The development of pharmaceutical products is often expensive and unpredictable. Researchers investing the time and resources to develop a novel and non-obvious advancement over the art are rewarded with patent protection. It is therefore important to understand the framework applied by U.S. courts to determine whether an advancement is non-obvious, and therefore patentable.

This article examines three recent Federal Circuit cases—Endo Pharmaceuticals Solutions, Inc. v. Custopharm Inc., Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., and Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Actavis LLC, demonstrating how chemical and pharmaceutical formulation technology is highly complex and that the unpredictability present in drug development supports the non-obviousness of pharmaceutical patent claims.

Endo Pharmaceuticals Solutions, Inc. v. Custopharm Inc., a case brought under the Hatch-Waxman Act, involved Custopharm's attempt to market a generic version of Aveed®, a testosterone undecanoate (TU) intramuscular injection. The asserted patents, U.S. Patent Nos. 7,718,640 and 8,338,395, covering Aveed® claim three key elements: 750 mg TU, a vehicle containing 40% castor oil and 60% benzyl-benzoate co-solvent ('640 patent only), and an injection schedule comprising two initial injections at an interval of four weeks followed by injections at ten-week intervals ('395 patent only).

Custopharm argued that three clinical study references, namely the Behre, Nieschlag and von Eckardstein references, involving 1000 mg TU injections in castor oil, rendered the asserted patent claims obvious. None of the references disclosed the use of a co-solvent. The formulation vehicle used in the studies was 40% castor oil and 60% benzyl benzoate, but this was not known to the public until well after the priority date of the asserted patents. Custopharm also asserted the Saad reference, disclosing that the Behre, Nieschlag and von Eckardstein clinical study formulations used a 40% castor oil and 60% benzyl benzoate vehicle, but Saad was published four years after the asserted patents' priority date.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit agreed with the district court that Custopharm had not shown that the references inherently disclosed benzyl benzoate as a co-solvent or the particular ratio of solvent to co-solvent claimed, rejecting Custopharm's inherent obviousness argument. Inherency requires that "the limitation at issue necessarily must be present, or is the natural result of the combination of elements explicitly disclosed by the prior art."

Custopharm argued that the references inherently disclosed the vehicle formulation, because they recited the TU injection's pharmacokinetic performance, from which a skilled artisan could derive that the vehicle contained 40% castor oil and 60% benzyl benzoate. The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, explaining that the pharmacokinetic profiles in the clinical references did not necessarily point to the use of the claimed vehicle or bar the possibility of alternatives.

First, Custopharm had not shown that skilled artisans could extrapolate the vehicle formulation used in the clinical study references from the pharmacokinetic performance data. For example, Custopharm did not argue that the reported pharmacokinetic performance could only be attributed to the claimed vehicle formulation. Second, the prior art disclosed many potential co-solvents such that skilled artisans reviewing the clinical studies would not have necessarily recognized that the references' authors used benzyl benzoate as a co-solvent for their reported clinical studies.

The Federal Circuit credited Endo's expert's testimony that, based on the references' disclosures, skilled artisans would not have recognized that a co-solvent was necessary, and even if one was necessary, many were available. Moreover, Custopharm's expert conceded that even knowing the co-solvent's identity would not necessarily lead a skilled artisan to the ratio claimed in the asserted patents.

The Federal Circuit further rejected Custopharm's reliance on Proluton, a commercially available injectable composition of hydroxyprogesterone in a mixture of 40% castor oil and 60% benzyl benzoate administered weekly to pregnant women to prevent miscarriage. As the court explained, unlike Aveed®, Proluton is not a testosterone product for men. Moreover, Proluton is not an injectable steroid with prolonged activity. Consequently, the Federal Circuit was not persuaded that a skilled artisan would have turned to Proluton when formulating a long-acting, injectable testosterone therapy.

The Federal Circuit also rejected Custopharm's dose arguments. Custopharm argued that skilled artisans would be motivated to lower the TU dose from 1000 mg to 750 mg because, in view of the , patients in prior-art clinical studies were being overdosed. Under FDA guidelines, however, no patient received an overdose. Custopharm assumed that skilled artisans would have applied AACE guidelines instead of guidelines from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. However, the most commonly applied guidelines in clinical practice were the FDA's, and the clinical study references all employed, and the asserted patents cited, the FDA guidelines. Moreover, even if Custopharm's overdose argument was correct, skilled artisans could extend injection intervals instead of lowering the dose.

