- within Accounting and Audit topic(s)

Foreign investors who have suffered losses in the renewable energy sectors in Bulgaria may be entitled to compensation under Bulgaria's numerous bilateral investment treaties ("BITs") and/or the Energy Charter Treaty ("ECT"). In 2009, the European Union ("EU") issued a directive setting the goal that, by 2020, at least 20 percent of the energy consumed in the European Union shall be in the form of renewable energy.1 For Bulgaria, in particular, the target was set at 16 percent.2

In response to the 2020 goals set out by the directive, many European countries, including Bulgaria, passed laws to encourage investment in the renewable energy sector. Some of the incentives included favourable feed-in tariffs ("FiTs")—which paid renewable-power generators above-market rates for their output—and subsidies to consumers who installed renewable energy solutions in their homes. These incentives resulted in a boom in the solar, hydro, and wind sectors, along with an increase in foreign investment funds, in response to promises of generous and long-lasting FiTs.

But as the Bulgarian government began to roll back FiTs, failed to honour other governmental guarantees, and passed laws introducing new fees and taxes on the income of producers of renewable energy, investors in the country's renewable sector have seen, and will continue to see, their investments substantially reduced in value. Although Bulgaria has so far dodged the large number of claims stemming from the changes in renewable energy legislation experienced by Spain and the Czech Republic,3 there are already two pending investor-state arbitration cases against Bulgaria arising out of legislative changes in the renewable energy sector,4 and more are likely to follow.

This Commentary provides an overview of Bulgaria's renewable energy sector and legislation, with an emphasis on how changes in legislation impact investors, and descriptions of the international remedies available to investors seeking to recoup their losses.

Bulgaria's Renewable Energy Sector and Legislation

Despite the fact that renewable energy investment in Bulgaria was virtually nonexistent a decade ago, the nation's renewable energy sector is now second largest among the top 10 emerging markets—having received U.S.$ 5.6 billion in investments between 2009 and 2013.5 By far, the largest amount of investment has gone towards solar energy (U.S.$ 3.2 billion), with the remainder going towards the wind sector.

The sharp increase in investment from 2009 to 2013 can be attributed to Bulgaria's decision to improve its renewable energy sector via laws encouraging investment. In particular, Bulgaria implemented measures for promotion of the use, production, and consumption of energy from renewable sources, such as the introduction of FiTs and the conclusion of long-term power purchase agreements set out in the Law for Renewable and Alternative Energy Sources and Biofuels ("LRAESB").6 The long-term power purchase agreements were 25 years for solar power and 15 years for wind and hydro power. These incentives were not overlooked by international investors from other EU countries as well as the U.S., China, South Korea, and Japan. However, in the face of this boom, the government began taking measures to restrict the available incentives.

Since 2011, therefore, Bulgaria's government, acting through the National Assembly and the Energy and Water Regulatory Commission ("EWRC"), has adopted new laws, policies, and rules that have changed significantly the legal, regulatory, and economic framework within which the renewable energy sector operates. These new laws have indirectly decreased the FiTs and have had significant financial consequences for producers from renewable energy sources ("RES").

The following are the major legal and regulatory changes affecting Bulgaria's renewable energy investors since 2011:

The Law on the Energy for Renewable Resources. On May 3, 2011, Bulgaria adopted the Law on the Energy for Renewable Resources ("LRES"), which replaced the LRAESB and provided for: (i) shorter terms for the power purchase agreements and the application of the FiTs; (ii) late fixing of the FiTs; and (iii) retroactivity for existing developers of the RES projects.

Amendments to Law on the Energy for Renewable Resources. In 2012, the LRES was twice amended: (i) to give the EWRC discretion to determine preferential prices upon performing an analysis of the price-forming elements; and (ii) to introduce connection schedules that changed the already contractually agreed terms for connection by imposing on the producers a new date for connection of their power plants. Further, since 2012, the Electricity System Operator ("ESO") adopted a practice of targeting its powers to curtail energy production against RES producers. Finally, although most of it has been annulled as unlawful by the Supreme Administrative Council, Decision Ц-33/14.09.2012, published on the EWRC website, introduced new, temporary prices for access to the electricity transmission and distribution grids by renewable power plants which, in practice, affected the preferential price.

As a result, while this decision was in force, it caused renewable energy producers to pay millions in charges prior to its annulment. In March 2014, the regulator adopted another decision for determination of access price—Decision Ц-6/13.03.2014—where it provided that the access price would be paid for the access only to the electricity transmission grid and specified a significantly lower price than the temporary access price (2.45 BGN/MWh).

