The Mauritius/India Double Tax Treaty (without Tears)

This article was originally published in January 2008 but has been updated in August 2009.

Introduction

Almost by definition, the experienced offshore practitioner has to be proficient (if not always an expert) in all manner of legal, accounting, taxation, regulatory and general business matters. That is to say nothing of being a mentor, confidante and sometimes psychologist to one's clients. As one of those non-tax experts, formerly working in non-tax treaty jurisdictions, the role of the Double Tax Avoidance Treaty in international operations has for me, over thirty or so years, been largely something for others to worry about.

I will not take up the reader's time unduly by explaining all of the academic, macro-economic, philosophical and geo-political reasons behind Double Tax Agreements ("DTA's") in general. Suffice it to say however, that without them, the imposition of taxes in both the home country of the principal and in the place where the income arises, without any relief, would be less than helpful to the success of international trade and would undoubtedly encourage less legitimate means of reducing this particular financial overhead for those involved.

A Little Bit of History

In the case of the treaty negotiated between India and Mauritius, it seems that what started out in 1983 to be a leg-up for Indian businesses wanting to ply their trade in other countries in the region, turned soon thereafter into an ideal (and much larger) vehicle for entrepreneurs from outside India to avoid double taxation upon their investments made into that country. It is arguably due to the genesis of this treaty that it was then, and remains to this day the most advantageous of all of the DTA's with India.

Over the last two decades, as a result of liberalised fiscal and investment policies, India has stood witness to record GDP growth rates, flourishing services and manufacturing sectors, an exponential rise in foreign direct investment. As a consequence, Mauritius has secured a prominent slot in the tax treaty planning of private equity players, MNCs and global funds. Even in the times of crisis, India is targeting a growth rate of 5 to 6%.

That is not to say that there have been no challenges and changes along the way. In 2003 the Indian Government withdrew the ability of Non Resident Indians to hold their personal portfolios of Indian quoted investments through private Mauritius Companies. The 2004 Indian budget withdrew withholding tax on dividends paid and abolished capital gains tax on certain transactions. But as we shall see, substantial opportunities still exist.

So, who has been investing in India in recent years? The following table shows the volume and sources of funds of Foreign Direct Investment ("FDI") for the entire period April 2000 to May 2009.

SHARE OF TOP INVESTING COUNTRIES - FDI INFLOWS (US$ Millions)

|

Rank |

Country |

Total 2000 to 2009 |

% of Total of all Countries |

|

1. |

Mauritius |

39,379 |

44 |

|

2. |

Singapore |

8,071 |

9 |

|

3. |

U.S.A |

6,508 |

7 |

|

4. |

U.K |

5,289 |

6 |

|

5. |

Netherlands |

3,701 |

4 |

|

5. |

Cyprus |

2,579 |

3 |

|

6. |

Germany |

2,379 |

3 |

|

7. |

France |

1,233 |

1 |

|

8 |

UAE |

995 |

1 |

Mauritius remained the largest source of foreign investment in India, contributing USD 39 bn in FDI inflows during the period April 00 to May 09, representing 44% share of total flows.

Mauritius has a small number of well heeled residents but they are

certainly not the source. Part of the answer lies in the use of the

Category 1 Global Business Licence companies ("GBL1")

incorporated in Mauritius and which will have been the conduit for

all these investments. It is these entities that make use of the

1983 DTA (and some of the other 34 such treaties with Mauritius)

and by so doing reduce their overall tax bill in the process.

As to why for example, those US investors of nearly US$ 6.5 billion over the period were not using this jurisdiction might seem a mystery. As will be seen, the taxation effect of not doing so could be seriously detrimental to their financial health. It might be the case therefore that the investments were directed into listed securities on an Indian Stock Exchange and for long term investment. In such cases, the taxation on the eventual gains is the same both inside and outside the treaty. Additionally, some of the investments may have been Government to Government which again would not have any taxation implications. On the other hand, there is certainly plenty of anecdotal evidence to suggest that the possible avoidance of CGT in India by using the Mauritius GBL 1 is simply off the radar of many uninitiated advisers. Hopefully this article might land on the desk of one such person in due course.

