investors' investment decisions". The communiqués do not specifically list events that may form such information. They refer companies to a guide, published by the CMB, which will help them understand material events subject to public disclosure.

- the legislation defines "continuous information" as all information outside the scope of internal information and subject to public disclosure requirements under the communiqués. The communiqués define material events which form "continuous information".

Broadening of the definition of "non-voting" shares: The Communiqué on Principles related to the Non-voting Shares Serial. I No. 36 was published on 21 January 2009. This repeals Communiqué Serial. I No. 30 and broadens the legislative definition of "non-voting shares" to shares granting:

- privilege on profit share;

- privileges (other than the privilege to buy shares for no consideration on demand) or privileges which provide management rights); and

- management rights except voting rights;

- the right to buy or exchange on demand a fixed or variable proportion of shares (which provide voting rights) in a company within a fixed term.

Private Equity Funds can carry out more activities in Turkey: The Communiqué on Principles related to Private Equity Investment Funds Serial. VI No.15 was amended on 21 January 2009 to enlarge the scope of activities which private equity investment funds can carry out . For example, private equity funds can now (amongst other things):

(i) invest in private equity investment funds settled in Turkey;

and

(ii) become a shareholder of consultancy firms settled in Turkey or

abroad which provide consultancy services related to private equity

actions carried out in Turkey.

Private Equity: "umbrella funds" and "sub-funds". The Communiqué on Principles related to Private Equity Investment Funds Serial. VII No.10 was amended on 21 January 2009. The amendments introduce the concepts of "umbrella funds" and "sub-funds" to the legislation, and contain terms on the set-up and operation of "umbrella funds".

Tighter controls on cancelling cheques: Article 32 of the Law No.5838, has repealed Article 711/3 of the Turkish Commercial Code (which was previously misused by cheque issuers) to prevent cheque issuers from being able to cancel cheques in certain circumstances.

Employment

Allowance for work hours decrease/suspension: A Regulation published on 13 January 2009 sets out principles and procedures for a work allowance payment to employees in cases of:

(i) temporary deduction of weekly working hours by the employer;

or

(ii) temporary suspension of the operations due to an economic

crisis/force majeure circumstances.

Insurance

Foreign assets which may be presented as technical reserves of insurance, reinsurance and pensions companies: A communiqué on this subject was published on 21 January 2009 and sets out principles and procedures related to presenting:

(i) financial assets issued by foreign companies;

(ii) foreign deposits; and

(iii) real properties located in foreign countries, as technical

reserves of insurance, reinsurance and pensions companies

Criteria for insurance arbitrators and procedures for insurance arbitration. The Communiqué on Insurance Arbitration Procedures and Insurance Arbitrators which was published on 21 January 2009 sets out criteria for insurance arbitrators and procedures for insurance arbitration.

Approval of reinsurance strategies: The Regulation on Financial Structures of Insurance, Reinsurance and Pensions Companies was amended on 1 March 2009 to require the board of directors of an insurance company to approve the reinsurance strategies for the following financial year.

New ratios to calculate transferred insurance risks. The Regulation on Measurement and Calculation of Capital Adequacy of Insurance, Reinsurance and Pensions Companies was amended on March 1 2009. The amendments provide new ratios to calculate transferred risks (including those transferred to reinsurers or reinsurance pools).

Life Insurance: amendments re: General Directorate of Insurance tariff: The Regulation on Life Insurance was amended on 13 January 2009 to enable life insurance companies to decide expense amounts and intermediary commissions according to the specifics of the relevant General Directorate of Insurance tariff. Further, for life insurance agreements which are terminated before the expiry of the relevant "purchase term" the total amount of the accrued part (including all interest on it) of tariff premiums paid before the termination date, will be paid back to the insurer after various deductions (determined by the life insurance company based on the total proportional amount). The relevant insurance tariff itself is also amended.

Competition

1.1 Legislation

Groundbreaking change in fine-setting system under Turkish Competition law. On 15 February 2009, the Turkish Competition Authority (TCA) published:

(i) the Regulation on Monetary Fines for Abuse of Dominant Position and/or Restriction of Competition via Agreements, Concerted Practices or Decisions of Association of Undertakings (Fine Regulation); and

(ii) the Regulation on Active Cooperation for Revealing Cartels (Leniency Regulation).

These Regulations follow various amendments in 2008 to the fining terms of the Turkish Competition Act and together, this legislation makes welcomed and important clarifications to the fine-setting regime which applies to Turkish competition law violations. For further detail on these Regulations please see our article "A Groundbreaking Change in Fine-Setting System under Turkish Competition Law". This article was also published in several legal journals and sent out with the brochure of the Denton Wilde Sapte Competition Law Network.

1.2 Recent formal investigations of the TCB

(a) In the automotive sector. On 8 January 2009

the TCB launched a formal investigation onto 56 dealers of Peugeot

Automotive. On 25 February 2008 , the TCB launched a formal

investigation on 41 dealers of Citroen Automotive. The TCB will

examine whether a system launched by the Peugeot/Citroen dealers

which fixed prices and sales conditions is a cartel abuse or not.

