INTRODUCTION

As a demonstration of India's combined political will, the much awaited and debated Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (Code) was passed by the Upper House of the Parliament on 11 May 2016 (shortly after being passed by the Lower House on 5 May 2016). The Code has been enacted at a very critical time for the Indian economy when the domestic banking industry is struggling to cope with a welter of bad loans and eagerly looking for a legal framework to manage stress situations in a time bound and efficacious manner. The Code is aimed at addressing the concerns of both domestic and foreign creditors by creating a level playing field, and ensuring greater certainty around the bankruptcy process. This is expected to encourage cross border financing and unsecured lending to local borrowers, thereby reducing the pressure on credit institutions in India.

Once the Code receives the assent of the President of India and is notified, the country will have a new legal regime that primarily enables time-bound restructuring and bankruptcy of debtors. As such, the Code is a landmark piece of legislation establishing a robust legal framework which brings about a much overdue reform that is aimed at creating necessary procedures for swift resolution of insolvency and bankruptcy in India. It attempts at bringing the Indian statutory regime at par with some of the most legally advanced jurisdictions of the world.

OBJECTIVES

Some of the primary objectives with which the Code has been conceptualized are:

- to consolidate the laws relating to insolvency, reorganization and liquidation/ bankruptcy of all persons, including companies, individuals, partnership firms and Limited Liability Partnerships (LLPs) under one statutory umbrella and amending relevant laws;

- time bound resolution of defaults and seamless implementation of liquidation/ bankruptcy and maximizing asset value;

- to encourage resolution as means of first resort for recovery;

- creating infrastructure which can eradicate inefficiencies involved in bankruptcy process by introducing National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT), Insolvency Resolution Professional Agencies (IPAs), Insolvency Professionals (IPs) and Information Utilities (IUs).

SALIENT FEATURES

1. Unified Legislation

The Code is a comprehensive piece of legislation addressing insolvency/ bankruptcy issues pertaining not just to companies, LLPs (and other limited liability entities); but also to individuals and partnerships. The Code also attempts to streamline the multifarious legislations which are currently in operation in India in this area and bring all relevant provisions under one common umbrella. In order to cover bankruptcy of individuals, the Code will repeal the Presidency Towns Insolvency Act, 1909 and Provincial Insolvency Act, 1920. Additionally, the Code will amend 11 statutes including, inter alia, the Companies Act, 2013 (Companies Act) Sick Industrial Companies (Special Provisions) Repeal Act, 2003 (SICA), Limited Liability Partnership Act, 2008 (LLP Act), Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act, 2002 (SARFAESI) and Recovery of Debts Due to Banks and Financial Institutions Act, 1993 (RDDBFI).

2. Code Mandated Infrastructure

- Insolvency

Regulator

The Code seeks to establish an Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (Board) which will function as the regulator for all matters pertaining to insolvency and bankruptcy. The Board will exercise a range of legislative, administrative and quasi-judicial functions. Some of the primary functions of the Board will include regulating entry, registration and exit of IPAs, IPs and IUs in the field of insolvency resolution, setting out eligibility requirements for such entities, making model bye laws for IPAs, setting out regulatory standards for IPs, specifying the manner in which IUs can collect and store data, and generally acting as the regulator overseeing the resolution process in the manner specified under the Code. - Insolvency Adjudicating

Authority

The Code specifies 2 different adjudicating authorities (the Adjudicating Authority) which will exercise judicial control over the insolvency process as well as the liquidation process.

In case of companies, LLPs and other limited liability entities (which may be specified by the Central Government from time to time), the NCLT shall be acting as the Adjudicating Authority. All appeals from NCLT shall lie with the appellate authority, i.e. the National Company Law Appellate Tribunal (NCLAT).

