- in Australia

FOREWORD

Welcome to the fifteenth edition of Predictions for the Technology, Media and Telecommunications (TMT) sectors.

The last 15 years have been a golden era for innovation: multiple TMT products and services that we now take for granted were niche or non-existent back then.

In 2002, homes typically had dial-up Internet access, boxy television sets, wired speakers, standalone digital cameras, shopping catalogues and fixed line telephones. Photos were stored in albums and shelves bulged with CDs and DVDs; LPs had been banished to the attic or sold off.

'Candy bar' shaped mobile phones had monochrome screens and were predominantly used to make calls and exchange text messages. Instant messaging, e-mail, e-commerce, maps, search engines, photos, videos and other online services that are now routinely accessed via smartphones were predominantly PC-based at the start of 2002.

3G networks had only just launched commercially, offering speeds of a few hundred kilobits per second. As most homes still had dial-up Internet, it was faster for most people to visit a video rental store, return home, watch the film, and then return it rather than to wait for a file to download.

Over the last 15 years, connectivity has become steadily faster, enabling many new categories of service to become mainstream, including a number of current staple applications: search engines, social networks, video-on-demand, e- and m-commerce, app stores and online video games.

These new services have driven the growing appeal of digital devices; smartphones and tablets being the two standout devices to have emerged over the period. These new device types have tended to complement rather than usurp existing products.

While the past 15 years has witnessed startling change, it has also seen remarkable continuity. Broadcast television, radio, cinema, live entertainment, printed books and in-person meetings remain popular despite multiple digitally- enabled alternatives.

2016 promises to be yet another exciting year for the TMT sector. In this year's edition we look at a fascinating array of trends, each developing at its own momentum.

We look forward to the progress of cognitive technologies in enterprise software, to new approaches in accelerating mobile commerce check-out, and to the progression of graphene. We highlight the continuing strength of demand for the PC – especially among millennials.

We welcome the commercial launch of virtual reality, and note the continued growth of both premium sports (with a focus on football in Europe), as well as the emerging eSports sector. We expect mobile should become the biggest games platform in 2016, overtaking console and PC.

We observe that the key traditional media of television and cinema should continue to hold their own, even if not growing. We explore the current and near-term impact of ad-blockers on mobile advertising revenues.

We discuss key drivers of bandwidth demand including the emergence of Gigabit to the home, trends in photo sharing and a continued rise in data exclusive communicators, as well as the potential impact of the take-up of network-managed voice over data services.

Finally, we expect the used smartphone market to surpass $17 billion in trade-in value, making it a significant consumer device market in its own right.

We hope that you find this year's set of predictions an interesting read and that they bring a useful dynamic to your discussions.

TECHNOLOGY

Women in IT jobs: it is about education, but it is also about more than just education

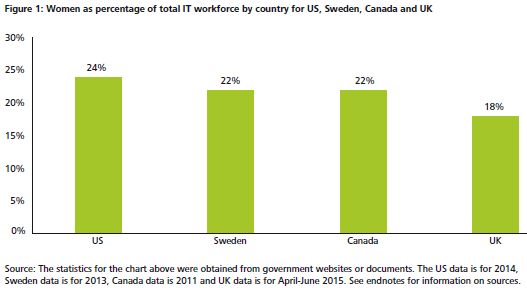

Deloitte Global predicts that by end-2016 fewer than 25 percent of information technology (IT) jobs1 in developed countries will be held by women, i.e. women working in IT roles (see Figure 1)2. That figure is about the same as 2015, and may even be down. Lack of gender diversity in IT is both a social and economic issue. Global costs may be in the tens of billions of dollars; according to one study, the gender gap in IT costs the UK alone about $4 billion annually3. Given that cost, gender parity (roughly 50 percent women in IT jobs) seems a reasonable goal over the long term. Why are the 2016 numbers less than half that goal, and why aren't they improving faster?

Gender imbalance in IT has been recognized as an issue since at least 20054. One might have expected some improvement since then, and perhaps even faster change since 2010, when there was a surge in articles about women in technology jobs5. That has not been the case.

