From trading to owning?

Welcome

Welcome to the second in a series of reports representing a compilation of views from those in our firm engaged in commodity markets. In this report we focus on key themes in the oil and gas markets, using recent merger and acquisition activity as a reference point. Given the wide range of activity encompassed by this vast global business and the huge capital resources that it utilises, we have chosen to look at a single strand of the story – the systemic change affecting the commodity trading businesses operating in this space.

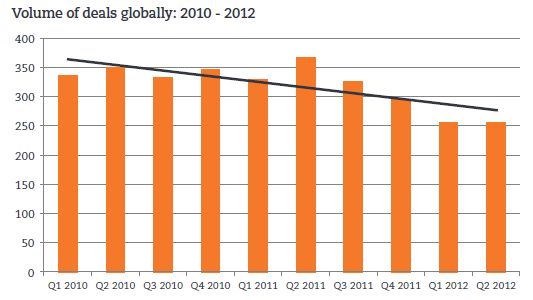

The world's reliance on oil and gas is still very heavy, and security of supply is a key issue for both governments and businesses operating in this sector. However, the trendlines in the chart on page 6 clearly show that the tightening of capital markets – restricting access to debt and equity funding – is acting as a brake on transactions. The pace of deals is slowing, particularly for those in the independent sector, a situation that large, well-capitalised majors and national oil companies (NOCs) may seek to take advantage of in the coming years. However, the deals being done illustrate some fascinating trends – both geographically and across sectors of the oil and gas market.

As international lawyers acting for a range of clients involved at all stages of the supply chain, we have seen increasing friction between the commercial imperative (usually securing reliable supplies and deliveries) and national interests (prompted largely by increasing resource scarcity). Over the last few years, both the frequency of government intervention in the markets and the types of direct and indirect tools deployed, have increased. A striking example of the risks of direct action for oil companies was the expropriation this May of Argentina's biggest oil company YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales). Repsol has since filed a claim at the World Bank's arbitration tribunal (ICSID) seeking USD 10.5 billion from Argentina for its expropriation of 51 percent of YPF.

A further political dimension has manifested itself through the deployment of international sanctions. Today, as events in the Middle East demonstrate, sanctions have become an important geopolitical tool that is being used more frequently and, sometimes, without universal international consensus. The upshot is that businesses have to keep track of a much more complex and fast-moving regulatory environment and must understand both the direct and indirect impact. The effect on the price of oil has been clear and immediate, but other sectors have also been affected.

Analysis of the deals themselves – especially the larger ones – shows that international oil companies (IOCs) are selling assets and splitting their refining operations from exploration and production activities, creating more "pure play" oil and gas businesses that focus on delivering growth and higher valuation multiples for their shareholders.

These assets are being sought by two main categories of buyers; the oil trading companies and emerging market NOCs. The former are looking to buy assets and enter into joint ventures across the supply chain from exploration and production through to storage and distribution, The latter, on the other hand, tend to come from resource hungry but rapidly expanding emerging market countries, seeking to secure a supply of essential fuel stocks, and consequently, are pursuing opportunities globally to acquire technological experience as well as reserves.

These far-reaching, inter-linked trends place the oil and gas sector at the centre of the global political and economic stage. Analysing how business models in these sectors are changing to meet rising demand amid scarcity and national interest is a vital element in how the global economy will evolve over the coming decades.

We hope that this report – and the perspectives it offers – will add to the debate. Further information on the report, and additional copies, can be obtained from any member of our commodities group (see page 23).

"We could envisage an investor coming in for a 10-20% stake in Mercuria if we could find the right partner ... but this is in the context of a long-term strategic partnership." Marco Dunand, CEO, Mercuria.

Executive summary

We are seeing the results of new strategic thinking by traders, both through the advisory work we undertake and from the nature of recent M&A activity. Historically, trading companies in the oil and gas sector have not invested heavily in expensive assets, leaving the large, vertically-integrated operators to own and control the entire supply chain from extraction to retailing. However, the picture is now shifting. Companies that previously focused on trading alone are taking steps to broaden their activities to acquire a range of assets across the value chain. In the process they are coming up against new and emerging forms of competition, as well as having to deal with increased political and regulatory risk.

To compile this report we have taken soundings from professionals across our commodities practice, and analysed deal data compiled by Thompson Reuters, including all completed M&A transactions in the oil and gas industries from January 1 2010 – June 30 2012. The data, which was sourced globally, includes both private and public companies and a variety of transaction types, and gives some clear indications of the shifts that are occurring. In recent years, many of the world's leading oil trading companies have transformed themselves from being 'asset light' organisations focused on pure trading, to complex structures with significant ownership interests stretching across the supply chain. This trend towards vertical integration has impacted not only on how trading companies do business but also on how they are structured.

From trading to owning

To execute their strategy, trading companies are reassessing their sources of funding, tapping the capital markets and changing ownership structures in order to generate the necessary revenue for acquisitions and investment in assets, all in an environment where traditional finance providers are deleveraging their balance sheets.