In case of individuals and partnerships, the Adjudicating Authority would be the Debt Recovery Tribunal (DRT) with the Debt Recovery Appellate Tribunal (DRAT) continuing to be the appellate tribunal even for insolvency/ bankruptcy matters. The Supreme Court of India shall have appellate jurisdiction over NCLAT and DRAT. - Insolvency

Professionals

Under the Code, IPs will be the licensed quasi-administrators who will carry out on ground supervision of resolution process, manage affairs and assets of the debtor during the process, receive and finalise resolution plans with the committee of creditors (COCs) and carry out the liquidation/bankruptcy of the debtor if the trigger for liquidation/bankruptcy (as set out below) gets activated. - Insolvency Professional

Agencies

The IPAs will admit IPs, prepare model of code of conduct, establish performance standards for IPs, redress customer grievances against the IPs and act as a disciplinary body for all IPs registered with them. - Information

Utilities

One of the dilatory factors plaguing the existing winding up proceedings has been the time taken by the courts in deciding whether a debt exists or not. In order to address this issue in an objective way, the Code seeks to put in place a robust infrastructure of IUs with an aim to have such information readily available for an Adjudicating Authority to rely upon. IUs are expected to collect, classify, store and distribute all possible relevant data pertaining to the debtors to/from companies and financial and operational creditors of a debtor, including but not limited to the data on financial defaults. However, the specific nature of data required to be managed by IUs will be clarified only when the rules under the Code will be notified.

3. Corporate Insolvency

- Meaning and

Scope

Part I of the Code deals with corporate insolvency mechanism pertaining to limited liability entities including companies, LLPs and other limited liability entities (Corporate Insolvency) as may be notified from time to time; but does not include any financial service provider. Corporate Insolvency includes two processes within its ambit, (i) Insolvency Resolution and (ii) Liquidation. - Strict

Timelines

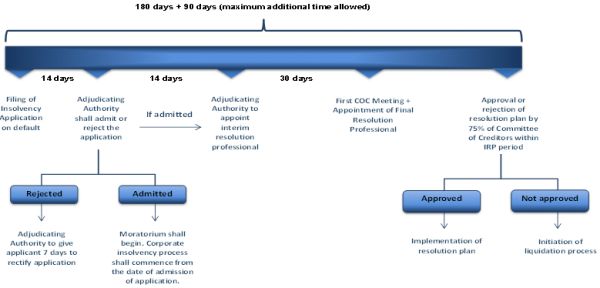

The Code prescribes a timeline of 180 days for the insolvency resolution process, which begins from the date the application is admitted by the NCLT. The period is subject to a single extension of 90 days in the event the Adjudicating Authority (being petitioned by a resolution passed by a vote of 75% of the COC) is satisfied that the corporate insolvency resolution process cannot be completed within the period of 180 days. This time period is also applicable to individual insolvency resolution process.

During this period, the creditors and the debtor will be expected to negotiate and finalise a resolution plan (accepted by 75% of the financial creditors) and in the event they fail, the debtor is placed in liquidation and the moratorium lifted. - Triggers for Insolvency

Resolution Process (IRP)

In order to achieve quick resolution of distress, the Code prescribes certain 'early detection' triggers which can be activated on first signs of stress. The moment a default occurs, a financial creditor, an operational creditor or a corporate applicant may approach the Adjudicating Authority (i.e. NCLT) with an application for initiation of IRP. The procedure for these 3 group of applicants under the Code varies and are primarily as follows:

- Financial Creditors: Financial creditors are those who extend financial debt to a corporate debtor or to whom a financial debt is assigned by a financial creditor. In case of a financial creditor, the moment a financial default occurs, the financial creditor can make an application to the NCLT for initiating IRP. The financial creditor for this purpose has to submit records of default with IU or evidence of such default in case the information is not available with IU.

- Operational Creditors: These are creditors to whom corporate debtor owes operational debt (including claims for goods and services, employment or dues to any government under any law) or to whom such debt is assigned by an operational creditor. The operational creditor may upon occurrence of a default on operational credit, serve a demand notice or invoice demanding payment on the corporate debtor. If the corporate debtor fails to make such payment within 10 (ten) days or fails to notify operational creditor of a dispute in relation to the requested payment, the operational creditor can make an application to NCLT along with demand notice/invoice and other documents as prescribed therein.

- Corporate Applicant: A Corporate applicant includes the corporate debtor (whose IRP is proposed to be initiated) or its shareholder, management personnel or employees satisfying certain criteria. A corporate applicant may file an application for IRP upon occurrence of any default and shall along with application submit its books of account and other documents to initiate the IRP.

