Introduction

United States trademark law provides for the protection of "trade dress"—the overall image and appearance of a product and its packaging. Trade dress "involves the total image of a product and may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, graphics, or even particular sales techniques."1 To be protectable, trade dress must be both distinctive and nonfunctional.2

Nonfunctionality comes in two forms: utilitarian and aesthetic functionality. Recently, a pair of appellate courts issued decisions shedding light on these potent tools for invalidating asserted trade dress: Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v. Lotte Int'l Am. Corp., 977 F.3d 261, 264 (3d Cir. 2020) (involving utilitarian functionality) and LTTB LLC v. Redbubble, Inc., 840 F. App'x 148, 149 (9th Cir. 2021) (involving aesthetic functionality). This paper discusses those case and the doctrines they elucidate.

What is utilitarian functionality? Why and when does it bar protection?

Trade dress is considered functional if it (1) is essential to the use or purpose of a device or product, or (2) affects the cost or quality of the device or product.3 Put differently: "something is 'functional' if it works better in this shape."4 In determining whether a trade dress is functional, courts often consider four factors set forth in In re Morton-Norwich Products, Inc.:5

1. the existence of a utility patent disclosing the utilitarian advantages of the design;

2. the existence of advertising or promotional materials in which the originator of the design touts the design's utilitarian advantages;

3. the availability to competitors of functionally equivalent designs; and

4. whether or not the design results from a comparatively simple, cheap, or superior method of manufacturing the device.6

Functionality is a powerful doctrine because once it is proven by the party challenging the feature or mark at issue, it outweighs any evidence of secondary meaning or actual confusion that the other side presents.7 If found functional, a feature or design is not protectable under any circumstance, and the existence of alternative designs capable of performing the same function is irrelevant.8 As such, functionality is often dispositive in trade dress disputes.

The functionality doctrine emerged as a way to confine the protection of utility and functional designs to the exclusive domain of patent law.9 Functionality also plays an important role in promoting free competition by allowing competitors to copy useful, functional features that are deemed necessary to compete effectively.10 The theory behind the doctrine was well articulated by the Supreme Court as follows:

The functionality doctrine prevents trademark law, which seeks to promote competition by protecting a firm's reputation, from instead inhibiting legitimate competition by allowing a producer to control a useful product feature. It is the province of patent law, not trademark law, to encourage invention by granting inventors a monopoly over new product designs or functions for a limited time, 35 U. S. C. §§154, 173, after which competitors are free to use the innovation. If a product's functional features could be used as trademarks, however, a monopoly over such features could be obtained without regard to whether they qualify as patents and could be extended forever (because trademarks may be renewed in perpetuity).

Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. at 164-65 (1995).

In 1998, Congress amended the Lanham Act to make functionality (1) a ground for ex parte rejection, (2) a ground for opposition of an application and cancellation of a registration, and (3) a statutory defense to (i.e., a way to challenge) an incontestably registered mark.11 Moreover, Section 43(a)(3) of the Lanham Act provides that: "In a civil action for trade dress infringement under this Act for trade dress not registered on the principal register, the person who asserts the trade dress protection has the burden of proving that the matter sought to be protected is not functional."12 If a mark has been registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, it is presumed to be non-functional; although not impervious to challenge.13

The "Pocky" Case: Useful (Not Essential) Cookie Sticks are Functional

They say imitation is the highest form of flattery, but for Ezaki Glico, the company behind the famous and beloved chocolate-covered cookie stick, Pocky, competitor imitation is a constant source of frustration. One competitor in particular, Lotte, sells its Pepero cookie, which, like Pocky, is stick-shaped and partly coated in chocolate or flavored cream.

In 2015, Ezaki Glico sued Lotte in the District Court for the District of New Jersey alleging trademark infringement and unfair competition in violation of the Lanham Act and the New Jersey Fair Trade Act.14 The District Court granted summary judgment for Lotte after finding Pocky's trade dress configuration is functional and therefore not protectable.15 Ezaki Glico appealed to the Third Circuit.

