Contents:

- Implementation and development of the intellectual property

- Legislation on the intellectual property – most important stages of development

- Form of protection

- Priorities of protection

- Rights acquired indirectly

- Preconditions of registration

- Specifics of the protection process of the intellectual property

- Specialized protection means in the civil procedure

-

- White areas" in the legislation on the intellectual property

- Application of legal norms on the intellectual property

- Concept of the intellectual property

- Piratism

- Summary

List of sources

The article deals with the main development stages of the intellectual property in Latvia. The practical implementation of the intellectual property started after regaining de facto independence of Latvia when, as per the decision of the respective government, preconditions were ensured to re-register those trademarks in the independent Latvia which were already registered in the territory of this state according to the USSR legislation. The Latvian legislation on the intellectual property, in turn, appeared only shortly after it. The main development stages are – adopting of the first laws in 1993; legislative amendments necessary to ensure Latvia's joining the World Trade Organization (in 1999) and the European Union (in 2004). Conceptual foundation in legislation has been little changed and they are: protection of intellectual property based on registration (registration system); registration is secured after the formal preconditions for registration are fulfilled. No requirement is set forth for the expertise of the intellectual property object in point of fact (patent novelty, confusing similarity between a trademark and a design with the competing objects). Several types of intellectual property are not either regulated (domain names, trade secrets, rights to an image) or else are regulated insufficiently (sui generis database rights).

The concept of intellectual property in the Latvian law science was analyzed considerably later – approximately 10 years after the legislation was enforced regulating individual types of intellectual property. A narrow understanding of the property still prevails in the law science and court practice. Intellectual property is regarded as an incomplete property object by many law experts. Many types of intellectual property, like domain names, are contested in the court not to be regarded as property objects. Such doctrine not only contradicts the already established court practice, e.g. the practice by the European Court of Human Rights, but is also putting obstacles to the practical development of the intellectual property.

1. Implementation and development of the intellectual property

The history for the development of the intellectual property is quite short after regaining Latvia's de facto independence. In the given case there is no reason to have a retrospective look at the period from 1918 – 1940 as the laws of that time were not restored. However the term of intellectual property per se had the key role in transforming the Latvian economy from a centralized state regulated economy to the market economy. Discussion about transformations in the property system started in the summer of 1989 in the Supreme Council of the Latvian SSR: There is necessity for different forms of property, of equal status, it is necessary to have equivalent exchange, free market of goods, services, intellect"1.

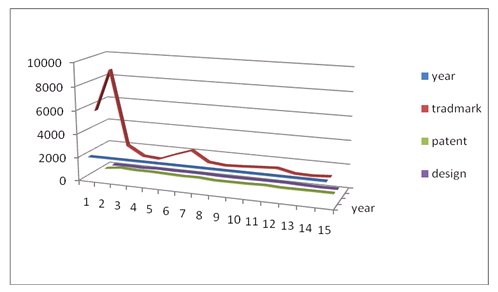

Historically the first source is – Decision adopted by the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Latvia On temporary procedure for protection of inventions, industrial designs and trade marks in the Republic of Latvia"2. This document may be regarded as a starting point for revival of intellectual property after Latvia regained its independence de facto. It is exactly this decision which established preconditions for intellectual property in Latvia and such property was created literally at this very moment as it was the precondition for the registration boom" of the intellectual property rights, like it is also reflected on the home page of the Patent Board of the Republic of Latvia demonstrating the dynamics of the patent and trademark registration with the sharp rise in 1992 (see Diagram no 1).

Diagram no 1

This diagram is an example of the strength and weakness of the intellectual property in the Republic of Latvia. First, the diagram demonstrates an uneven rise when the number of registered objects reached several thousands within a short period, afterwards in the successive years it became stable with a considerably smaller amount. Second, the diagram shows the asymmetric character of the intellectual property protection. Only one segment of the intellectual property – trade marks – experienced sharp rise with the rest remaining low. It is significant that the preconditions for re-registration" were created even before the preconditions for registration" were worked out as the respective laws on registration of trademarks and patents were only in the draft stage. A fair question arises – how was it possible to re-register the already existing old" trademarks if there were no preconditions for such registration procedure. The only explanation is that already from the very beginning the expertise of the intellectual property to be registered was not required as a precondition. Respectively, the re-registration of the old" trademark took place without considering a possibility that the mark might be confusingly similar to some local mark and could be contested before the local court since neither the objection preconditions nor the procedure existed altogether.

This tendency reflects the extravert" nature of the Latvian intellectual property which is more expressed as a reaction towards the processes elsewhere, outside Latvia than legal consolidation of the innovations developed in the state – the trademarks developed abroad are re-registered in Latvia mainly in a way of the imported goods and marketing instruments. While the rest of the intellectual property objects actually languishes, including one of the main indicators of the local scientific creation products – patents.