For example, in the eight years between 2005 and 2013 the percentage of women in IT jobs in Sweden fell from 23 percent to 22 percent (although the percentage of women in senior IT roles did rise from 16 to 21 percent). In the US, which has five million IT jobs, the ratio of female IT workers also fell from 25 to 24 percent from 2010 to 20146, with the proportion of women in more senior roles declining three percentage points to 27 percent in 2014. In the UK, with 1.2 million IT posts, the percentage of women in IT jobs increased from 17 percent to 18 percent 2010-20157. In each market, the total number of IT jobs increased by over 20 percent in the last five years.

The education pipeline

Not every current IT worker has an educational background in computer science or other similar field. But in those fields of study, and especially in computer science, there are clear problems with gender diversity in the educational pipeline.

Only 18 percent of US university computer science (CS) graduates in 2013 were women8. And that was down from 1985, when 37 percent of graduates were women. UK figures are very similar: in the 2013/14 educational year, only 17.1 percent of computer science students were women9. That is much lower than overall female participation in higher education in the UK of 56 percent, and actually down very slightly from 17.4 percent in the 2012/13 educational year10. The percentage of women enrolled in mathematics, computer and information sciences at universities and colleges in Canada is higher, at 25 percent in 201411, but that is down two percent since 2009, when it was over 27 percent12. But at the best known computer science school in the country, the University of Waterloo, women made up only 13 percent of 2010 enrollment in computer science, down from 33 percent in the late 1980s although they now have a number of programs to get more women to enroll, and to retain them once they are in the program13. In Sweden as of 2010, women were 24 percent of computer science graduates14, down from 30 percent in 200015.

But the gender gap in the educational pipeline precedes university (tertiary) education. Only 18 percent of US students taking the Advanced Placement Exam for Computer Science in 2013 were women16. Once again, UK data is roughly similar: a 2012 survey showed that only 17 percent of girls had learned any computer coding in school, about half the level of the 33 percent of boys who had coded17. And some argue that girls are often steered away from science and math courses in primary school18. Other experts go earlier still, stressing the role parents need to take in encouraging girls younger than school age to be interested in science and technology19.

Challenges beyond the education pipeline

Recruiting. According to a 2014 study among UK firms, half of all companies hiring IT workers stated that only one-in-twenty job applicants were women20. Gender- neutral job descriptions are an important first step, but may not be sufficient, since the various algorithms driving online recruiting advertisements may mean women do not see the job placement ads21. In several studies, researchers found that the software showing ads for certain senior jobs targeted users tagged as men nearly six times as often as users labeled as women.

Hiring. Hiring more female recruiters may help, but will likely be an insufficient step. Various studies from multiple countries show that both men and women are twice as likely to hire a man for an IT job as an equally qualified woman22. That may not necessarily be conscious sexist behavior: there appears to be a number of unconscious biases at work that prompt even female recruiters to choose male candidates over equally qualified women. There are initiatives to help make people aware of their biases23 (the process is called 'unbiasing') but training and education may only partially offset them. Further, men and women in IT write their CVs in styles that vary by gender, and those stylistic differences may be making recruiters less likely to hire women24.

Retaining. Women in IT roles are 45 percent more likely than men to leave in their first year, according to a 2014 US study25. The study found that retention was a problem after the first year as well: one in five women with a STEM degree is out of the labor force, compared to only one in 10 men with a STEM education26. Issues that may be contributing to this lack of retention include pay and promotion (see below). A hostile or sexist 'bro- grammer' culture can also be an issue: in one study, 27 percent of women cited discomfort with their work environment, either overt or implicit discrimination, as a factor in why they left their IT job27. Further, workplace policies not suited to women, whether marathon coding sessions, expectations around not having children (62 percent of female IT workers don't have children, compared to 57 percent of men28) or lack of childcare may all play a role.

Paying and promoting. A US female web developer makes 79 cents to the dollar men make for the same job29; and while female computer and information systems managers have a narrower gap of 87 cents to the dollar, a pay difference is still prevalent30. The single largest category of IT workers in the US is 'software developers, applications and systems software' at over one in four of all IT workers – the pay gap for that group is 84 cents to the dollar31. In the US a quarter of women with IT roles feel stalled in their careers. In India the proportion is much higher, at 45 percent32. The number of female CIOs in the UK is 14 percent, and this has not changed in the last 10 years33; and a UK survey states that 37 percent of women in IT say that they have been passed over for promotion because of their gender34.