The assets sought range from new sources of supply through storage, refining and distribution. Many deals in the past year have involved traders purchasing strategically located ex refining assets for conversion into storage and distribution facilities. Such acquisitions secure a route to market and improved competitor intelligence. The real headline-grabbing deals, however, have been related to the trend towards securing new sources of supply, in particular the long-term bets being taken in the US and elsewhere on shale gas.

Extracting oil and gas economically from this geological formation has only been possible in recent years, but it now accounts for 30% of US gas production. A significant proportion of deals completed in the US have related to shale, as the drop in gas prices in recent years has made small independents (holding shale acreage in the US) more willing to sell.

Going against the flow

Traders are frequently buying from well-established integrated oil majors who are finding growth much harder to achieve in a tough environment, where new sources of supply are either technically challenging or difficult to access – sometimes because of political factors or increasing resource nationalism. In contrast to the trading community, the majors are turning to a strategy of demergers and divestments to create more "pure play" businesses in an effort to maximize shareholder value. Such a move has long been advocated by institutional investors as a way of improving the match between asset type and investor risk, which can be a value driver in its own right.

For example, Marathon Oil managed to turn a single USD 23 billion business into two worth a combined USD 36 billion by splitting its refinery and pipeline operations from its exploration and production business.

A competitive marketplace

In widening the sphere of their activities, trading companies have found themselves increasingly in competition with investment banks, as well as NOCs. It seems that competition from the bankers may decrease in light of new regulatory legislation in the US and UK, which is threatening to restrict their activity in this space and could prevent them from exploiting their physical trading expertise However, competition from the world's growing economic powers will only increase as they seek to fulfil their hunger for energy supplies by acquiring oil and gas reserves.

In the case of resource-hungry growing economic powers such as China and Russia, there is also increased competition for the trading community as new global players look to secure supply of essential fuel stocks. Well-funded and well-organised entities from both countries are actively looking at global opportunities, pursuing technological experience as well as reserves across the world from North and Latin America to Vietnam and South East Asia, adding further to the competitive challenges facing trading businesses with global ambitions.

Looking to the future

As their activities broaden, trading businesses find themselves facing a future which presents a plethora of new and complex challenges – ranging from political instability and resource nationalism to regulatory developments including the imposition of international sanctions (often as a response to such volatility). While there is little doubt that operating in this brave new world will cause trading businesses to alter and adapt their structures and activities, it will be interesting to see if they can do a better job with these new assets than their previous owners. In a world where shareholders' expectations regarding performance are higher than ever, and regulators are constantly striving for ever greater transparency and disclosure, trading companies will need to remain focused and flexible if they are to deliver on their ambitions.

Global trends

In terms of regional activity, North America led the field – accounting for 37 percent of activity – with Europe some way behind. The level of M&A activity in North America is linked to the shift in the supply/demand balance in the gas market and the pursuit of opportunities in shale gas. We are aware of the market's view that within the next few years the US will be self-sufficient in gas. This switch from being a net importer to a net exporter changes the entire nature of the trading market and will inevitably have a big impact on pricing.

Dr. Sit Kwong Lam, Chairman and CEO of Brightoil Petroleum Group, said "The acquisition not only further enhances our market presence in the oil and gas development and production business, but it also marks a significant step forward in our drive to become a leading integrated energy company."

From trading to owning

Commenting on this trend, Ian Taylor, CEO of Vitol said: "The strategy of all the IOC's1 has been to focus on material, upstream investments to provide future sources of growth. This has resulted in major divestment programmes, to include refineries, logistics assets and marketing businesses. While physical trading will always remain at the heart of Vitol, we have been able to take advantage of selective investments to add to our portfolio and continue to evaluate a number of future opportunities."

In recent years, many of the world's leading oil traders have transformed themselves from being 'asset light' entities focused on pure trading, to highly complex organisations with significant ownership interests stretching across the supply chain. This trend towards vertical integration has impacted not only on how trading companies do business but also on how they are structured.

Raising capital for acquisitions

One of the prevailing trends is an increased focus by trading companies on raising funds to enable them to secure supply, control distribution or widen their portfolios. This has resulted in a number of leading trading businesses either changing their ownership structure in order to raise additional capital or making public pronouncements of a willingness to contemplate such changes in future.

A prominent example is the listing of Glencore, but there are others. In December 2011, Mercuria, one of the world's top energy traders, in order to strengthen its balance sheet for future growth, raised almost USD 1.1 billion through a loan facility and agreed to sell interests in oil and gas properties in Bakken, North Dakota to Kodiak Oil & Gas Co. At the same time Mercuria acknowledged that it had received approaches from various potential investors, including sovereign wealth funds. In April 2012 the company announced it was in talks with potential investors to sell up to 20 percent of the company. "We could envisage an investor coming in for a 10 to 20 percent stake in Mercuria if we could find the right partner," said Marco Dunand, CEO. "But this is in the context of long-term partnership, as opposed to a fast investment turning into an initial public offering." Mercuria is seeking to expand and buy assets as it enters the metals and agriculture markets and to enlarge its operations in China and the UK.