On appeal, the Third Circuit noted that both the Lanham Act and New Jersey Fair Trade Act claims depend on the validity of the Pocky trade dress and focused its analysis on whether or not the trade dress is functional.16 The court noted that because copying is a legal part of market competition, "even if copying would confuse consumers about a product's source, competitors may copy unpatented functional designs."17

Unsurprisingly, Ezaki Glico urged the court to adopt a narrow interpretation of what it means for a trade dress to be functional and argued that the term should be equated with what is "essential."18 But the court looked to the term's ordinary meaning and determined that a product's configuration is functional when it is useful.19 In so doing, the court looked to dictionary definitions; the Supreme Court decisions in Qualitex, TrafFix, and Wal-Mart; and the Lanham Act's relationship to the Patent Act.20 On the latter point, the Third Circuit reasoned that trade dress, like trademark law more broadly, is designed to protect the owner's goodwill and to prevent consumer confusion from occurring—not to defend against the copying of an original work (copyright law) or an invention (patent law).21

Against this backdrop, the court turned its attention to whether or not functionality had been proven, noting the several ways in which this can be done. The court's non-exhaustive list of considerations included evidence directly showing "that a feature or design makes a product work better," the recognition and praise of a feature's usefulness by the product's marketer, a utility patent on the feature, and the limited ways to design a product.22

Addressing each consideration in turn, the court first determined that "every feature of Pocky's registration relates to the practical functions of holding, eating, sharing, or packing the snack."23 Specifically, it noted that the uncoated handle of each stick allows people to eat it without getting their hands dirty, and the shape of the stick itself makes the cookie easy to hold, eat, and share.24 Second, the court stated that Ezaki Glico promotes the design through advertisements, which tout its useful features and state "Pocky lends itself to sharing anytime, anywhere, and with anyone."25 Third, the court found Ezaki Glico's utility patent irrelevant to the functionality analysis of the trade dress features as none of the claimed features in the manufacturing method overlapped with its trade dress.26 Thus, any consideration of the utility patent by the district court was in error, though immaterial. Finally, even though there were alternative cookie designs available to Lotte, the court determined there was ample evidence that the product design was functional.27

In conclusion, recognizing the separate domains of patents and trademarks, the court held that Ezaki Glico could not rely on its (now invalid) trade dress to prevent competitors from using the functional features of the cookie and affirmed the district court's decision, aptly stating, "That's the way the cookie crumbles."28

What is aesthetic functionality? Why and when does it bar protection?

The doctrine of aesthetic functionality has its roots in a comment in the 1938 Restatement of Torts: "When goods are bought largely for their aesthetic value, their features may be functional because they definitely contribute to that value and thus aid the performance of an object for which the goods are intended."29 The doctrine has since evolved to deny trademark protection to design features that make a product more aesthetically pleasing or commercially desirable, serve no source-identifying function, and are necessary for competition. For example, in Brunswick Corp. v. British Seagull Ltd., the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit held that the color black on outboard motors created a "competitive need" because it had the visual effect of decreasing the apparent size of the motor and because it was color-compatible with many different boat color schemes. Brunswick Corp. v. British Seagull Ltd., 35 F.2d 1527 (Fed. Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1050 (1995).30 Aesthetic functionality has also been used, in certain circumstances, to foreclose liability for infringement for uses of designs that are merely aesthetically functional and not source identifying.31

One must exercise caution when applying the aesthetic functionality test. As Professor McCarthy notes: "if read literally, this test would wipe out the law of trademarks. If not read literally, then by what criteria does one confine it to some lesser scope?"32 Some visually pleasing patterns may increase a product's value by identifying its source.33 Consider, for example, the characteristic pattern of a famous handbag manufacturer. While the pattern does not render the bag more portable or useful, it makes the bag more desirable because of its source, allowing the brand owner to charge a premium as a result.34 If, on the other hand, a pattern merely makes a bag look good, telling the user nothing about who makes the product, it could very well be deemed aesthetically functional if there's a competitive need to use the pattern.35

In one of the first cases to discuss aesthetic functionality—Pagliero v. Wallace China Co., 198 F.2d 339 (9th Cir. 1952)—the plaintiff sought to enjoin the defendant from making china that copied the floral pattern featured on the plaintiff's china. The court held that the plaintiff could not assert trademark rights in its floral pattern on the ground that it was functional.36 Driven by its findings that the plaintiff's design was an "essential" selling feature for its china, the Court explained:

One of the essential selling features of hotel china, if, indeed, not the primary, is the design. The attractiveness and eye-appeal of the design sells the china. Moreover, from the standpoint of the purchaser china satisfies a demand for the aesthetic as well as for the utilitarian, and the design on china is, at least in part, the response to such demand.

