I. INTRODUCTION

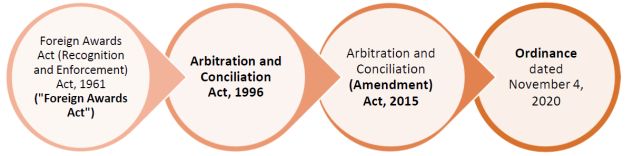

The enforceability of international arbitral awards in India has been structured and interpreted, over the years, to facilitate a pro-business, pro-arbitration climate in India, and attract international investments into the country. This note attempts to capture the legal framework in India for the enforceability of foreign arbitral awards, based on the fundamental principle of minimal judicial intervention. The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 ("Act") is the primary legislation that recognises the enforceability of foreign arbitration awards in India. A brief overview of the legislative history in this regard is provided below.

The jurisprudence on the enforceability of foreign awards can be traced back to the Act's predecessor, the Foreign Awards Act, and court judgments made under this legislation. The position of law on this topic has been further refined by way of amendments made to the Act in 2015, and by an ordinance passed on November 4, 2020 ("Ordinance"). This research note aims to trace the development of Indian jurisprudence concerning the question of enforceability of foreign arbitral awards, delving specifically into the context of the "public policy" standard applied to all arbitral awards, and to highlight recent changes in this regard.

II. REGULATORY SHIFT

The interpretation around the enforceability of a foreign arbitral award has witnessed a regulatory shift from the Foreign Awards Act to the Act as under:

Position Under The Foreign Awards Act, 1961

The Foreign Awards Act was enacted to give effect to the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards 1958 (the "New York Convention"), which aimed to ensure the enforcement of arbitral awards worldwide, given the growing importance of settling international and cross border commercial disputes in a binding manner. Under the Foreign Awards Act, all foreign awards were enforceable in India, and Indian courts had the ability to deny such enforcement only under certain specific conditions1. These conditions are discussed in more detail under the Act, below.

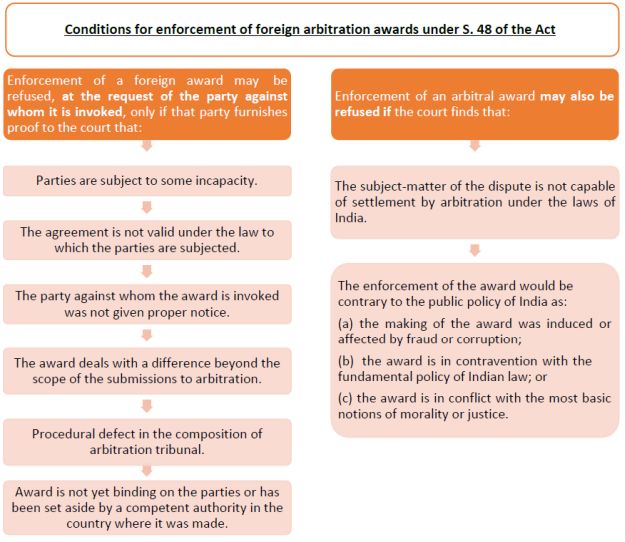

These conditions included, briefly – incapacity of parties to the arbitration agreement, lack of proper notice to parties, award dealing with matters beyond the scope contemplated for arbitration, procedural defect in tribunal composition and finally, where the award was not yet binding on parties or had been set aside by a competent authority in the jurisdiction in which the agreement was made. These conditions persevere mutatis mutandi in Section 48 of the Act (applicable to awards under the New York Convention) as it stands today.

In addition to the several determinable grounds discussed above, that may disqualify an award from being enforced in India, another more subjective ground was in instances where the court felt that the award, if enforced, would be contrary to public policy. A similar restriction continues in the Act today, under both Sections 48 and 57 – allowing Indian courts to deny the enforcement of foreign awards made under the New York Convention and the Geneva Convention2, respectively, if it is felt that the award would be contrary to public policy. As a result, both the term public policy, and what in essence constitutes "Indian public policy", has been heavily debated over the decades, in the context of the enforceability of arbitral awards that are made outside the territory of India.