In addition to structural changes , trading companies are also looking to the capital markets for new funding. In September 2012 Louis Dreyfus Commodities (LDC) raised USD 350 million through the issuance of a perpetual bond, this being the first time in the company's 160-year history that it has approached the public capital markets and the prospectus prepared in connection with the bond issue asserts that LDC wants to purchase or build "assets all along the value chain, both upstream and downstream". Interest in the bond markets also reflects difficult conditions in the equity markets – a few weeks earlier LDC postponed the planned IPO of its Brazilian sugar and ethanol business, which was expected to raise more than UDS 500 million. It also demonstrates that banks, and particularly the French banks which have traditionally financed the trading industry, have less appetite for lending as they strive to meet higher capital requirements, right size their own balance sheets and deal with increased counter-party risk

Asset acquisition

From the days in which they simply bought and sold, trading houses are now willing to spend significant proportions of their revenues to try and achieve greater control of every stage of the supply chain, from extraction to pump. In the oil and gas sector, however, taking control of the source is a much tougher challenge than for other commodities because of the capital and expertise required to exploit even proven fields. The trading community, while keen to secure access to supply, tends to tackle this through long term offtake arrangements, production sharing agreements and investment in upstream assets.

For example, in the last 12 months Vitol has concluded three significant deals. It entered into a long term purchase agreement with Sterling Oil Trading and Sterling Oil Exploration, for their new Nigerian Okwuibome crude oil production. It also formed a partnership with LPC Crude Oil Inc, giving it a presence in the gathering, marketing, and transport of oil and condensate in the Permian Basin in the US. Additionally, it signed a long-term Supply & Purchase Agreement for the annual supply of 400,000 tons of liquefied natural gas (LNG) with KOMIPO, a major Korean power company.

Commenting on this trend, Ian Taylor, CEO of Vitol said "The strategy of all the IOC's has been to focus on material, upstream investments to provide future sources of growth. This has resulted in major divestment programmes, to include refineries, logistics assets and marketing businesses. While physical trading will always remain at the heart of Vitol, we have been able to take advantage of selective investments to add to our portfolio and continue to evaluate a number of future opportunities."

In a similar vein,, in November 2011, Brightoil Petroleum Holdings acquired the Xinjiang Tarim Basin Dina 1 gas field, adjacent to assets it already owned. Dr. Sit Kwong Lam, Chairman and CEO of the Group, said: "The acquisition not only further enhances our market presence in the oil and gas development and production business, but it also marks a significant step forward in our drive to become a leading integrated energy company."

Seeking alternatives

One of the most active areas in terms of securing supply has been shale gas. Cleaner-burning natural gas has long been seen as the fuel of the future, but until now, concerns over price volatility and supply have prevented many domestic utilities and power companies from crossing over to natural gas from coal. Now, unconventional sources are providing a consistent, geographically accessible source of supply, which should continue to drive demand.

Many transactions in these areas are significant, and it is estimated that around USD 66 billion was spent on shalerelated transactions in the last year. The sector accounted for the largest reported deal of the year – BHP Billiton's acquisition of Petrohawk Energy for USD 15 billion, as well as Marathon Oil's acquisition of Hilcorp Resources' Eagle Ford shale properties for USD 3.5 billion.

Trading companies are also aware of the potential that is offered by shale gas and some are divesting non-core assets to focus on investments in shale oil and gas. In 2010, Noble Energy made two US shale acquisitions – Suncor and Twister Prospect – and in September 2011 entered a joint development agreement with CNX Gas Company for assets in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. In July 2012, Noble announced the sale of 900 conventional wells in Oklahoma and Texas to Unit Corp for USD 167 million. David L. Stover, Noble Energy's president and COO, said, "This sale is part of our previously announced non-core divestiture plan which will allow us to allocate capital and people to high-value and high-growth areas."

There are, however, significant environmental concerns associated with shale gas extraction. The extraction process, known as "fracking", involves pumping water, sand and chemicals into the rocks where the gas is trapped. Environmental campaigners are concerned that fracking has the potential to contaminate drinking water with methane or drilling chemicals. Other concerns include a potential link between fracking and seismic activity, the amount of wastewater the process generates, the clearing of forests for fracking sites and the emission of methane.

Storing it up

In the last year, a significant number of transactions have involved terminals, illustrating the crucial role played by storage in the supply chain and its potential to provide traders with options. Recent years have seen an increasing demand for storage capacity, especially in North America and Europe. This is due to the geographical distances between refining production and consumption, and a rise in demand for products with different specifications. This has led to a greater need for segregated storage and blending capabilities, and increased competition is expected to continue in Western Europe, where land is limited for new development in ports.

Capacity in refineries, however, is significant and this can be converted into storage. For example the collapse of Petroplus has led to the abandonment of refining at Coryton, which was a key supplier of transport fuels to south-east London. This facility will now serve in a more limited role as a storage terminal.

Vitol and Gunvor have bought plants from Petroplus in Cressier (Switzerland) and Antwerp (Belgium) with refining capacity of 68,000 b/d and 100,000 b/d, respectively. These acquisitions are strategically located – for example, Gunvor's is in the Amsterdam-Rotterdam-Antwerp oil trading hub – and offer not only a secure and rapid route to market, but also the possibility of delivering a significant competitive advantage over rivals by virtue of superior information.