Pagliero, 198 F.2d at 343-44.

Because consumers purchased the china for its floral pattern, and because they perceived that pattern as an attractive feature rather than an indicator of source, the court found the design necessary for competition and unprotectable as a trademark.37 The Pagliero court noted, however, that in cases "where the feature or, more aptly, design, is a mere arbitrary embellishment, a form of dress for the goods primarily adopted for purposes of identification and individuality and, hence, unrelated to basic consumer demands in connection with the product, imitation may be forbidden."38

Pagliero must be viewed with caution, as it has been questioned, criticized, and limited by numerous commentators and courts. See, e.g., Animal Fair, Inc. v. Amfesco Indus., 794 F.2d 678 (8th Cir. 1986); see also Ferrari S.P.A. v. Roberts, 944 F.2d 1235, 1246-47 (6th Cir. 1991); In re DC Comics, Inc., 689 F.2d 1042, 1053 (C.C.P.A. 1982) (Nies, J., concurring) ("No principle of trademark law requires imposition of penalties for originality, creativeness, attractiveness, or uniqueness of one's product"); Keene Corp. v. Paraflex Indus., Inc., 653 F.2d 822 (3d Cir. 1981) (noting that if the Pagliero formulation were the law, then the absurd result would be that "the more appealing the design, the less protection it would receive."); 1 McCarthy, § 7:80.

Indeed, the Ninth Circuit, home of Pagliero, has itself seemingly retreated from the broad position taken in that case. For example, in one case, it reversed a district court's dismissal against an imitation of the Louis Vuitton repeating "LV" and floral symbol covering the surface of luggage and handbags, explaining:

We disagree with the district court insofar as it found that any feature of a product which contributes to the consumer appeal and saleability of the product is, as a matter of law, a functional element of that product. Neither Pagliero nor the cases since decided in accordance with it impel such a conclusion.

Vuitton, 644 F.2d at 769.

Later, a district court in the Ninth Circuit observed that "the aesthetic functionality is essentially defunct in this circuit."39 This year, however, the Ninth Circuit spoke again on aesthetic functionality. This time, the court breathed new life into the doctrine by finding that a plaintiff's mark, tantamount to a pun, was aesthetically functional and non-protectable.

Pun Intended, but Not Infringing: Ninth Circuit Finds LETTUCE TURNIP THE BEET Aesthetically Functional

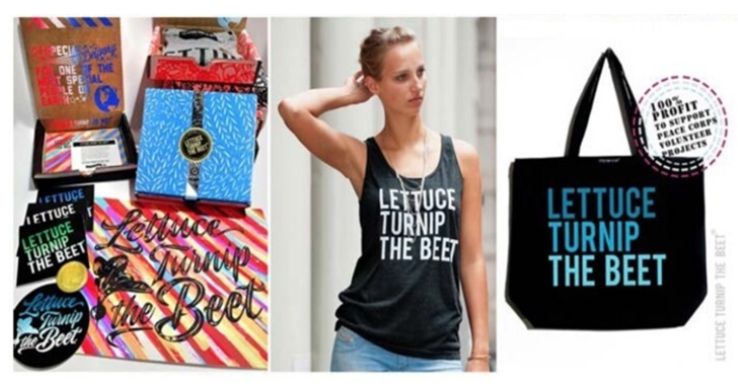

TTB, LLC is a small business that has seen success due to its vegetable-based pun LETTUCE TURNIP THE BEET.40 LTTB owns four trademark registrations for the pun for various apparel products, tote bags, and online retail store services, among other things.41 Many of LTTB's products are emblazoned with the phrase:

