On March 24th, the Supreme Court heard oral argument on the consolidated appeals of two decisions from the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, Bank of America v. Caulkett1 and Bank of America v. Toledo-Cardona.2 The appeals address an issue left unresolved by the Supreme Court's decision in Dewsnup v. Timm:3 that is, does section 506 of the Bankruptcy Code void, i.e., "strip off" a valid junior mortgage lien in a chapter 7 case if the mortgage loan is completely underwater. These cases involve the treatment in chapter 7 bankruptcy cases of "undersecured" or "underwater" second-lien home mortgages. Debtors who have granted such mortgages have no equity in their houses because the houses are worth less than the amount outstanding on the mortgage loans. Generally, there are two types of junior mortgage liens: closed-end lump-sum mortgage loans, and openend home equity lines of credit ("HELOCs"). Both of these cases involve closed-end, lump-sum mortgage loans, but the result would be the same for HELOCs.

In a chapter 7 case, an individual debtor is able to obtain a discharge of his or her debts following the liquidation of the debtor's non-exempt assets by a bankruptcy trustee, who then distributes the proceeds to creditors. In Dewsnup, the Supreme Court held that section 506 does not permit an individual chapter 7 debtor to reduce (or "strip down") a first-lien mortgage loan to the value of the real property where the amount owed is greater than the property value. Relying on Dewsnup, every circuit court to consider the issue except the Eleventh Circuit has determined that section 506 also does not permit individual debtors to void a completely underwater junior secured creditor's right to foreclose on the property securing the creditor's claim.4 Although the housing market has been rebounding in many jurisdictions, there are numerous properties subject to multiple mortgage liens that are worth less than the amount of the first-priority mortgage. The Supreme Court's resolution of the Caulkett and Toledo-Cardona cases will either ratify the trend of other circuits, which would benefit junior lenders, or overturn it, which would favor homeowners and first-lien mortgagees. A ruling prohibiting lien stripping also could severely impair the ability of business and individual debtors to use the statutory power to restructure and avoid liens in chapters 11, 12 and 13. Regardless of the outcome, the decision will have widespread ramifications through the secondary housing market.

The Supreme Court's Dewsnup Decision

Section 506(a) of the Bankruptcy Code states that an allowed claim is a secured claim "to the extent of the value of such creditor's interest in the estate's interest in such property." Section 506(d) provides that a lien is void "to the extent that [it] secures a claim... that is not an allowed secured claim."4

In Dewsnup, two individual chapter 7 debtors argued that section 506(d) voids the portion of a first-lien mortgage loan that exceeds the value of their home. The debtors had defaulted on an $119,000 loan secured by their personal residence valued at $39,000. (776). The debtors filed an adversary proceeding seeking to void the unsecured portion of the lien. In a 6-2 decision,5 the Supreme Court held that section 506 does not permit individual debtors to reduce (or strip down) the unsecured portion of a partially secured claim on their residence. Such an outcome, the Court noted, is consistent with pre-Bankruptcy Code practice, in which "liens pass through bankruptcy unaffected." (418). In the absence of prior practice, legislative history or other Bankruptcy Code provisions evidencing Congress' intention to void unsecured claims, it would be "contrary to basic bankruptcy principles" to grant debtors this "broad new remedy." (420).6 However, the Court acknowledged that section 506 "embrace[s] some ambiguities" and stated that it was "focus[ed] on the [present] case." The Court expressly limited its holding to the facts at hand, stating that it would "allow other facts to await their legal resolution on another day." (416-417).

Caulkett and Toledo-Cardona

Both Eleventh Circuit cases now on appeal originated in the Bankruptcy Court for the Middle District of Florida.

The Florida individual debtors in each of the cases sought to void closed-end, non-revolving term loans secured by second-lien mortgages on their homes. The value of the homes was significantly less than the amount outstanding on the senior mortgages. In each case, the Eleventh Circuit noted that it was bound to follow its precedent in McNeal v. GMAC Mortgage LLC,7 in which the court had ruled that 506(d) permits an individual chapter 7 debtor to void the claim of a wholly unsecured junior mortgagee. In McNeal, the Eleventh Circuit stated that Dewsnup did not dictate its holding, as Dewsnup did not address whether a debtor may avoid a wholly unsecured junior lien. (1265).

