October has been a very busy month for the Indonesian government. Besides issuing the implementing regulation on Language Law and new regulations on upstream data management and data localisation requirement, the government also enacted a new law on water resources1 ("2019 Law"), which replaced the previous Law No. 11 of 1974 on Irrigation ("1974 Law"). Judging from the length of time between the old law and the new law, many would say this law is long overdue.

The 1974 Law itself was revived in 2015 when the Constitutional Court2 annulled a 2004 law governing utilisation of water resources ("2004 Law").3 In its ruling, the Constitutional Court found that the 2004 Law have failed to accommodate the state's role in controlling and managing water for public interest, as mandated under the 1945 Constitution. Following this ruling, the government also enacted two implementing regulations containing practical rules that the industry desperately needs, which were not facilitated by the grossly outdated 1974 Law.4

Our discussion below will be centred around key points in the 2019 Law and most importantly, how it seeks to accommodate the issues addressed in the 2015 Constitutional Court's decision.

Affirmation of State Control

The 2019 Law explicitly states that water resources must be controlled by the state and used for the utmost prosperity of the community. Therefore, individuals, community groups or business entities cannot possess or control water resources, and control remains with the central and regional governments. It further emphasizes that society's right to water as guaranteed by the state is not to be interpreted as a title over water resources, but rather a right to receive and use water.

By doing so, the state is responsible for the conservation, sustainable utilisation and management of potential damage to water resources. This is reflected in its duties and obligations, which include the authorities to:

- issue water utilisation permits for commercial and non-commercial purposes;

- determine and collect water tariffs;5 and

- determine river-regions and adopt management outlines and plans over water resources based on river-regions.6

Assignment to Government-Owned Enterprises

Interestingly, the central and regional governments can assign some of their duties and authorities, including collecting water tariffs from license holders within a specific working area, to a state-owned or regional government-owned enterprise specifically established to carry out some of the government's role to control water resources.

Meanwhile, in the regional level, the existing regional government-owned enterprises can only deal with drinking water supply system. Other than that, the central government, i.e. the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, directly manages 128 river-regions through 34 technical agencies.

Priority on Water Utilisation

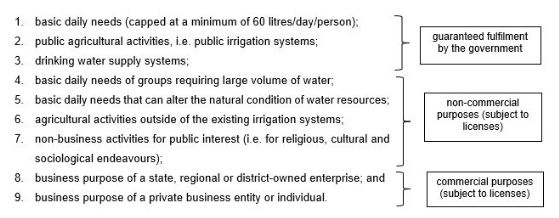

Different from the management of water resources, which is an innate control of the government (assignable to government-owned enterprises), anyone can apply for a license to utilise water resources for various purposes, either commercial or non-commercial. The 2019 Law prescribes a clear hierarchy of water utilisation that must be observed:

As we can see from the hierarchy, water utilisation for a specific purpose can only be done if the purpose listed above it has been fulfilled. Utilisations for non-business activities and business purposes are on the bottom of the list and as such, entities can only use water for these purposes if water for the public's basic daily needs and agricultural activities have been fulfilled.

This is a significant breakthrough not only because it conforms with the principles mandated under the 1945 Constitution, but also because it eliminated any doubt about priority of water utilisation.

Licenses

The 2019 Law also introduces a licensing regime that requires everyone to obtain licenses from the government to use water for non-commercial activities and business purposes outside of those main daily needs whose fulfilment are guaranteed by the government.

There are two types of licenses that can be issued, namely licenses for non-commercial activities and licenses for commercial purposes. For the latter, licenses would only be granted if the following conditions are met:

- there is no harm to the public's interest over water resources;

- state's protection over the public's right of water resources are ensured;

- water resources utilisation is environmentally sustainable;

- the state retains absolute supervision and control over the water resources; and

- priority is given to the commercial purpose of a state-owned entity.

This licensing regime reaffirms the 2015 Constitutional Court's ruling, where private entities can only use water for commercial purposes if certain requirements have been complied with. The procedure to obtain licenses will be detailed in an implementing regulation.7 All licenses issued prior to the enactment of the 2019 Law remain valid, while all applications for licenses submitted prior to the enactment of this 2019 Law will be processed pursuant to the 2019 Law.