The Renusagar Judgment (1994)

While public policy was not defined under the Foreign Awards Act, the jurisprudence around 'public policy' was established through a series of judgments by various courts. Most significantly, in the landmark case of Renusagar Power Company Limited v General Electric Co3 ("Renusagar"), the courts laid down a narrow interpretation of 'public policy', by establishing the principle that for an award to be unenforceable in India, it must cause a violation of public policy under Indian laws and not just under any law (including the applicable law in the jurisdiction in which the agreement, or award, was made).

In the Renusagar case, the Indian Supreme Court further determined that an award would violate Indian public policy, if its enforcement would be contrary to (i) a fundamental policy of Indian law; (ii) the interests of India; or (iii) justice or morality. The Court rejected Renusagar's contention that the award or interest was excessive or unjust, and ruled therefore, that enforcing the award would not be contrary to India's public policy.

Position Under The Arbitration And Conciliation Act, 1996

The Foreign Awards Act was followed by the enactment of the current legislation, namely the Arbitration and Conciliation Act 1996 (the Act). Part II of the Act deals with the manner of enforceability of certain foreign arbitration awards, namely awards made under the New York and Geneva Conventions. Under the Act, as under its predecessor, foreign arbitration awards are enforceable in Indian courts subject to certain conditions, which are set out under Sections 48 and Section 57 of the Act.

The Act further clarifies that after a court in India is satisfied that the foreign award is enforceable, the award shall be deemed to be a decree of that Indian court and the procedure for execution of decree under the Civil Procedure Code4 shall be initiated.

Arbitration And Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015

The 2015 amendment to the Act effected a couple of key changes, in relation to the regulation of foreign arbitral awards in India, and the interpretation surrounding their enforceability.

Firstly, and most importantly, in the context of our discussion, the 2015 amendment added explanatory language to multiple sections of the Act5 in order to clarify the specific meaning of the term 'public policy', and consequently, which foreign awards would be considered unenforceable on the ground that the award in question was in conflict with the public policy of India.

Per the inserted explanation, an award would be deemed to be in conflict with the public policy of India, only if - (i) the making of the award was induced or affected by fraud or corruption; (ii) the award was in contravention with the fundamental policy of Indian law; or (iii) the award was in conflict with the most basic notions of morality or justice. This would be applicable to both domestic and foreign arbitral awards, under the Act.

Secondly, under Section 34 (Setting Aside an Arbitral Award), the 2015 amendment further clarified that the ground of 'patent illegality' to challenge an award may only be taken for domestic arbitrations6 and that this provision excludes international commercial arbitrations from its purview. Under the relevant provision, domestic awards may be set aside under Section 34 for patent illegality, but not for erroneous application of the law or for the reappreciation of evidence. At the risk of repetition, this provision would not be applicable to foreign arbitral awards.

In fact, the Supreme Court had clarified the reasoning behind this statutory interpretation, before the 2015 amendment, in the Shri Lal Mahal v. Progetto Grano Spa case7. The court stated that the patent illegality test could not apply to foreign awards since Indian courts neither exercise appellate jurisdiction over the foreign awards nor scrutinize the process under which such foreign award was rendered8. Additionally, the Supreme Court reiterated the (Renusagar) position of law that for a foreign award to be unenforceable in India on the grounds of being contrary to public policy, it should be contrary to the (i) fundamental policy of Indian law; (ii) interests of India; or (iii) justice or morality9.

In effect, the principle laid down in the Renusagar test had become the applicable standard for checking the enforceability of foreign awards. And, after the 2015 amendment, this is now the settled position of the law, as far as statutory interpretation of the term public policy is concerned.

Interpreting "Public Policy" After 2015

In recent years, following the 2015 amendment, several cases before the courts have highlighted the various submissions made in relation to what constitutes a contravention of India's "public policy", and hence what would qualify as valid grounds for refusal to enforce foreign arbitral awards before the Indian courts.