Diversifying the portfolio

Businesses with cash to spend are not only looking towards vertical integration, but also to asset diversification – often by expanding into complementary sectors. Early evidence of this trend can be seen in Trafigura's 2010 purchase of a stake in Norilsk Nickel. In a similarly expansive move, in March 2012, Glencore announced a USD 6.1 billion bid for Canadian grain handler Viterra to add more agriculture operations to its core business, which had previously been far more focused on metals and energy.

Mercuria, on the other hand, has broadened its energy portfolio by expanding into coal. In late 2010 Mercuria bought a coal concession in Kalimantan, Indonesia and, in 2011, entered into a financing and partnership agreement with US coal producer Bowie Resources and bought a 5.7% stake in South Africa's Optimum Coal Holdings.

Energy companies are not the only businesses hedging their bets by looking at other industries. BHP – the world's biggest miner – is keen to diversify its commodity exposure from metals into areas such as uranium, potash and gas, demonstrating this ambition in early 2011 with its purchase of $5 billion of Arkansas shale-gas assets from Chesapeake Energy. This deal increased BHP's oil and gas resource base by some 45 percent and created a foundation for further growth.

Going to market

There is also interest in downstream activities such as marketing and retail, although again trading businesses are often looking for joint ventures to enter this space. One of the largest retail marketing transactions, in terms of disclosed deal size, is the sale by Royal Dutch Shell of its downstream businesses in 14 African companies for $1 billion. Under the terms of the deal, Vitol and Helios Investment Partners, an Africa-focused private equity group, will own 80 per cent of a new joint venture, Vivo Energy, with Shell controlling the remaining 20 per cent. Vivo will operate more than 1300 retail stations across Africa under the Shell brand and will have access to around 1.2 million cubic metres of storage. For Vitol the JV provides a route to enhance their wholesale supply into a rapidly expanding market and an opportunity to build a relationship with an experienced partner. As Ian Taylor, Vitol's CEO commented in a press release, "Africa is a continent we know well. These two new ventures allow us to invest in Africa and its fast-growing economies, and grow all the businesses under the umbrella of the worldclass Shell brand for the benefit of our customers."

Going against the flow?

As trading companies seek to acquire assets, this raises the question – who is doing the selling and why? In a sector where operators have tended to own and control the entire supply chain, the signs are – and the deal flow would seem to support this view – that not everyone is moving in the same direction. Although it is early days, and there are differences between mature and emerging operators, the focus of the established oil majors appears to be shifting towards demergers and divestments - a strategy from which the traders are benefiting in their search for assets.

Tough at the top

At the top end of the market capitalisation structure, the integrated majors face a tough environment as they try to grow their business. A major trend illustrated by the M&A data has been how companies have initiated transactions that will allow them to focus on their core business. A number of operators have been divesting businesses in order to maximise shareholder value – splitting their operations into separate entities to create more 'pure play' companies that focus on a single part of the process. In this way they gain higher valuation multiples since the traditional discount the stock market tends to apply to conglomerate businesses is removed.

Carve-out (meaning the separation of E&P from pipeline or refining) is one strategy being pursued to maximise market value. The rationale behind these splits is the volatility of oil refining versus the relative security of oil production. The former is profitable only when crude is refined as cheaply as possible into products that can be sold in the most lucrative markets. Most analysts believe that the risk/reward profile of the two types of businesses is very different and that it makes sense to separate them and attract investors with matching risk appetites.

Leading the slimline trend

Although other industry sectors have also been considering this strategy in what is a sluggish global economy, the oil and gas sector appears to be leading the trend. One of the first examples was Marathon Oil, which announced in January 2011 that it planned to separate its refinery and pipeline operations from its E&P business – a strategy advocated by its largest stockholder, Jana Partners LLC, for some time. Marathon created a subsidiary which owned just over half the company's pipelines and oil storage facilities in the Midwest and Gulf Coast region. The result? A single company valued at USD 23 billion became two companies worth a combined USD 36 billion.

Similarly, in July 2011, the third-largest US oil company ConocoPhillips, split its downstream refining and marketing operations into a new company, Phillips 66, leaving the remainder as the world's largest business operating solely as an oil and gas explorer and producer. Conoco had also been selling assets, including its 20 per cent stake in Lukoil of Russia, in what has been described as a "shrink to grow" strategy, rationalising the company to achieve future expansion. Jim Mulva, the then chief executive, said at the time that the rationale was to "unlock shareholder value in an intensely competitive industry".

This trend also extends to new and developing markets. Sinopec plans to hive off some non-core assets, a process that will include consolidating its oil services and engineering subsidiaries into a new unit that will then be taken public. No date is yet set for the public offering but analysts expect it could come late in 2013 or early 2014.

One company most analysts believe is a prime candidate to streamline its operations is BP plc – JPMorgan, for example, has been calling for a split of the group since 2006. Although many of its recent asset sales have been driven by the need to meet the costs of the Deepwater Horizon spill, the company has been focusing its disposals on its downstream activities. The latest is the USD 2.5 billion cash sale of the Carson refinery in California, which BP has agreed to sell to Tesoro Corporation. The 266,000 barrels-per-day refinery is being sold along with its associated logistics network of pipelines and storage terminals.