These investigations do not affect Peugeot/Citroen only the

relevant dealers.

(b) In the medical services market. On 8 January

2009, the TCB gave its final decision following its investigation

of certain companies in the dialysis medical services market for

their practices in bidding in certain public tenders. The TCB has

subsequently decided there is not enough evidence of abusive cartel

conduct and closed this investigation.

1.3. Other Important Decisions of TCB

(a) In the Telecommunication and Internet Technology Sector. The TCB decided not to open a formal investigation against Turk Telekom and its subsidiary in the internet sector TTNet after completing a preliminary investigation on 18 February 2009. However, in the same decision the TCB noted there is a violation of competition rules by Turk Telekom and TTNet making "tying arrangements" between direct phone lines and ADSL (as they are both in the same economic unity and have a dominant position in internet service providing market). The TCB gave Turk Telekom/TTNet 3 months to end their "tying arrangements" and provide customers with the ability to subscribe to the internet through other lines (rather than a combination of direct phone lines and ADSL).

(b) In the Fuel-Oil Distribution Sector. The TCB clarified its view about fuel-oil distribution contracts by a decision on 5 March 2009. In this decision the TCB banned fuel distribution contracts between oil companies and retailers (petrol stations) that are for a longer term than 5 years. Oil companies have been evading this limit by entering usufruct arrangements on the land of retail stations for periods of between 15 and 40 years. The TCB has declared these usufruct arrangements invalid. The TCB has given the parties a transitory period until 18 September 2010 to correct the "term clauses" of distribution contracts or usufruct arrangements. This decision will create various compensation issued between dealers and oil companies.

Telecommunications

Groundbreaking changes in the Telecoms law. A new regulation, which will replace the currently in force Authorisation Regulation on the Telecommunications Services and Infrastructures, will be published in the Official Gazette around mid-May. This regulation will provided ground-breaking changes as the ECL drastically changed the regime of authorisation under Turkish telecom law. We are following this regulation closely and will report on it in the next edition of The Turkish Update.

Regulation on Electronic Communication Security: Slightly amended by the Information Technologies and Communication Authority (ITCA) on 2 March 2009. The purpose of the amendment, which does not have a significant content, is to ensure compliance with the new Electronic Communication Law (ECL).

Energy and Infrastructure

Nuclear

- Amendment to the Regulation on the Quality Management for the Safety of Nuclear Facilities: Published on 17 February 2009. A new temporary provision has been added to this Regulation which states that nuclear facilities that have an operating license (or applied for a permit or licence after 13 September 2007) should submit documents on quality and configuration management systems by 13 September 2010.

- Abolition of Regulations: The following

regulations were abolished:

(i) Regulation on Quality Security in Studies about Choice of Location for Nuclear Power Stations;

(ii) Regulation on Preparation and Execution of Security Guides Settling Security Principals in Nuclear Facilities; and

(iii) Regulation on Preparation, Acceptance, Execution and Amendment of Nuclear Security Series Documents. A broader regulation (the Regulation on Quality Management Main Requirements for the Safety of Nuclear Power Stations) now deals with the issue that Regulation (i) covered, and internal circulars prepared by the Turkish Atomic Energy Authority now deal with the issues covered by Regulation (ii) and (iii).

Security principles re: land on which a nuclear station can be placed: These are set out in the Regulation on Nuclear Power Station Grounds which was published on 21 March 2009.

Dispute Resolution/Arbitration

Civil participation into the legislative proceedings: The Turkish government supports the civil participation into the lawmaking process by the approval of a Project signed with the United Nations Development Program. The program enables non-governmental organisations access to legislative proceedings, and increases the exchange of information between them and the Turkish parliament.

Insolvency/Debt Restructuring

Simplification of sales by the Savings Deposit Insurance Fund (SDIF): Under the Regulation amended on 31 March 2009, the approval of the Board of the SDIF is not needed for sales below an amount that the Board will decide.

Real Estate

Infrastructure Real Estate Investment Trusts: A Communique (Serial. VI, No: 24) published on 29 January 2009 sets out detail on the following principles and procedures for Infrastructure Real Estate Investment Trusts:

(i) founding shareholders and establishment procedures;

(ii) operation licences of portfolio management;

(iii) organisation;

(iv) registration of capital markets instruments to be issued;

and

(v) the duties about public disclosures.

Temporary Cabinet decisions on registration charges and VAT:

- Decision Numbered 2009/14812: Published on 29 March 2009 and will be effective until 30 June 2009. Reduces the registration charges from 150 to 50 on the certain land registry processes (e.g. property acquisitions, establishment of easement rights, etc.). The decision reduced VAT to 8% for the delivery of certain types of workplaces.

- Decision Numbered 2009/14802: Published on 16 March 2009 and will be effective until 15 June 2009. This decision reduces the VAT from 18% to 8% for real properties which have a net area of 150 m2 or more.