On the other hand, the issue of senior women in IT roles varies significantly by country. In the UK, where 18 percent of the IT workforce is female, the percentage of senior roles filled by women is half of that, at nine percent. In Sweden, 21 percent of IT chiefs are female, in line with the 22 percent of the IT workforce that are women. And in the US and Canada, the percentage of IT managers that are women is 2-3 percentage points higher than the percentage of all IT workers who are female. It is unclear why the gender gap for senior roles varies between countries, but it does suggest that cultural factors are playing a role.

The percentage of women in IT varies significantly by specialization and that variation also varies by country. As an example, in the US over 35 percent of web developers are female, while only 12 percent of computer network architects are women. Canada has a similar pattern, with web developers at the very high end of the diversity range and computer and network operators and web technicians at the lower end. On the other hand, the UK data shows that the percentage of web design and development professionals who are female is only slightly higher than the UK average for all IT jobs, likely one of the factors (along with the low number of women in senior IT positions) that contributes to the UK's poor performance on gender diversity in IT roles compared to all the other countries mentioned35.

It is important to note that diversity and inclusion are about much more than gender. As an example, ethnicity appears to be a significant factor in reaching senior levels in leading Silicon Valley tech companies: all of Hispanics, Asians and blacks are at a disadvantage to white men or white women at executive levels, according to a 2015 US study36. And of course, industries other than IT suffer from gender gaps for both participation and pay.

| Women in IT

companies Although the focus of this prediction has been on women in IT professions, there is a distinct but related topic of gender diversity within IT companies, specifically at the large American (usually Silicon Valley-based) companies. There are tech companies that currently publish their diversity numbers on an annual basis37 and they average about 32 percent female employees in 2014. These companies are a key part of the technology sector, likely represent the broader tech company employment picture, and are likely to be an important source of IT jobs for women going forward. But these companies have many workers in many different occupations, not all of which are IT jobs. One sample of six US tech companies showed that although their total workforce was 30-39 percent women, the number of women in 'tech jobs' was only 10-20 percent38. Increasing the gender diversity at these companies is likely an important goal, but only tangentially connected to the larger picture of women in IT jobs. Because of the considerable public spotlight on these companies as bellwethers for women in technology, it seems a reasonable prediction that the gender diversity numbers at high-profile publicly traded companies are likely to rise at a faster rate than for women in IT functions or jobs. Therefore it will be important to recognize that even if some Silicon Valley companies have 50 percent female employees that may not mean that the diversity of women in IT jobs across the US or developed countries in general has improved to the same extent. |

Although some of the numbers on gender diversity in IT may appear disappointing, there are also hopeful signs. At one leading US technology school, computer science is now the most popular degree for women39.

Furthermore, education may not be the gating factor that some think it is. While less than a fifth of US computer science graduates were women in 2013, as of 2014 the proportion of women in tech roles in US companies was 24 percent in 2014, and 27 percent of IT managerial roles were held by women40.

And speaking of leadership, there have never been more senior women in tech41, particularly high-profile female C-suite executives42: this is providing leadership, role models and mentors for women and girls considering a career in IT.

Another positive is that the IT job categories with the lowest female representation are shrinking over time, and the more balanced categories are growing43, suggesting that we may be nearing a tipping point in diversity. Further, tech companies are leading the broader IT industry: the US tech companies that released their gender diversity numbers in 2013 had an average of 30.3 percent female employees, and that number rose in 2014 by 0.15 percent44.