The debtors' principal argument is grounded in the plain language of section 506. Section 506(d) provides that "[t]o the extent that a lien secures a claim against the debtor that is not an allowed secured claim, such lien is void." Debtors state that "[a]ccording to ordinary rules of grammar," in order to be an "allowed secured claim," 506(d) requires that a claim be both allowed and secured. (12). Section 506(a) provides the definition of "secured," i.e., that a claim is "secured... to the extent of the value of [the] creditor's interest in... [the] property." If the value of a creditor's interest in the property is zero, the claim "is not an allowed secured claim" and is therefore void under 506(d). 11 U.S.C. § 506(d).

Dewsnup, debtors argue, "is not to the contrary." The case held merely that "a partially unsecured claim remains 'an allowed secured claim' [for purposes of 506(a)], and so prevents Section 506(d) from voiding the associated lien." (13) (quoting 11 U.S.C. § 506(d)). The debtors point out that Dewsnup's holding was "explicitly narrow" and did not address wholly unsecured junior liens. (8).

By contrast, Bank of America ("BofA") argues that section 506(d) voids underwater liens "only where the underlying debt is invalid under applicable law." (24). This position relies on distinguishing between the two components of a mortgage: a right in rem (against property) and a right in personam (against a person). One component of a mortgage is the note. The note gives the lender the right to proceed against the debtor for repayment of the loan. The other component of a mortgage is the lien. The lien gives the lender the right to proceed against the property—i.e., foreclose—in the event that the debtor defaults. (5) (citing Johnson v. Home State Bank, 501 U.S. 78 (1991)). The Bankruptcy Code refers to the lender's right to proceed against the debtor personally as a 'claim' and refers to the lender's right to proceed against the property as a 'lien.' (5) (citing 11 U.S.C. § 101(5), (37)). BofA argues that in defining an "allowed secured claim," section 506(a) refers to the lender's right to proceed against the debtor personally and the lien-voiding section 506(d) refers to the lender's right to proceed against the property. (26-27). According to BofA, "[f]or purposes of 506(d), 'an allowed secured claim' is an allowed claim secured by a lien with recourse to the underlying collateral, regardless of the collateral's value." (26). The value of the collateral serves only to dictate the treatment of the claim under 506(a). As a result, "[t]he collateral's value has no effect on the treatment of the creditor's lien under § 506(d)." (27) (emphasis in original).

BofA interprets Dewsnup as requiring this result. BofA noted that a "chapter 7 proceeding discharges only the debtor's personal liability on his or her debts; it does not affect a secured creditor's nonbankruptcy right to enforce its lien." (8) (citing Johnson, 501 U.S. at 84). Consistent with this concept, in Dewsnup, the Supreme Court noted the pre-Code practice that liens remain with encumbered property until foreclosure or debt repayment. (417). It follows that Congress did not intend 506(d) to effect such a "radical change in pre-Code practice" and thus must not have intended to void liens associated with unsecured claims, regardless of whether the claims are partially or wholly unsecured. (13).

BofA's interpretation, the debtors argue, is inconsistent with other provisions of the Bankruptcy Code. Reading 506(a)'s definition of secured status as inapplicable to 506(d) is at odds with other Bankruptcy Code provisions, which explicitly exclude certain provisions from the operation of section 506(a).8 Exclusions such as these demonstrate that the absence of an express carve out in 506(d) must mean that Congress intends 506(a)'s definition of secured status to apply. (19-20).

The debtors also argue that BofA's reading of section 506 "creates surplussage." (17). Section 506(d) states that "[t]o the extent that a lien secures a claim... that is not an allowed secured claim, such lien is void." According to BofA's reading of the statute, section 506(d) "strips only liens securing disallowed claims." (19) (emphasis in original). Under such a reading, debtors assert, "every 'lien that secures a claim' will be an 'allowed secured claim...' [t]herefore, the word 'secured' does no work at all." (17) (quoting 11 U.S.C. § 506(d)) (emphasis in original).