It is not possible to schematically reflect protection of all intellectual property objects as some of the intellectual property objects, e.g. copyrights, database rights (to a certain extent also designs as from 2004) are in force" and thus protected without registration. However, also to these development spheres of intellectual property one may attribute an assumption that at least within the early stage of the intellectual property development, Latvia has been a passive absorbent of intellectual property objects.

Out of all intellectual property spheres, the copyright sphere (computer programs) could be the most perspective for Latvia as a potential exporter of innovation products, i.e. with respect to the intellectual property objects protected irrespective of their registration. Yet in this sphere the potential obstacle is the excessive accent on the author's rights (in disadvantage of the rights of the consumer and the indirect acquirer of the work, see Chapter 2).

In comparison with the earlier period with the legislation recognizing the rights to a private patent only within a restricted form (with extensive rights by the state to exercise a forced license), mostly for the foreign subjects3, to a restricted range of objects, without admitting the patent capacity4 for substances, including medicine, and within a limited number (within 10 years i.e. from 1942 -1952 only 385 patents were submitted in the entire Soviet Union5) , possibly there might be established a regress instead of a progress i.e. the number of the protected patent-capable innovations in Latvia under the USSR could have been considerably higher, yet bearing in mind that they were not owned by separate individuals, protected by patents.

In this way one can get an impression that the factual development of the intellectual property was import-oriented from the very beginning. The true reasons for such tendency might be also other, e.g. the small number of patents is also explained by the collapse of industry, poor science financing etc. Still this tendency is programmed in the very patenting system which is oriented to the issue of weak patents (see Subchapter d) under Chapter 2).

2. Legislation on intellectual property – most important stages of development

Laws on individual types of intellectual property were adopted in 1993. The next development stage is related to Latvia's joining the World Trade Organization (1999) and the European Union (2004).

The Latvian law of 15.05.1993 On copyrights and neighbouring rights" shows eclectic approach to the conceptual matters. E.g. according to Article 11 of this law "producers shall be recognized as the authors of audio-visual works", besides, the latter is defined as a persona who has undertaken obligation to create such (i.e. audiovisual – J.R.) work". The producer as an author is a legal construction unfamiliar to the law system of the Continental Europe, while the definition given in the mentioned law is simply a defect.

Whereas the initial wording of the Patent law dated 31.03.1993 already contained all the preconditions for the issue of a weak patent which was also characteristic for the wordings of the laws dated 1995 and 2007 (see subchapter d) of this chapter). Approximately at the same time the laws on Protection of designs (10.06.1993), on Protection of plant varieties (03.06.1993) and on Protection of topographies of semiconductor products (12.03.1998) were adopted. On 07.09.1993 Latvia reviewed its membership in the Paris Convention on protection of industrial property (Paris convention).

By the Cabinet Regulation no 197 dated 18.04.1995. On renewal of presence of the Republic of Latvia in the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works" occurred several, poorly researched problems in the law science. First, it is a matter of a constitutional nature related the peculiar form – renewal of presence" based on the Cabinet regulation instead of the law. According to Article 68 of the Latvian Constitution all international agreements, which settle matters that may be decided by the legislative process, shall require ratification by the Parliament. Also the law on the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works adopted on 26.06.1936 was not renewed, but adopted at the time when the Constitution was suspended. It turns out that the legally deformed joining to this convention which could be somehow understood within the authoritarian spirit of the 30ties of the previous century has to a certain way ensured its continuity" by the mentioned Cabinet regulation. Second, it is essential to establish to what extent the principles and legal norms of this convention are applicable in the time period before renewal of presence", especially bearing in mind the context of the copyright law of that time which cannot be always harmonized with the principles and legal norms under the Berne convention.

Both these issues are interrelated. With the lack of more profound researches in the constitutional and international law, it is impossible to draw any convincing conclusions with regard to the private law consequences from this situation. However, making use of the peculiar vacuum of theories, it may be presumed that for the sake of ensuring the interests of the intellectual property institute, it would be better to give a confirming answer to the both questions arising from the given situation – respectively – whether the Latvia's participation in the Berne convention should be regarded as sufficient despite the mentioned defects to allocate precedence to the convention norms over the national ones that contradict these norms and – whether such principle should be also attributed to those norms of law which were in force before Latvia's renewal of presence". Besides, this principle would be attributable both to the norms that were adopted after Latvia regained its de facto independence and to the legislation of the earlier period. Such assumption could be grounded on the idea about the continuity of the legal regime in the pre-war Latvia. It is self evident that the given conclusion needs more profound substantiation exceeding the scope of this article.

By evaluation of the impact of the bilateral international agreements on the intellectual property rights, an important role was played by the fact that Agreement on trade relationships and protection of intellectual property rights between the Republic of Latvia and the United States of America was concluded (in force since 20.01.1995). Although this agreement provides bilateral obligations, in practice due to understandable reasons it has caused considerably broader obligations for Latvia in relation to protection of the USA patents in Latvia assigning at least 20 years from the date of filing of the patent application or 17 years from the date of grant of the patent" (Article 6, Para 4) as well as a Party shall provide transitional protection for products embodying subject matter for which product patents were not available prior to February 28, 1992" (Article 6, Para 5). Such obligation shall be satisfied if a patent has been issued for the product by the other Party based upon an application filed twelve months or more before the date on which product patent protection became available for that subject matter, but not before February 28, 1984". In this way the agreement ensures a retroactive attribution of Latvian patent rights to the USA patents.