| Bottom

line Getting more girls and young women into streams that will lead to careers in IT will likely be difficult. Initiatives are under way to depict more positive female IT role models in the media45. But even if real progress is made immediately in improving gender parity in STEM at levels of the educational pipeline, it may take time (possibly decades, in the case of improvements to primary education) for those improvements to translate into IT job parity. Recruiting: firms could use software to screen for job descriptions that use words that are likely to turn away women: major technology companies are already doing this46. Another barrier can be tenure- related requirements: given the IT gender gap, requiring 20 years of IT experience shrinks the pool of qualified female candidates enormously. If lengthy tenure is a genuinely necessary requirement for the position, then it is appropriate, otherwise it would be an artificial barrier to hiring women. Hiring: having both men and women as part of the hiring process is likely to help. At one tech company, women who were interviewed only by men were more likely to turn down a job offer47. Now that at this company every female candidate meets with at least one woman from the company during the hiring process, more women are being hired. Women are sometimes less likely to promote themselves in interviews, and the same company now gets hiring managers to ask more detailed questions to paint a fuller picture. Retention: the attrition rate for mothers at one tech company was double that for employees as a whole: extending maternity leave from three months to five, and from partial pay to full pay, led to the attrition rate following childbirth falling by half48. A number of technology companies are looking at the role of mentoring: having more senior women support more junior IT workers is likely to lead to better retention49. Paying and promoting: IT prides itself on being a merit-based field. But gender differences need to be overcome: one company had its employees nominate themselves for promotions, and women were less likely to do so. In response, there are now workshops where women encourage other women to nominate themselves, and they are now being promoted proportionately50. The role of government: one possible solution may be for governments to take the lead, and attempt to increase the percentage of women in IT jobs in the public sector. Across all job types, the public sector tends to be more diverse than the private sector. According to the OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), women make up 45 percent of the total employment across all industries in 2013, but 58 percent of public sector employment, and the figure is 70 percent in Sweden51. Government leadership in IT employment of women does seem to work partially. Public sector IT jobs are 15 percent of all IT jobs in Sweden52. While 22 percent of Swedish IT jobs are held by women, for public sector IT workers it is a third, which suggests that government initiatives can at least help narrow the tech gender gap. On the other hand, that also means that private sector IT employment for women in Sweden is only a fifth. It seems likely that this dynamic also holds true in other developed countries: the public sector IT gender disparity is less pronounced than the national averages, and the private sector is therefore worse (by some amount) than the national average53. |

To read this Report in full, please click here.

Footnotes

1. This category refers to the professions identified by governments in the US, U.K., Canada, and Sweden. The US list of professions is: Computer programmers; Software developers, applications and systems software; Web developers; Computer support specialists; Database administrators; Network and computer systems administrators; Computer network architects; Computer occupations, all other; Computer hardware engineers; and Computer and information systems managers. Other countries have similar but different classification methods.

2. Deloitte Global estimate based on publicly-disclosed data from governments, and then population weighted.

3. See Lack of women in IT costing UK £2.6 billion a year, HR Magazine, 28 April, 2014: http://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/article-details/lack-of-women-in-it-costing-uk-2-6-billion-a-year; 2.6 billion GBP is roughly $4 billion.

4. Women are 'put off' hi-tech jobs, BBC, 8 September 2005: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4225470.stm

5. 2010: The Year of Whining About Women In Tech, ZDNet, 22 December 2010: http://www.zdnet.com/article/2010-the-year-of-whining-about-women-in-tech/

6. The job classifications in the US changed between 2010 and 2014 reports, but not enough to make comparisons meaningless. Data comes from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

7. The job classifications in the UK changed between 2010 and 2011, and have been steady to 2015. But the changes are not enough to make historical comparisons meaningless. Data comes from the Office for National Statistics

8. See Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women's Success in Engineering and Computing, The American Association of University Women (AAUW): http://www.aauw.org/research/solving-the-equation/

9. For more information, see Student Introduction 2013/14, Higher Education Statistics Agency: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/intros/stuintro1314

10. For more information, see Student Introduction 2012/13, Higher Education Statistics Agency: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/intros/stuintro1213

11. Postsecondary enrolments by institution type, sex and field of study (Both sexes), Statistics Canada, 30 November 2015: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/educ72a-eng.htm

12. Table 2 University enrolment by field of study and gender, Statistics Canada, 7 May 2011: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/100714/t100714a2-eng.htm