IP/Technology

Legislation to fill the legal gap re: protection of trademark rights: The Law No.5833 Amending the Trademark Decree on 28 January 2009 (Law No.5833) fills the legal gap which appeared after the Constitutional Court had abolished certain terms of the Trademark Decree. The Constitutional Court abolished the Decree because it infringed the basic principle under the Turkish Constitution which states that acts of infringement with criminal sanctions apply need to be regulated by a legislative "act/law" not by a "decree".

Guner Law Office was established in 1996 and has since grown into one of the major corporate, M&A, banking, litigation, energy and TMT practices in Turkey. Guner Law Office is headed by Ece Guner and works with international law firm Denton Wilde Sapte.

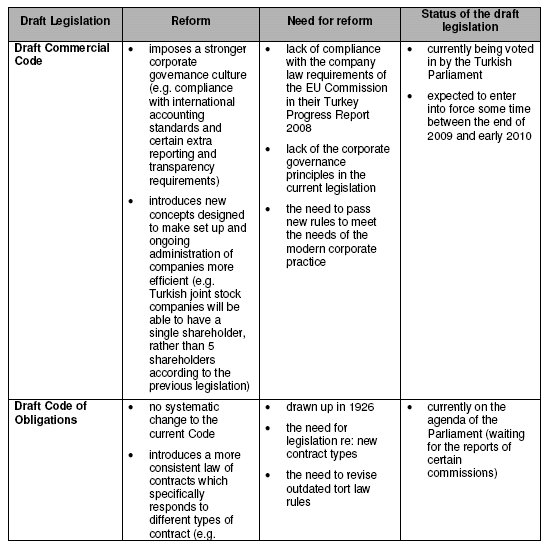

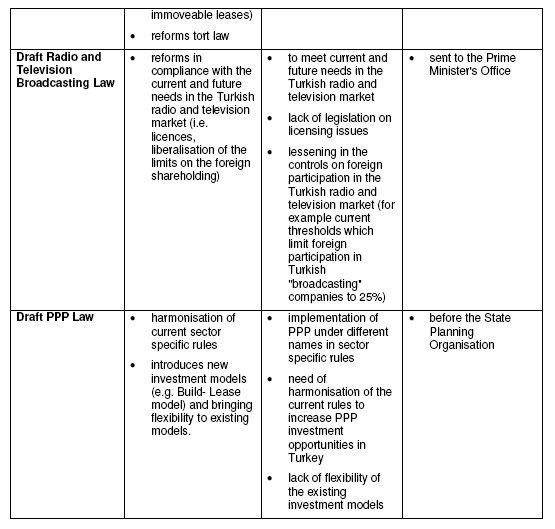

Part 2 - "Hot Topics"

Speeding up reform

We set out below a table containing brief notes on some ongoing and potential legislative acts which, if completed in 2009, should help to modernise Turkish legislation and improve the overall investment environment.

Debt Restructuring: The way ahead in Turkey

Background

The Turkish economy entered a financial crisis in November 2000 and in February 2001 the crisis peaked and triggered a collapse in the value of the Turkish Lira. Over a few days, the Turkish Lira lost more than 40 percent of its value against the major trading currencies and interest rates rose spectacularly overnight. As result of this crisis a significant number of Turkish companies became bankrupt.

As the Turkish economy was recovering, the Turkish government then looked carefully at the existing legislation and practices related to non-performing debtors. As a result, new laws were introduced enabling non-performing debtors, in certain cases, to avoid bankruptcy and providing certain advantages to creditors. These new laws were introduced in 2003 and 2004 by amendments to the Turkish Execution and Bankruptcy Law ("EBL"), which is the principal legislation setting out enforcement proceedings. These amendments introduced the following new procedures into the EBL: Postponement of Bankruptcy ("Postponement"), Reorganisation by Abandonment of the Debtor's Assets ("Reorganisation") and Restructuring of Capital Stock Companies by Conciliation ("Formal Restructuring").

It was not only the attitude of the Turkish lawmakers that changed related to non-performing debtors. With experience gained through the financial crisis, financial institutions recognised that a knee-jerk reaction of enforcing security or starting insolvency proceedings related to a defaulting debtor is not always the best solution. It became clear to financial institutions during this crisis, that it can at times make more commercial sense to take part in a restructuring with their customers experiencing financial difficulties instead of following conventional enforcement proceedings. A significant number of Turkish financial institutions entered a consensual framework agreement and signed separate debt restructuring agreements with debtors to restructure their debtors' unpaid debts. This consensual debt restructuring arrangement was known as the "Istanbul Approach". Following the success of the Istanbul Approach, Anadolu Approach followed. Anadolu Approach was also a debt restructuring method similar to Istanbul Approach but, different in the sense that where Istanbul Approach aimed at restructuring the debts of major enterprises, Anadolu Approach aims at restructuring the debts of small and medium size enterprises.

What is debt restructuring? Why restructure?

