INTRODUCTION

Although the U.S. is the world's largest economy, it is the only world economy that does not have a value-added tax ("V.A.T."). While most U.S. states impose state sales and use taxes to fund state and local governments, those taxes are imposed at much lower rates than the V.A.T. found in Europe. On the other hand, all world economies, including the U.S., have a corporate income tax. As a result, the U.S. is viewed to have attractive tax features because it competes with economies that raise revenue from both corporate income tax and V.A.T. – with V.A.T. often being the major source of revenue for national governments. Ongoing discussions about a potential repeal of the U.S. corporate income tax on exports and implementation of a U.S. border adjustment tax on imports have suggested that similarities exist with a V.A.T.

While both provide exemption for exports and taxation of imports, the border adjustment tax, as currently proposed, is a far cry from a V.A.T. Whether the two systems ultimately align will depend on the final version of the border adjustment tax, whenever enacted. For those who ponder on possible similarities, this article provides a baseline of comparison – it summarizes the V.A.T. mechanism drafted at the E.U. level.

V.A.T. OVERVIEW

Nature of a V.A.T.

Countries worldwide generally have the choice among four revenue-raising categories of taxation: income, wealth, wages, and consumption. A V.A.T. is a tax on consumption.

It is a tax on the value that every economic agent ("Taxable Person") in a given production and distribution chain adds to the produced good or the provided service. Upon the sale of that good or service, whether to the next Taxable Person in the production and distribution chain or to the final customer, a Taxable Person must collect V.A.T. from the purchaser at the applicable rate imposed on the value of the transaction. Because the person subject to the V.A.T. is the Taxable Person and because that Taxable Person collects the tax from the purchaser (as opposed to incurring it itself), a V.A.T. is referred to as an "indirect tax." As explained in further detail below, the Taxable Person is responsible for collecting V.A.T. and paying it to the relevant tax authorities. Such payment is referred to as a "remittance." The tax base is generally the value added by a given Taxable Person to the good or service – hence the name "value-added tax." In all V.A.T. systems, a mechanism must exist to prevent multiple levels of taxation as a product proceeds through a production and distribution chain.

Input V.A.T. v. Output V.A.T.

In a given production and distribution chain, a taxable person generally pays V.A.T. on goods and services purchased for its trade or business, and collects V.A.T. on goods or services sold in its trade or business. The V.A.T. that is collected is referred to as an "Output V.A.T." in the hands of the seller and an "Input V.A.T." in the hands of the buyer.

The following diagram best describes Input and Output V.A.T. in the hands of Producer 2:

A key characteristic of a V.A.T. is that the tax burden crystalizes at the level of consumption but is collected at each level of production. Filing and reporting obligations exist at every stage of the production and distribution chain, reflecting the view that the V.A.T. system should be self-policing, which it is to a certain degree.

Remittance of a V.A.T.

The computation of the V.A.T. amount owed to the tax authorities is based on a Taxable Person's Input and Output V.A.T. Thus far, countries have adopted three different methods to calculate the amount of V.A.T. to be remitted: the "Credit Method," the "Subtraction Method," and the "Addition Method."

Credit Method

Under the Credit Method, a Taxable Person deducts its Input V.A.T. from its Output V.A.T. and remits the difference to the tax authorities. This system generally implies compliance with specific invoicing requirements, such as the requirement to separately list V.A.T. on all sales invoices. Since V.A.T. in the E.U. can be imposed at different rates, this method allows a true-up to the proper rate when a product is sold to a Taxable Person in a different country.

Subtraction Method

Under the Subtraction Method, a Taxable Person must calculate the value it adds to the good or service it sells. It does so by subtracting the taxed input costs from the sales price of a good or service and then multiplying this difference by the applicable V.A.T. rate. The result must be remitted to the tax authorities. This method differs from the Credit Method in that only local costs are taxed at the Output V.A.T. rate, without affecting the actual rates of Input V.A.T. imposed on the Taxable Person. It accomplishes this by subtracting taxed input costs from sales price generating Output V.A.T.

Addition Method

Under the Addition Method, the taxpayer first calculates its added value by totalling all the untaxed costs of supplying the goods or services (such as wages) and then multiplies this added value by the applicable V.A.T. rate. This amount must be remitted to the tax authorities. This method simply ignores transactions and Input V.A.T. at lower levels in the production chain.

Most countries that are U.S. trade competitors have adopted the Credit Method. As a result, the remainder of this article will focus on this method, which can best be explained by the following diagram:

In this example, every Taxable Person in the production and distribution chain can deduct its Input V.A.T. from its Output V.A.T. and remit the difference to the tax authorities. Thus,

- the product producer remits the difference between V.A.T. 2 and V.A.T. 1,

- the derived product producer remits the difference between V.A.T. 3 and V.A.T. 2, and

- the retailer remits the difference between V.A.T. 4 and V.A.T. 3.

Only the ultimate consumer, who is not a taxable person, will bear the burden of the entire amount of V.A.T. incurred throughout the production and distribution chain.

THE EUROPEAN EXAMPLE

Overview

The E.U. was formed to implement a common European market. For this purpose, Member States transferred part of their sovereignty to the E.U. and its institutions. As a result, European institutions can draft legislation that applies to every Member State in certain areas only. Indirect taxes, such as V.A.T., are one such area.