13. See Where the boys are and aren't, University of WATERLOO, as accessed on 14 December 2015: https://uwaterloo.ca/alumni/alumni-publications/waterloo-magazine/where-boys-are-and-arent

14. Closing the Gender Gap ACT NOW, OECD, as accessed on 14 December 2015: http://www.oecd.org/sweden/Closing%20the%20Gender%20Gap%20-%20Sweden%20FINAL.pdf

15. IT gender gap: Where are the female programmers?, TechRepublic, 6 April 2010: http://www.techrepublic.com/blog/software-engineer/it-gender-gap-where-are-the-female-programmers/

16. Detailed AP CS 2013 Results: Unfortunately, much the same, Computing Education Blog, 1 January 2014: https://computinged.wordpress.com/2014/01/01/detailed-ap-cs-2013-results-unfortunately-much-the-same/

17. ICT teaching upgrade expected ... in 2014, The Guardian, 20 August 2012: http://www.theguardian.com/education/2012/aug/20/ict-teaching-programming-no-guidance

18. STEM Fields And The Gender Gap: Where Are The Women?, Forbes, 20 June 2012: http://www.forbes.com/sites/work-in-progress/2012/06/20/stem-fields-and-the-gender-gap-where-are-the-women/

19. Parents Key in Attracting Girls to STEM, US News, 29 June 2015: http://www.usnews.com/news/stem-solutions/articles/2015/06/29/parents-key-in-attracting-girls-to-stem

20. One In Twenty IT Job Applicants Are Women, Say Majority Of Tech Employers, TechWeekEurope UK, 22 December 2014: http://www.techweekeurope.co.uk/workspace/it-job-women-157937

21. Google's algorithm shows prestigious job ads to men, but not to women. Here's why that should worry you, The Washington Post, 6 July 2015: http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2015/07/06/googles-algorithm-shows-prestigious-job-ads-to-men-but-not-to-women-heres-why-that-should-worry-you/?tid=sm_tw

22. How stereotypes impair women's careers in science: http://www.pnas.org/content/111/12/4403.abstract

23. Guide: Raise awareness about unconscious bias, re:Work: https://rework.withgoogle.com/guides/unbiasing-raise-awareness/steps/introduction/

24. The resume gap: Are different gender styles contributing to tech's dismal diversity?, Fortune, 26 March 2015: http://fortune.com/2015/03/26/the-resume-gap-women-tell-stories-men-stick-to-facts-and-get-the-advantage/

25. Keeping women in high-tech fields is big challenge, report finds, The Washington Post, 12 February 2014: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/keeping-women-in-high-tech-fields-is-big-challenge-report-finds/2014/02/12/8a53c6ac-93fe-11e3-b46a-5a3d0d2130da_story.html

26. Women Are Leaving Science And Engineering Jobs In Droves, ThinkProgress, 13 February 2014: http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2014/02/13/3287861/women-leaving-stem-jobs/ and Women's Progress In Science And Engineering Jobs Has Stalled For Two Decades, ThinkProgress, 10 September 2013: http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2013/09/10/2599491/women-stem/

27. It's the Culture, Bro: Why Women Leave Tech, Inc.com, 8 October 2014: http://www.inc.com/kimberly-weisul/its-the-culture-bro-why-women-leave-tech.html

28. Women's Progress In Science And Engineering Jobs Has Stalled For Two Decades, ThinkProgress, 10 September 2013: http://thinkprogress.org/economy/2013/09/10/2599491/women-stem/

29. Women web developers make 79 cents to the dollar men earn doing the same job, Narrow the Gap, as accessed on 11 December 2015: http://narrowthegapp.com/gap/web-developers

30. Women computer and information systems managers make 87 cents to the dollar men earn doing the same job, Narrow the Gap, as accessed on 11 December 2015: http://narrowthegapp.com/gap/computer-and-information-systems-managers

31. Women software developers, applications and systems software make 84 cents to the dollar men earn doing the same job, Narrow the Gap, as accessed on 11 December 2015: http://narrowthegapp.com/gap/software-developers-applications-and-systems-software