The Electricity Trading Rules. The government continued the legislative changes in 2013 by adopting the Electricity Trading Rules, which required RES producers to participate in the Balancing Market of electricity7 through participation in balancing groups8—combined or special (RES producers were restricted from participating in the standard balancing group). By the time the Balancing Market commenced operations in June 2014, a number of issues had arisen already, including: (i) disproportionate imposition of balancing fees on RES producers; (ii) lack of transparency in the settlement performed by the National Electric Company ("NEK") of the hourly balancing costs for surplus and deficit production and the application of the settlement methodology adopted; (iii) alteration by NEK of the forecasts provided by the coordinators of the special balancing group and the RES producers; (iv) imposition of production curtailments by ESO in the calculation of the imbalances; and (v) NEK's collection of more balancing fees than the actual related cost. In addition, the EWRC approved General Terms for Access to the grid applicable to RES producers that contained detailed provisions permitting the ESO to order producers to curtail production either directly or by ordering the grid operators to do so.

Additional Amendments to Law on the Energy for Renewable Resources. On January 1, 2014, a new amendment to the LERS was introduced which provided for:

(i) a limitation on the quantity of energy purchased at a preferential price. Instead of the entire quantity, only the quantities of electrical energy up to an amount determined by the EWRC could be bought at the determined preferential price and the remainder would be purchased at the price approved by EWRC for electrical energy sold to end suppliers. Thus, an entirely new set of terms and conditions were imposed on existing producers of renewable energy. Their long-term agreements for the purchase of the entire quantity of the produced electricity on preferential prices were modified retroactively; and

(ii) a 20 percent fee on the income of producers of energy from solar and wind power. The fee was deducted by the public supplier, respectively by the end supplier, and paid to the state budget. Although the fee was declared unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Bulgaria in August 2014 on the basis that it was a discriminatory measure and in violation of the effective legislation, according to Bulgarian law a decision of the Constitutional Court does not have retroactive application. Consequently, the amounts that had been paid by RES producers for more than half a year were not reimbursed to them.

Recent Amendments to the Law on the

Energy for Renewable Resources and the Energy

Act. 2015 has seen new amendments to the LERS and the

Energy Act. In July 2015, these amendments were urgently adopted to

ensure additional revenues and potential economies for NEK, and to

provide more flexibility to the EWRC, as follows:

(i) establishment of the "Security of the Electricity System" sum, where five percent of the pre-Value Added Tax monthly incomes from the sale of the produced energy of each of the producers of electricity should be paid as a monthly contribution;

(ii) the purchase price of electricity from RES will be changed when building sites were funded by national or European support schemes. Within six months after the change of the price of long-term contracts for purchase, the producers have to refund to the public provider the difference between the originally determined preferential price and the new price; and

(iii) a new method for determining the hours up to which the produced electricity shall be purchased at the preferential price. Namely, the number of hours can go up to the amount of the net specific production of electricity. In this regard, the National Assembly gave the EWRC until July 31, 2015 to adopt a decision on how to determine the net specific production of electricity for RES producers. In addition, the price for purchase of electricity from RES, which is above the net specific production, will be amended to the price for excess at the Balancing Market. On July 31, 2015, the EWRC adopted Decision SP-1/31.07.2015 setting the levels of net specific production of electricity for almost all of the currently applicable FiTs—189 positions reflecting the types of renewable technologies and preferential prices set throughout the period of 2011-2015. These levels as specified in the decision represent the maximum amount of electricity produced to be purchased under the respective preferential price determined upon conclusion of the respective long-term power purchase agreement. In addition, on the same date, the EWRC adopted another decision introducing a higher mandatory access price only for wind and PV producers (from 2.45 BGN/MWh to 7.14 BGN/MWh).

What are the International Remedies?

These measures, individually and/or in total, have negatively impacted the profitability and value of investments in Bulgaria's renewable energy sector. Accordingly, foreign investors may have recourse to international remedies through investor–state arbitration as provided by the available BITs and/or the ECT.

Investor–state

arbitration is an attractive option. It provides a

specialised and neutral forum within which to bring disputes

against a state. It is often not necessary to exhaust local

remedies or to commence any domestic litigation before bringing an

investor–state arbitration action. However, an investor's

ability to bring a claim will depend generally upon the ownership

structure of the affected investment vehicle.