LTTB brought suit in the Northern District of California against Redbubble, Inc. in January 2018 for counterfeiting, trademark infringement, unfair competition, and false designation of origin.42 Redbubble is an online marketplace where independent artists can upload and sell their designs on everyday products such as apparel, tote bags, stickers, etc.43 Some of the designs available on Redbubble's website include LETTUCE TURNIP THE BEET:

In July 2019, the district court granted Redbubble's motion for summary judgment, finding that, under the doctrine of aesthetic functionality, LTTB could not prevent others from displaying the LETTUCE TURNIP THE BEET pun on products.44 LTTB "was not entitled to pre-empt use of the pun under the guise of trademark law."45 The district court, however, was careful to note that its ruling did not mean that LTTB has no viable trademark rights, just that LTTB cannot "preclude others from displaying the pun on products, absent a showing of source-confusion."46 The Ninth Circuit upheld the ruling, concluding that LTTB "failed to raise a triable issue that its marks serve the trademark function . . . ."47

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the district court's findings that the LETTUCE TURNIP THE BEET pun was aesthetically functional.48 First, it held that the district court did not erroneously rely on the test for aesthetic functionality articulated in Job's Daughters49 because the case remains good law and the result would be the same under the test as articulated in Au-Tomotive Gold, namely: (1) whether the alleged non-trademark function is essential to the use or purpose of the item or affects its cost or quality, and (2) whether protection of the feature would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage.50 It found that the t-shirts would still function as t-shirts without the marks, use of the marks did not alter the cost structure or add to the quality of the products, and exclusive use of the marks would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage.51 In short, LTTB presented no evidence that consumers buy its punny t-shirts because the t-shirts identify LTTB as the source, as opposed to because the consumers enjoy the aesthetic function of the pun.52

The Ninth Circuit also held that, given the district court's findings regarding functionality, the district court did not err in (1) failing to address uses of the marks on Redbubble's website and in online advertising and (2) the issue of likelihood of confusion.53 The Court also rejected LTTB's arguments that the district court improperly ignored LTTB's design marks and improperly relied on the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office's initial rejection of one of LTTB's trademark application as decorative or ornamental (the application was ultimately approved once LTTB submitted examples of the mark on product hang tags as opposed to on the front of its shirts).54

While infringement was not found in this case, it is clear from the district court's ruling that aesthetic functionality is not an impermeable shield. Placing a mark on a t-shirt, tote bag, or mug is not an automatic defense:

. . . [C]ompanies that have already established [a] famous mark

for selling a product—for instance, Coca-Cola, Volkswagen,

Audi, or Nike—may thereafter be able also to exploit consumer

interest in the mark by selling t-shirts or other products

emblazoned with such

marks, and preclude others from doing so

. . .

Redbubble instead appropriately frames the argument as precluding

LTTB from showing a likelihood of confusion as to source, where the

mere use of the pun on the face of various products cannot be

source-identifying.

. .

.

[N]othing in this ruling precludes LTTB from enforcing its rights

against a defendant who markets a products [sic] misleadingly

suggesting LTTB is the source.

LTTB, 385 F. Supp. 3d at 921-22.

In the end, the Ninth Circuit's decision has kept the doctrine of aesthetic functionality alive, while being careful to caution that source-identifying uses are not exempt.

Footnotes

1 Two Pesos, 505 U.S. at 765 n.1 (quoting John H. Harland Co. v. Clarke Checks, Inc., 711 F.2d 966, 980 (11th Cir. 1983)).

2 1 J. Thomas McCarthy, McCarthy on Trademarks and Unfair Competition § 7:63 (5th ed. 2021).

3 See TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 32 (2001) (citing Inwood Labs., 456 U.S. at 850 n.10).

4 1 McCarthy, supra note 3, § 7:63.

5 671 F.2d 1332 (C.C.P.A. 1982).

