The America Invents Act1 introduced an inter partes review proceeding at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office for challenging the validity of a patent. Under the AIA, an IPR proceeding may not be instituted if the petition requesting the proceeding is filed more than one year after the date on which the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner is served with a complaint alleging infringement of the patent.2

The process of serving a patent infringement complaint is often routine and uneventful. While the federal rules require the plaintiff to serve a copy of the complaint and a court summons on the defendant, the defendant may choose to waive such a formal "service of process" in exchange for additional time to answer the complaint. Some defendants also may waive the formal service-of-process procedure as a professional courtesy, or agree to accept informal service through their outside counsel.

Given that an IPR petition must be filed within one year from service of the complaint, a defendant seeking to file such a petition may benefit from tolling the service date by requiring the plaintiff to complete a formal service-of-process procedure. The additional time required to formally serve the complaint may be particularly beneficial when the defendant resides outside the United States and must be served according to a foreign jurisdiction's rules, such as in compliance with the Hague Convention for Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters.

As discussed below, there may be cases where a non-U.S. defendant's advantages from waiving service of process are outweighed by the benefits of requiring the plaintiff to formally serve its complaint through the Hague Convention, thereby providing the defendant with more time to prepare and file an IPR petition and potentially seek a stay of the district court litigation.

Hague Convention Service of Process

Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, service of the complaint and summons on a foreign defendant may be conducted by any internationally agreed means of service reasonably calculated to give notice, such as authorized by the Hague Convention.3 Over 70 countries worldwide have ratified or adopted the Hague Convention as a mechanism for service of process, including most Western European countries, China, Japan and the Russian Federation.4

Despite the service requirement, many cases filed against foreign defendants never undergo a formal service-of-process procedure under the Hague Convention. Instead, many foreign defendants waive the service requirement because the federal rules provide foreign defendants with 90 days to file an answer to the complaint, instead of the standard 21 days, if they waive service.5

Service under the Hague Convention can be a lengthy and expensive process. Although each country sets its own requirements for service of process in that country, the Hague Convention mandates that each country at least provides a central authority to coordinate the service-of-process procedure.6,7 The Hague Convention, however, sets no time limits for completing the service procedure after the appropriate papers have been submitted to the central authority. Although the Hague Convention advises that most central authorities can accomplish service within two months, in practice, the process may take as many as six months to both serve the papers and return a proof of service to the serving party.8

The federal rules acknowledge the lengthy anticipated time for service of process in foreign countries, providing an exemption to the usual 120-day deadline for serving a complaint and summons on a foreign defendant.9 Some district courts have gone so far as to consider the litigation stayed until service is effected in a foreign country, even after the 120-day deadline has passed.10 In view of these significant potential delays for international service, the Hague Convention itself provides alternative methods of service that may be used if the central authority does not effect service within six months of the request.11

Accordingly, should a foreign defendant choose not to waive the formal service-of-process procedure under the Hague Convention, the delay due to the service process could extend the litigation at least two months, and as many as six or more months, while the parties wait for the proof of service of the complaint and summons.

One-Year Bar for Filing IPR Petition

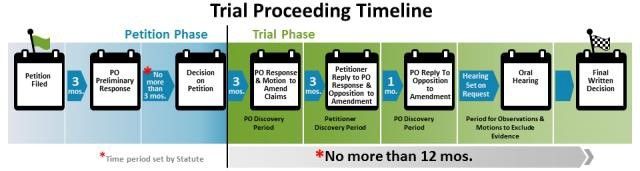

The America Invents Act established three types of post-grant proceedings for challenging patents before the Patent Trial and Appeal Board: (1) inter partes review; (2) post-grant review; and (3) the transitional program for covered business method patents. Each of these proceedings follows a similar timeline, as shown in the figure below published by the PTO.12 Each proceeding begins with the filing of a petition and ends, not more than 12 months following the PTAB's decision to institute the proceeding, with a final written decision. In the pre-institution "petition phase," the patent owner may file a preliminary response within three months of the issuance of a notice according a filing date to the petition, which the PTO typically issues within a few weeks from the petition filing. By statute, the PTO issues its institution decision within three months from the patent owner's preliminary response.13 Barring any extensions to the due date for the patent owner's preliminary response, the institution decision normally will issue no later than six months from the notice of the filing date accorded.