The next stage in the development of legislation is related to the year 1999 when Latvia became a member of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and afterwards – joined the European Union in 2004. The membership in the WTO caused necessity to ensure protection of geographical indications. It is however true that the duty to ensure protection of geographical indications is set forth also by Section 2 of Article 1 of the Paris convention where among protection of other intellectual property objects also "indications of source or appellations of origin" are mentioned. The Paris convention also refers to differences between trademarks and geographical indications stating that trademarks, which consist exclusively of signs or indications to designate place of origin of the goods, can't be registered as trademarks" (6. quinquies Article B, 2 subparagraph). The Paris convention also ensures protection mechanism, namely, seizure of goods bearing false indications as to their source or the identity of the producer (Article 10). Confusing indications about origin of the goods refer exactly to the protection of geographical indications. According to Article 19 of the Paris convention the countries of the Union reserve the right to make separately between themselves special agreements for the protection of industrial property, in so far as these agreements do not contravene the provisions of this Convention.

In the Latvian legislation protection of geographical indications was provided for the first time by the law On trademarks and geographical indications" (in force since 15.07.1999). When Latvia joined the EU it was bound by Regulations on protection of geographical indications. Protection of geographical indications within the EU has a wider context. The Madrid Agreement for the Repression of False or Deceptive Indications of Source on Goods was signed in 1891 simultaneously with the well known Madrid Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Marks supplemented by the Madrid Protocol of June 27, 1989 to which also Latvia joined by the law of 1999 (in force since 17.09.1999, published: Latvijas Vçstnesis - 1999. - 17. sept. - Nr. 305/307). Section 1 of Article 1 of the Madrid Agreement on geographical indications provides all goods bearing a false or deceptive indication by which one of the countries to which this Agreement applies, or a place situated therein, is directly or indirectly indicated as being the country or place of origin shall be seized on importation into any of the said countries.

The International Convention on the Use of Appellations of Origin and Denominations of Cheeses (known as Stresa Convention) was signed in 1951. This convention however has only a historical meaning as its content was incorporated in the EC Regulations in the course of time which successively replaced one another, also the currently effective Regulation no 510/2006 dated March 20, 2006 on the protection of geographical indications and designations of origin for agricultural products and foodstuffs. 6

Lisbon agreement on Appellations of Origin was signed in 1958. In this document appellations of origin are defined as the geographical name of a country, region or locality which serves to designate a product originating therein, the quality and characteristics of which are due exclusively or essentially to the geographical environment, including natural and human factors. In difference from the Stresa Convention whose provisions have become the inner regulations of the EU, the range of members of the Lisbon agreement is quite multiform. The first countries who ratified the Lisbon agreement were Cuba, Haiti, France, Israel, Mexico and Portugal. Lisbon convention provided the international registration mechanism for appellations of origin. Based on it, 844 appellations of origin were registered out of which 774 are still valid.7

The European Union has a similar system for protection of geographical indications providing a general regulation for agricultural and food products, except the strong alcoholic beverages and wines by ensuring strengthened protection for alcoholic beverages. With respect to agricultural and food products the European Council Regulation 510/2006 dated March 20, 2006 is in force at the moment, while with regard to the strong alcoholic beverages – the European Council Regulation no1576/89, with respect to wines – the European Council Regulation no 1493/1999. A detailed analysis of the content of the two latter regulations is given in the publication by V. Mantrovs.8 The supplemented and renewed regulation of 2006 about agricultural and food products is published in the official journal of the European Union (OJL 93/12 31.3.2006.). Regulation no 1576/89 contains Appendix II where also the geographical indications applied by Latvia are included: Rîgas Melnais Balzams, LB Vodka, LB Degvîns, Rîgas Degvîns, Allaþu Íimelis and Latvijas Dzidrais.

Agreement "On Accession to the European Union" (Accession treaty) signed on April 16, 2003 with the total amount of 5800 pages, provides the technical adjustments of the EU secondary laws (decisions, directives, regulations) in one of the four appendices referring to all candidate states necessary to ensure application of these legal acts after the new candidate states accede the EU. This appendix sets forth technical adjustments in legal acts regulating free movement of goods, persons and services; rights to establishment, competition policy; agricultural, fishery, transport policy, tax policy, statistic, social policy and employment, energy. This appendix also ensures specific provisions with regard to trademark rights, geographical indications, designs, plant varieties and patents9.