Some investors will have recourse through BITs. Bulgaria has 59 BITs in force, including, among others, BITs with the Netherlands, Austria, Germany, and the United States.9 Notably, Bulgaria and Italy terminated their BIT on May 9, 2010.10 However, Italian investors that made their investment in Bulgaria prior to the termination date will continue to be covered by the protections of the Bulgaria-Italy BIT for 15 years after the termination date (until May 9, 2025).11

BITs are designed to promote and protect investments by investors of the other state party to the treaty. Most BITs protect a broad range of investments, which encompass all assets. Renewable energy companies typically hold shares in a locally incorporated company that holds rights or licences conferred by law—such investments are likely to be within the protection of investment treaties. Financial institutions that have financed renewable energy investments also can benefit from investment treaty protections as covered investments include loans and claims to money or claims to performance pursuant to a contract having an economic value.

The investor's nationality is typically determined by the place of incorporation and/or the seat of company management in the case of companies and by the domestic law on citizenship in the case of individuals. Many BITs permit investors to make claims for directly or indirectly held investments as well as minority shareholdings. Thus, parent companies or individual shareholders are often able to assert rights relating to an investment held through a subsidiary company. Some also provide that juridical persons incorporated in the host state but controlled by nationals of the other contracting state may be treated as foreign nationals. This provides the investor with options when deciding under which treaty to bring the claim.

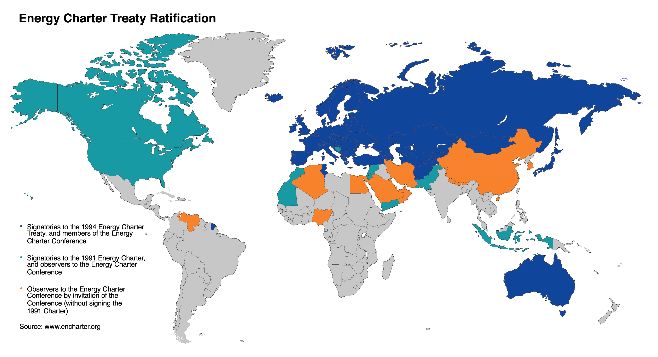

Investors may also have claims under the ECT. The ECT is a multilateral treaty with 52 signatories, of which 49 have ratified it.12 It outlines the principles for cross-border cooperation in the energy industry and provides protection for investors in this sector. Bulgaria, The Netherlands, Austria, and Germany, as well as the EU are contracting parties to the ECT. This provides the option of joining the EU itself to claims against member states, although execution of an award against EU assets may be more difficult to realise.

There are several investment protections available under the ECT. The fair and equitable treatment standard is the most frequently invoked standard in investment disputes and is likely to be the strongest claim in a dispute of the type explained above. The standard is fact-specific and has been breached by: (i) actions or omissions that violate the investor's legitimate expectations relied upon by the investor to make the investment; (ii) conduct that is not transparent or consistent and creates an unstable or unpredictable legal framework or business environment for the investment; (iii) conduct that violates due process or results in a denial of justice; (iv) discriminatory action; (v) interference with a contract; (vi) bad faith; or (vii) harassment or coercion.

The first two iterations of the fair and equitable treatment standard are most likely to be implicated here. The investor's legitimate expectations can be based on the host state's legal framework, contractual undertakings, and any undertakings and representations made explicitly or implicitly by the host state. Changes in the legal framework may be considered breaches if they represented a reversal of assurances made by the host state to the foreign investor.

Investors who have seen their entire investment wiped out, or almost entirely wiped out, also may have recourse to the protection against illegal expropriation. The ECT requires that the expropriation of foreign-owned property must be: (i) for a public purpose; (ii) non-discriminatory; (iii) in accordance with due process; and (iv) accompanied by prompt, adequate and effective compensation equivalent to the fair market value of the expropriated investment before the expropriation became known. A government measure would constitute an expropriation if it effectuated a permanent loss of the economic value of an investment.

There are various other protections under the ECT, which, depending on the circumstances of each individual case, may be invoked. For instance, the ECT guarantees that investments be accorded "most constant protection and security", which can be violated by drastically altering the legal framework for the investments. Another protection provided under the ECT is the legal obligation on a host state not to impair the management, maintenance, use, enjoyment or disposal of investments by "unreasonable or discriminatory measures". The ECT also contains a broadly worded umbrella clause that guarantees the observance of obligations assumed by the host state vis-à-vis the investor or his investment.

There are many advantages to investor–state arbitration. Investors typically seek monetary compensation. In some cases, investors would be entitled only to the amount invested plus costs and expenses. Lost profits will usually be awarded if the investment has a record of profitability or there are other indicia of future profits. Arbitral awards are binding upon the parties and create an obligation to comply with them. Most states comply with awards voluntarily. In the event a party fails to comply with an award, one of the major advantages of arbitration (as opposed to litigation) is the international enforceability of arbitral awards compared with foreign court judgments. It may also be possible to secure third-party funding for the costs of the dispute and/or to bring the claim with a group of similarly affected investors.