In Campos Brothers Farm v. Matru Bhumi Supply Chain10, the Supreme Court refused to enforce a foreign arbitral award, as in its view, the procedure the respondents were subjected to violated principles of natural justice. First, by denying them the opportunity to make their submissions known to the sole arbitrator appointed to resolve the dispute – namely the right to a fair hearing. And second, due to the marked absence of a speaking order – i.e., by the sole arbitrator omitting to provide any substantive reasoning for their final decision.11 In another recent case12, the courts, in dealing with the question of enforceability of foreign arbitration awards, held that if the award is ex facie illegal, and in contravention with the fundamental law of the land, then the enforcement of such an award would also be violative of the public policy of India.

Interlocutory Arbitral Orders: Enforceable Or Not?

A strict interpretation of the Act would indicate that interim arbitral orders passed abroad, by emergency arbitrators, are not recognised under the current legislation. That said, an interesting and recent development in Indian arbitral jurisprudence, relates to Reliance Retail's open defiance of the interim order passed by an emergency arbitrator in an arbitration initiated by Amazon.com Inc ("Amazon") against certain entities in the Future Group ("Amazon Case"), before the Singapore International Arbitration Centre ("SIAC").

While this conflict is still picking momentum, there is a clear winner in terms of next steps – Amazon has successfully procured an Emergency Arbitration order ("EA order"), and must now determine how best to ensure the EA order of SIAC is enforced against the Future Group in India.

Further, the Delhi High Court has recently13 passed an order confirming the award passed by SIAC holding that the EA order passed by SIAC was not a nullity as alleged by Future Retail and that it was enforceable under the Indian law. The Court also directed the parties to maintain status quo on the issue, against which order Future Retail has appealed to the division bench. It is also interesting to note that the scheme of arrangement between Reliance and Future groups had already received approval from the Competition Commission of India (CCI) with no objection from Securities Board of India (SEBI).

The Amazon Case has gained traction due to both the size of the conglomerates involved, as well as the dire lack of jurisprudence around the enforcement of interlocutory or interim arbitral orders under the New York Convention, in foreign jurisdictions. As a strategic decision, Amazon representatives sought to have the order passed by the emergency arbitrator sitting at SIAC, and followed this by enforcing it in a commercial court in India under the Civil Procedure. This arguably puts them in a better position than they would be if they followed the duplicative approach of initiating a petition under Section 9 of the Act. Such an outcome is perceived as efficient decision-making as well, considering that only a satisfactory nod is required by the Indian courts to suggest that the order or judgement passed by a foreign court is fair and judicious. It will be very interesting to see how things pan out, in the Amazon Case, in the weeks and months to come.

III. ORDINANCE 2020

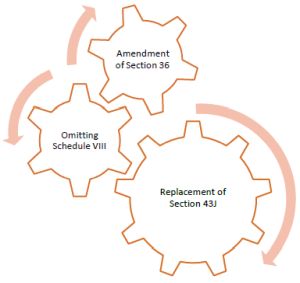

A. Unconditional Stay On Domestic Arbitral Awards

Section 36 of the Act lays down the provisions pertaining to enforcement of the arbitral award. The intent behind the introduction of the Ordinance is to ensure that all the stakeholders get an opportunity to seek the unconditional stay of enforcement of arbitral awards, where the underlying arbitration agreement, or making of the arbitral award, was induced by fraud or corruption. The Ordinance has elaborated on the power of the courts to stay any such arbitral awards where the underlying arbitration agreement or making of award are induced by fraud or corruption. It clarifies and extends the applicability of this provision to all court cases arising out of or concerning arbitral proceedings, irrespective of whether the arbitral or court proceedings were commenced before or after the commencement of the Arbitration and Conciliation (Amendment) Act, 2015.

The question of law that triggered this move was the interpretation of the term "serious allegation of fraud" for which the court laid down two working tests to determine whether a case qualifies to be assessed as one of a serious allegation of fraud14. The first test is if the fraud itself permeates the entire contract which envisages arbitration, including permeating the agreement to submit to arbitration - in which case, this would qualify as a serious allegation of fraud. The second test operates in a manner to exclude simple allegations of fraud – i.e., is if the allegations of fraud touch upon the internal affairs of the parties between themselves, and thus have no implication in the public domain, this would make the alleged fraud a "simple allegation of fraud", distinct from the above mentioned serious allegations.