- Transfer of Powers and

Moratorium

The Code stipulates a statutory moratorium during the limited IRP period whereby no suits, proceedings, recovery or enforcement action may take place against the corporate debtor. However, the IP will be appointed as the resolution professional in terms of the procedure outlined in the Code, who will take over the management and powers of board of directors of the corporate debtor. All officers and managers of the corporate debtor are required to act on instructions of the IP and all accounts of the corporate debtor will be managed by it. - Committee of Creditors to

chart the course during IRP

The COC shall only include financial creditors as decision makers (operational creditors with more than 10% aggregate exposure have mere observer status during the COC meetings) and shall be responsible for deciding the important affairs of the company. It shall also be responsible for authorising the IP (acting as resolution professional) to take (or not to take) certain actions such as raising interim finance upto the limit specified by the committee, creating security on assets of the secured creditor, undertaking related party transactions, amending constitutional documents, change of capital structure or management of the Borrower etc. More importantly, the COC shall approve the resolution plans received by the IP. All decisions of the COC are required to be approved by a majority of 75% of the voting shares/value of the financial creditors. - Liquidation

In the event that:

- the COC cannot agree on a workable resolution plan within the IRP Period (i.e. 180 days extendable once by another 90 days);

- the COC decides to liquidate the company;

- the NCLT rejects the resolution plan; or

- the corporate debtor contravenes provisions of the resolution plan,

- pass an order requiring liquidation of corporate debtor;

- make a public announcement of corporate debtor entering liquidation; and

- require a liquidation order to be sent to the registering authority of the corporate debtor (for example Registrar of Companies in case of companies incorporated under Companies Act).

- Waterfall

In case of liquidation, the assets of the corporate debtor will be sold and the proceeds will be distributed amongst the creditors in the following order of priority:

- cost of the insolvency resolution process and liquidation;

- secured creditors (who choose to relinquish their security enforcement rights and workmen's dues relating to a period of 24 months preceding the liquidation commencement date);

- wages and unpaid dues of employees (other than workmen) for a period of 12 months preceding the liquidation commencement date;

- financial debts owed to unsecured creditors;

- statutory dues to be received on account of Consolidated Fund of India or Consolidated Fund of a State (relating to a period of whole or part of 2 years preceding the liquidation commencement date) and debts of secured creditors (remaining unpaid after enforcement of security);

- remaining debts and dues;

- dues of preference shareholders; and

- dues of equity shareholders or partners (as may be applicable).

TIME BOUND INSOLVENCY RESOLUTION PROCESS

4. Individual Bankruptcy

- Scope and

Threshold

Part III of the Code sets out the legal regime dealing with the insolvency mechanism for individuals and partnership firms and includes within its ambit, 3 processes, namely, the 'fresh start process', 'the insolvency resolution process' and 'bankruptcy'.

The threshold for applicability of Part III of the Code to individuals and partnership firms have been set at a minimum of INR 1,000. However, the Central Government may by notification increase the threshold to a minimum of INR 1,00,000. - Fresh Start

Process

An application for a fresh start process, can be made for any debt (other than secured debt, debt which has been incurred 3 months prior to the date of application for fresh start process and any 'excluded debt').

The Code has introduced the concept of 'excluded debt' and 'excluded assets' for individuals and partnership firms under which certain debt and assets of the debtor would be exempted from the purview of fresh start process and the insolvency process under the Code. For example, any liability imposed by a court/tribunal, any maintenance required to be paid under any law and any student loan form a part of 'excluded debt'. Similarly, any unencumbered tools, books or vehicles of the debtor which are required for personal use, employment or vocation, unencumbered life insurance policies, pension plans, personal ornaments having religious sentiments and single dwelling unit of the debtor fall within the ambit of 'excluded assets'.

