Background

On February 23, 2021, after nearly five years, the USPTO issued to Warner Brothers U.S. Patent No. 10,926,179, entitled "Nemesis Characters, Nemesis Forts, Social Vendettas and Followers in Computer Games" ("the Nemesis Patent"). This patent is linked to the Warner Brothers' Nemesis System, which made its first appearance in the 2014 Lord of the Rings video game Middle Earth: Shadow of Mordor.

The Nemesis System, as Warner Brothers explains, is an innovative system "through which every enemy encountered in [the game] is procedurally generated and unique to each player, from appearance, to personality type, to strengths and weaknesses," and "can evolve to become a personal archenemy through the course of the game."1

Most companies would consider obtaining a patent after lengthy prosecution a victory. Some consumers, however, have expressed concerns that the patent may stifle creativity, is not in the spirit of game development, and is too broad in scope.2

While Warner Brothers' intentions for this patent are unclear,

many in the industry have asked: are game mechanic patents valid

under Alice? This patent, its history, and any future

litigation involving it, may help define this murky area of patent

eligibility.

Prosecution History

Nemesis Prosecution History & Context of its Examination at the USPTOAlthough the Nemesis Patent is directed to a game mechanic implemented in software, the USPTO did not challenge its eligibility under 35 U.S.C.A. § 101.

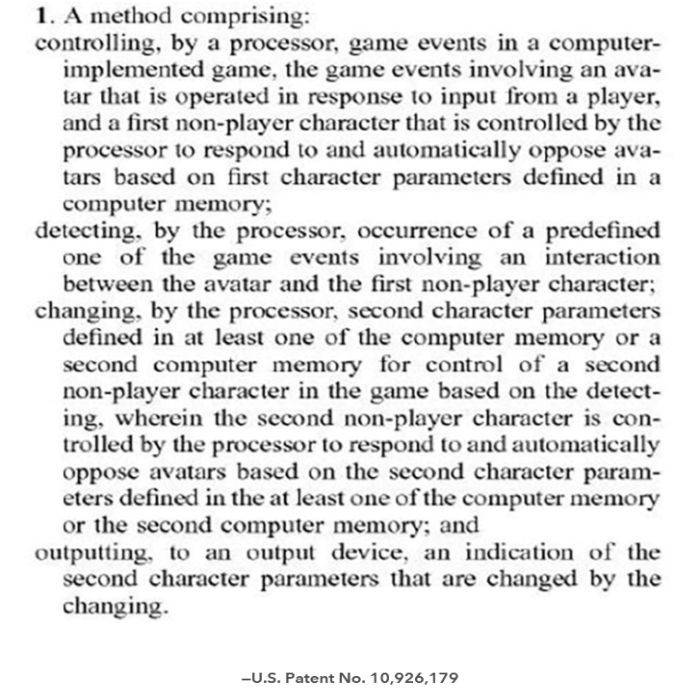

Claim 1 of the Nemesis Patent, for example, recites a method for controlling game events in a computer-implemented game, and includes a playeroperated avatar, a nonplayer character ("NPC") controlled based on character parameters, changing character parameters based on interactions between the avatar and the NPC, and outputting an indication of changed character parameters to an output device:

This claim recites no hardware other than generic computer components and appears to use these generic computer components for their ordinary uses. Nevertheless, the Nemesis Patent's claims never faced a 101 rejection. Instead, the Office's rejections focused primarily on prior art references under 35 U.S.C.A. §§ 102 and 103.

Since the filing of the Nemesis Patent, the rules surrounding how examiners consider 101 at the USPTO has evolved. When the Nemesis Patent's first Office Action was issued, the governing standard for analyzing claims under 101 was simply the twostep analysis under Alice/Mayo.

By the time the Nemesis Patent received its Notice of Allowance, the USPTO had issued its 2019 Revised Patent Subject Matter Eligibility Guidance.

The 2019 Guidance clarified for examiners how to apply 101. Under this Guidance, an examiner must determine if the claims fall within these groupings: mathematical concepts, certain methods of organizing human activity, or mental processes. If an examiner determines the claims fall into one of these groupings, then the examiner must determine if the abstract idea is integrated into a practical application.

Even though the Nemesis Patent was pending at the Office during the evolution of this guidance, the patent still issued without facing a 101 challenge.

An Alternative ExperienceWhile the Nemesis Patent did not face a 101 rejection, other gameplay mechanic related patents have. Analyzing a gameplay mechanic patent that overcame a 101 rejection can help one understand why the Nemesis Patent did not face this rejection during prosecution.

U.S. Pat. No. 10,471,357 entitled "Systems and Methods for Simulating a Particular User in an Interactive Computer System" faced three Office Actions rejecting the claims under 101. The '357 patent describes technology that allows a computer to simulate a user's style of game play.