Debt restructuring (otherwise known as "turnaround" or a "workout") describes a process whereby a company facing financial pressure will agree with its lenders and principle creditors a new contractual framework for financial support involving a restructuring and/or rescheduling of the company's bank facilities and other debt obligations. By comparison, under the Postponement, Reorganisation and Formal Restructuring procedures, parties must comply with the applicable framework of the EBL, which is less flexible than consensual debt restructuring and in Reorganisation and Formal Restructuring, the implementation of such by the Turkish courts remains to some extent uncertain because these recently introduced procedures have been rarely used to date. Postponement has however been de facto applied under Turkish law even before its introduction into the EBL and is the most commonly used formal procedure to avoid bankruptcy. Postponement therefore may provide an alternative to consensual restructuring. However, Postponement will require an application to the court for the company to be declared bankrupt and a subsequent decision by the court to postpone such bankruptcy.

An important feature of a contractual debt restructuring is that usually a bankruptcy process and court involvement related to the company is avoided. The company continues to trade often with a view to implementing a new business plan under which it will make fundamental changes to its cost base and business.

By avoiding a bankruptcy, and choosing debt restructuring over other formal procedures the following advantages can usually be expected:

- adverse publicity associated with a bankruptcy may well have a damaging effect on the company's business and its realisable asset values. This often arises because of the view by a buyer that the company is desperate to sell and therefore the buyer has increased bargaining power. There may also be adverse publicity for a lender if for example it pushes a high profile, nationally significant customer into a bankruptcy process

- termination rights found in the company's contracts and licences are less likely to be exercised

- the costs associated with running a bankruptcy or court-driven rescue process such as Postponement, Reorganisation or Formal Restructuring can be high and the procedures be time consuming

- directors and management may face financial ruin in a bankruptcy process either because all their wealth is tied up in the bankrupt company or because they have given personal guarantees to creditors or because they could face disqualification from taking part in the future management of another company.

Are debt restructurings suitable in all cases?

If a debt restructuring is to have a prospect of success, creditors must be able to come to an informed view that it will give them a better return compared to other alternatives. There may be some circumstances where the prospects of a successful debt restructuring are doomed from the start. For example, when the problems of the company are too severe for a recovery to be feasible or the business of the company is not economically viable. In these cases, the creditors' interests would be best served by enforcing security or starting a bankruptcy process.

The key players in a restructuring

The company and its directors

The company's management play a key role in a restructuring. Their task is to win over the creditors who are going to be asked to give up or vary their contractual claims. If the current management is not up to the task, they (or the creditors) should consider bringing in specialist expertise. For instance, in many jurisdictions, companies in complex restructurings will engage a chief restructuring officer ("CRO") who will represent the company in the restructuring negotiations with the creditor group.

The management will also have the responsibility for preparing the business plan in which the financial weaknesses of the company are to be addressed in an acceptable timetable. Therefore, the company and management may need the services of accountants or turnaround specialists who will be able to advise it on its business and how its financial performance and profitability can be improved.

The company and management will also need legal advice. Not only will the legal advisors help the management with the drafting and negotiation of the restructuring documentation but they will also advise on directors' duties and responsibilities, an area which assumes a special importance where the company is facing possible bankruptcy. Under Turkish law, transactions conducted by a company before the company being declared bankrupt can be reviewed in a bankruptcy process and can be challenged and then in certain cases overturned. Directors may also face personal liability for making the decisions that they did while the company was under financial hardship and was negotiating a restructuring. For those reasons, proper legal advice is essential.

Management may also need to ensure that where the company's shares are listed on a stock exchange, the company complies with its listing duties. In accordance with capital markets legislation in Turkey (Capital Markets Board Communiqué numbered VIII/39) listed companies are under various disclosure duties e.g. to announce to the market related to any matters which could have a material impact on the share price and as to any substantive debt restructuring arrangements. The disclosure process and satisfaction of listing duties will need to be carefully monitored and handled.

The principal creditors

The banks and bondholders

In most restructurings, the bank lenders to the company are at the centre of the process. Almost certainly, there will be several lenders either under separate facility arrangements and/or because a particular facility has been syndicated among a number of banks. There may be a complex array of banks each having exposures under different facilities and in different currencies; there may be domestic and foreign banks; those which are secured and unsecured.

Many companies now seek debt financing outside the settled banking community. Since bond financing (e.g. Eurobonds and medium-term note programmes) is becoming increasingly used in Turkey, bondholders will now require a place at the negotiating table. The importance and prelevance of bondholders can be seen in some of the largest of the restructurings around the world. Those of note include the restructuring of NTL, Marconi, Parmalat, British Energy and the Republic of Argentina.

Other creditors and employees

A restructuring is less likely to involve other creditors such as the tax authorities, social security department, landlords and suppliers. The restructuring process will usually contemplate that these creditors will be paid in full. It is also unusual for employees to be involved in a restructuring. However, they can be indirectly affected by it even if their consent to it is not required. The company's business plan may involve a decrease in the workforce or an adverse change to employees in their terms and conditions of employment and certain laws will need to be considered. Article 29 of the Labour Law in Turkey provides that in the event of a major reduction in the workforce of a company the company is required to notify certain governmental authorities.