- Eligibility

criteria

The Code provides for stringent criteria for any debtor to be eligible to apply for a fresh start process under the Code. For example, any person who does not own a dwelling unit and has a gross annual income of less than INR 60,000, with assets of a value not exceeding INR 20,000, and the aggregate value of the qualifying debt of such individual or partnership firm not exceeding INR 35,000 shall be eligible to apply for a fresh start process. In addition, it is imperative that such applicant is not an undischarged bankrupt and there are no previous fresh start process or insolvency resolution process subsisting against him. - Moratorium

The Code stipulates an interim-moratorium period which would commence after filing of the application for a fresh start process and shall cease to exist after elapse of a period of 180 days from the date of application. During such period, all legal proceedings against such debtor should be stayed and no fresh suits, proceedings, recovery or enforcement action may be initiated against such debtor.

However, the Code has also imposed certain restrictions on the debtor during the moratorium period such as the debtor shall be not be permitted to act as a director of any company (directly/indirectly) or be involved in the promotion or management of a company during the moratorium period. Further, he shall not dispose of his assets or travel abroad during this period, except with the permission of the Adjudicating Authority.

- Eligibility

criteria

- Insolvency Resolution

Process

An application to initiate an IRP under the Code can be either made by the debtor (personally or through an insolvency resolution professional) or by a creditor (either personally or jointly with other creditors through an insolvency resolution professional).

However, a partner of a partnership firm is not eligible to apply for an IRP unless a joint application is filed by majority of the partners of the partnership firm.

- Repayment Plan

In the IRP, the creditors and the debtor need to arrive at an agreeable repayment plan for restructuring the debts and affairs of the debtor, supervised by an IP. The repayment plan will require approval of a three-fourth majority of financial creditors in value.

The repayment plan may authorize or require the resolution professional to: (a) carry on the debtor's business or trade on his behalf or in his name; or (b) realize the assets of the debtor; or (c) administer or dispose of any funds of the debtor. - Moratorium

The Code prescribes a timeline of 180 days within which the Adjudicating Authority shall pass an order on the repayment plan and beyond such period, if no repayment plan has been passed by the Adjudicating Authority, the moratorium in respect of the debts under consideration under the IRP shall cease to have an effect.

- Repayment Plan

- Bankruptcy

The bankruptcy of an individual can be initiated by the debtor, the creditors (either jointly or individually) or by any partner of a partnership firm (where the debtor is a firm), only after the failure of the IRP or non-implementation of repayment plan. The bankruptcy trustee is responsible for administration of the estate of the bankrupt and for distribution of the proceeds on the basis of the priority set out in the Code.

5. Key Changes in the Insolvency/Liquidation Regime

- Decision Making in the Hands

of Creditors

Presently, winding up of companies as envisaged in the Companies Act vests the decision on whether a company should be wound up or not on the wisdom of the High Court/NCLT. On the other hand, under the new regime, if the restructuring fails to be implemented as prescribed under the Code it would lead to automatic liquidation of the debtor (except in case of individuals). - Unsecured Creditors Vote at

Par

Under the Code, each financial creditor of the COC, whether secured or not, gets to vote on the resolution plan of the corporate debtor on the basis of its voting share (proportionate to the money advanced by the creditor). - Government Dues Take

Backseat

Under the Code, government dues including taxes rank lower than the unsecured creditors and wages as against the exiting regime, where after secured creditors and workmen dues, government dues including all taxes take preference on liquidation payouts. - Individual bankruptcy gets a

shot in the arm

Currently, individual bankruptcy proceedings are adjudicated upon by district courts under 2 different statues. The Code proposes to unify the regime governing individual bankruptcy and in case where the individual bankruptcy is initiated alongside the corporate insolvency, NCLT will have jurisdiction to hear the matter relating to individual bankruptcy along with corporate insolvency. This is expected to speed up resolution on such matters. - Protection to

workers

The Code protects the workers in case of insolvency, paying their salaries for up to 24 months in priority over all other creditors including secured creditors. This is a welcome change as in most cases of corporate insolvency, the workers and employees end up bearing the brunt of long drawn insolvency/bankruptcy process. - Incentive to Insolvency

Professionals

In the distribution of liquidation proceeds, the cost of IP and the IRP has first priority, thereby acting as an incentive for them to strive for speedy resolution. This is at par with international practices. - Interim