Custopharm also argued that once skilled artisans recognized that patients were overdosed with 1000 mg TU, the claimed injection schedule would be the result of routine treatment of individual patients and thus obvious. Nieschlag taught four doses at six-week intervals and that the intervals could be extended to up to 10 weeks or more due to drug accumulation. Von Eckardstein taught that the interval between doses could be increased up to 12 weeks. Together, Custopharm argued, these references suggested a first dosing phase with shorter injection intervals and a steady-state phase consisting of a longer, maintenance interval.

The Federal Circuit rejected this argument, first explaining that it was predicated on the overdose argument that the court already rejected. Second, the clinical study references did not teach initial loading doses followed by maintenance doses. Third, Endo presented evidence that injections like TU injections behave in unpredictable ways and that such dose and regimen changes would require more than routine experimentation. Specifically, the clinical study references did not disclose a linear relationship between dose amount and amount of TU in the patient's body. Accordingly, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court's ruling that the asserted patent claims were not obvious.

In Mylan Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Research Corporation Technologies, Inc., the Federal Circuit affirmed a ruling by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office in an inter partes review of U.S. Reissue Patent 38,551 finding the claims not unpatentable. The '551 patent discloses and claims enantiomeric compounds and pharmaceutical compositions useful in the treatment of epilepsy and other central nervous system disorders.

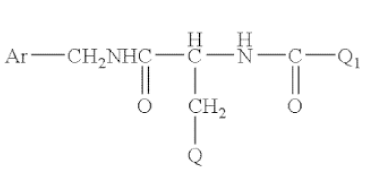

The compounds have the following formula:

where Ar is a phenyl group, which is unsubstituted or substituted with at least one halo group, Q is lower alkoxy, and Q1 is methyl. Claim 8, which the appellants challenged, recited the specific embodiment (R)-N-benzyl-2-acetamido-3-methoxypropionamide, known as lacosamide.

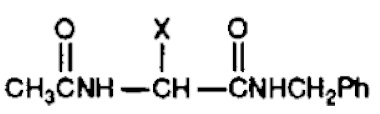

In the IPR, the petitioner advanced a lead compound analysis rendering certain claims of the '551 patent unpatentable over two prior art references, Kohn and Silverman. The petitioner offered compound 3l, disclosed in Kohn among other functionalized amino acids with anticonvulsant activity, as the lead compound:

with X being "functionalized nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur substituents." Kohn disclosed that the most efficacious compound tested in mice was compound 3l, where a "functionalized oxygen atom existed two atoms removed from the α-carbon atom," designated by "X." The petitioner further argued that Silverman, a drug design treatise, would have motivated skilled artisans to modify compound 3l to obtain the claimed lacosamide through bioisosterism, a "lead modification approach ... useful to attenuate toxicity or to modify ... activity."

Contrary to the petitioner's arguments, the USPTO found that converting the methoxyamino group in compound 3l to a methylene group would have been viewed as undesirable because the compounds in Kohn without a methoxyamino or nitrogen-containing moiety at the α-carbon had reduced activity. The USPTO also found that skilled artisans would have understood the methoxyamino moiety to confer significant activity to the compound and that substitution of nitrogen for carbon would have led to a significantly different conformation and biological activity.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit assumed that compound 31 was an appropriate lead compound, because the Court agreed with the USPTO that the petitioner had not demonstrated a motivation to modify that compound to arrive at the claimed lacosamide. The Federal Circuit found that even if skilled artisans would have been motivated to modify compound 3l, the evidence suggested that compounds without a methoxyamino or nitrogen-containing group at the α-carbon had reduced activity. The evidence also suggested that replacing the methoxyamino in compound 3l would have yielded a different conformation, and such a change might have affected interaction with receptors and altered biological activity. Kohn itself explained that "stringent steric and electronic requirements exist for maximal anticonvulsant activity," which, according to the court, would counsel skilled artisans against modifying compound 3l in a way that would change its confirmation significantly.

The Court also deferred to the USPTO's crediting of Research Corporation Technologies' expert over the petitioner's expert regarding the three-dimensional structures of compound 3l and racemic lacosamide. For example, the petitioner's expert agreed that a molecule's shape and potency may differ upon substitution of carbon for nitrogen. The Court also found that the USPTO could reject bioisosterism as a basis for a motivation to modify compound 3l. Specifically, Silverman disclosed that bioisosterism could be useful to attenuate toxicity in a lead compound, but the evidence did not indicate why bioisosterism would have been used to modify compound 3l in particular, which already had high potency and low toxicity, and why methylene was a natural isostere of methoxyamino.