The first literature on intellectual property appeared in Latvia considerably later. Due to this reason no theoretical preconditions were available for the law drafting, only very general ideas that such legislation should be drafted. Likewise there were no landmarks to decide important conceptual issues. In any drafting of the intellectual property legislation it is essential to decide:

- on protection forms (registration or usage system);

- on protection priorities (subject or user priority);

- on indirect acquirers of works (works for hire);

- registration preconditions.

a) Form of protection

With regard to the first question, the answer came out per se. Without special theoretical discussions the registration system was adopted regarding industrial property objects – trademarks, patents, designs, plant varieties – but with respect to copyrights, also as self evident, the Berne convention principle was incorporated that in order to establish copyrights, no formalities are needed. Possibly it has nothing to do with the fact that the Latvian law system falls within the range of Roman-German law. Rather the decisive meaning was to the fact that the major part of the working group drafting the first legislative proposals became the patent attorneys, but the minor part – the responsible employees of the newly established Patent board. Thanks to this fact the registration procedure of intellectual property was implemented in time and following the above shown diagram, went on successfully. It is another point whether the registered rights were more or less valuable (see subchapter c)).

b) Priorities of protection

The question of protection priorities was much more complicated. In case of intellectual property there is contradiction between the intellectual property subjects (owners) and users. The absolute monopoly of the intellectual property rights is in conflicts with the public interests to use the product of creation. Usually this conflict is solved by the help of the so called forced license10.

Even terminology is different in this sphere. Supporters of the authors' ownership rights refer to these restrictions as exceptions". While the supporters of the users refer to the users' rights" or even to the public rights".11 The issue about the users' rights is closely related to the amount of exercise of the author's moral rights. Express restriction of the user's tendency goes hand in hand with the author's absolute rights to act with the product of his creation. The most expressive way of the moral rights may be found in copyright conception recognizing the author's rights to withdraw the work.

The right to withdraw the work is the right to request that the use of the work is suspended. In literature the right to withdraw the work is defined as absolute, respectively, "the author's wish to exercise it is binding both to the persons who are engaged in contractual relations with the author (e.g. a publisher) and to the rest of the persons. The right to withdraw a work provides the author with a lawful chance to unilaterally withdraw from the obligations under the contracts".12 This right that is recognized by the Continental Europe law systems, but unfamiliar to the Anglo-American law, has very different scope in different countries exactly for the reason that the nature of this right is absolute. However, at the same time it is in an incompatible contradiction with the concept of the intellectual property per se as this right is inherent to personal or moral rights category which, due to their inalienable nature, cannot be included in the intellectual property concept. In opposition to several other personal rights, e.g. the right to the word, immunity of the work etc., the right to withdraw the work has not even been expressly referred to among the rights pertaining to the author in the Berne convention. Indirectly the right to withdraw the work may be derived from the other author's moral rights, e.g. the right to decide the legal fate of the work. Due to its absolute nature, the right to withdraw the work may come into conflict with the agreements signed by the author about the usage of the work. Although within such circumstances the rights inherent to the user are protected by the right to claim compensation of damage incurred in the result of such withdrawal, in practice such rights may turn out to be incommensurable since the author as a physical person may be short of resources to compensate the damage incurred due to withdrawal of the work. Because of it, the right to withdraw the work is usually restricted by law, e.g. its usage is not possible with respect to several specific types of work like computer programs, collective work being conglomerate of several authors, e.g. films, broadcasts etc.

The right to withdraw the work normally cannot be exercised for just any reason, e.g. the German legislation provides that withdrawal of the work may take place only if the author cannot accept the content of the work any longer, it does not comply with his personal views or principles. Italian laws, in turn, provide that withdrawal of the work may take place due to "serious moral reasons". The same refers to France.13 Legislation may set forth restrictions to withdraw specific types of work stating that this right does not imply, let's say, films (Germany), computer programs (Russian Federation) or that such withdrawal with regard to the computer programs is only valid when specifically agreed upon (France).

As per the laws of England, the right to request that the name of the author is shown on every copy, is not attributed to the computer programs.14 In circumstances when such restrictions for the exercise of the author's immaterial rights are not defined, one can come across a fully autocratic exercise of such right in disadvantage of the user. Consequently, the balance between the author's and user's rights has essential meaning.

Latvia expressly stands out among other countries by the fact that none of the above restrictions can be found in our legislation. This situation often turns the users into hostages by the impulsive actions of an individual author. In the end, however, the authors themselves are the sufferers. With the chance to choose between the Latvian and any foreign author, the latter will have advantageous position on the market considering the fact that the rights of these authors to unmotivated withdrawal of the work will be reasonably restricted in the interests of the users and will better ensure a guaranteed and unrestricted use of the work. Besides, the paradox here is that exactly due to its inalienable nature, the right to withdraw the work by lowering competitiveness of the Latvian author, e.g. on the market of computer programs, is something which cannot be restricted by the author per se since any respective agreement will be regarded as invalid before the court.