India no longer charges a withholding tax on dividends declared by an Indian company. They are thus tax exempt in the hands of the shareholders although the Indian company itself will be required to pay a dividend distribution tax at the rate of 16.995% (inclusive of surcharge and education excess) on such dividends. Consequently, provided that dividend withholding tax is not reintroduced in India, the use of the treaty would appear at first glance to be of no beneficial eff

ect to the investor. He can remit his Indian dividends to his home country and pay local taxes upon the gross dividend received.

However, a large proportion of the US$ 94 billion invested over the last 9 years will have been with a view to making capital gains (and very often from unlisted securities), rather than securing a regular dividend flow. Set out below is a table which gives the rate of Indian CGT applicable under various circumstances.

INDIAN CAPITAL GAINS TAX RATES

|

Long Term Gains1 |

Short term Gains2 |

||||

|

Listed (a)3 |

Listed (b)4 |

Unlisted |

Listed |

Unlisted |

|

|

Non-Resident Individual |

0% |

15% |

20% |

15% |

30% |

|

Non-Resident Corporation |

0% |

15% |

20% |

15% |

40% |

Many of the venture capital, private equity, real estate development and BPO investments made (whether through private equity funds or directly) are via unlisted securities in India. It perhaps comes as no surprise to hear therefore that a Mauritius GBL1 company, fully compliant with the treaty requirements, pays no capital gains tax in any of the above situations. Furthermore, if India were to re-introduce dividend withholding tax, the treaty provides that the amount of such tax will be either 5% or 15% depending on the circumstances. The (non-CGT) income received by the parent GBL1 company in Mauritius, whether in the form of dividends, interest or royalties, will be taxed in Mauritius at an effective rate of between 0% and 3%.5

The presumption under which India will not charge CGT in such cases is that it is the recipient treaty country which will charge the tax. Mauritius has no CGT and therefore the gains can flow through the GBL1 and out to the investor with no withholding of any sort. Typically, the shares in the GBL1 will be held by the Mauritius version of the BVI company, the GBL2. Income will pass up to that entity and can either remain where it is, thus in many cases deferring any "home country" tax or indeed be invested back into India or elsewhere.

The Devil is in the Detail.

The use of the GBL1 for these purposes has nonetheless to be strictly "treaty compliant". As with any other tax mitigation scheme the world over, it may always be open to scrutiny and challenge if the form is allowed to take precedence over the substance. In 2003, the Indian Supreme Court ended all doubts over the use of the Mauritius route for inward investment to India. Their judgement confirmed the legitimacy of a Government Circular stating that a Certificate of Tax Residency issued by the Mauritius Tax Authority was evidence that a company was resident in Mauritius. In order to obtain the Certificate (which will later be passed on to the Indian Tax Authorities), the GBL1 will have to demonstrate that management and control is firmly in Mauritius. This will be evidenced by:-

- Registered Office in Mauritius.

- At least 2 resident (non-corporate) Directors, one of whom will chair the meetings.

- Local Company Secretary.

- Local Auditor.

- Local bank account with all invested funds actually routed through a bank in Mauritius (no short cuts advised).

- All accounting records maintained in Mauritius

- Audited annual financial statements produced and filed with the Financial Services Commission and the Tax Authorities within six months of the year end.

- All Directors and Shareholders meetings to be in Mauritius (teleconference is acceptable as long as the meeting is chaired from the Island).

It is also crucial that in order to enjoy Capital Gains Tax exemption under the Treaty, the Mauritius entity must not have a permanent establishment ("PE") in India. If this were to be the case, the income attributable to the PE would be subject to tax in India. As there is a certain amount of subjectivity involved in the determination of a PE, careful consideration must be given as regards any management to be exercised in India.

Subsequent to 2003, there have been further circulars from the Government of India which acknowledged that there were other tests a company would have to fulfil to ensure that the Mauritius Company was entitled to benefit under the Treaty. These further tests are designed principally to ensure that the Mauritius Company is not a "brass plate" operation and that there is genuine substance over form.

Recently, the stand of the Indian Tax Authorities in matters of international taxation has aroused uproar in the finance industry in both Mauritius and India. A number of MNCs such as Vodafone, E*Trade and General Electric are involved.

It should be reminded that the Supreme Court of India in the landmark case of Azadi Bachao Andolan (2003) upheld the validity of the 'Mauritius route', which contributes to around 44 per cent of India's FDI. However, in the case of E*Trade, this did not preclude the Indian tax authorities from denying a Mauritian company from taking benefit of the India-Mauritius tax treaty. The Mauritian company was accordingly asked to withhold taxes on payments made to another Mauritian company for acquiring shares of an Indian company, thereby putting the tax treaty into question. The matter is being disputed in court.