6 Id. at 1340-41.

7 Id.

8 TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 33-34.

9 Id.

10 Id.

11 Id.; see also Pub. L. No. 105-330, 112 Stat. 3064 (1998). See § 19:75 (ex parte bar to registration), § 20:21 (ground for opposition), § 20:56.50 (ground for cancellation), and § 7:84 (statutory defense to an incontestably registered mark).

12 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)(3).

13 See 15 U.S.C. § 1052(e)(5).

14 Ezaki Glico Kabushiki Kaisha v. Lotte Int'l Am. Corp., 977 F.3d 261, 264 (3d Cir. 2020).

15 Id.

16 Id. at 264-65.

17 Id. at 266.

18 Id.

19 Id.

20 Id. at 265-67.

21 Id. at 265-66.

22 Id. at 267-78.

23 Id. at 268.

24 Id.

25 Id. at 269.

26 Id.

27 Id.

28 Id. at 270.

29 Restatement (First) of Torts § 742 cmt. a (Am. L. Inst. 1938).

30 See Saint-Gobain Corp. v. 3M Co., 90 U.S.P.Q.2d, 2007 WL 2509515 at *31 (T.T.A.B. Aug. 31, 2007) (finding that the applicant had failed to demonstrate acquired distinctiveness and non-functionality of the color purple for sandpaper because a dark color, such as purple, was a natural by-product of the abrasive manufacturing process, often used in the coated abrasive industry to fill in uneven color patterns and for product coding, and thus constitutes a competitive need in the industry); compare L.D. Kichler Co. v. Davoil, Inc., 192 F.3d 1349, 52 U.S.P.Q.2d 1307 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (holding that the color compatibility of a brick finish on the plate of an interior lighting fixture with the color and decor of the furnishings does not alone make the design functional. "Mere taste or preference cannot render a color—unless it is 'the best or at least one, of a few superior designs'—de jure functional.").

31 1 McCarthy, supra note 3, § 7:82.

32 1 McCarthy, supra note 3, § 7:79.

33 See id.

34 See Vuitton Et Fils v. J. Young Enters., Inc., 644 F.2d 769, 774 (9th Cir. 1981) ("A trademark is always functional in the sense that it helps to sell goods by identifying their manufacturer.").

35 1 McCarthy, supra note 3, § 7:79.

36 Id. at 343.

37 Id.

38 Id.

39 Gucci Timepieces Am., Inc. v. Yidah Watch Co., 47 U.S.P.Q.2d 1938 (C.D. Cal. 1998).

40 LTTB LLC v. Redbubble Inc., 385 F. Supp. 3d 916, 917 (N.D. Cal. 2019).

41 Id.

42 LTTB LLC v. Redbubble, Inc., 840 F. App'x 148, 149 (9th Cir. 2021).

43 LTTB, 385 F. Supp. 3d at 917.

44 LTTB, 385 F. Supp. 3d at 920–22.

45 Id. at 918.

46 Id. at 922.

47 LTTB, 840 F. App'x at 149.

48 Id. at 152.

49 In Job's Daughters, the defendant produced jewelry bearing the plaintiff's collective membership trademark for sale to the members of plaintiff's organization. Int'l Ord. of Job's Daughters v. Lindeburg and Co., 633 F.2d 912 (9th Cir. 1980). Noting that the plaintiff did not produce any evidence of actual confusion, the court held that the defendant's use did not infringe the plaintiff's mark, in part because the application of the mark to jewelry worn by members was "functional" in that it enabled the wearer to "express her allegiance to the organization." 633 F.2d at 918. Like Pagliero, the reasoning of Job's Daughters has been forcefully criticized by commentators and courts. 1 McCarthy, § 7:82; W.T. Rogers Co. v. Keene, 778 F.2d 334, 340 (7th Cir. 1985) (rejecting Job's Daughters "as have most other circuits"); Univ. of Georgia Athletic Ass'n v. Laite, 756 F.2d 1535, 1546 (11th Cir. 1985).

50 LTTB, 840 F. App'x at 150.

51 Id. at 150-51.

52 Id. at 151.

53 Id.

54 Id. at 151-52.

* Co-authored by Max Jarquin, who is a summer associate at Finnegan

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.