Certainly when the intellectual property legislation was drafted, especially within the dominating "laissez-faire" atmosphere or total economic and legal liberalism, the preference was instinctively given to the author's absolute, unrestricted rights conception where reasonable restrictions in the public interests had minor role. For example, neither in the first (1993) nor in the second (1999) copyright law we find restrictions to the right to withdraw a work either with regard to computer programs or collective works in general, or databases especially. Likewise there are no restrictions to the author's right to be indicated as an author. With a consequent application of these rights, any computer program should be then full of different surnames of authors all over. We are saved from such situation only because similarly to numerous other cases, there is a difference between the theoretical prescriptions and their practical application. Partially it is also explained by the fact that authors are not fully aware of the unrestricted manipulation potential incorporated in the legislation about specific objects of law, like computer programs and databases. The specific Latvian situation can pay back" exactly onto the authors. Purchase of the works by foreign authors carried out through different agencies is viewed as a purchase of any goods where the right to withdraw the work is not considered altogether15.

It should be noticed that such system may turn out useless when a contract is signed about the usage of a work whose first edition was experienced in Latvia. Although in the Latvian legal literature the transfer of a work is described as cession, still as it should be kept in mind that a contract is signed about the use of the work whose first publication was in Latvia, the quoted author states that everything that is discussed further on only refers to material law"16. If so, there is also no grounds to define the transfer of such material" rights as cession since a deed may be revoked while the right per se – is inseparably related to the assignor, thus – cannot be ceded within the meaning of the Civil Law of Latvia (Article 1799).

c) Rights acquired indirectly

Considering that only a physical person is capable of carrying out intellectual creation, legal persons cannot acquire intellectual property rights based on the authorship. The only exception refers to sui generis rights of a database creator. While the question in what way and whether in general a legal person acquires intellectual property rights, is one of the central ones in the intellectual property theory.

Initially we do not find a consequent position in the legislation in the matter about the intellectual property rights of legal persons and the grounds for their occurrence.

Due to the reasons described in the previous sub-chapter, any deed by which the copyrights are transferred to another person (rights acquired indirectly), acquires the nature of unconditionally revocable transaction. A similar situation is with respect to the rights acquired based on the employment agreement. In all cases, with the only exception of the computer programs created by an employed person (according with the law of 1999, but not with the law of 1993) there is presumption that in case of doubt these rights are maintained by the author instead of the employer.

d) Preconditions of registration

Also with respect to the preconditions for acquisition of rights through registration, the law initially provided almost unrestricted liberalism. The most expressive sample of such kind of liberalism is abandonment of the patent, trademark, design expertise in the essence. The proposal by the working group – not to carry out the patent expertise in relation to compliance of the patent application with the technical level (by alleging with the lack of resources) – was implemented into the Patent law of 1993 and also maintained in the Patent law of 1995 and 2007. This proposal had far reaching consequences.

First, it is registration of weak patents. It was obvious from the very beginning that by such reviewing of patent applications weak patents will be registered that are easy to be contested by reference to the previous technical level. It is practically impossible to protect a patent against the rights of the earlier registered patents if existence of such rights has not been even checked when the patent is registered. In this way the patent was not regarded as an object of ownership rights to be really protected. Only those patents were valuable that were registered abroad and thus undergone the priority test and maintained their value also after their attribution to Latvia.

Second, it was the state's release" from the duty to ensure preconditions for the patent expertise. Considering the fact that the necessity to compare the patent application with the existing technical level has fallen off and consequently also the necessity to accumulate data about the existing technical level, i.e. the action by which usually the patent registration expenses are substantiated (the state duty), the only justification to collect such expenses is contribution to the budget. In the result the Patent board, since its very foundation, was perceived as a dairy cow" whose main, if not the only function, is to ensure contributions in the budget and – as one of the inevitable by-products – lack of any justifying grounds for additional financing in future. In the result the Patent board of the Republic of Latvia, as to the number of employees, may only be compared with the patent institution in Iceland and is considerably smaller than in the rest of the Baltic States. It is self evident that this situation did not enhance the total dynamics of the budget filling since with the lack of respective incentives the number of the registered patents has remained unchanged in the course of time.

Third, such attitude stimulated additional brain drain factor which is not found in other post-communist countries – the outflow of innovations abroad even though the brain" i.e. the inventor, stays in Latvia. The low number of the registered patents has several explanations – decline in industry, poor science support etc. Researches have not been carried out about the impact of every individual factor. Still it is clear that a patent registered in Latvia has incomparably weaker chances to be protected against any claim based on the objections of the earlier registered patent and may serve as a reason for the patent inventors to register their patents in any country where the patent capacity is checked through expertise which is not so in Latvia. Therefore it is not surprising that Latvia lags behind also in the sphere of innovations. According to the research done by the World Economic forum on the global competitiveness, Latvia takes the 36th place as per this indicator being behind for 11 positions from Estonia and for 4 positions – from Lithuania.17

