The present paper discusses global financial standards and their relevance as part of the regulatory reforms initiated in the aftermath of the financial turmoil. In a first – precursory – part, it provides more clarity on the notion and role of "soft" law instruments, which have become an eminent pillar for the regulation of global finance. The essay likewise highlights the financial sector specific division of labor between the different international bodies, fora, and organizations in charge of global agenda-/standard setting. In the main – analytical – part, the article will turn to the sweeping reforms triggered by the experiences in the financial crisis. Emphasis is put on standards aimed at preventing systemic risk in the field of capital adequacy, prudential supervision, and accounting. The analysis of the reform efforts reveals specific deficiencies, which raise doubts as to their effectiveness to deal with a crisis comparable to the one in 2008 et seqq. In the final – concluding – chapter, the key findings for the study of global financial standard setting and crisis reforms will be briefly summarized.

I. Introduction

1. Global regulatory reform and standard Setting

Since the global financial crisis, bold steps have been undertaken to reform the global financial system and the regulatory framework. Amongst the most important regulatory reform focus areas was a strengthening of capital requirements and the introduction of both liquidity standards and a leverage ratio requirement for international banks, which were recognized by the Group of 20 (G20) upon proposal by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) during the Summit in Seoul (2010). This has been complemented by a tightening of prudential supervisory standards issued by the BCBS. Moreover, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) has embraced new accounting principles that aim to inhibit financial instability in falling markets. Other areas of reform range from improving the regulation of overthe- counter (OTC) derivatives or advanced standards addressing credit rating agencies (CRA) to the measures taken to tackle the risks posed by "Systematically Important Financial Institutions" – the list could easily be expanded.1 Additionally, there was a broad consensus among political leaders that a more intensified international cooperation and coordination of regulatory efforts was indispensable so as to ensure consistent formulation and implementation of reforms.2 It was stressed that the strengthening of global financial standards (GFS) and their consistent implementation is necessary to protect against adverse cross-border, regional and global developments affecting financial stability.3

The present paper examines GFS and the endeavors of the international regulatory community to prevent cross-border systemic risk and financial instability. At the outset, the main features of GFS as well as the actors and processes relevant to global agenda-/standard setting are briefly illustrated (I). The main part provides an overview of the international regulatory responses following the financial crisis (II) and outlines critical considerations regarding the global reforms (III). Finally, the key conclusions and insights will be summarized (IV).

2. "Soft law" standards in financial law

Global financial standards can be defined as the minimum requirements applied globally to prevent systemic risk.4 The most well-known GFS are the Basel Committee's capital adequacy standards, which will require banks to hold minimum common equity tier one capital (primarily common shares and retained earnings) in the amount of 7% of their assets.5 GFS may come in various phenotypes – depending on their specificity – as good principles, practices, or guidelines and can be categorized by their scope in either functional or sectoral standards.6 From the legal viewpoint, global financial standards per se are not binding, i.e. they do not qualify as a source of public international law (under Art. 38 ICJ-Statute).7

As a consequence, neither the regulatory reform agenda nor related standards can be enforced through courts. Instead, the GFS belong to the category of rules, which it has become customary to designate as soft law.8 In the most basic sense the term "soft law" refers to international promises, obligations, or commitments that are not binding under international law. More specifically, soft law standards have been defined as "international obligations that, while not legally binding themselves, are created with the expectation that they will be given some indirect legal effect through related binding obligations under either international or domestic law."9

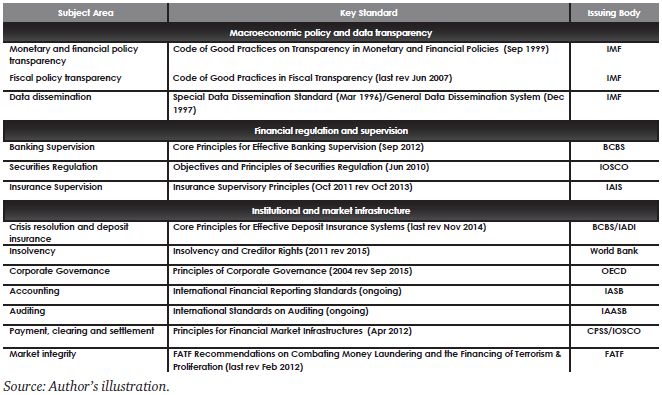

To help shed light on the thicket of standards, the FSB has designated 14 GFS under 12 policy areas as "key" for sound financial systems and indicated that those standards are most likely to make the greatest contribution to reducing vulnerabilities and strengthening the resilience of financial systems. The FSB list of key standards encompasses standards in areas as disparate as monetary and financial policy, fiscal transparency, data dissemination, banking supervision, securities regulation and insurance supervision, insolvency, corporate governance, accounting, auditing, payment and settlement, and market integrity. The FSB list of key standards wholly coincides with the IMF and World Bank endorsement of internationally recognized standards.