Although not shown in the timeline above, a party that has been sued for patent infringement cannot file an IPR petition based on the patents-in-suit more than one year after the petitioner, real party in interest, or privy of the petitioner has been served with the patent-infringement complaint.14 This one-year deadline for filing an IPR is sometimes called the "one year bar." The one-year bar starts when the defendant files a waiver or proof of service with the district court.15

Potential Benefits of Using the Hague Convention in Connection With an IPR

A common strategy for defendants, when sued in district courts for patent infringement, is to file one or more parallel IPR proceedings challenging the asserted patent(s). IPR proceedings have become an effective tool for invalidating patent claims, where it has been reported that the PTAB has canceled nearly 75 percent of all patent claims challenged in instituted IPR proceedings.16 In addition to this success rate, research has also shown that nearly 87 percent of patents challenged before the PTAB were also asserted in federal district courts.17

Other studies have shown an average time of six months between the filing of a district court case and a corresponding IPR petition.18 Assuming the defendant waives service of process soon after the complaint is filed, under the typical IPR timeline (above) the defendant may not receive the PTAB's decision to institute until about one year after the district court case was filed. This leaves little room for the defendant to file another IPR petition after the institution decision before the one-year bar expires.19

On the other hand, and as discussed above, service of process under the Hague Convention may take approximately six months to complete.20 Thus, a foreign defendant considering an IPR petition may benefit from insisting on formal service under the Hague Convention, thereby postponing the start of the one-year clock for filing IPRs.

One significant benefit of delaying service of the complaint using the Hague Convention is having extra time to prepare the IPR petition. To prepare a strong petition, defendants often must invest significant time and resources, for example, searching for prior art, reviewing the prior art, considering possible claim constructions in view of the asserted patent and its prosecution history, coordinating with expert witnesses, preparing any expert declarations, coordinating with litigation counsel, and preparing the IPR petition itself. This process can be even more time consuming when multiple patents, particularly unrelated patents, have been asserted in litigation and will be challenged in several different IPR petitions.

Another benefit of tolling the start of the one-year bar by insisting on service under the Hague Convention is that the defendant may have enough time to prepare a follow-on petition after the PTAB's institution decision. For example, the defendant may have time to prepare a second petition if the first petition was denied based on a procedural defect. The extra time to prepare and file follow-up petitions also may also be valuable for defendants challenging covered business method patents. A CBM petition is only granted for patents that claim a method or apparatus related to a financial product or service and not directed to a technological innovation.21 When facing the one-year bar restriction, some defendants may find the risk of noninstitution of a CBM petition too threatening to attempt if the patent is not clearly eligible for CBM review, since there normally is insufficient time for a follow-on IPR petition when the defendant waives service of process. By tolling the start of the one-year bar using the Hague Convention, however, the defendant may file the CBM petition knowing that, if its institution is denied on the grounds of CBM eligibility, the defendant can still have sufficient time to rework and refile the petition as an IPR petition.22

Using the Hague Convention also may benefit defendants seeking to stay the district court litigation pending a contemporaneous IPR review. Many courts consider the timeliness of the IPR petition as a contributing, if not controlling, factor in deciding whether to grant the stay.23 In general, the earlier the defendant seeks a stay based on an IPR proceeding, the more likely it will be granted. Indeed, some courts will not grant a stay until after the PTAB has instituted the IPR proceeding (rather than based on when the IPR petition was filed), and will deny a stay if the stage of the district court case has advanced too far before the IPR is instituted.24

Accordingly, insisting on service under the Hague Convention may increase the defendant's chance of being granted a stay. First, the delay caused by the formal service of process using the Hague Convention means the litigation may not procedurally advance until service has been completed; the early stage of the litigation will likely weigh in favor of a stay. Similarly, because some courts refuse to consider a stay until the PTAB has instituted the IPR proceeding, delaying service of the complaint may make it more likely the PTAB's institution decision would issue in the early stages of the litigation, as the institution decision is typically due within about six months after the IPR petition is filed. Further, with a possible delay of around six months for serving the complaint using the Hague Convention, the defendant also may be able to prepare and file the IPR petition before service is completed, making the "timeliness of filing" consideration also weigh heavily in favor of a stay.

Conclusion

For a non-U.S. defendant accused of patent infringement, insisting on service of process using the Hague Convention may provide several advantages, including extra time for preparing an IPR petition and any follow-on petitions, and a greater chance of being awarded a stay of the district-court case pending an IPR proceeding.

Footnotes

1 Leahy-Smith America Invents Act, HR 1249, 112th Congress (2011).

2 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

3 Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(f)(1).

4 See Hague Convention Signatory Member Table, HCCH, available at https://www.hcch.net/en/instruments/conventions/status-table/?cid=17 (last updated July 20, 2016).

5 Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(d)(3) ("A defendant who, before being served with process, timely returns a waiver need not serve an answer to the complaint until 60 days after the request was sent—or until 90 days after it was sent to the defendant outside any judicial district of the United States."); see also Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(a)(1)(A).

6 Convention of 15 November 1965 on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters, art. 2 (Feb. 10, 1969) ("Each contracting State shall designate a Central Authority which will undertake to receive requests for service coming from other contracting States and to proceed in conformity with the provisions of articles 3 to 6. Each State shall organize the Central Authority in conformity with its own law.").