Fourth, with the lack of the patent expertise foundation, Latvia has very weak chances to successfully defend itself from the patents that are registered in other countries and attributed to Latvia, even if as per the technical level here in Latvia, it would not be recognized as a new one and thus would be contested. Frequently, such patent could even turn out to be the result of the research carried out in Latvia that has emigrated", e.g. in the 90ties together with some researcher and now has returned in a form of a patent registered abroad and attributed to Latvia to stand across the road of the co-authors of this research in Latvia or else – if the product invented on the basis of such research is exported – to block the import of this product to which it is attributed to. Normally in such situation the patent would be contested based on the fact that it does not exceed the previous technical level, to be more particular – is the result of the research carried out in Latvia. However, with the lack of any qualitative research that would normally be ensured by the expertise of the patent institution, initiation of such process, besides – in the jurisdiction of another country, would mean a blind drive nowhere by putting under risk not only the resources of the patent contester, but also the chance that in case the proceedings are lost, the court expenses may be collected by the owner of the contested patent. It should be noted that the latter would not undertake the similar risk because the Latvian procedural legislation which allows compensation of the court expenses only within the amount set forth by the Ministry of Justice, turns such collection into useless instrument, although otherwise the chances to dispute the patent are good. This defect that was initially worked into the legislation gets more and more difficult to be overcome – the wider the bad news" about the patent weakness spreads, the lower is the motivation to cure" this cause, and simultaneously – the willingness to register new patents, i.e. Ostwald's (the only winner of the Noble prize who has worked in the territory of Latvia) ripening process which by reference from the nature processes to the society development tendencies is if you wish, the process in the result of which the rich become richer, but the poor – poorer".18

e) Specifics of the protection process of the intellectual property

Requirement for the special court

In many countries the intellectual property disputes are reviewed by special courts, or if within the general courts – by the judges having respective training. Usually it means that that such person, alongside with the legal education and experience, has also acquired respective technical education. Specialization idea has also been reflected in the Latvian legislation in 1993 when the first laws on the intellectual property were drafted and adopted. In most cases these laws envisaged that the disputes arising from the industrial property rights were admissible to the Riga Regional court as the court of the first instance. Such admissibility was also defined in the later laws, e.g. in the law On trademarks and geographical indications, in the Patent law, in the law On designs. In the result this court gathered the greatest experience in reviewing industrial property disputes. Also, a restricted number of judges engaged in this dispute resolution who in addition to the general qualification, participated in sessions and conferences related to the protection of intellectual property rights in the court. Besides, their experience was contributed by the frequent reviewing of disputes related to the intellectual property. However, this principle is not attributed to all objects of the intellectual property. Special admissibility is not provided by the law On protection of plant varieties, the Copyright law. Considering that special regulatory acts have not been adopted with regard to several intellectual property types, e.g. domain names, there is no special admissibility provided.

Besides, there were also other factors. First, not all intellectual property cases inevitably were reviewed before the Riga Regional court as the court of the first instance. Disputes arising from copyrights and other disputes whose special admissibility was not expressly provided in the respective laws, e.g. disputes related to domain names, were reviewed by district or city court as the courts of the first instance according to the general admissibility provisions, i.e. following the defendant's place of residence or location. The court of appeal in these cases was the Riga Regional court which, as described above, was indicated as the court of the first instance for the most intellectual property cases.

Since frequently the intellectual property disputes are raised by filing application in the Competition council, but its rulings, in turn, are appealed in the district court, the hierarchy of the court system was different also in these cases. Since February 1, 2004 due to establishment of the administrative court system and with enforcement of the Administrative procedure law, this system was substantially revised once again and the Latvian court system moved away from the original specialization idea in the intellectual property disputes even more. Due to implementation of the administrative procedure, a sharp line was drawn in the intellectual property protection between the administrative procedure and the action procedure. Considering the specifics of the intellectual property protection, namely – that in great number of cases the precondition for the intellectual property protection is registration of the respective rights in the Patent board or other institutions, all disputes of the interested persons related to the registration procedure shall be appealed in the Administrative district court as from February 1, 2004. Under the appeal procedure they are reviewed by the Administrative regional court, but under the cassation procedure – by the Senate for the Department of the Administrative cases.

Taking into account that the earlier system of proceedings is maintained with regard to the action procedure, there is a chance that one and the same matter, like the patent novelty, indistinctiveness, confusing similarity between trademarks, invalidity etc. are reviewed in both types of proceedings. For example, a complaint may be filed in the Administrative district court about the ruling adopted by the Appeal council of the Patent board, however, the interested person has also rights to raise in parallel an action, let's say about cancellation of the registered mark which then should be reviewed in the Riga Regional court as the court of the first instance. Theoretically there is not even excluded a chance that in two different court systems the interested person gets totally opposite results, e.g. the Administrative court sustains the ruling adopted by the Appeal council of the Patent board, while the general court system with the Riga Regional court as the court of the first instance draws totally opposite conclusions, besides both judgments will have equal force. No such cases have been encountered by now and it is hard to believe that there actually will be, however all in all such diversification of the dispute resolution does not contribute to the specialization idea of the courts. It also contradicts the idea incorporated under the European legal norms about necessity to ensure operation of the specialized court in the intellectual property sphere.