Notable Competitors in the Ball Game.

While Mauritius remains the No. 1 source of such FDI routed into India, other IFCs are also catching up. European hub Cyprus is gaining ground as a favoured route for channelling FDI into the country. Investments from Cyprus amounted to US$ 2.6 bn in the April 00-May 09 period.

At this point I will also refer to the rise of Singapore as an International Financial Centre in recent years. It is true that this country has negotiated a quite similar DTA with India and is hoping to attract business that would otherwise have gone to Mauritius. As a matter of fact, Singapore replaced the US as the second-largest source of FDI into India with investments amounting to USD 8bn during the period April 2000-May 2009 The Singapore treaty does however contain two important differences which reduce its competitiveness. It lays down two eligibility conditions for capital gains tax exemption. These are listing on a recognised stock exchange and also a total annual expenditure on operations in Singapore in excess of S$200,000 (US$126,000) in the 24-month period from the date of the gains. One wonders if this is to encourage the corporate administrators there to increase their fees up to this level! Anyway, the Mauritius treaty with India does not include any such conditions.

Investing into India – the choice of approach

Many US and foreign investors have been investing into India, particularly into software development, business process outsourcing ("BPO"), drug discovery and other service companies. Before making such an investment, the need for a tax, exchange control and logistics efficient exit strategy has to be found.

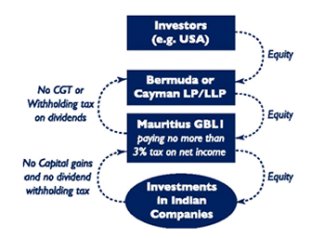

Typically, the US investor will start by having his "front end" investment structure as a US Corporation. This is often a Delaware Limited Partnership, large numbers of which are quoted on the NYSE and NASDAQ. The General Partner is the Promoter of the fund and the Limited Partners are the investors. US sourced funds can freely flow into the US based tax transparent entity. From there, the monies raised go to join non US source funds in a Cayman structure which in turn routes the investments through a subsidiary established in Mauritius.

Due to the flexibility and lightness of regulation found in Cayman, and the US taxation treatment afforded to US investors by using the Delaware LLP, we usually see this two tier approach being used. Moves are afoot in Mauritius at the moment to introduce limited partnership legislation to enable the jurisdiction to compete on a level playing field with Cayman, thus removing the need to interpose a Cayman entity in such arrangements.

As has been seen, the level of capital gains tax in India is at its most when the investments are into unlisted companies and particularly when short terms gains are expected. The "Mauritius Approach" is also the most applicable when the exit strategy is by private sale of the Indian company shares by its immediate holding company as Mauritius does not have capital gains tax.

From our experience we know that the bulk of Fund type business comes originally through US Investors but typically via Cayman, Bermuda, Ireland or Luxembourg fund structures.

A diagrammatical example

Conclusion

The recent decision of the Bombay High Court in E*Trade Mauritius Limited has certainly generated apprehension among the investors. Having said that, given that this does not constitute a ruling on the issue of chargeability of the capital gains to tax in India, unless amendments to the treaty have been agreed by both states or anti-abuse mechanisms introduced, the show will go on.

Therefore, the private equity funds, venture capitalists and hedge fund operators looking to the sub-continent for diversification into this exciting market place should be using Mauritius if they are not already doing so or continue using Mauritius.

The India/Mauritius Treaty is 19 pages long so clearly I have not covered every aspect of it. As I hope I have explained, the basics of the arrangements are not rocket science, even for a non-tax trained Trust Practitioner. However, the proof of the pudding (as they say) is in the owners of US$ 39 billion of assets invested into India through Mauritius since 2000, and they cannot all be wrong!

Footnotes

1. Long Term Gains are defined as those where the investment has been held for more than 12 months.

2. Short Term gains are those where the investment has been held for less than 12 months.

3. Provided the transaction takes place on the Stock Exchange and Securities Transaction Tax ("STT") has been paid.

4. For transactions outside the Stock Exchange.

5. The tax rate is 15% but a notional allowance is given of the higher of either (a) 80% of the income or (b) the actual tax suffered directly or indirectly by subsidiary companies further down "food chain".

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.