32. Keeping women in high-tech fields is big challenge, report finds, The Washington Post, 12 February 2014: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/keeping-women-in-high-tech-fields-is-big-challenge-report-finds/2014/02/12/8a53c6ac-93fe-11e3-b46a-5a3d0d2130da_story.html

33. Women in technology: no progress on inequality for 10 years, The Guardian, 14 May 2014: http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/may/14/women-technology-inequality-10-years-female

34. Gender imbalance in IT sector growing, HR Magazine, 30 March 2015: http://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/article-details/gender-imbalance-in-it-sector-growing

35. Data for Canada, US, UK and Sweden have been sourced from the offices for national statistics in the respective countries 36. Hidden in Plain Sight: Asian American Leaders in Silicon Valley, Ascend Foundation, May 2015: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.ascendleadership.org/resource/resmgr/Research/HiddenInPlainSight_OnePager_.pdf

37. For more information, see See how the big tech companies compare on employee diversity, Fortune, 30 July 2015: http://fortune.com/2015/07/30/tech-companies-diveristy/

38. We Aren't Imagining It: The Tech Industry Needs More Women, Lifehacker, 20 November 2015: http://lifehacker.com/we-arent-imagining-it-the-tech-industry-needs-more-wom-1743737246?utm_expid=66866090-67.e9PWeE2DSnKObFD7vNEoqg.0

39. Computer science now top major for women at Stanford University, Reuters, 9 October 2015: http://www.reuters.com/article/us-women-technology-stanford-idUSKCN0S32F020151009

40. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor, 12 February 2015: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

41. List of women executives at tech companies, Wikia, as accessed on 24 December 2015: http://geekfeminism.wikia.com/wiki/List_of_women_executives_at_tech_companies

42. The Most Powerful Women In Tech 2015, Forbes, 26 May 2015: http://www.forbes.com/sites/katevinton/2015/05/26/the-most-powerful-women-in-tech-2015/

43. Only 19 percent of system administrators were women in 2014, but there were 205,000 sysadmins in the US that year, down from 229,000 in 2010, an absolute decline of 24,000, and in a period when the IT sector grew by 757,000 jobs. Meanwhile 35 percent of web developers are women, a category that was added to the classification due to growth in jobs. http://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm and http://www.bls.gov/cps/aa2010/cpsaat11.pdf

44. See how the big tech companies compare on employee diversity, Fortune, 30 July 2015: http://fortune.com/2015/07/30/tech-companies-diveristy/

45. Google helps Hollywood boost girls-who-code image, USA Today, 18 March 2015: http://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2015/03/18/google-abc-disney-pair-up-to-promote-images-of-girls-and-computer-science/24903551/

46. Here Are The Words That May Keep Women From Applying For Jobs, The Huffington Post, 6 February 2015: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/02/textio-unitive-bias-software_n_7493624.html

47. In Google's Inner Circle, a Falling Number of Women, The New York Times, 22 August 2012: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/23/technology/in-googles-inner-circle-a-falling-number-of-women.html?pagewanted=2&_r=4&smid=tw-nytimesbusiness&partner=socialflow

48. Ibid.

49. How Mentoring May Be the Key to Solving Tech's Women Problem, The Huffington Post, updated on 4 October 2014: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/cassie-slane/how-mentoring-may-be-the-_b_4717821.html

50. In Google's Inner Circle, a Falling Number of Women, The New York Times, 22 August 2012: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/23/technology/in-googles-inner-circle-a-falling-number-of-women.html?pagewanted=2&_r=4&smid=tw-nytimesbusiness&partner=socialflow

51. For more information, see Government at a Glance 2015, 6 July 2015: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/download/4215081ec023.pdf?expires=1447602260&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=798872FE4BE4CA599C54771E8C4A1BA8

52. Public sector employers are (translated from Swedish): Government administration, State Enterprise, Municipal administration, County administration, Other public institutions, State-owned enterprises and organizations, and Municipally-owned businesses and organizations

53. Statistics are from publicly-disclosed data from Swedish central statistics database: http://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__AM__AM0208__AM0208B/YREG18/?rxid=9084f4d2-6ff6-45c0-b2c7-8eafc2328495

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.