Certainly, the court specialization degree is not the only criterion. It is also important how promptly the court reviews cases of the respective category. The number of the appealed cases is also an important criterion. The Latvian court system is not popular with efficiency. In difference from the United Kingdom, Germany and some more where the number of the appealed cases is less than a half (it is explained by the effective work of the courts of the first instance and the adequate evaluation of the case which is not presenting arguments and motivation for the partiers to spend on the expensive appeal procedure knowing that the result would be the same), the number of the appealed cases in Latvia is relatively very high.

It would only be logical following the above mentioned requirement if exactly the Riga Regional court were announced as the specialized court in Latvia. Such announcement was made on November 24, 2005. In Latvia the Riga Regional court was defined as the court of the first instance for the Community Design court to review design disputes, while the Civil Case panel of the Supreme Court was defined as the court of the second instance. Unfortunately, the idea of the court specialization is restricted within the court of the first instance because the court of the second instance – the Civil Case department who is admissible to review the intellectual property disputes heard before the Riga Regional court, - reviews the cases in the body of three judges and already for this reason only it is more difficult to have certain specialization in this specific sphere.

f) Specialized protection means in the civil procedure

Based on the European Parliament and the Council Directive no 2004/48 EC dated April 29, 2004 on the enforcement requirements of intellectual property rights, important amendments were introduced under Chapter 16 of the Civil Procedure law (Providing of evidences) as well as a special new Chapter 30.2 (Cases on the intellectual property infringements and protection). According to these amendments, it is possible to decide about providing of evidences before the action is raised based on the application of the interested person to provide evidences to be reviewed by the court within 10 days from its receipt. Such procedure may even take place without invitation of the potential parties in urgent matters, also in urgent copyright and neighbouring right matters, database protection (sui generis), trademarks and geographical indications, patents, designs, plant varieties, infringements or possible infringements in semi-conductor topographies. By satisfying such application to secure evidences before filing the claim, the judge may require that the potential claimant, having paid a definite sum of money into the bailiff's deposit account or by filing equivalent guarantee, secures compensation of the damages that the respondent could incur due to securing evidences (Article 100 of the Civil Procedure law). Respondent may claim compensation of damages incurred due to securing of evidences if such securing is cancelled or if the action brought against it is dismissed, left without further hearing or proceedings suspended. While Chapter 30.2 provides several additional measures in the matters related to infringements and protection of intellectual property rights. One of such measures is temporary protection means. If there are grounds to assume that the rights of the intellectual property subject are infringed or could be infringed, the court, at the motivated request by the claimant, may adopt a ruling on the temporary protection means, namely – to rule about seizure of such movable property by which possibly the intellectual property rights are infringed, to set forth a duty to withdraw the goods by which possibly the intellectual property rights are infringed, to prohibit carry out certain activities both for the respondent and the persons whose services are used in order to infringe the intellectual property rights, or for the persons who make carrying out of such infringement possible (Article 250.10 of the Civil Procedure law). Such temporary protection means may be envisaged both before raising the action and also afterwards.

Before the action is brought to the court, the judge shall define a term to submit the claim that shall not exceed 30 days. The judge or the court shall decide about applying temporary protection means within 10 days as from receipt of the application or initiation of the proceedings. Temporary protection means are effective until the day when a judgment enters into force. This procedure is asymmetric as to the scope of the rights assigned to the parties. The applicant, whose application is dismissed, may appeal against the court's or a judge's decision while the respondent or even the potential respondent is not assigned with the rights to appeal the decision by which the temporary protection means have been applied against him. However, the respondent has the right to claim compensation for losses caused in the result of applying temporary protection means provided that the temporary protection means are cancelled or the raised action dismissed, left without further hearing or proceedings suspended.

The asymmetric division of the rights and obligation is also expressed in a way that by satisfying the application to apply the temporary protection means before the claim is raised, the court or the judge may oblige the claimant to ensure losses which might be incurred by the respondent or other persons against which such means may be applied by paying a definite sum of money into the bailiff's deposit account or ensuring equivalent guarantee. Yet prerogatives are not set forth regarding the application to apply temporary protection means submitted already after the claim is raised.

The mentioned amendments also provide broader prerogatives during the time when the judgment is made. If the infringement fact has been proved, the court may set forth several measures in the judgment that can be perceived as preparation for unlawful usage of the intellectual property rights, provide services used for unlawful activities with the objects of intellectual property rights as well as recall or fully withdraw from the market the counterfeit goods (counterfeit samples), destroy the counterfeit goods (counterfeit samples), recall or fully withdraw from the market or destroy devices and materials used or indented to be used for counterfeit goods (counterfeit samples) provided that their owner knew or should have known from the case circumstances that these devices and materials were used or indented to be used for unlawful activities as well as partially or fully make public the court's judgment in newspapers and other mass media.