Again, priority is to be given to state-owned entities. Private entities may apply for a license if it complies with the water resources management outlines and plans8 and certain administrative technical requirements, in addition to obtaining approval from relevant stakeholders within the area where the water resources are located. In cases where a river-region has been assigned to a state-owned enterprise as its working area, private entities must cooperate and pay the water tariffs to such state-owned enterprise. This means that where a private entity wishes to utilise water for a commercial purpose, e.g. for hydro power plant, the private entity must not only obtain a license from the government, but also enter into a contract with the state-owned enterprise who controls the management of the relevant river-region area.

Questions Remain for Drinking Water Sector

The government currently regulates the drinking water sector through a government regulation,9 which only allows the private sector to participate by way of investing and managing raw water units and production units (i.e. water intake facilities and water treatment plants), as well as investment in the water distribution facilities.

The operation of the water distribution facilities up to delivery points to end consumers remains exclusively reserved for state-owned or regional government-owned entities. As the implementing regulation for the 2019 Law is still pending, it is currently unclear whether private entities will enjoy an expanded scope of business.

In any event, where the raw water unit and production unit of a private entity is located within a river-region that has been assigned to a certain state-owned enterprise, such private entity would need to enter into cooperation with two different entities, namely the regional government-owned entity managing the drinking water system in such region, as well as the state-owned entity authorised to manage water resources and collect water tariffs in the location where the private entity's units are located. Further, the private entity will need to consider the permitted water volume intake from the state-owned entity in that location and the processed water volume to be supplied to its regional government-owned offtaker.

Conclusion

Besides filling in the legal vacuum and recognising water as an important commodity, in line with the 1945 Constitution, Law 2019 is also a bold move by the government in terms of maintaining control and regulating private sector's participation.

The 2019 Law attempts to strike a balance between public and private interest by, among others, giving the public the first priority in access to water sources. In contrast, the private sector has the last priority, in addition to having to obtain licenses, fulfil certain administrative requirements and enter into contract with state-owned enterprise. Private sector engaged in drinking water supply system business must also enter into a contract with the regional government-owned enterprise in charge of the drinking water supply system in the area.

Despite the regulatory hurdles, there is still a role, and indeed, our view is that the government is still keen on private sector's participation in this industry. But such participation will depend on the right mould and arrangement (i.e. BOT). On top of that, the licensing regime under the 2019 Law may change the way licenses are given in this industry. We can only hope that both topics would be detailed in the implementing regulation.

There is also a lack of clarity in situations where the government assigns water management in a working area to state-owned or regional government entities. What is their level of power and how far can they exercise discretion in implementing the management outlines and plans determined by the government? For instance, can they determine the number of potential commercial uses in in one river-region, e.g. two hydro power plants, three drinking water supply system, etc., based on water volume availability, or does the government retain the authority to determine types of utilisation?

Lastly, it is important that we put this discussion into context. So far, Indonesia has suffered from unequal water distribution across its regions, marked with overexploitation in some areas in contrast to abundant supply in other areas. Further, the general public still lacks access to clean water. While the government can assert that the 2019 Law ensures public access to water, the fundamental question remains: does the government have the resources and capacity to effectively manage water for the public good?

Footnotes

1 Law No. 17 of 2019 on Water Resources.

2 Constitutional Court Decision No. 85/PUU-XI/2013, dated 18 February 2015.

3 Law No. 7 of 2004 on Water Resources.

4 Government Regulation No. 121 of 2015 on Commercialisation of Water Resources and Government Regulation No. 122 of 2015 on Drinking Water Supply System.

5 Water tariffs under the 2019 Law, or Biaya Jasa Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Air, are collected as fees for the management of water resources. This is a different tariff from the currently prevailing groundwater tax.

6 The 2019 Law covers all water above and below ground, inter alia, surface water, groundwater, rainwater, and sea water that is contained within a land. Rivers, as the biggest water resources under this definition, are governed based on their regions, which are reflected in management outlines (Pola Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Air) and management plans (Rencana Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Air).

7 Law 2019 mandates the enactment of government regulations that will update/replace the currently prevailing regulations on commercialisation of water resources and drinking water supply system.

8 Water resources management outlines (Pola Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Air) and management plans (Rencana Pengelolaan Sumber Daya Air) as determined by the central government or regional government, as relevant.

9 Government Regulation No. 122 of 2015 on Drinking Water Supply System.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.