Introduction

We've all seen it. Patent attorneys love making up words. For example, instead of claiming a pipe, a hose, or a tube, we draft patent claims reciting "a fluid delivery system" or "a fluid conduit."

Why do we do it? Because it is our job to secure the broadest patent protection available for our clients. But these attempts at cleverness can backfire and result in uncertain claim scope at the time of enforcement because these made-up terms frequently open the door to arguments that means-plus-function claim interpretation under 35 U.S.C. §112(f) applies. If such arguments (typically raised by accused infringers during litigation) are successful, then your seemingly broad claims are limited to the example(s) described in the specification [and drawings] and "known equivalents."

The Statute

35 U.S.C. §112(f) is relatively unique in that it codifies a particular claim drafting tool/technique. At bottom, this statute is Congress' way of stating that you are allowed to claim something using only functional language, but if you do, be forewarned that the claim limitation will only cover the structure described in the patent specification and known equivalents:

(f) Element in Claim for a Combination.

An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.

35 U.S.C. §112(f)

Interestingly, we do not really see Congressional authorization of other claim drafting techniques elsewhere in the patent statute.

The most straightforward example of means-plus-function claiming follows the following format:

"means for [insert function, e.g., transporting water]"

It is important to note that in the above example, the claimed function of "transporting water" could be performed by something like a bucket in addition to a pipe, hose, tube, or other structure.

While this may seem relatively straightforward, what started out as a statutorily recognized claim drafting tool has become a trap for the unwary because patent practitioners can inadvertently trigger 35 U.S.C. §112(f) even though they had no intention of drafting a means-plus-function claim limitation.

How Did We Get Here? – the Williamson case

Ten years ago, there was less uncertainty regarding when to apply means-plus-function claim interpretation because a strong presumption existed that claims using the words "means for" or "step for" invoked 35 U.S.C. §112(f) (at that time pre-AIA 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶6) and that claims where those words were absent did not. See Greenberg v. Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., 91 F.3d 1580, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1996). That rule of law made a lot of sense given that Congress codified 35 U.S.C. §112(f) to give practitioners the option (i.e., the choice) to use or not use this claim drafting tool.

All that changed in 2015, when the Federal Circuit in Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339, 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2015) overturned the strong presumption that 35 U.S.C. §112(f) was invoked when the words "means for" "or step for" were used in a claim. A presumption still applies after Williamson, but it is no longer a strong presumption and the application of §112(f) now turns on the rather subjective determination of whether a claim uses a "nonce word" (i.e., a structureless generic term) in place of the word "means." The Williamson case itself gives examples, explaining that generic terms like "mechanism," "element," and "device" are nonce words that may trigger §112(f). Id. at 1350.

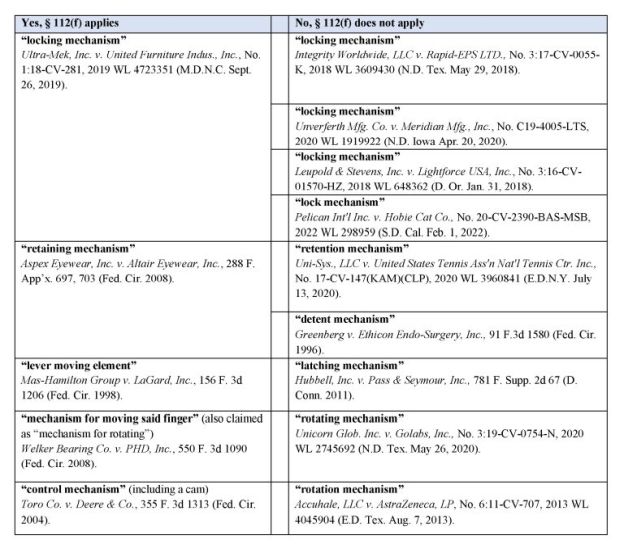

The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) gives further examples of non-structural generic placeholders that may invoke 35 U.S.C. 112(f): "mechanism for," "module for," "device for," "unit for," "component for," "element for," "member for," "apparatus for," "machine for," or "system for." MPEP 2181; citing Welker Bearing Co., v. PHD, Inc., 550 F.3d 1090, 1096, 89 USPQ2d 1289, 1293-94 (Fed. Cir. 2008); Mass. Inst. of Tech. v. Abacus Software, 462 F.3d 1344, 1354, 80 USPQ2d 1225, 1228 (Fed. Cir. 2006); Personalized Media, 161 F.3d at 704, 48 USPQ2d at 1886–87; Mas-Hamilton Group v. LaGard, Inc., 156 F.3d 1206, 1214-1215, 48 USPQ2d 1010, 1017 (Fed. Cir. 1998). However, this list is not exhaustive and has proven to be inconsistently applied by courts in the U.S. For example, the table below shows how the same or similar claim terms have been treated differently by different courts from one case to the next:

Ultimately, the determination of whether a particular term invokes §112(f) comes down to "whether the words of the claim are understood by persons of ordinary skill in the art to have a sufficiently definite means as the name for structure." Williamson, 792 F.3d at 1348. So, in district court litigation, the declarations and/or testimony of expert witnesses can play a large role in this determination.

At the other end of this spectrum are terms that connote structure and clearly do not trigger §112(f). Examples include "clamp," "container," and "lock." See Greenberg v. Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc., 91 F.3d 1580, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1996). From a practical standpoint, what is striking here is that the terms where §112(f) was found to apply usually sound like terms a patent attorney made up when drafting the application, whereas you can imagine the structural examples listed in Greenberg being used in common parlance or by engineers. So, a key take away for patent practitioners is that many §112(f) issues can be avoided if the terminology used in a patent application is consistent with what the inventor/industry calls certain components rather than names coined by the patent practitioner.

Dos And Don'ts – A Practical Example

Going back to the example provided in the introduction, imagine your client is a fire truck manufacturer and was the first to mount a water cannon on the end of the truck's extendable ladder. On your client's fire truck, water is supplied to the water cannon through a corrugated hose, which is what you describe in the specification. When you draft the claims, you don't want to limit the invention to the corrugated hose, so you come up with the term "fluid delivery system" and write the following claim:

- A fire truck, comprising:

a vehicle body;

a ladder that is pivotally connected to the vehicle body;

a water cannon mounted at a distal end of the ladder; and

a fluid delivery system for supplying water to the water cannon.

While this claim might appear acceptable to many, the last limitation exposes the claim to the risk of means-plus-function claim interpretation under 35 U.S.C. §112(f). Even though the claim shown above does not include the word "means," courts and the U.S. Patent Office have treated "system" as a nonce word and therefore equivalent to the word "means." See MPEP 2181; DYFAN, LLC v. Target Corp., 28 F. 4th 1360, 1370 (Fed. Cir. 2022). Moreover, the words before and after "system for" recite function rather than structure.

If §112(f) is found to apply, then your seemingly broad claim would be limited to covering embodiments where water is supplied to the water cannon through the corrugated hose described in the specification and equivalents thereof, which may or may not cover other options like telescoping pipe structures if they are not described in the specification.

If you chose to write the last limitation as "a fluid conduit for supplying water to the water cannon," you did better and there would be less risk that §112(f) applies. Notably, in TEK Global SRL v. Sealant Systems Int'l., 920 F. 3d 777, 787 (Fed. Cir. 2019), the Federal Circuit found that the word "conduit" recites sufficient structure to avoid means-plus-function claim interpretation under §112(f). But if you do not want to research the latest caselaw every time you coin a claim term, there is a better way:

Practice Tips For Avoiding Means-Plus-Function Claim Interpretation Under §112(f)

- Avoid the following nonce words: "mechanism for," "module for," "device for," "unit for," "component for," "element for," "member for," "apparatus for," "machine for," or "system for."

- Ask the inventor what they / the industry call certain components and use that terminology when naming claim elements

- Avoid using the word "for" as a transition word between the element name and functional language

- Avoid using purely functional language to describe a claim element (i.e., each paragraph of a claim should do more than simply describe what something does)

- Include structural language immediately after introducing a claim element (i.e., describe what the element looks like, what the element is connected to, what its components are, and/or where it is located).

- When in doubt, draft multiple independent claims that recite different variations of the limitation in question.

So putting this all together, a better way to draft the last limitation of the claim in our example would be to claim:

"a fluid conduit extending between an inlet end that is connected to a water source and an outlet end that is connected to the water cannon."

OR

"a pipe, hose, or tube connected to the water cannon to define a water supply passage."

OR

"wherein the water cannon has an inlet that is connected in fluid communication with a pipe, hose, or tube."

All of the above examples avoid means-plus-function claim interpretation under §112(f), while still covering a broad range of structures including the corrugated hose and telescoping pipe structures in our example.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.