The state of biosimilars in the US has never been hotter; 2017 was the most active year to date for biosimilar drug manufacturers since the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act (BPCIA) was enacted by Congress. Recent decisions by the Supreme Court of the US and the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit have indelibly altered the landscape of biosimilar litigation. Now, biosimilar applicants can eliminate the nearly eight-month information exchange process and/or collapse the two litigation phases into one single action − effectively expediting the litigation and potentially accelerating market entry.

Rounds of Disclosure

Enacted in 2010, the BPCIA created an abbreviated approval pathway for biosimilars (1). The BPCIA facilitates litigation during the period preceding FDA approval of the biosimilar so that the parties may attempt to resolve their patent disputes prior to commercial marketing (2). However, several key differences exist. Besides the absence of an Orange Book for patents covering biological products, the most notable distinction between the BPCIA and Hatch-Waxman schemes is how patent litigation can impact the approval and launch of a follow-on biologic. As set forth in 42 USC § 262 (l), a 'patent dance' is contemplated, consisting of several 'rounds' of disclosure and information exchange.

The first round of this dance starts rapidly. Within 20 days of the FDA's acceptance of an Abbreviated Biologics License Application (aBLA), the BPCIA contemplates that a biosimilar applicant provides the reference product sponsor confidential access to its full aBLA application (2). Furthermore, the biosimilar applicant can provide the reference product sponsor detailed information concerning the biosimilar product's manufacturing process (2). Sixty days after this initial exchange, the reference product sponsor must provide the biosimilar applicant with a list of unexpired patents for which a claim of infringement could reasonably be made, as well as any licensing offers (2). The biosimilar applicant then has another 60 days to provide detailed invalidity, unenforceability, and/or noninfringement contentions for each of the asserted patents (2). What follows next is an additional series of responses, culminating over an eight-month period, with the innovator bringing suit in a US federal court. However, if the biosimilar applicant fails to engage in this disclosure process, the reference product sponsor may file an immediate declaratory judgment action on any of those unexpired patents that could be reasonably asserted.

The second phase of the dance begins with a second notification by the biosimilar applicant that it will launch its product within 180 days. Both parties can initiate new litigation after this 'notice of commercial marketing'; innovators can bring actions for injunctive relief based on non-asserted (but previously listed) patents, and applicants can bring declaratory judgment actions for invalidity, unenforceability, and/or noninfringement against any innovator patent not pursued during the first phase (2).

Guidance from the Judiciary

Despite the carefully curated language of the BPCIA, disputes arose around the mechanics of this so-called patent dance. These were highlighted in the context of Amgen's NEUPOGEN® product and Sandoz's corresponding aBLA − the first BPCIA litigation. After submitting its aBLA, Sandoz opted to neither disclose its biosimilar application nor its manufacturing and relayed to Amgen that Sandoz would launch its biosimilar product immediately upon FDA approval, thereby effectively providing its 180 day notice of intent to commercialise. Based on Sandoz's decision not to comply with the aBLA disclosure requirement, Sandoz took the position that Amgen was entitled to immediately file declaratory judgment actions under § 262 (l) (9) (C) for patent infringement (2). In response, Amgen filed suit against Sandoz, asserting both state and federal law claims based on alleged violations of the BPCIA. The questions left for the courts to decide centred around Sandoz's conduct. These included:

- Is a biosimilar applicant required to disclose its aBLA

- What, if any, federal or state remedies are available if the applicant fails to participate in the information exchange provision in the first litigation phase

- When, exactly, must the biosimilar applicant give the reference product sponsor its 180-day notice of commercial marketing to trigger the second phase of litigation

Seven years after the enactment of the BPCIA, the Supreme Court addressed these issues. On 12 June 2017, the US Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision siding with Sandoz (3). The Supreme Court ruled that a biosimilar applicant is not required to disclose its aBLA; the only appropriate federal remedy for an applicant's failure to exchange information is a declaratory judgment action filed by the sponsor, as prescribed by the statute, and the applicant may provide its commercial marketing notice either before or after receiving FDA approval (3-4). However, the Court declined to rule on what, if any, remedies are available under a state law claim for a biosimilar applicant's failure to engage in the information exchange under 42 USC § 262 (l) (2) (A) and remanded this issue to the Federal Circuit (6). To aid the Federal Circuit on remand, the Supreme Court stated that the panel was free to assume that a remedy under state law exists and may first decide whether the BPCIA pre-empts a state law claim (3,5).

The Federal Circuit, on remand, determined that the BPCIA pre-empts Amgen's state law claims. Assuming that a remedy existed under state law, the three-judge panel first determined that Sandoz did not waive its preemption argument, even though the issue of pre-emption had not been previously addressed (4). The Federal Circuit found that pre-emption in the context of the BPCIA was "especially compelling" with the "interest of substantial justice at stake" (4).