Professional advisors

As well as the company and the creditors, professional advisors are likely to have a key role in the restructuring. We have already mentioned the need for the company and the management to have proper legal representation. The other parties to the restructuring are also likely to need legal advice to represent their individual and separate interests in the restructuring. The lawyers acting for the different sets of creditors are likely to be involved in legal due diligence, agreeing confidentiality agreements, drafting and negotiating the restructuring documentation including new facility and security agreements and advising on "plan B" strategies, such as advising on bankruptcy processes and methods of enforcing security.

Other professional advisors will feature in many restructurings. The banks and bondholders may appoint their own financial advisors to help them in understanding the company's financial information and prospects and to advise them on the financial implications of the company's restructuring plan.

Shareholders

It may seem strange to mention shareholders as a party in a restructuring. They will often be the last people to receive a return in a bankruptcy. If the company is listed, it will be subject to capital markets legislation which may, in certain cases, require shareholders' consent (e.g. Capital Markets Board Communiqué numbered I/31) where the restructuring plan involves a major asset disposal programme.

What are the principal steps in a restructuring?

Most debt restructurings involve the following stages:

- the organisational stage

- signing confidentiality agreements and negotiating the standstill agreement

- agreeing the restructuring plan and negotiating the restructuring documents to effect the plan " performing the plan

The organisational stage

For the company, this will involve appointing professional advisors (in particular lawyers) and possibly, a CRO.

The bank group will need to organise themselves to conduct the restructuring negotiations. The lead or agent bank will therefore form a steering committee. The lead or agent bank will be the bank which has been given that role in the original loan documentation and will often be the bank with the largest exposure or the bank which originally negotiated the loan before it was syndicated. The steering committee will consist of certain syndicate banks and will be authorised by the syndicate to decide on its behalf. For example, the committee will be mainly responsible for negotiating the standstill agreement and the restructuring documents although in both cases, the documents will usually have to be made conditional on each member of the bank syndicate obtaining its own necessary internal approvals.

Once the participants in the restructuring (e.g. banks, bondholders) have organised their representation for participating in the restructuring process, the management will wish to meet with the various creditors' committees as a matter of urgency.

Confidentiality and standstill agreements

Confidentiality agreement

An early step in the restructuring process is for the company to agree confidentiality agreements with the creditors taking part in the restructuring process. Once the confidentiality agreements are signed, the company can start sharing information with the creditors about its business and affairs and about the other participants' claims against the company.

The standstill agreement

The next critical step is to agree the standstill agreement. The purpose of the standstill agreement is to give the company and the creditors a defined window of opportunity to agree a restructuring deal and for the creditors to carry out due diligence work without the risk of the process being undermined by creditors exercising their remedies or forcing the company into a bankruptcy process. The main areas which will usually be covered by a standstill agreement are as follows:

- an undertaking by the creditors to continue the facilities on the terms and the limits available at a specified date (the standstill date)

- repayment of interest to the creditors will be dealt with in some way. It may be that creditors will waive or defer interest for the standstill period

- an agreement that the creditors will not take any further security to improve their position

- a standstill period will be specified with the ability to extend it, with appropriate consent

- crucially, there will be an agreement by the creditors to enter into a stay or moratorium. This will mean that the creditors will not during the standstill period take action to enforce security, to make demand or speed up loans or other debt claims, to bring legal proceedings (including any insolvency proceedings) against the company and possibly, not to exercise rights of set-off. It should however be noted that a standstill agreement will not prevent a party exercising its rights under general Turkish law and in particular under the EBL including initiating any bankruptcy proceedings or enforcing any security interest. This is because a party can still exercise its rights under Turkish law notwithstanding that it has agreed to waive or postpone such rights under a standstill agreement. However, a party could expose itself to breach of contract claims from the other parties to the standstill agreement if they suffer damages because of such party's failure to comply with the terms of the standstill agreement. The risk of significant potential liability for any failure to comply hopefully will ensure full compliance by all parties to the terms of any standstill agreement.

- events of default which will cause the standstill period to end early

- there may also be an agreement concerning emergency short-term financing to be made available to the company.

What does a debt restructuring plan look like?

Once the standstill agreement has been signed, the next stage is to negotiate the final restructuring deal. At the same time as this is being done, the company should provide due diligence materials to the creditors. A thorough and well-organised communication process between the company and the creditor body is essential. When it comes to negotiating the detail of the restructuring plan, there are no hard and fast rules. The deal, if it is to work, will have to reconcile several reasons. The company will need a realistic period to turn around its business and address its financial weaknesses. What is realistic will depend on the depth of the problems and the steps needed to resolve them. Financial protections, cashflows and valuations will be vital information that needs to be taken into account to enable creditors to find out if the company needs new money to survive. Creditors will also want to know that the deal will leave them with a better result compared to alternatives. In particular, they will want a view about their estimated recovery in a bankruptcy procedure.

A restructuring plan may also involve new or restructured credit facilities, loss sharing arrangements among all or some of the creditors related to new facilities, raising money from the shareholders, subordinated debt, sale and leasebacks and other financial instruments.