The European V.A.T. system mostly originates from European directives. Once the European Commission issues a directive, every Member State must "transpose" the directive into its own legislation using the means it considers most appropriate to achieve the directive's goal. The V.A.T. directives give every Member State a certain degree of autonomy with regard to specific aspects of internal V.A.T. legislation. As a result, harmonization is not perfect among E.U. Member States – which explains, inter alia, the difference in V.A.T. rates among E.U. countries.

In broad terms, the following flow-chart best summarizes a European V.A.T. analysis:

International Aspects

Sale of Goods

For European V.A.T. purposes, three separate categories of cross-border transactions exist in relation to the sale of goods:

- Imports

- Exports

- Intra-community acquisitions

Imports are supplies of goods that are made from outside the European community, from so-called third countries in relation to the E.U. Generally, the acquirer or recipient of the goods must reverse charge ("self-declare") the V.A.T. due on this transaction. In common U.S. sales tax terms, this is a compensating use tax that applies when an item of personal property is acquired from outside the state and brought into the state. An example would be a valuable painting purchased in Paris and imported to the U.S. to hang on the wall of a New York City apartment owned by the purchaser. New York State imposes compensating use tax on the purchaser, as the purchase of the painting was not subject to New York State sales tax.

Exports are supplies of goods from a Member State to a consumer in a third country. With respect to U.S. sales tax, this is equivalent of purchasing a painting from a Beverly Hills gallery that ships the item to the purchaser so that it may be hung on the wall of a New York City apartment. California sales tax will not apply to the transaction.

Intra-community acquisitions are acquisitions of goods from a supplier established in another Member State. Intra-community acquisitions of goods and services are exempt in the Member State of the vendor and usually subject to V.A.T. in the Member State in which the supply ends. As a result, the acquirer must self-declare the V.A.T. due on this transaction. Again, to analogize to a U.S. sales tax fact pattern, this transaction is akin to the purchase of a painting from a gallery in Beverly Hills for delivery to a customer in New York City when the art dealer making the sales operates galleries in New York State and California. For sales tax purposes, the gallery must collect New York State sales tax but not California sales tax.

Sale of Services

The cross-border taxation of services is subject to slightly different rules. In broad terms, when the transaction relates to services and the recipient of the services has a V.A.T. number in another E.U. Member State, the recipient generally must self-declare the V.A.T. due on the services provided. On the other hand, when the services are provided to a person without a V.A.T. number in another E.U. Member State, the supply of services is generally taxable at the supplier's place of business.

To enable the various Member States to track supplies that are exempt from V.A.T. in one Member State but subject to V.A.T. in another, and to ensure that proper V.A.T. is collected, certain obligations are placed on Taxable Persons. These include

- the maintenance of a valid V.A.T. number in all E.U. Member States in which activities for V.A.T. purposes are conducted,

- the designation of a fiscal representative in certain cases to ensure that V.A.T. is collected properly and paid, and

- the filing of a European Declaration of Services or a European Declaration of Goods in which all provisions of intra-community supplies of goods or services are reported.

The Potential for "Carousel Fraud"

Carousel fraud in a V.A.T. context generally combines two elements of V.A.T. rules. The first is an intra-community acquisition of goods by a Taxable Person who is registered to collect to V.A.T. The second is the right to deduct Input V.A.T. related to the intra-community transaction.

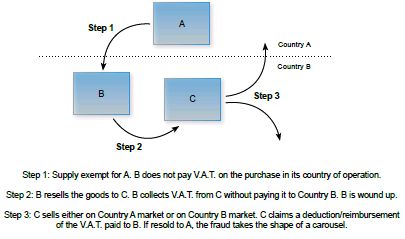

Generally, this type of fraud occurs in transactions subject to V.A.T. between at least three parties, as in the following example:

- A Taxable Person, A, in Member State A makes a taxable, but exempt, supply to a Taxable Person, B, in Member State B.

- In principle, B must self-declare Input V.A.T. to the tax authorities of Member State B. Nonetheless, B fails to declare and pay input V.A.T. on the intra-community acquisition.

- B resells the good to a related Taxable Person, C, without declaring the sale while charging and collecting V.A.T. on this supply. The collected Output V.A.T. is not declared by B.

- Shortly after the transfer, B is wound up, therefore embezzling V.A.T. proceeds from Member State B (and occasionally harming competition).

- C sells the final goods either in Member State B or in Member State A, collecting V.A.T. and claiming a deduction for the V.A.T. paid to B.

This type of fraud can best be illustrated as follows:

In reaction to this type of fraud, certain E.U. Member States have adopted legislation that makes every participant that knew or could have known about the fraud in this chain of fraudulent transactions responsible for the payment of the embezzled V.A.T.

CONCLUSION

While V.A.T. certainly raises valuable tax revenues, it also is a tax borne by the final consumer. As such, it has been referred to as an unfair tax on consumers with lower incomes, since lower income taxpayers will incur the same tax burden as higher income taxpayers, thus making the tax proportionately more burdensome for the former. In the U.S., some states have addressed this issue by allowing a refundable credit against state income tax for a fixed amount of purchases based on income levels. Only people with limited incomes are allowed the credit.

Having mastered this basic course in V.A.T. rules imposed by E.U. Member States, the reader is urged to compare these rules with the border adjustment tax when, as, and if finally adopted. The border adjustment tax proposed to date, dramatically differs from a V.A.T. because there is only one point of collection – at the point of entry to the U.S. As with a V.A.T., retailers and others in the distribution chain may attempt to pass the cost to the next person in the chain and on to the ultimate consumer. However, in comparison to a V.A.T., the next person in the chain may refuse to absorb the price increase.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.