Lastly, the debtors argue that the policy considerations that motivated the Supreme Court's holding in Dewsnup—which BofA also adopts—do not apply to completely underwater junior mortgages. In Dewsnup, the Supreme Court was concerned that stripping off a partially in-the-money first lien would allow debtors a windfall, as the debtor would reap the benefit of any property appreciation between valuation and property sale.9 (417). By contrast, debtors argue, after stripping off a completely under water junior lien, any appreciation in property value will likely benefit the first priority mortgagee. In addition, it is unlikely that any increase in value would be great enough to result in a recovery to a completely unsecured junior lien. Voiding such a lien in bankruptcy is also consistent with the expectations of out of the money junior mortgagees, whose liens are extinguished in a foreclosure sale. In addition, senior mortgagees, the debtors stipulate, often require junior lienholders to confirm that their claim is subordinate to that of the senior mortgagee in order to approve loan modifications. Voiding valueless second mortgage liens permits first mortgagees and debtors to negotiate loan modifications without obtaining this approval. (38-39). This is especially true in the mortgage loan securitization market, in which loans are sliced into several tranches and sold piecemeal to multiple investors. In such circumstances, locating investors to obtain permission to declare their claims subordinate may be prohibitively difficult. Moreover, second mortgagees have already bargained for their subordinated position, for which they are already compensated by higher interest rates. (41).

BofA also advances additional arguments, namely, that the legislative history and "overall structure of the Bankruptcy Code... compels [their] interpretation of § 506(d)" and that Congress has repeatedly ratified their interpretation of Dewsnup. First, the Committee Report accompanying section 506(d) explicitly states that "[s]ubsection (d) permits liens to pass through the bankruptcy case unaffected." H.R. Rep. No. 95-595, at 357 (1978). Additionally, the Bankruptcy Code contains several provisions—such as section 1325(a)(5)(B)10—that permit debtors to strip down liens. These "carefully articulated provisions cannot be reconciled with a reading of § 506(d) that would strip all liens down to the value of the collateral." (35) (emphasis in original). Lastly, since Dewsnup, several bills that would expand debtors' ability to strip liens have been introduced. Congress has not enacted any of them. (20).

Conclusion

In the March 24th oral arguments, the Justices appeared to be particularly focused on whether Dewsnup should be overturned, even though neither party had expressly asked the Court to overturn it. Justice Scalia stated, "I dissented in Dewsnup, and I continue to believe that dissent was correct. Why should I not limit Dewsnup to the facts that it involved, which is a partially underwater mortgage." (Transcript of Hearing at 11).

Justice Kagan appeared to agree with Justice Scalia that "the court should bite the bullet and overturn Dewsnup." (Transcript at 45). A decision to overturn or uphold Dewsnup could impact the commercial mortgaged-backed securities market, if applied to underwater subordinate liens. In addition to the petitioner and respondent, numerous trade organizations have filed amicus briefs detailing these consequences. Arguments in favor of permitting lien stripping include:

- Empirical evidence demonstrates that chapter 13 lien stripping, which the Supreme Court authorized in Nobleman,11 had minimal effect on mortgage credit costs. As a result, permitting chapter 7 debtors to strip liens will have similarly limited consequences.

- Secured lenders do not have an entitlement to future appreciation in the collateral (the "upside of collateral"). Rather, the Bankruptcy Code protects the rights of creditors to the extent of the value of their interest in the collateral.

Arguments against permitting debtors to strip down underwater junior liens include:

- A wholly undersecured junior lien remains a valuable property right, especially during the current upturn of the housing market.

- Stripping-off liens in chapter 11, 12 and 13 cases does not justify it in chapter 7. In these reorganization cases, permitting the debtor to lien-strip represents a quid pro quo given certain creditor protections, such as the requirement that the debtor commit all disposable income. In chapter 7, these protections are absent.