In Endo Pharmaceuticals Inc. v. Actavis LLC, another case brought under the Hatch-Waxman Act, Actavis sought to invalidate claims of U.S. Patent No. 8,871,779, generally directed to compounds known as "morphinan alkaloids," such as "oxymorphone," used to provide pain relief in treated patients. The '779 patent discloses processes for preparing highly pure morphinan-6-one products with relatively low concentrations of impurities known as α,β-unsaturated ketone intermediate compounds (ABUKs) involving treating morphinan-6-one compound and ABUK mixtures with a sulfur-containing compound to reduce ABUK concentration to acceptable levels.

The prior art provided various processes for producing morphinan-6-one compounds involving catalytic hydrogenation of ABUK, but, according to the '779 patent, ABUKs could persist as impurities in the final products, and the hydrogenation processes may have tended to undesirably reduce a ketone group, a key functional part of morphinan-6-one compounds.

Actavis argued that three references, the Weiss, Chapman and Rapoport references, and an FDA requirement limiting ABUK content in oxymorphone to 0.001%, i.e., 10 ppm, rendered the asserted claims obvious. Weiss disclosed the use of catalytic hydrogenation to convert oxymorphone ABUK to oxymorphone. Weiss also explained oxymorphone diol as the product of hydration of the double bond of oxymorphone ABUK, oxymorphone ABUK's ready conversion to oxymorphone diol and oxymorphone diol's reversion to oxymorphone ABUK through hydrochloride application. Chapman disclosed processes employing catalytic hydrogenation to purify oxycodone ABUK into the salt form of oxycodone and processes converting oxycodone ABUK to oxycodone diol, an oxycodone ABUK precursor.

Oxycodone diol can revert to oxycodone ABUK through conversion to salt form, frustrating purification. Chapman, however, provides a reaction removing oxycodone diol from a sample before completion of purification, thereby preventing oxycodone diol's reversion to oxycodone ABUK. Rapoport disclosed a process using bisulfite addition to convert oxycodone ABUK to oxycodone, taking advantage of solubility differences of the products of reactions between bisulfites and oxycodone ABUK to separate oxycodone from oxycodone ABUK.

A majority of the Federal Circuit panel found that skilled artisans would not have had a reasonable expectation of success in combining Weiss and Chapman, because Weiss disclosed a material difficulty with using catalytic hydrogenation to purify oxymorphone to the FDA-mandated level, i.e., the production of relatively large amounts of oxymorphone diol, and Chapman did not teach a viable solution to this difficulty, given the differences between oxymorphone (and oxymorphone ABUK) and oxycodone (and oxycodone ABUK). Skilled artisans also would have lacked a reasonable expectation of success in using Rapoport's sulfur addition and separation process to remove oxymorphone impurities.

The majority also found that, based on the references' teachings, the FDA requirement also would not provide skilled artisans with a reasonable expectation of success in achieving the claimed purity levels for oxymorphone. The FDA requirement "introduced a market force incentivizing purification of oxymorphone to the level of the oxymorphone claimed" in the patent. But, the majority explained, the FDA requirement "recite[d] a goal without teaching how the goal is attained."

Even if the FDA requirement provided a general motivation to the opioid industry to achieve a particular purity level, the majority did not determine whether it provided the required motivation to combine, because the majority concluded that skilled artisans would not have had a reasonable expectation of success based on the references. The requirement did not convey anything leading one skilled in the art to view Rapoport's teachings differently, for example, or to believe that the described sulfur process might be more effective on oxymorphone ABUK.

Accordingly, the FDA requirement would not have overcome the references' disclosures indicating that skilled artisans would not reasonably believe their described methods could achieve the FDA-mandated oxymorphone purity level. The inventors' extensive experimentation, involving much failure, to ultimately produce the claimed oxymorphone, and their concerns that the FDA requirement "represented a dramatic, and potentially problematic, change in light of then-current knowledge and capabilities" further supported the majority's decision.

These three recent decisions by the Federal Circuit demonstrate that U.S. courts recognize the complexity of pharmaceutical development and formulation, and that the unpredictability present in drug development tends to support the non-obviousness of pharmaceutical patent claims.

Previously published in Bloomberg Law, August 29, 2019.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]