Giving something back

At the top end of the market there have also been transactions designed to prioritise financial discipline and the return of capital over ambitious growth plans – leaving the field clearer for growth hungry trading businesses.

It is the age-old story of the short versus the long term. In difficult economic conditions, with new reserves expensive to find and develop, capital providers are increasingly pressurising the oil and gas companies to deliver a short term fix to support falling share prices. In response, businesses are announcing buyback programmes and/or special dividends, or are implementing structured or progressive payout policies that return money to shareholders over the cycle.

BHP Billiton bowed to investor pressure in 2011, announcing plans to hand back USD 10 billion and invest USD 80 billion on development and expansion projects over the next five years, rather than a major acquisition. BHP chief executive Marius Kloppers said the company's acquisition sights remained focused on long-life, low-cost, expandable assets.

ConocoPhillips announced as much as USD 10 billion in stock buybacks in early 2011 – in addition to an existing USD 5 billion buyback programme. Conoco has sold more than USD 15 billion in fields and filling stations from Australia to Canada to monetise assets over the last few years. The latest share buyback returned some of that cash to shareholders. At the same time, it announced plans to invest USD 13.5 billion in 2011 to drill wells, build oil platforms and repair refineries, a 21 percent increase over its 2010 capital-spending plan.

A competitive Marketplace

While the traditional oil and gas companies may be ploughing a different strategic furrow in terms of M&A, trading companies still face considerable competition from other entities, such as investment banks and national oil companies, in their search for physical assets.

As commodity prices have risen over the last few years, the investment banking community recognised an asset class in which they could be more actively – and, profitably – involved. Instead of confining themselves to exchange traded and over-the-counter derivatives, a number of banks created physical trading desks for commodities such as oil and gas. According to Coalition, a company which analyses the performance of investment banks, commodity revenues increased by 55% in the first quarter of 2011 at a group of ten large banks – including Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, J.P Morgan Chase , Citigroup, Bank of America and Barclays.

The last year has seen Wall Street banks become even more deeply involved in the business of supplying oil as they compete with traders in selling crude to refineries. J.P. Morgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Goldman Sachs have all recently struck deals to supply US refiners. The effect of persistently high oil prices on cash-strapped independent refiners means they have increasingly turned to banks to finance their stocks.

However, several key pieces of upcoming regulation are likely to have a significant effect on the banks' ability to trade on their own account, and to hold hard assets including warehouses, storage tanks etc and commodity trading houses are likely to benefit as a result.

In the US the Volcker rule, enshrined in the Dodd-Frank Act, restricts the ability of banks to use their own capital by banning proprietary trading and restricting investment in hedge funds which have been active in the commodities space. Meanwhile, in the UK, the Vickers report has recommended ring fencing retail banking activities from investment banking. In parallel, the Basel III proposals will increase regulatory capital requirements for banks and are also expected to impact on liquidity by creating a more capital constrained environment.

Banks are already withdrawing from certain areas of business and there has been a notable exodus of talent in affected areas to commodity trading firms. For example, last May, Mercuria hired Goldman Sachs co-head of commodities investment, Shameek Konar, to help CIO Paul Chivers manage the Swiss-based trader's global portfolio of energy assets.

Trade finance desks have been particularly badly affected by Basel III as trade finance assets are regarded as a relatively high risk. This development has coincided with a growing need for structured trade finance that can be used as a tool to attract business in the fast growing, but more volatile, new and emerging markets.

While a prohibition on proprietary trading could remove an important source of trading revenue for investment banks, commodity trading companies, such as Glencore, Vitol and Trafigura, will not be affected by these rules and such changes could therefore, in the short term, provide them with an opportunity to gain more market share. As well as acquiring talent, trading companies have taken advantage of banks' downsizing to expand their footprint globally. That said, a significant decline in banks' interest in commodities trading could, in the long run, have an adverse impact on trading houses as well because banks are important providers of liquidity in the markets.

In addition, trading companies are likely to face a number of challenges of their own going forward. First, the shortage of funds from the banking sector is likely to remain a difficulty across all markets. Secondly, the expansion of trading houses is likely to result in greater market concentration, which may in turn increase the regulatory burden on commodities firms, with the result that regulatory approvals and clearance from competition authorities will be required for their mergers and acquisitions. Indeed, there is already concern amongst global policymakers that some trading houses might become "too big to fail". In a recent speech, Timothy Lane, deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, said that some of the large trading houses and the physical trading operations of some large investment banks are becoming "systemically important".

Holding hard

Whilst the battle over proprietary trading has been well trailed since the 2008 financial crisis, another battle has been taking place less visibly as investment banks seeks to retain or expand their physical commodity operations.

The Federal Reserve has long believed that the banks it regulates should not own commercial enterprises, so as to avoid distorting the real economy, or exposing them to untold environmental, operational or legal risks. The conversion of Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley to Bank Holding Companies (BHCs) at the peak of the financial crisis (to gain emergency access to discounted Federal funds) created a serious potential issue for their trading operations.