Financing

The Code prescribes that any interim financing and the cost of raising such financing will be included as part of the IRP cost, thereby giving it first priority in the waterfall and also in any creditor driven plan. Security can be created over the assets of the company to secure such financing by the interim resolution professional without the consent of existing creditor(s) if the value of the property secured in favour of existing secured creditors is at least twice the outstanding debt. However, any financing after the appointment of the resolution professional and constitution of the COC must be approved by 75% of the financial creditors by value. - Cross Border

Insolvency

The Code for the first time attempts to addresses the issue of cross border insolvency given the multi-jurisdictional spread of assets of large corporates. In order to deal with this aspect, the Code stipulates a two pronged solution, one being the Central Government entering into agreements with other countries for enforcing the provisions of the Code and the other giving the Adjudicating Authority the authority to write a letter to the courts and/or authorities of other countries (as may be relevant) for seeking information or requesting action in relation to the assets of the debtor situated outside India.

6. Road Ahead

- Operational

Issues

- Infrastructure Requirements: The Code proposes the establishment of the Board and NCLT, which if the government is able to set up even within a year will be laudable, considering the manpower/ facilities these institutions will require to perform their respective functions and the expertise and training they will need to do justice to the aims of the Code.

- Quality Professionals: Successful implementation of the Code will require a huge force of trained and skilled insolvency professionals. A strong focus and a well-defined plan will be needed to develop a large pool of insolvency professionals and an institutional structure which will produce, certify and regulate them. Such insolvency professionals will not only need to understand the nuances of restructuring/ liquidation but must also be capable of carrying out the affairs of the company during the process. This process will definitely take a substantial amount of time, resources and expertise. Moreover, effort will be needed to ensure that such professionals are available across the entire country and not just for high profile cases in financial hubs.

- Information Systems: The underlying assumption for the success of the Code is to have access to quality information. For this to materialize, robust utilities with state of the art technologies will swiftly need to be put in operation.

- Adjudication Infrastructure: By

December 2015, almost 59,000 cases were pending before DRTs, which

currently deal with recovery cases of only banks and certain

financial institutions. This is despite a strict statutory

prescription of 180 days for resolution of disputes in relation to

recovery of debt. The major reason for clogging of pending cases is

the multiplicity of proceedings and misuse of the remedy of appeal

to DRAT and other forums. The Code does not take away this option

and the order of the DRT and NCLT may be further challenged with

DRAT and NCLAT, respectively. The appellate order may also be

further challenged at the Supreme Court. Therefore, while the

intent objective behind the Code is laudable, the sheer enormity of

disputes/appeals in the country and the lack of infrastructure to

support this legislative intent, will be a key challenge which will

need to be overcome in order to achieve the intended speed.

In addition, the already over-burdened DRTs are now being assigned with the additional responsibility of adjudicating insolvency/ bankruptcy cases of individuals (which can be initiated by all creditors or the individuals themselves). A major overhaul of DRT infrastructure both in terms of physical facilities and manpower will be needed to achieve what the Code seeks. - Role of the Board: Instead of making the IPs and/or IPAs self-regulated, the Board has been assigned with the responsibility of regulating their performance and laying down the standards of performance. In most insolvency/ liquidation proceedings, government will be an interested party for recovery of the unpaid statutory dues of its several departments. This will make the impartial operation of insolvency professionals (whose entry and exit in the insolvency profession is regulated by the government through the Board) difficult. As such, for achieving the objectives of the Code and ensuring good governance of the IPs and/or IPAs, the minimum standards set by the Board should be further strengthened in practice with self-regulation.

- Legal

Considerations

- Code yet to be effective: The Bill will become a statute upon receiving the Presidential assent. However, the Act provides that the provisions of the Act will come into effect on the date appointed by Central Government and notified in this behalf. Looking at the infrastructural requirements of the Act, it may be even possible that similar to the Companies Act, different provisions of the Bill are notified on different dates, as and when the corresponding infrastructure is implemented. In other words, before the Code is fully operational, we are likely to see a lot of teething issues which will need to be addressed.