Turning towards the issue at hand, the panel held that both field and conflict pre-emption exist so as to bar any state law remedy (4). Regarding field pre-emption, the court noted that "biosimilar patent litigation is 'hardly a field which the States have traditionally occupied'" (4). The Federal Circuit likewise found that Amgen's state law claims clash with the BPCIA in such a way that those claims are pre-empted. In the court's opinion, allowing state law claims "could 'dramatically increase the burdens' on biosimilar applicants beyond those contemplated by Congress in enacting the BPCIA" (4).

Impact on the State of Biosimilars

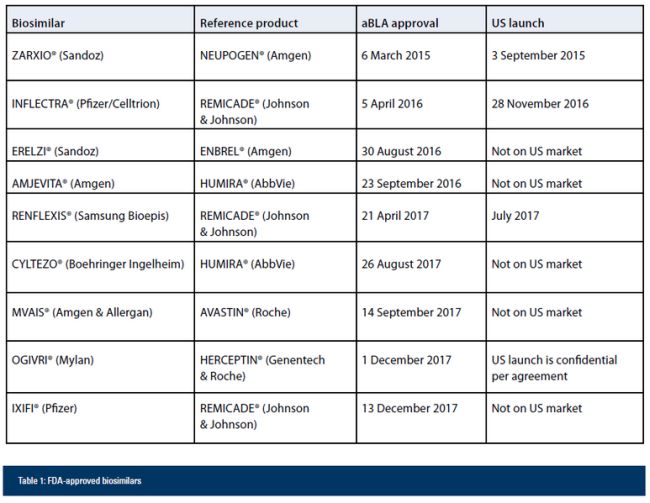

Biologics and biosimilars are a growing industry in the US and will continue to expand in the wake of these rulings. 2017 saw the approval of more than 20 aBLAs by the FDA, with three approved so far in 2018. Likewise, five new aBLAs were approved by the FDA in 2017 and 15 remain pending. Table 1 summarises the status pending and approved aBLAs. All but OGIVRI® and IXIFI® are the subject of pending litigation.

Unsurprisingly, the number of biosimilar suits filed in 2017 increased to 11, up from six in the previous year. This trend is expected to continue as the first quarter of 2018 saw five new cases filed at the district court level. The rise in biosimilar litigation may be in response to the most immediate impact of the Supreme Court's and Federal Circuit's decisions on the aBLA process − the opportunity for aBLA applicants to expedite the litigation process. As discussed earlier and confirmed by the two rulings, if a biosimilar applicant does not engage in the initial information exchange, the lone remedy is for the reference product sponsor to file a declaratory judgment suit. This declaratory judgment action has the potential to accelerate the first litigation phase by eliminating nearly eight months of negotiations between the two parties over which patents to litigate.

A second mechanism to shorten a suit under the BPCIA would be to collapse the two phases of litigation into a single action in a scenario where the biosimilar applicant provides its 180-day notice of commercial marketing contemporaneously with its notification to the reference product sponsor of its aBLA filing. This would collapse the 180-day waiting period prior to marketing into the corresponding litigation, such that they run concurrently. While this merger could allow the reference product sponsor to assert the entirety of its patent portfolio in one suit (without delay), it also allows an aBLA applicant to avoid waiting another 180 days before marketing its product once it receives FDA approval.

While biosimilar applicants do have these options to expedite proceedings, they do not always choose to do so. Some biosimilar applicants have decided to engage in the information exchange process, while others have declined. Interestingly, the decision to either forgo or comply with the disclosure requirement appears to centre on the particular biosimilar product at issue, rather than the biosimilar applicant itself. For instance, in the litigation surrounding ENBREL®, Sandoz − differing from its approach with NEUPOGEN − chose to provide Amgen with its aBLA and associated manufacturing information. Ultimately, an applicant can afford to be flexible in choosing a litigation strategy, but disclosure compliance appears to be tied to the specific product they seek to gain FDA approval and market.

The Future of Biosimilars

With 20 BLAs filed in 2017, three biosimilar products already on the US market, six aBLAs approved and awaiting launch, and 15 more aBLA applications before the FDA, the future of biosimilars and biologics is bright. However, interpretation of the BPCIA is still ongoing. What the recent decisions in the Sandoz versus Amgen line of cases have clarified is that biosimilar applicants have a range of options to dictate the pace of litigation prescribed under the BPCIA. How biosimilar applicants utilise these options, though, is product determinative and can vary even among the same applicants.

Footnotes

1 FDA, Title 12: Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009, §§ 7001-7003: 2010

2 US Code, Title 42: The Public Health and Welfare, § 262: 2010

3 Reuters T, Title 137: Sandoz Inc versus Amgen: 2017

4 Reuters T, Title 877: Amgen Inc versus Sandoz Inc: 2017

5 US Government Publishing Office, Article VI, The Constitution of the United States of America: 2017

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.