Although many bankers confidently predicted that they would be able to carry on as before because they were protected by a key passage in the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999, the drafting of this provision is extremely vague and the debate over its interpretation has already consumed two-thirds of the five-year grace period that the banks were automatically granted when they became BHCs. The deadline for compliance with BHC rules is November 2013.

JP Morgan is a good example. In July 2010, it closed a USD 1.7 billion deal to buy the global metal and energy trading units of RBS Sempra, expanding the bank's physical footprint to 25 locations, with more than 130 storage and warehousing facilities. However, when Royal Bank of Scotland bought into Sempra Commodities in 2008, the Federal Reserve said the unit would have to sell off the US assets of the Henry Bath warehousing company which was part of the deal. This leaves open the question of whether J.P. Morgan will be allowed to continue ownership of the same operations that RBS had been asked to divest.

If there is a requirement to dispose of these assets at the same time as proprietary trading desks are being closed and key traders are being lured away to the trading houses, this will be a significant blow to the banks.

New global players harbour global ambitions

Increasingly, trading companies are also having to compete for assets with resource-hungry emerging nations. As these emerging nations seek to secure supplies of essential fuel stocks, they are looking globally, pursuing technological experience as well as reserves. In shale gas for example, analysts estimate Asian reserves to be larger than those in the Americas. According to the US Energy Information Administrator, China holds 19% of global resources and, significantly, it held its first shale gas licensing round this year.

The Chinese are as active in oil & gas as in other natural resources. Groups which include PetroChina, Sinopec, Sinochem and Chinese National Overseas Oil Company (CNOOC), have a mandate to expand overseas and the means to do so. Sinopec is carrying out a restructuring project that is designed to bring more cash into the company and deleverage its balance sheet so it is in a position to adopt a more active global M&A strategy.

Sinopec is actively looking for opportunities and is starting to focus on developed markets and ambitious deals. In January 2012, Sinopec unveiled a USD 2.5 billion deal with Devon Energy, based in Oklahoma City, to invest in five shale oil and gas fields from Ohio to Alabama. It is also considering bidding for billions of dollars of assets owned by Chesapeake Energy, the US gas producer. Sinopec has also been active in Brazil. At the end of 2010, it acquired 40% of Repsol's Brazilian assets – planting its flag firmly in the South American market. While the Chinese producer already has a joint venture with Petrobras, this deal giving it a share of the offshore pre-salt reserves that are making Brazil the "new, new thing" in the oil world. It is likely that Repsol will seek to leverage this relationship for further co-operation in Argentina and Venezuela.

In July 2012, CNOOC bid USD 15.1 billion for Canada's Nexen. A previous multi-billion dollar bid for Unocal by CNOOC met with vehement political attacks from Washington which eventually resulted in the Chinese company dropping the bid. As a result most Chinese energy companies appeared to shy away from making large acquisitions of listed companies overseas, preferring to take minority stakes in companies without taking an operating role.

Confidence is rising

This latest bid for Nexen signals that confidence is rising, despite considerable regulatory hurdles. Approvals are required in Canada, where Nexen is one of the country's largest energy companies; in the US, as it has deepwater assets in the Gulf of Mexico; and also in the UK, where CNOOC will have to apply for an operator licence as the new owner of Nexen's assets in the North Sea. The acquisition has been carefully structured to appeal to regulators, although Canada's political opposition parties have raised concerns about CNOOC's environmental standards, industry insiders suggest that its close ties with China's government and its ability to honour its promise to keep current Nexen employees will help secure this deal. In the meantime the review period for the deal has been extended as the Prime Minister Stephen Harper seeks to address unease about the transaction.

Another prevalent trend in 2011 was international activity by Russian oil and gas companies. In September 2011, LUKOIL, one of the largest independent oil companies in Russia, made explicit its ambitions to expand overseas. Head of the company, Vagit Alekperov, said: "We are interested in buying upstream assets in the United States, Vietnam, and Southeast Asia. The company is interested in the acquisition of assets, including geological exploration."

LUKOIL has been active in 2012 – not just in upstream, but also in downstream and distribution. In April 2012 the company made a series of announcements stating that it was starting active development of the west Qurna-2 field in Iraq, commencing construction of subsea pipelines in the Caspian Sea, opening a new storage terminal in Barcelona in a joint venture with Meroil, and expanding its network of gas stations in Western Europe.

Other Russian oil companies have also been active. For example, TNK–BP has acquired a presence in Brazil and Vietnam and Rosneft has acquired an interest in Venezuela. It appears that this is as much to do with revenue-based taxation as it is to secure assets. The first stage of the new tax regime for the Russian oil industry came into effect from 1 October 2011 (the "60–66" regime), and it is likely therefore that this will continue to drive potential interest in mature assets.

BP is in advanced talks with Rosneft about a buyout of its 50 percent stake in TNK-BP. Should the cash and share deal go ahead, Rosneft will have complete control of the former JV going forward (becoming the world's biggest publicly traded oil company) and BP will become a shareholder in Russia's national oil company. It is widely reported however that Russia will press ahead to privatise Rosneft following the buyout.

Looking to the future

As trading businesses move from their historic position as providers of liquidity and logistical expertise to the market towards being owners and operators of strategic assets in which governments have a strong interest, they are likely to find themselves facing new – and possibly exacting – challenges.