- Interplay of Existing Laws: As outlined earlier in this note, the Code not only repeals 2 statutes, but also amends 11 other statutes such as Companies Act, SICA and SARFAESI for effectuating the provisions relating to insolvency and liquidation/ bankruptcy of all legal and natural persons under the Act. However, the interplay of provisions of the Code, the amended statutes and several other statutes (such as Negotiable Instruments Act, 1881) will be an important factor in determination of insolvency proceedings. It is imperative that the provisions of all the key legislations are synchronized in order to ensure that there are no discrepancies or overlaps with existing laws. Failure to ensure this may lead to more confusion in the short run, as far as applicability of specific laws is concerned.

- Cross Border Insolvency: Even though the Code suggests 2 mechanisms to deal with the cross border element of insolvency/liquidation, a comprehensive framework needs to be imbibed to effectively deal with this issue. Various Indian companies have assets and creditors located across different parts of the world and various foreign companies have subsidiaries in India. Issues relating to Insolvency/liquidation of Indian companies with assets located in several jurisdictions outside India and vice-versa cannot be achieved without having a mechanism like adoption of the UNCITRAL Model Law on Cross Border Insolvency. In case of bilateral agreements suggested by the Code presently, it will not only be difficult but will also take a very long time to negotiate an agreement with each country. In addition, several countries may refuse to divulge any information about the assets located in their country upon receipt of a letter envisaged under the Code. As such, while the Code recognises cross border issues, it does not specifically deal with them other than providing the legal basis for dealing with the issue down the line.

- Practical

Ramifications

- Paradigm shift in approach to debt: The Code will fundamentally change the approach to debt in India across a cross-section of society, including the approach and psychology of promoters towards lenders, the way business is done and for individuals, who will all need to adapt to the new framework.

- Balancing Interests of Different Creditors: In any restructuring process, different creditors have varying interests which often leads to conflicts. Depending upon the nature of their debt (operational or financial) or the security of debt (secured or unsecured), each creditor may have a different strategy of recovery. Likewise, foreign creditors may have a different approach from domestic creditors. The new inter-creditor dynamics introduced by the Code will realign the existing practices of various creditor groups.

- Delaying Tactics: One of the key objectives of the Code is to have a system which curbs tactics used by debtors to delay enforcement/winding up/restructuring by 'gaming' the system. This is often done by restricting dissemination of correct information to the lenders and filing of frivolous appeals against the orders passed in favor of the lenders. While the Code addresses the underlying causes for such delaying tactics and seeks to put robust information systems in place, it is yet to be seen if this is sufficient in practice to prevent debtors from arm-twisting the lenders who may not see sufficient recovery from the liquidation process.

- Time bound process and restrained role of the Courts: The Code seeks to implement a time bound restructuring of the debtor while encouraging a limited the involvement of Adjudicating Authorities and other judicial remedies. No doubt the ability of Adjudicating Authorities and courts to exercise this restraint will be tested by corporate debtors.

- Third Parties Stepping-in: Based on the processes contemplated by the Code, a concern arises as to how well equipped would third party professionals and creditors directing them be, to step into the shoes of the promoters and take control of the board, especially at the beginning of the insolvency process, and run the underlying business of a defaulting debtor.

- Applicability: Unlike bankruptcy laws in the US, the Code does not envisage 'debtor in possession' (DIP) financing, which would effectively allow the debtor to keep control of the assets during the IRP. Rather, it follows a UK style approach where the IP controls the process during the IRP. However, in the Indian context, the Code does not allow the IP to sell assets without creditor consent, thereby making UK style administration sales or pre-packaged sales ('pre-packs') difficult to achieve.

Comment

The Code is a landmark piece of legislation providing a major facelift to the existing regime relating to restructuring and insolvency and bankruptcy in India. It promises to provide the one big missing piece in the existing jigsaw of laws in the form of establishing a framework for time–bound resolution for delinquent debts. India now has a bankruptcy and insolvency framework which is comparable with international standards and while this will go a long way in bringing an element of certainty and predictability to commercial transactions in the country and facilitating the ease of doing business, the litmus test for its success will be in how it is implemented. In particular, various practical, logistical and legal hurdles will need to be overcome and the coming months will be crucial with a lot resting on the nuts and bolts of the rules which are now expected to be notified under the Code.

The content of this document do not necessarily reflect the views/position of Khaitan & Co but remain solely those of the author(s). For any further queries or follow up please contact Khaitan & Co at legalalerts@khaitanco.com