3. "White areas" in legislation on intellectual property

With regard to several well known types of intellectual property like sui generis rights of databases, geographical indications and addresses or domain names, the legislation was not either drafted (domain names) or contained only very general statements (geographical indications).

Databases as an independent protection object are referred to in the Copyright law of 1993. Individually though this law only protects work collections, like encyclopaedias, anthologies and atlases as well as databases and other complied works that in terms of material selection and arrangement are the result of a creative work" ( Para 1 of Article 5 of the Copyright law).Thus based on this law the database protection was only possible on condition that, first, the data contained in the database shall be per se recognized as objects (works) of copyright, second, that their compilations is a result of a creative work. Consequently, databases lacking one or both mentioned features or the so called sui generis rights, were not protected according to this law. With regard to the ownership rights to the databases, the Latvian situation cannot be viewed as unique as it should be kept in mind that also in the EU to which Latvia joined only after ten years period since the first intellectual property rights were consolidated, these rights have fully developed only since 1991.19

A database is a special intellectual property rights object. The fact that in the legislation of some countries, including Latvia, the legal regulation of databases and copyright objects is comprised under one and the same regulatory act may not create a confusing view about any affinity between these two principally different protection objects. It is true however that historically the legal protection of databases has evolved organically from the mechanism for protecting literary works. It refers to compilations of literary and art works defined under Para 5 of Article 2 of the Berne Convention. Still there is a grounded opinion that within the development of information technologies, the copyright cannot any longer ensure adequate protection of contribution20.

Sui generis rights of databases may be owned both by physical and legal persons. With respect to the subject of rights, the term author" is not used, but instead the database creator". However, it is stated under Article 4 of Directive no 96/9 that "The author of a database shall be the natural person or group of natural persons who created the base or, where the legislation of the Member States so permits, the legal person designated as the rightholder by that legislation". Subparagraph 2 of the same Article states that: "Where collective works are recognized by the legislation of a Member State, the economic rights shall be owned by the person holding the copyright." While Subparagraph 3 of Article 4 says that "in respect of a database created by a group of natural persons jointly, the exclusive rights shall be owned jointly". The literature says that this norm causes confusion with respect to the ownership rights to databases.21 Article 4 of Database Directive no 96/9 is mystically silent" on the ownership rights to the databases which are not protected by copyrights.22

Considering the above described uncertainties, an important role should be then allocated to the Latvian national regulatory acts for the legal regulation of the databases. Nonetheless, the present Copyright law of 1999, although addresses these issues in difference from the law of 1993, still solves them in very fragmentary way.

Like Christopher Rees has sarcastically commented drafting of the Directive, the European Commission was not about to let the opportunity pass of digging another section of the trench around Fortress Europe.23 Still as it may be seen, the Directive faces certain difficulties, its implementation process has not always run successfully. Also the content of the Directive is very contradictory. For example, Article 4 which is in conflict with the context of the rest of the Directive about the database creator and which refers to the database author, shall be regarded as a clerical error according to the above quoted Mr. Rees.24 Analysis and critical evaluation process of Directive no 96/9 is still a topical question.25

Domain names developed in Latvia largely due to the absence of a regulatory basis. It would be difficult to support the thesis that exactly the lack of regulatory grounds has left a positive impact upon the development of this intellectual property type. Still the registration process of domain names has turned out to be incomparably more successful than, let's say, the patent development in Latvia. And exactly due to the lack of respective legal norms, the court has refused to satisfy a claim about protection of the domain names against the trademark rights registered later.26 Yet it is obvious that a gross law interpretation mistake on the basis of which such wrong court's ruling was adopted, may not serve as an argument in the dispute whether in Latvia exist the rights to a domain name to be a specific intellectual property type as such rights were not only established by several judgments adopted in WIPO international arbitration related to the domain names registered in Latvia, but also in foreign legal literature.27

Finally in the transitional period disappeared the rights to an image existing before. Rights to an image may be understood as rights to immunity of general overall impression. Latvian legislation is also slightly familiar with protection of personality rights, although it has been noted that this protection mechanism is insufficient.28 Yet the image rights as the rights to the intellectual property are not either regulated or protected, though the literature has erroneously noted that such rights have never existed in Latvia.29 These rights were provided by the Latvian SSR Civil Code effective since 1964-1993 although this legal act, like the Society legal system in general, was not familiar with the intellectual property concept. Article 537 of the Civil Code envisaged interest protection of a citizen portrayed in fine arts work" stating that publishing, portraying and distribution of a fine arts work reflecting another person is allowed only by the consent of the reflected person, but after his/her death – by the consent of his/her children or a living spouse; afterwards there was a characteristic remark though: "Such consent is not required if it is done in the interests of the state or the public". According to the current legislation the image rights are protected so that in the result of their infringement the caused moral damage shall be compensated based on general norms on the damage compensation, especially based on the amendments introduced to Article 1635 of the Civil law.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.