While Bulgaria has not lost an investor–state arbitration to date and, therefore, no history as to whether Bulgaria would honour investor–state arbitration awards exists, Bulgaria does not have a known history of non-payment of international awards. Accordingly, there is no reason to believe that Bulgaria would not honour its international obligations.

It is also worth noting that the European Commission ("EC") has sought to intervene in an increasing number of investor–state claims brought by EU nationals against member states. The EC has voiced opposition to intra-EU BITs, i.e., BITs between EU member states. The EU also has disputed the applicability of the ECT to intra-EU disputes. In one case, the EC even issued an injunction barring a member state—Romania—from paying the award in the Micula v. Romania ICSID case13 on the ground that it constitutes illegal state aid under EU law.14 That injunction is likely to remain in place until the EC rules on the ultimate compatibility of that aid with the European single market.15 While the play out of the EC's intervention remains to be seen and can certainly complicate an arbitration, it is by no means a bar to bringing a claim. In 2014, 16 percent of all investor-state arbitrations brought globally were intra-EU in nature.16

This remains a rapidly evolving and contentious area, although there is little doubt that many investors have been severely affected by the proliferation of changes to the renewables sector across Europe. Many have already turned to investor–state arbitration as the most reliable mechanism for recouping their losses.

Footnotes

1 See generally EU Directive on the Promotion of the Use of Energy from Renewable Sources (2009/28/EC, April 23, 2009), available at http://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/eur88009.pdf.

2 Id.

3 In 2013, 23 percent of known investor–state arbitrations arose as a result of government measures regarding renewable energy adopted by Spain and the Czech Republic, and more claims are expected to follow. See UNCTAD, Recent Developments in Investor–State Dispute Settlement, April 2014, at 1.

4 Energo-Pro a.s. v. Republic of Bulgaria, ICSID Case No. ARB/15/19 (under the ECT); EVN AG v. Republic of Bulgaria, ICSID Case No. ARB/13/17 (under the Austria-Bulgaria BIT and the ECT).

5 The PEW Charitable Trusts, Power Shifts: Emerging Clean Energy Markets, May 2015, at 22.

6 Law for Renewable and Alternative Energy Sources and Biofuels, prom. SG. 49/19 June 2007 ("LRAESB").

7 Pursuant to the Energy Act (prom. SG. 107/9 Dec. 2003), "Balancing Energy Market" is an organized trade in electricity for the purpose of maintaining the balance between production and consumption in the electric power system.

8 Pursuant to the Energy Act (prom. SG. 107/9 Dec. 2003), "Balancing Group" is a group composed of one or more electricity traders, users or owners of the networks organized according to the requirements of the Electricity Trading Rules.

9 See UNCTAD, Investment Policy Hub, available at http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA/CountryBits/30#iiaInnerMenu.

10 UNCTAD, Investment Policy Hub, available at http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/IIA/country/30/treaty/682.

11 Bulgaria-Italy BIT, Art. 15.2 ("Per gli investimenti effettuati precedentemente alla data della scadenza del presente Accordo le disposizioni degli articoli da 1 a 14 rimarranno in vigore per ulteriori 15 anni a partire dalla data della scadenza del presente Accordo" [unofficial translation: "For investments made prior to the date of termination of this Agreement, Articles 1 to 14 shall remain in force for 15 years from the date of termination of this Agreement"]), available at http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/Download/TreatyFile/536.

12 Contracting Parties to the Energy Charter Treaty as of August 2015, available at http://www.energycharter.org/process/energy-charter-treaty-1994/energy-charter-treaty/ (Afghanistan, Albania, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, European Union and Euratom, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Moldova, Mongolia, The Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tajikistan, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and Uzbekistan).

13 Ioan Micula, Viorel Micula, S.C. European Food S.A, S.C. Starmill S.R.L. and S.C. Multipack S.R.L. v. Romania, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/20, Final Award dated 11 Dec. 2013.

14 See Luke Eric Peterson, European Commission Enjoins Romania from Paying ICSID Award, Thus Throwing a Wrench into Enforcement of Intra-EU BIT Ruling, IAReporter, 7 Aug. 2014, available at www.iareporter.com.

15 Id.

16 See UNCTAD, IIA Issues Note: Recent Trends in IIAS and ISDS, Feb. 2015, at 6.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]