The simulator includes a learning mode for monitoring a user's game play by detecting, recording and storing the user's response. In simulation mode, the simulator detects the occurrence of events, pulls from the stored data and outputs the user's simulated response to the event.

This simulation allows a user to experience what it is like to play against another user without requiring the other user's physical presence. Therefore, the '357 patent and the Nemesis Patent involve detecting the occurrence of events, generating a change to the game environment based on the occurrence and outputting the change to the game environment.

During prosecution, the '357 patent faced 101 rejections alleging the claims were directed to the abstract idea of data recognition and storage. The examiner further found the claimed invention did not include additional elements that amounted to significantly more than the judicial exception where the additional elements were recited at a high level of generality that performed the generic computer functions of receiving information and outputting a result.3

It would have not been surprising to see similar language in a rejection for the Nemesis Patent because both patents' claims include elements relating to data recognition and storage without significant additional elements (i.e., a processor and computer memory).

One counterargument may be that Claim 1 of the Nemesis Patent also recites language that ties data recognition and storage to the virtual video game environment such as "game events," "avatar[s]" and NPCs, and not just how a simulated user would play the game.

In support of a 101 rejection in the prosecution of the '357 patent, the examiner noted the claims were not patent eligible where conventional computer components were included to implement the abstract idea and the "necessary components required for a game service system [were] still absent from the claim language."4

In the response that resulted in withdrawal of the 101 rejection, the applicant amended the claims to add game service system language such as "a display for presenting a user interface ... the user interface being generated by said interactive computer program product."5

Conceivably, an examiner could find the Nemesis Patent's claims impose enough meaningful limits on the alleged abstract idea to avoid a challenge during prosecution, because the additional elements of game events, avatars and NPCs amount to significantly more than the judicial exception.

After the last Office Action was issued against the '357 patent, but before the applicant's amendments, the USPTO released the 2019 Guidance. The applicant successfully argued the patent did not fall into the groupings and, even if they did, the claims integrated the abstract idea into a practical application.

In particular, the applicant argued that even if the claims could be analogized to certain methods of organizing human activity, they recited more than receiving and/or transmitting data because they are directed to a computer system for associating data fields in a database that enables playing against a particular user's simulated playing patterns.

Regarding the practical application, the applicant argued the claims improved upon "conventional methods that do not consider the difference in skills, weaknesses, tendencies, strategies and behavior between a computer AI and a human opponent."6

In the '357 patent's Notice of Allowance, the examiner stated "[t]he claims are directed toward using categories to organize, store, and transmit information ... which have been identified by the courts as abstract ideas." However, the examiner found "the claimed gaming system, as amended, yields a specialized device distinguishable from a general purpose computer."7

Another possible reason that the Nemesis Patent did not encounter a 101 rejection under the 2019 Guidance could be because, like the '357 patent, the examiner found the claims do not fall into one of the groupings. For example, arguably the claims cannot be reduced to certain methods of organizing human activity because the claims focus on controlling and changing the activity of NPCs (rather than humans).

Alternatively, even if the Nemesis Patent did fall into one of the groupings, perhaps the claims could be found to integrate the abstract idea into the practical application of developing new methods and technologies for controlling NPCs to enhance enjoyment and appeal of the game.8

But like in the Nemesis System itself, avoiding one battle does not win the war. Although the examiner did not challenge the patent under 101, the true test likely still awaits — in the form of post-issuance challenges.

Post Issuance 101 Analysis - A Cautionary Tale

While the Nemesis Patent escaped 101 at the USPTO, that does not preempt an opponent from wielding 101 in litigation. The validity of issued patents can be and is often challenged when asserted in litigation.

If the validity of the Nemesis Patent were challenged under 101 during litigation, a court would evaluate the claims under the Alice/Mayo two-step test. Under Alice Step 1, a court would evaluate the claims to see if they are directed to patent-ineligible subject matter such as abstract ideas.

If a court finds the Nemesis Patent is directed to an abstract idea, the court would continue to Alice Step 2 to determine if the claims recite an inventive concept that transforms the claims into a patent-eligible application. The cases below may show a cautionary tale for the Nemesis Patent.

Under Alice Step 1, courts have found claims to be directed to abstract ideas where the claims focused on "'a method for delivering contextbased content' to a user" for a computing device9 (8,489,599 patent) and "increasing or decreasing the risktoreward ratio, or more broadly the difficulty, of a multiplayer game based upon previous aggregate results"10 (7,338,363 patent).

In reaching the conclusion that the '599 patent was directed to an abstract idea, the court found the claim language recited "receiving information, satisfying a condition, and presenting content to a user."11 The court that evaluated the '363 patent found the claims abstract because the patent taught "a game machine that updates the game conditions based on past results to keep the players engaged."12

The findings by the courts regarding the '599 and '363 patents show how a court may evaluate the Nemesis Patent under Alice Step 1. A court could find that changing gameplay based on past player actions reduces to the computer receiving information that satisfies a condition to which the computer then presents updated content to the player, similar to the '599 patent.