The Act empowers Indian courts to stay the enforcement of domestic arbitral award if thought to be fit and the reasons are recorded in writing15. Interestingly, the Ordinance specifically makes an addition to the existing provision and makes us wonder whether the new language is to be interpreted in a restrictive sense. We infer, from this additional qualifying language added by the Ordinance, that it shall be up to the courts to interpret whether their powers have been limited to granting an unconditional stay only if the award is based on an agreement induced by fraud or corruption.

B. Qualifications Of Arbitrators & Omission Of Schedule VIII Of The Act

Additionally, the Ordinance also replaces the language in Section 43J of the Act which originally referred to Schedule VIII of the Act for the qualifications, experience, and norms for accreditation of arbitrators. The Act has now been amended to refer to the "regulations for the norms of accreditation", and Schedule VIII has been done away with. The Ordinance is silent on the specifics of which regulations are to be followed for the purpose of Section 43J. This clause initially expressly barred foreign arbitrators from participating in arbitrations in India, however, the pendency of the new accreditation regulations leaves scope for speculation on whether there will be a formal inclusion of the foreign arbitrators in the Indian arbitration framework, given the deletion of Schedule VIII from the Act, in its entirety.

Schedule VIII has been deleted from the Act, which dealt with the qualifications and experience of the arbitrator. This change will be very welcome, if it acts to removes barriers to the appointment of foreign qualified judges and lawyers to act as arbitrators in India. This deletion also results in the removal of prerequisites for the appointment of domestic arbitrators - such as the requirement for an arbitrator (i) to have prior legal experience; (ii) to possess certain qualifications; or (iii) for the arbitrator be enrolled as an advocate with the courts of India. Accreditation regulations are expected soon, but in the meanwhile, this new scheme could very well facilitate the onboarding of various subject matter experts in their respective domains to share their technical knowledge in the process of arbitration.

IV. CONCLUSION

From the provisions of the Act, and various judicial pronouncements over the years, it is understood that foreign arbitral awards are enforceable in the courts of India subject to the limitations under Section 48 and Section 57. The Ordinance is intended to evolve the law, and broaden the fundamental principle behind the enforcement of foreign arbitral awards in India, which is the promise of minimal judicial intervention, and of some comfort regarding ease and certainty of business activities. We are yet to see the impact of this Ordinance, and how it is to be received in the market, however it appears to be a step in the right direction, by acting to make the arbitration process both more flexible as well as more effective, as a form of alternate dispute resolution.

Footnotes

1. See S. 7 of the Foreign Awards (Recognition and Enforcement) Act, 1961.

2. The Geneva Protocol on Arbitration Clauses of 1923

3. AIR 1994 SC 860, Interpreted section 7(1)(b)(ii) of the Foreign Awards Act

4. Order 20 of the Civil Procedure Code, 1908

5. Section 34, 48, and 57 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

6. This was specifically and recently reiterated in Patel Engineering Limited v. North Eastern Electric Power Corporation Limited, SLP Nos. 3584-85 of 2020

7. Shri Lal Mahal v. Progetto Grano Spa (2014) 2 SCC 433

8. Ibid.

9. Section 48(2)(b) of the Act

10. Campos Brothers Farm v. Matru Bhumi Supply Chain Pvt. Limited and Ors, (2019) 261 DLT 201

11. Ibid.

12. National Agricultural Co-Operative Marketing Federation of India v. Alimenta S.A., MANU/SC/0382/2020

13. See https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-why-is-the-delhi-hc-order-on-future-group-amazon-dispute-important-7173203/ (last accessed Feb 17, 2021)

14. Avitel Post Studioz Limited v. HSBC PI Holdings (Mauritius) Limited Civil Appeal No. 9820 of 2016

15. Section 36(3) of the Act

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.