The future of debt restructuring in Turkey

As Turkey continues to attract foreign investment, those investing in the Turkish market will expect a system which supports their expectations in dealing with a defaulting customer. With this in mind, the Turkish governments have taken significant steps since the 2000/2001 financial crisis to create such a system by introducing the Postponement, Reorganisation and Formal Restructuring procedures into Turkish law. However, these formal procedures can be time-consuming, costly, inflexible, at times uncertain in their implementation and do not always provide the best solution. Consensual debt restructuring can be more responsive to the needs of the market. The Istanbul Approach has enabled the financial institutions involved in such restructuring to recover most of their outstanding debts which they might not otherwise have been able to recover. There is every reason to believe that Turkish companies and financial institutions will continue to recognise the benefit that consensual restructuring can provide as an alternative to following formal proceedings related to non-performing debtors.

A Groundbreaking Change in Fine-Setting System Under Turkish Competition Law

On 15 February 2009, the Turkish Competition Authority (TCA) published a "Fine Regulation"1 and "Leniency Regulation"2 which follow various amendments in 20083 to the fining provisions of the Turkish Competition Act. Together, this legislation makes welcomed and important clarifications to the fine-setting system which applies to Turkish competition law violations.

This Article summarises the nature and characteristics of this new system and shows how it goes some way towards dealing with criticisms of the old system.

Compliance with EU legislation?

The new Regulations introduce "sentencing guidelines" and a "leniency program" to the Turkish competition law enforcement system. This ensures further compliance with the recommendations of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD),and the relevant legislations of United States of America and European Union (EU), who require an effective fining system for competition violations, especially for cartels.

Turkey, as part of its EU membership process, aligns its competition law with EU legislation. Therefore, the Turkish Competition Act, in parallel with relevant European Council (EC) Regulations4, provides that the Turkish Competition Board (TCB) can impose an administrative fine of up to 10% of the last fiscal year's turnover of a relevant undertaking which violates Turkish competition law.

The new Regulations, again in parallel with EC legislation, attempt to clarify how this administrative fine will be applied by the TCB. However, they do not exactly reflect the latest EC position, introducing a finesetting system which is a mix of old and new EU legislationi. Therefore, although the Regulations go some way towards greater compliance with EU legislation, they do not go the whole way.

Scope of the Regulation

The Fine Regulation introduces a fine-setting system which the TCB can impose on undertakings which violate Turkish competition law by creating cartels or abusing their dominant position. This system also sets out fines which can be imposed on managers or employees of these undertakings who are involved in such violations.

The Leniency Regulation introduces new rules to be applied to undertakings and their managers or employees who actively cooperate with the TCA by providing information in relation to cartels in the Turkish market. This Regulation does not apply to violations of Turkish competition law which result from (a) the abuse of a dominant position in the relevant market; or (b) vertical agreements which breach competition rules.

The Regulations do not establish a fine system for monopolisation as a result of mergers and acquisitions in the Turkish market. They also do not set forth rules in relation to fines which can be applied for the following procedural violations:

- submitting misleading information when making exemption or negative clearance notifications or merger and acquisition notifications to the TCA;

- making mergers and acquisitions without the TCB's consent when such transactions are subject to the TCB's approval;

- not providing the documents and information required by the TCA during an investigation or providing misleading information; or

- preventing the on-site investigations of the TCA.

As specific rules are not set out in the Regulation for these procedural violations, the general fine percentages set out in the Turkish Competition Act will applyii.

Finally, the Regulations do not cover periodical finesiii which are imposed for (i) non-compliance by relevant undertakings to commitments/obligations arising from injunction or final decisions of the TCB; (ii) the prevention of on-site investigations; and (iii) delay in provision of required documents and information to the TCB.

Narrowing the TCB's discretion in determining fines

The most important change brought by the new Regulations (which implement the latest amendments of the Turkish Competition Act) is that they clarify and narrow the TCB's discretion in the determination of fines for the violation of Turkish competition law. They do this by basing the TCB's discretion on more relevant competition law principles and setting out detailed provisions on the types of fines that can be made so that fines are more appropriate to the relevant violation.

Before the new system was introduced the TCB's discretion in determining fines was based on criminal law principles (such as the intention of the undertakings violating the competition law, the degree of their fault, their power in the relevant market, and the degree of potential damages). However, under the new system the TCB's discretion is applied to principles which are based on competition law practice (such as the repetition of the violation and its duration; the power of the undertaking/association of undertakings in the relevant market; the influence of the undertaking in the decision-making process which led to the violation of competition law; an undertaking's compliance with any conditions imposed on it by the TCB; and the importance of the current or potential damage).

Previous TCB fines had been criticised for not being appropriate to the relevant violation and Turkish competition legislation was criticised because it did not contain clear, transparent and objective rules for the determination of fines by the TCBiv. For example the TCB had previously:

- in general issued fines of 1-3% of turnover to undertakings violating competition legislation (despite the 10% threshold).

- imposed relatively low fines on:

-

- long-term cartels in iron-steel sector despite the relevant undertakings in this sector having very high turnoversv.

- undertakings which breached very serious provisions of competition law (such as an abuse of a dominant position in the relevant market)vi.

The new fine-setting system in the Regulations responds to these criticisms as the TCB will now apply a focussed, objective criteria for each violation of competition law. This will also ensure transparency for the undertakings who are subject to fines as they will be able to foresee and calculate the fine that could be imposed on them.