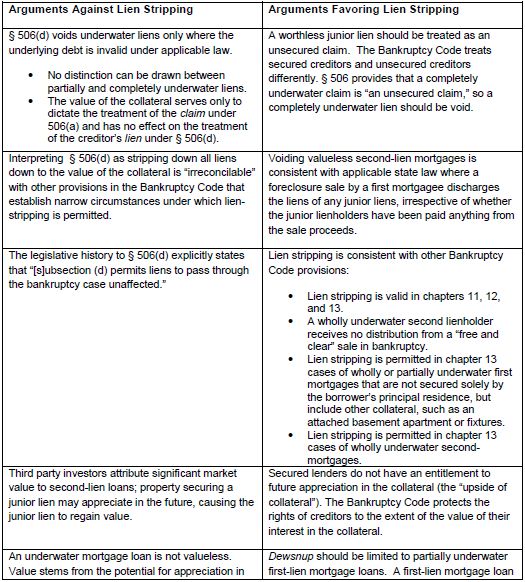

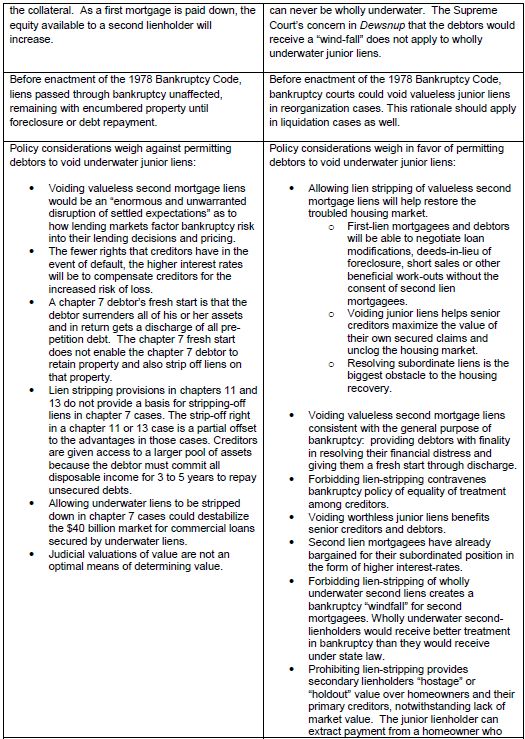

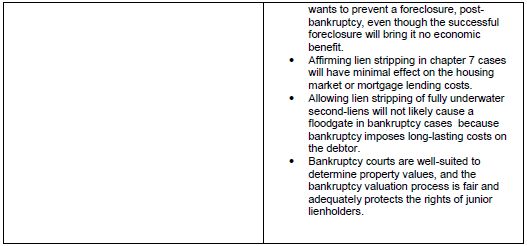

Both sides argue that the structure of the Bankruptcy Code, pre-Code practice, legislative history and policy considerations dictate their result. These arguments are provided in chart form below. Regardless of the outcome, the Supreme Court's decision will have broad ripple effects through the secondary housing market.

Footnotes

1 566 Fed. Appx. 879 (11th Cir. 2014).

2 556 Fed. Appx. 911 (11th Cir. 2014).

3 502 U.S. 410 (1992).

4 See, e.g., Palomar v. First Am. Bank, 722 F.3d 992 (7th Cir. 2013); In re Talbert, 344 F.3d 555 (6th Cir. 2003); Ryan v. Homecomings Fin. Network, 253 F.3d 778 (4th Cir. 2001).

5 Justice Thomas did not participate in the decision.

6 Some amici have argued that Dewsnup was wrongly decided and should be over-ruled. Such amici argue that liens pass through bankruptcy unaffected, but they do so only to the extent not avoided by other bankruptcy code provisions. The amici note that under the Supreme Court's prior rulings, secured creditors must receive the value of collateral available for their claims, but not the collateral itself.

7 735 F.3d 1263 (11th Cir. 2012).

8 For example, section 1111(b)(2) operates "notwithstanding section 506(a)." 11 U.S.C. § 1111(b)(2).

9 The "windfall" argument only applies to an individual debtor; a corporate debtor does not receive a discharge in a liquidation.

10 11 U.S.C. § 1325(a)(5)(B) permits a chapter 13 debtor to "cram down" a secured creditor's claim to the value of the collateral if (1) the plan provides that the creditor will receive the amount of its allowed secured claim and (2) the creditor retains the lien until full payment of the underlying debt or discharge.

11 Nobleman v. American Sav. Bank, 508 U.S. 324 (1993).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.