Or a court could find that changing gameplay based on past player actions reduces to a game machine that updates game conditions based on past results, like the '363 patent. Under these two interpretations, the Nemesis claims could be found abstract.

The courts evaluating the '599 and '363 patents also found those claims were abstract because they did not recite the technical means for achieving their functions, and were instead results-focused.13

It could potentially be argued that the Nemesis Patent is not results-focused because the claims recite changing gameplay in response to interactions between a player's avatar and NPCs and the changes are implemented by updating NPC parameters.

It is unclear whether this would make the solution technical. Ultimately, whether the claims and specification are detailed enough to show a technical (and not abstract) means of achieving its claimed result will be up to the courts.

Even if it is abstract, that does not mean the Nemesis Patent is doomed. Like the orcs of Shadow of Mordor, it could still survive, provided it claims something transformative under Step 2 of Alice. When analyzing the '363 patent under Alice Step 2, the court found the claims did not offer an inventive concept that would transform the abstract idea into a patent eligible application.14

The court noted the claim language included special names for each element, such as "transmitting device," and "gaming machine determining device." However, the court found the elements "remain[ed] generic computer parts invoked to effect the conventional computer task of gathering, manipulating, transmitting, and using data."15

Further, the court did not agree with the patent owner's argument that the claims provided an inventive concept of performing the abstract idea in an unconventional way in the gaming machine industry. The court stated that limiting the invention to the specific technological environment of gaming machines, without more, does not transform the claims into a patent eligible application of an abstract idea.

If the Nemesis Patent is found to be directed to an abstract idea, then the court would similarly evaluate if an inventive concept is present. It could be argued the Nemesis Patent does not possess an inventive concept because, similar to the '363 patent, the claims recite general computer components, such as a processor, computer memory and output device to achieve the abstract idea of updating a gaming environment based on past user actions.

Conversely, it could also be argued the Nemesis Patent claims possess an inventive concept. Unlike the claims in the '363 patent, the Nemesis Patent claims recite additional elements such as game events, avatars and NPCs.

The combination of these elements to change the gaming environment based on past interactions between the avatar and NPC by changing parameters of the NPC could be found to include an inventive concept to transform the abstract idea into a patent eligible application.

Conclusion

When it comes to video gaming patents, 101 is usually a significant challenge for patent-seekers. Overcoming a rejection under the ever-evolving 101 landscape during prosecution does not ensure a patent is immune to 101 challenges in later litigation. As such, companies interested in pursuing video game patents must be mindful of 101 law and how to leverage it when seeking and enforcing patents.

Footnotes

1 Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment Announces "Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor Game of the Year Edition," Warner Bros. (Apr. 29, 2015), https://bit.ly/3yoLGWg; Warner Bros. Interactive Entertainment Launches Video Game "Middle-earth: Shadow of Mordor," Warner Bros. (Sept. 30, 2014), https://bit.ly/2TAPd5o.

2 See e.g., Hayden Madsen, WB's Nemesis System Patent Will Only Make Video Games Worse, Screen Rant (Feb. 17, 2021), https://bit.ly/36gBKlJ; Rhys Wood, Warner Bros.′ Nemesis patent is terrible for the games industry - here's why, TechRadar (Feb. 13, 2021), https://bit.ly/2Ty8ww9.

3 Final Office Action dated May 5, 2017, p. 3–5.

4 Non-Final Office Action dated Sept. 26, 2018, p. 5–6.

5 Amendment and Response to Non-Final Office Action dated Feb. 26, 2019, p. 2.

6 Id. at p. 10.

7 Examiner's Reasons for Allowance dated June 4, 2019, p. 2.

8 See U.S. Patent No. 10,926,179 col. 2, l. 6–10.

9 Palo Alto Rsch. Ctr., Inc. v. Facebook, Inc., No. 2:20-CV-10753-AB-MRW, , at *1, *6–7 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 16, 2021) (denying Facebook's motion to dismiss the 8,489,599 patent under 101 where the court found the '599 patent is directed to an abstract idea but issues of fact exist under Alice Step 2).

10 Bot M8 LLC v. Sony Corp. of Am., 465 F. Supp. 3d 1013, 1020 (N.D. Cal. 2020) appeal docketed, Bot M8 LLC v. Sony Corp. of Am., 20-2218.

12 Bot M8, 465 F. Supp. 3d at 1021.

13 Palo Alto, , at *6–7; Bot M8, 465 F. Supp. 3d at 1023.

14 Bot M8, 465 F. Supp. 3d at 1024–27.

15 Id. at 1025.

Originally published by Westlaw Today

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.