Therefore, the previous fine-setting practice of the TCB (which in the 12 years prior to the Regulations was heavily criticised as being inefficient) has ended. The TCB will now have to apply specific rules for each competition law violation, regardless of the relevant undertaking's turnover.

The new fine system Article 4 of the Fine Regulation sets out the main principles for the determination of fines by the TCB which are as follows:

- each act resulting in violation of competition law will first be subject to a basic fine (the Basic Fine) which is a percentage that will be increased or decreased depending on whether there are aggravating or mitigating circumstances.

- More specifically, the initial percentage of Basic Fine will first be increased if there are any aggravating circumstances. Then, if there are any mitigating circumstances, either the initial percentage of Basic Fine or the increased Basic Fine as a result of the aggravating circumstances will be decreased (depending on the relevant clause of the Fine Regulation).

- any fine will be capped at 10% of the last fiscal year's turnover of the relevant undertaking. " a fine on an association of undertakings will be calculated on the turnover of each undertaking (as opposed to previous practice which was based on the turnover of the association of undertakings).

- any fine calculated by the TCB under the Fine Regulation will also be evaluated under the Leniency Regulation.

Article 5 of the Fine Regulation sets out the rules for calculation of the Basic Fine:

- in making this calculation the TCB shall consider the market power of the undertakings, the degree of the damages, and other competition law criteria.

- undertakings creating a cartel will have a Basic Fine of 2-4% of their turnover, whereas undertakings which have made other competition law violations will be subject to a fine of 0.5-3% of their turnover.

- the Basic Fine will be increased depending on the duration of the violation. The Basic Fine will be increased by 50% for violations of 1-5 years and it will be increased by 100%vii for violations which have persisted for longer than 5 years. For example, the basic fine for undertakings creating a cartel of 5 years will be 4-8% of their turnover.

Article 6 of the Fine Regulation sets out aggravating factors which may/shall increase (as some of the increases are at the discretion of the TCB whilst others are mandatory) the Basic Fine. Under this Article the Basic Fine:

- shall be increased by 50-100% if an undertaking repeats or continues violations despite the initiation of an investigation by the TCA; and

- may be increased by 25% if an undertaking is a "leader" of a violation;

- may be increased by up to 50% if an undertaking does not assist the TCA during its on-site investigations.

- may be increased by 50-100% if an undertaking does not comply with any conditions imposed on it by the TCB; Article 7 of the Fine Regulation sets out mitigating factors which may/shall decrease (as some of the decreases are at the discretion of the TCB whilst others are mandatory) the fine.

Under this Article:

- the Basic Fine may be decreased by 25-60% if any undertaking (i) assists the TCA with its investigation; (ii) was forced by other undertakings to commit such competition law breaches; (iii) was encouraged by public authorities to behave in breach of competition rules; (iv) has indemnified other undertakings facing damages; (v) stops violations other than cartels; or (vi) proves that its turnover in the relevant market is insignificant in proportion in its total turnover.

- the increased Basic Fine as a result of any aggravating circumstances (as relevant) shall be decreased by 25% if an undertaking informs the TCA of a cartel that it was not previously aware of (even if this undertaking cannot benefit from the Leniency Regulation); and

- the increased Basic Fine as a result of any aggravating circumstances (as relevant) shall be decreased by 15-25% if an undertaking accepts the violations other then cartels and actively cooperates with the TCA.

Article 8 of the Fine Regulation sets out fines which will be applied to managers or employees of the relevant undertakings. This fine has no minimum level, except for in the case of cartels where the minimum level will be 3% of the fine imposed on the undertaking. It is capped at 5% of the fine imposed on the undertaking.

The newly introduced leniency system

As mentioned above, any fine calculated by the TCB under the Fine Regulation will also be evaluated under the Leniency Regulation. The Leniency Regulation enables undertakings who actively cooperate with the TCA (and their managers/employees) to be exempt from fines or have their fines reduced.

Actively cooperating undertakings will be exempt from fines if they:

- report a cartel to the TCA (before the TCA is aware of it); or

- submit evidence which enables the TCA to prove a violation (whilst an investigation is going on and which the TCA would not be able to find in such an investigation).

Only the first undertaking (and their managers/employees) which makes such a report or submits such evidence will be exempt.

Actively cooperating undertakings will have their fines reduced if they submit relevant evidence during an ongoing cartel investigation by 50% (if they are the first undertaking to submit such evidence); 25-35% (if they are the second such undertaking); or 15-25% (if they are the third or subsequent such undertaking). This leniency system also applies to managers or employees of a relevant undertaking but the upper limit of the reduction is 100% (rather than 50%) so as to incentives managers/employees to provide such evidence.

A relevant undertaking, manager or employee (the Applicant) will only benefit from the exemptions or reductions described above in relation to cartels if it submits the names of undertakings which are party to that cartel and other relevant documents which are set out in further detail in the Leniency Regulation. The Applicant should also:

- not hide or destroy any relevant evidence;

- cease to be a party to the cartel (unless otherwise requested by the TCA);

- keep the submission of evidence confidential (unless otherwise requested by the TCA); and

- continue to actively cooperate with the TCA until it renders its final decision.