Reference pricing coming under scrutiny

In the wake of the Libor scandal, oil reference prices have also come under scrutiny because of the similarities in the way the prices are calculated. Oil reference prices are calculated by two main price reporting agencies – Platts and Argus - on data collected from firms which trade oil on a daily basis, like banks, hedge funds and energy companies.

According to a recent report by the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO), the current system of oil price reporting is "susceptible to manipulation or distortion," because of the potential for selective price reporting and the submission of false information.

Dealing with disclosure

Historically there has been a dearth of information on payments by oil and gas companies to foreign governments. This is about to change in a way which could require greater disclosure across the energy sector, and eventually impact on oil trading. Although an industry backed Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) exists, and is designed to improve transparency in the natural resources industries by encouraging publication of payments by mining and oil companies to governments, the scheme has been voluntary and to date has not captured payments between national oil companies and traders.

The position, however, has now changed due to new US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations imposing mandatory reporting requirements on oil, gas and mining companies. These regulations require disclosure of payments made to governments in exchange for natural resources. This significant new disclosure requirement applies to all companies listed on a US exchange and is expected, in practice, to capture some 90% of all major internationally operating oil and gas companies.

Although the regulations do not apply to oil companies owned by governments of oil producing countries such as Saudi Arabia, all three major Chinese oil companies – PetroChina, CNOOC and China Petroleum and Chemical Company – will be caught by the new regulations and required to provide full disclosure.

The European Union is considering similar rules. Although the new mandatory disclosure requirements do not apply to privately-owned trading houses such as Vitol, Trafigura, Mercuria and Gunvor, there is pressure to extend the voluntary EITI scheme to oil trading which generates significant revenues for resource rich but otherwise poor countries. The trend for increased transparency and greater disclosure can also be seen in recent US sanctions legislation - the Iran Threat Reduction and Syria Human Rights Act of 2012 extends existing sanctions targeting Iran to new sectors of the Iranian energy industry and imposes a new SEC disclosure obligation on SEC registered public companies involved in a wide range of activities that relate to Iran.

Bribery and corruption remains a concern for entities operating in this sector, particularly in developing countries. Anti-corruption legislation is becoming increasingly extra-territorial and is being more aggressively enforced. As well as the "far reach" of the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the UK Bribery Act came into force in 2011 and is widely seen as one of the most stringent and widely applicable anti-corruption regimes in the world.

One consequence of these various new pieces of legislation and proposed legislation is increased due diligence on the part of the oil, gas and mining companies negotiating concession agreements with governments in order to ensure compliance with all applicable disclosure requirements and anti-corruption regimes.

A national interest

Owning assets means businesses become increasingly susceptible to the periodic outbreaks of resource nationalism that have affected Latin America and Africa in particular – as shown by the recent expropriation of Argentina's biggest oil company YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales) in May 2012, and other forms of political unrest.

While such action may have short-term populist appeal, the reality is that national energy companies need international investors to help develop big, deep or unconventional resources with foreign cash or sophisticated technology. One example of a trend away from nationalisation is in Mexico. Pemex (Petróleos Mexicanos), the state oil company is still constitutionally barred from bringing in private capital, but this looks likely to change with a change in government.

While the energy resources tied up in many of these more volatile countries are simply too great to ignore, political uncertainty in those countries may mean some investors are tempted to take a more "wait and see" attitude. Trading companies on the other hand, with their greater appetite for risk, may just count it as the cost of doing business, particularly when such risk can be mitigated by structuring investments to take advantage of bilateral investment treaties. Not only do such treaties generally provide for neutral international arbitration rather than recourse to local courts, they also give investors direct rights against host states, for example, in the case of unlawful expropriation or other discriminatory matters.

Political tensions also impact the oil sector in other ways, for example through the distortions introduced by sanctions. In the short-term, when effective, sanctions impact prices and price volatility. With the EU agreeing to stop oil imports from Iran by July 1 2012, the UN authorised and US-led sanctions against Iran have gained some extra bite, although China and India, which consume about one third of Iran's oil exports, have not agreed to cut back significantly. Longer-term sanctions will impact investment flows both by reducing Iran's access to the products and technology it needs for the oil sector and also by deterring inward investment by multinational oil companies. A Bloomberg news study concluded in July 2012 has suggested sanctions could cost the Iranian regime as much as USD 48 billion per year in oil revenues, an amount equal to about 10 percent of Iran's economy.

Flicking the switch

Gas has long been dominated by a handful of energy superpowers – countries such as Russia, Norway, the Netherlands, Algeria and, more recently Qatar – and the connections between producers and consumers created by pipelines and LNG tankers have created a well-established network between supply and demand. Sellers and buyers in this market have historically been well-established and have underwritten projects from 'cradle to grave'.

A significant 'game changer' in this industry – one which throws up opportunities for new entrants such as trading companies – is the growing interest in LNG exports from the US. With burgeoning US natural gas production and the large price differential between domestic and overseas markets, a number of companies plan to export surplus US gas – and at prices much lower than those set by other producers. For the global energy market this is a change of potentially huge proportions and one which may have significant geopolitical consequences if it means that the US will become self sufficient in energy.