7 Frederick S. Longer, Service of Process in China, ABA Section of Litigation 2012 Section Annual Conference, ABA Chinese Drywall Panel, at 2 (April 18-20, 2012) (with reference to service of process in China: "The papers to be served must first be presented to the Chinese Central Authority, which then is supposed to transmit the documents to local authorities for service upon the individual defendant. This takes time. Lots of it.").

8 Jennifer Scullion, Adam T. Berkowitz, & Charles Sanders McNew, International Litigation: Serving Process Outside the US, Practical Law (2011).

9 Fed. R. Civ. P. (4)(m) (exempting service in a foreign country from the usual 120 day requirement).

10 See Snyder v. Hall, 2008 WL 2838814, at *2 (C.D. Ill. 2008); Denton v. United States of America, 2006 WL 378395, at *1-2 (N.D. Ga. 2006); Vitaich v. City of Chicago, 1995 WL 493468, at *5 (N.D. Ill. 1995).

11 See In re South African Apartheid Litig., 643 F. Supp. 2d 423, 437 (S.D.N.Y. 2009); In re Bulk [Extruded] Graphite Prods. Antitrust Litig., No. 02-cv-6030, 2006 WL 1084093, at *3 (D.N.J. Apr. 24, 2006).

12 AIA Trial Proceeding Timeline, United States Patent and Trademark Office, available at https://www.uspto.gov/patents-application-process/patent-trial-and-appeal-board/trials (last visited Nov. 23, 2016).

13 35 U.S.C. § 314(b).

14 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

15 See, e.g., Macauto U.S.A. v. BOS GMBH & KG, IPR2012-00004, Paper 18 at 16 (P.T.A.B Jan. 24, 2013) (finding no service date under 35 U.S.C. § 315(b) because the patent owner did not demonstrate a service waiver or proof of service had been filed in district court); Motorola Mobility LLC v. Arnouse, IPR2013-00010, Paper 20 at 6 (P.T.A.B. Jan. 30, 2013) (finding "in the situation where the petitioner waives service of a summons, the one-year time period begins on the date on which such a waiver is filed."); see also Fed. R. Civ. P. 4(d)(4).

16 See Elliot C. Cook, Daniel F. Klodowski & David Seastrunk, Claim and Case Disposition, available at http://www.aiablog.com/claim-and-case-disposition/ (last visited Sept. 20, 2017).

17 Matthew Bultman, Most PTAB Petitions Involve Underlying Litigation: Report, Law360 (Feb. 12, 2016), available at http://www.law360.com/articles/758761/most-ptab-petitions-involve-underlying-litigation-report (setting forth the 87% figure); see also Saurabh Vishnubhakat, Arti K. Rai, & Jay P. Kesan, Strategic Decision Making in Dual PTAB and District Court Proceedings, Berkeley Tech. Law J. Vol. 31, at 20 (Feb. 10, 2016).

18 Saurabh Vishnubhakat, Arti K. Rai, & Jay P. Kesan, Strategic Decision Making in Dual PTAB and District Court Proceedings, Berkeley Tech. Law J., Vol. 31, Fig. 17 at 25 (Feb. 10, 2016).

19 35 U.S.C. § 315(b).

20 Jennifer Scullion, Adam T. Berkowitz, & Charles Sanders McNew, International Litigation: Serving Process Outside the US, Practical Law (2011). Additionally after six months, alternative service may be allowed. See In re South African Apartheid Litig., 643 F. Supp. 2d 423, 437 (S.D.N.Y. 2009); In re Bulk [Extruded] Graphite Prods. Antitrust Litig., No. 02-cv-6030, 2006 WL 1084093, at *3 (D.N.J. Apr. 24, 2006).

21 Leahy–Smith America Invents Act, HR 1249, 112th Congress, § 18(d)(1) (2011).

22 There are some limitations to this, as CBM review allows for invalidity challenges based on patent ineligibility, indefiniteness, lack of written description, or lack of enablement, whereas IPR review is limited to only prior-art challenges.

23 See Invensys Sys., Inc. v. Emerson Elec. Co., No. 6:12-CV-00799, 2014 WL 4477393, at *2 (E.D. Tex. July 25, 2014).

24 See Trover Group, Inc. v. Dedicated Micros USA, No. 2:13-CV-1047-WCB, 2015 WL 1069179, at *6 (E.D. Tex. Mar. 11, 2015) ("[T]he proper course is to follow the approach employed by the majority of the district court decisions (and all of the decisions in this district) and deny the motion for a stay pending a determination by the PTAB as to whether to grant the petition for inter partes review"); Flexuspine, Inc. v. Globus Med., Inc., No. 6:15-CV-201-JRG-KNM, Order Denying Mot. to Stay (E.D. Tex. Jan. 22, 2016) (denying motion to stay because "ruling on Globus Medical's request to stay this litigation before the PTAB has acted on the IPR petitions is premature").

Originally published in Law360

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.