However, it is important to note that the "soft" legal character does not necessarily affect the effectiveness of GFS as the various jurisdictions may well be (and indeed often have been) persuaded to incorporate these standards into their domestic legislative and regulatory frameworks either as a matter of selfinterest or bolstered through other mechanisms.10 In fact, markets may have a function in disciplining national regulatory compliance. This is due to the fact that financial firms domiciled in countries that do not adhere to GFS may have to pay a risk premium when refinancing at the capital markets. Additionally, states, international organizations, International Financial Institutions (IFIs) and regulatory networks have set up various structures and arrangements of a more institutionalized nature, which they apply to discipline national compliance. Examples include peer review mechanisms, loan conditionality, market access restrictions, or IFI monitoring programs.11

As one can infer from the table below, various GFS have undergone revisions in the aftermath of the crisis reflecting some of their perceived deficiencies.

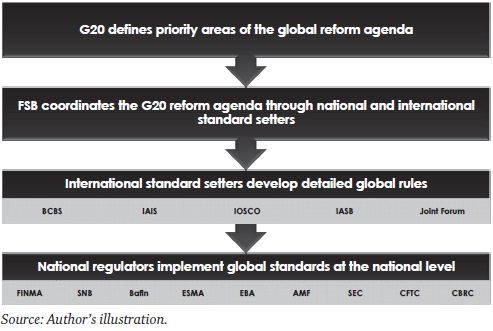

3. The agenda-/standard setting process

The global agenda-/standard setting process relies on a multi-level structure.12 At the first – top – level there is agenda setting, a process primarily carried out by the G20. This rather political gathering is the prime forum for cooperation on reform of the global financial system at the head of state level. In practice, the G20 specifies the regulatory reform agenda in particular areas where reform is most needed, e.g. OTC derivatives reforms or banking capital requirements. Also at the top level, the Financial Stability Board (FSB), a semi-political body, amongst others made up of finance ministry officials and central bank governors is responsible for coordinating national and international standard-setters in the transposition of the regulatory reform agenda. Aptly both bodies have been termed the "soft decision-making bodies" for financial regulatory reform.13

At the second – medium – level is standard setting. This level entails the specific regulatory groundwork of negotiating and developing of GFS based on the regulatory reform agenda provided by the G20. Concretization through more detailed guidance is necessary because the G20's agenda presettings are mostly rather broadly formulated. The standard-setting bodies are therefore promulgating more specific guidance, which is then made available for national implementation. More specifically, GFS for the banking sector are worked out by the BCBS, a forum for banking supervisory cooperation made up of central bank governors. GFS for the insurance sector are worked out by the IAIS, an organization of insurance supervisors and regulators. Moreover, GFS for the se- curities sector are developed by IOSCO, an association of organizations that regulate the world's securities and futures markets. Contrary to international organizations, all of these institutions are informally structured.14

At the third – lower – level is the domestic implementation of GFS. National legislators and regulatory authorities are supposed to adjust their local legal and regulatory frameworks on the basis of the GFS that have been adopted at the level of the interna- tional standard setters. National implementation efforts are overseen by the IFIs, which have set up monitoring (or "surveillance") programs, such as the Financial Sector Assessment Program and the related Reports on the Observance of Standards and Codes. IFIs play only a minor, supporting role in developing regulatory standards for the international financial markets but their monitoring programs have a global outreach.

To continue reading this article, please click here

Footnotes

1 For a high-level overview see Nicolas Véron, The G20 Financial Reform Agenda After Five Years, Bruegel Policy Contribution, 11 (2014), 4 et seqq., available at:http://bruegel.org/publications/ .

2 Ex multis G20, Declaration on Strengthening the Financial System, London (2 April 2009), Preamble, 1.

3 Ex multis G20, Leaders Declaration, Los Cabos (18/ 19 June 2012), n. 36.

4 Cf. Mario Giovanoli, The Reform of the International Financial Architecture, International Law and Politics, 42 (2009), 81–123, 84.

5 Cf. BCBS, Basel III: A global regulatory framework for more resilient banks and banking systems (December 2010, rev June 2011), 13, 54, available at:http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf .

6 See Financial Stability Board, What are standards?, available at:http://www.fsb.org/cos/standards.htm .

7 See Vera Schreiber, International Standards – Neues Recht für die Weltmärkte?, Bern (2005), 95.

8 See Peter Nobel, Finanzmarktrecht: Neue Architektur – Neuer Wein?, BJM 3 (2015), 129–153, 137 et seq.

9 Arie C. Eernisse, Banking on Cooperation: The Role of the G-20 in Improving the International Financial Architecture, Duke Journal of Comparative and International Law 22 (2012), 239–266, 250.

10 E.g. The People's Republic of China's latest decision to adopt the IMF's data dissemination standards, cf. Reuters, China changes GDP data calculation method to improve accuracy (9 September 2015), available at: http://www.reuters.com/article/china-economy-data-gdp-idUSL4N11F1V220150909 ; see generally Nina Arquint, Internationalisierung der Finanz marktaufsicht, GesKR 2 (2014), 131–142, 132.

11 For a thorough review of these mechanisms see Stefan A. Wandel, International Regulatory Cooperation: An Analy- sis of Standard Setting in Financial Law, Zurich (2014), 108, 117 et seqq.

12 See ibid., at 70 et seqq. for a more detailed discourse and further references.

13 Rolf H. Weber, Legitimacy of the G20 as a Global Financial Regulator, Banking and Finance Law Review (2013), 389–407, 390.

Previously published in Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Wirtschafts- und Finanzmarktrecht SZW, 06/2015, 562-569.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.