For example, Houston-based Cheniere Energy completed a multi-billion dollar deal during the second half of 2011 to export natural gas, taking advantage of the very large price differential between US and Asian natural gas. Cheniere's export contracts are sold at a price indexed to Henry Hub, the main US gas benchmark, which currently trades at less than USD 2 per million British thermal units (mBtu). After liquefaction, transport and other costs, LNG could be imported into Asia for less than USD 9 per mBtu – compared with a long-term contractual price of USD 17 per mBtu in Japan.

Buyers included BG Group of the UK, which signed a 20-year contract – the first long-term LNG purchase agreement from a project on the US Gulf Coast. Korea Gas Corp, one of Asia's largest LNG buyers, Spain's Gas Natural Fenosa and GAIL, a state-owned Indian company, were also buyers. Cheniere has now sold 16m tonnes a year of LNG – or nearly 90 percent of its export capacity.

Cheniere may be ahead of the game but there are others looking to get into the gas export game. Eight projects with a total export capacity of 120m tonnes a year have been proposed, according to Wood Mackenzie, a consultancy. If all are approved and built, the US could become one of the world's biggest LNG producers. Qatar, the current world leader, has a production capacity of 77m tonnes a year.

Conclusion

There is evidence that the established oil majors are moving away from the fully vertically integrated model that had, in the past, enabled them to exercise control over the entire supply chain from the oil well to the petrol station forecourt; instead, they appear to be divesting assets and splitting their refining operations from exploration and production, thus creating more "pure play" oil and gas businesses focused on delivering growth and higher valuation multiples for their shareholders. The strategy is one of "shrink to grow", rationalising the business with a view to securing income streams and providing platforms for future expansion.

It also appears that, as the oil majors slim down, two main categories of buyers have stepped in – oil traders and emerging market based NOCs.

Traditionally, traders used to avoid heavy investment in fixed assets; it is clear, however, that their approach in this regard has changed and that, increasingly, control over key assets is seen as an important component in complex trading strategies. Although there have been a number of significant outright acquisitions by oil trading companies, there has also been extensive use of joint ventures. In fact, JVs involving trading companies have been entered into across the supply chain from exploration and production through to storage and distribution, suggesting that JVs are seen by trading companies as key to managing risk associated with entry into new markets and limiting exposure on fixed asset plays. Certainly, having a local partner can help to facilitate investment and ease the way through issues often at play in such markets. Another noteable trend is that some of the world's leading trading companies are changing their sources of funding and are, in some cases for the first time, tapping into the public capital markets. This trend has been given impetus by the reduced risk appetite of traditional trade finance banks, which are now more regulated and more capital constrained.

At the same time, NOCs of resource hungry high growth economies, are becoming increasingly prominent as they seek to secure supplies of essential fuel stocks. In doing so, they are pursuing opportunities globally in order to acquire both technological experience and know-how as well as reserves.

Although it is too early to draw any definitive conclusions about the process, it does appear that the market is in a state of flux and that this has created significant opportunities for new entrants and rising second tier players. Quite how this will play out in the long term, however is less clear. The very same financial and regulatory pressures on established oil majors and investment banks that have helped create investment opportunities for trading companies and emerging market NOC's may ultimately, be brought to bear on them as well. At the same time, the full impact of large scale LNG production in the US is extremely difficult to predict, as are the risks flowing from the possibility of political intervention in some of the less stable energy producing countries. That said, the mere fact that there are so many variables at play should give trading companies, with their greater appetite for risk and complexity, confidence that they will enjoy a key role in shaping the future of the global energy market.

If you would like further details on any of the themes we explore here, or to learn more about Clyde & Co's expertise in this sector, please get in touch.

"...the mere fact that there are so many variables at play should give trading companies, with their greater appetite for risk and complexity, confidence that they will enjoy a key role in shaping the future of the global energy market." Marko Kraljevic, Partner, Trade & Commodities, Clyde & Co

Clyde & Co Commodities team

Clyde & Co is a global law firm with a pioneering heritage and a resolute focus on international trade and commodities. With 1,400 lawyers operating from 30 offices across six continents and a network of more than 500 legal correspondents, the firm has the ability to provide advice and guidance on international trade across the globe.

Our commodities group is widely recognised as a market leader and ranked in the top tier of both the Chambers & Partners and Legal 500 legal directories and in the top 20 global firms in the Global Arbitration Review top 100.

We represent clients across the supply chain – from raw material to market, from market to processor and eventually to end user, acting for some of the most innovative and successful traders, shippers and financiers in the world. We offer pragmatic and commercial advice to steer them through the complex and diverse commercial challenges they face.

Our sector specific approach is unusual among law firms and ensures our lawyers understand the issues that are pertinent to this sector. The group provides contentious and non-contentious advice across the whole supply chain and across the full range of the commodity markets – hard and soft commodities, oil and energy, futures and derivatives (including newer specialisations such as carbon trading).

Our end to end experience and international coverage gives our advice a particular depth – wherever and whenever it is needed.

Footnotes

1. IOC's are international oil companies

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.