Therefore the TCA has the ability to keep an Applicant in a cartel so that this Applicant can continue to provide evidence to the TCA about the cartel and its operations. Please note that an Applicant who is the "leader" of a cartel can only obtain a fine reduction and not an exemption.

A special unit, headed by the TCA's Vice President, was established on 19 February 2009 in order to deal with such applications/submissions by an Applicant. Applications need to be made to the TCA in writing (but in certain cases the TCA will accept verbal declarations as long as they are registered by the TCA) and following the submission of evidence, the TCB shall render its decision on the relevant exemption/reduction and apply this to any fine.

Application of the Regulations

The Regulations apply to all future TCA investigations. They also apply to ongoing TCA investigations but will not apply to ongoing investigations where an investigation report has been submitted to the TCB. Therefore the practical impact of the Regulations will be evident within this year (as there are currently newly-initiated ongoing TCA investigations which are subject to the Regulations).

Conclusion

The Regulations will result in higher monetary fines being levied against undertakings which violate Turkish Competition Law, and this will bring Turkey in line with other EU countries. This will answer critics of the previous fine system under Turkish competition law. It will also ensure greater compliance with Turkish competition law as undertakings (mindful of the potential fines, which they can now calculate more easily) take active or even preventative measures to ensure that they comply.

However, uncertainties remain in relation to how the TCB will determine fines for competition law violations by undertakings which form a single economic entity (for example groups of companies). Under the new system (as under the previous system) fines are calculated on the overall turnover of the relevant undertakings (whereas in the EU the calculation is based on the turnover of the undertakings in the relevant market). Therefore, further clarity is needed as to how the TCB will determine which legal entity amongst various legal entities forming a single economic entity will be subject to fine as an undertaking violating the competition law. For example, if a holding company is involved in several product markets, it is possible that the fines are imposed on undertakings belonging to this holding who are not involved in the relevant market where the violation has occurred. In addition, if there is no legislative clarity on which undertaking is subject to the fine, it is difficult for the TCB to determine which undertaking is repeating any given violation.

Nevertheless, as the system introduced by these Regulations is clearer and more comprehensive than the previous system, it will help in improving the competition culture in Turkey and through the Regulations Turkish Competition law has made progress and become more effective.

Footnotes

1 "Regulation on Monetary Fines for Abuse of Dominant Position and/or Restriction of Competition via Agreements, Concerted Practices or Decisions of Association of Undertakings"

2 "Regulation on Active Cooperation for Revealing Cartels"

3 Amendment to the Law No. 4054 on the Protection of Competition (the Turkish Competition Act) by the Law dated 23 January 2008 and numbered 5728. For the brief information about this amendment see the article; "Turkey: The Turkish Update - 1st Quarter, 2008" published by Guner Law Office.

4 Article 15 (2) of EC Regulation No 17 and Article 23(2)(a) of the EC Regulation No 1/2003.

i The "sentencing guidelines" were introduced to the EU legislation in 1998 (Guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 15 (2) of Regulation No 17 and Article 65 (5) of the ECSC Treaty. Official Journal C 9, 14.01.1998). The Guidelines were amended in 2006 (by the Guidelines on the method of setting fines imposed pursuant to Article 23(2)(a) of Regulation No 1/2003. Official Journal C 210, 1.09.2006, p. 2-5). The "leniency notices" was introduced to the EU legislation in 1996 by the Commission Notice on the non-imposition or reduction of fines in cartel cases, which was amended in 2002 and 2006 (amendment by the Commission notice on immunity from fines and reduction of fines in cartel cases).

ii This percentage is five per thousand of the revenue in the case of prevention of on-site investigations and one per thousand for other violations.

iii This percentage is five per ten thousand of the undertaking's turnover for each day that the violations continue

iv An article prepared by the Competition Experts of the TCA excellently criticises this situation. Please see "The Determination of the Monetary Fines applied by the Competition Board to Cartels", M. Haluk Ari, H. Goksin Kekevi, Esin Aygun,

v Decision dated 14.10.2005 and No 05-68/958-259. In this decision, the maximum amount of fine imposed on the undertakings party to the cartel in iron-steel sector was only 1,5 per thousand of their turnover, even though this cartel existed for 10 years and caused serious damages.

vi Turk Telekom decision dated 19.11.2008 and No. 08-65/1055-411. In this decision, a monetary fine was imposed on Turk Telekom over its turnover in the relevant product market instead of its total turnover. The decision does not mention the percentage applied for calculation of the fine.

vii The increase and decreases of Basic Fine under the Regulations are described in the Regulations as being on a fractional basis (e.g.1/2 of the Basic Fine) but in this article for ease of reference we state them in percentage terms.

Guner Law Office was established in 1996 and has since grown into one of the major corporate, M&A, banking, litigation, energy and TMT practices in Turkey. Guner Law Office is headed by Ece Guner and works with international law firm Denton Wilde Sapte.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.