As of April 1, 2014, California hospitals are subject to a significantly increased risk of being fined when state authorities find deficiencies in their compliance with licensing requirements and other health care-related laws.

In 2006, the California Legislature enacted legislation authorizing the California Department of Public Health (CDPH) to issue administrative penalties if it determined that a licensed hospital's "noncompliance with one or more requirements of licensure has caused, or [was] likely to cause, serious injury or death."1 Initially, the fines for such violations (known as "Immediate Jeopardies" or "IJs") were capped at $25,000, but they were later increased and changed to a three-strikes scheme, such that the maximum fines were $50,000 for the first IJ, $75,000 for the second, and $100,000 for the third or any subsequent violation.2

Between October 2007 and January 2014, CDPH issued 283 such penalties, which totaled $12,835,000. But that was just the warm-up act. Now, hospitals can expect to see increased activity in this area due to new regulations that became effective on April 1, 2014. These regulations, which drastically expand the circumstances in which a penalty may be issued and increase the maximum penalties by another $25,000 each, are complex and confusing, and provide no additional transparency with regard to when a fine might be imposed.

The Regulations Are Seven Years Overdue

When enacting the administrative penalty legislation, the Legislature instructed CDPH to promulgate regulations setting forth criteria for penalty assessment, which must include, at a minimum:

- the patient's physical and mental condition

- the probability and severity of the risk that the violation presents to the patient

- the actual financial harm to patients, if any

- the nature, scope, and severity of the violation

- the facility's history of compliance with related state and federal statutes and regulations

- factors beyond the facility's control that restrict the facility's ability to comply with applicable licensing laws and regulations

- the demonstrated willfulness of the violation

- the extent to which the facility detected the violation and took steps to immediately correct the violation and prevent the violation from recurring.3

However, CDPH was not required to promulgate these regulations before exercising its fining authority. The first 11 administrative penalties issued were publically announced on October 25, 2007, and CDPH has issued between eight and 22 penalties every few months since.4 In each instance, CDPH imposed the maximum penalty regardless of the nature and scope of harm to the patient or any other factor, taking the position that it was not permitted to impose a lesser penalty because there were no applicable regulations despite the statutory language (1) authorizing CDPH to issue fines "up to" the specified amounts, and (2) granting CDPH "discretion to consider all factors when determining the amount of an administrative penalty."5

Over the last seven years CDPH provided absolutely no guidance as to how it determines which incidents warrant administrative penalties; neither has there been any discernible pattern in its fining practices. For example, from July 2007 to May 2010, hospitals self-reported the post-surgical retention of a foreign object 461 times.6 Of those reported incidents, only 28 resulted in an administrative penalty, and a review of those cases suggests that no consistent criteria were applied. To compound matters, CDPH's practice has been to inform a hospital that an Immediate Jeopardy finding will be issued months after conducting a survey, and to assess penalties years after the incident occurred. Thus, hospitals have been in constant limbo, waiting to find out if or when a penalty might be assessed for alleged violations of licensure requirements.

Now that the final regulations have taken effect,7 facilities might expect to have a clear roadmap of the circumstances that will result in a penalty being issued, and the approximate amount of any such penalty. In reality, the final regulations raise many more questions than they resolve.

New Regulatory Criteria: Vague, Ambiguous and Confusing

Along with the issuance of the final regulations, the maximum penalties for Immediate Jeopardies have increased by $25,000 (i.e., up to $75,000, $100,000 and $125,000 for the first, second, and third IJ, respectively), and CDPH may begin issuing penalties of up to $25,000 for non-minor violations that do not rise to the level of an Immediate Jeopardy.8 The determination of an administrative penalty amount requires a number of intricate steps. In brief, those steps are:

- Calculate the "Initial Penalty" by multiplying the maximum statutory penalty by a percentage amount obtained from a "Severity/Scope of Noncompliance" matrix;

- Apply "adjustment factors" to the Initial Penalty to derive the "Base Penalty" (which may be higher than the statutory maximum); and

- Apply additional "adjustment factors" to the Base Penalty to derive the "Final Penalty."

- Assess the lesser of the Final Penalty or the statutory maximum.

Each of these steps involves multiple vaguely defined decision points that will be subject to interpretation and dispute. In response to concerns about the significant risk that the new regulatory scheme will be inconsistently applied, CDPH has stated that it "intends to implement a universal electronic penalty assessment tool that will be used by all District Offices and surveyor staff ... which will provide transparency and consistency throughout the state."9 However, in all likelihood, there will be variations in the manner in which the analysis is conducted by different District Offices, which will lead to widely varying outcomes, both in the types of situations in which a fine is levied, and the amount of the fines that are imposed.

Levels of Severity

The first step in applying the new criteria is to determine the "severity of the deficiency."10 There are six "Severity Levels," not including "minor violations," which the Legislature explicitly excluded from the penalty scheme but left up to CDPH to define. Given that Immediate Jeopardies are grounded in an alleged failure to comply with a "requirement of licensure," one would expect that "minor violations" would have a similar touchstone. To the contrary, a "minor violation" has been defined as: "Any violation of law relating to the operation or maintenance of a hospital that the department determines has only a minimal relationship to the health or safety of hospital patients" (emphasis added). This definition is both over-inclusive and significantly limiting. It is over-inclusive because it applies to all "laws relating to the operation or maintenance of a hospital," which is certainly more expansive that the "requirements of licensure." It is limited because it gives CDPH the room to assert that any violation has "more than a minimal relationship to the health or safety of hospital patients." Thus, the fact that no administrative penalties are permitted for "minor violations" will not impede CDPH's fining authority to any measurable extent.

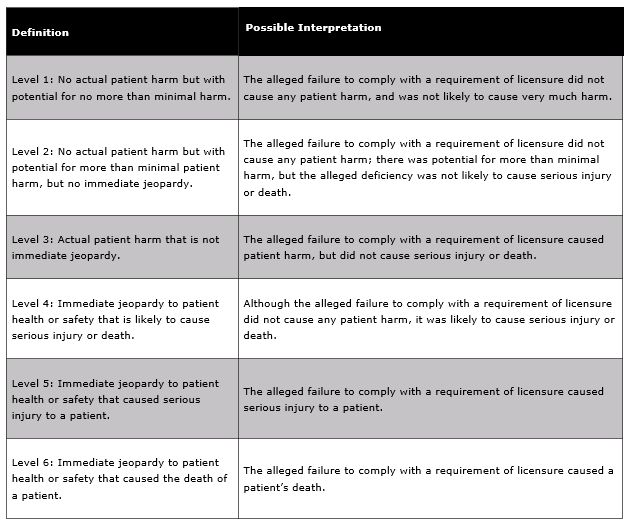

As to the six Severity Levels for non-minor violations, the categories for the degree of "severity of the deficiency"11 are convoluted and confusing. In the table that follows, we provide a possible interpretation of each Severity Level.

After defining each of the six Severity Levels, the regulation explicitly states that the first two criteria required by the Legislature (the patient's physical and mental condition, and the probability and severity of the risk that the violation presents to the patient) "shall be considered" in determining the level of severity.12 Since both of those factors are actually included in each of the Severity Level definitions, the purpose of the follow-up provision is not clear.

Scope of the Noncompliance

In promulgating the final regulations, CDPH replaced its initially proposed "extent of noncompliance" measure, which "would assess the extent to which a hospital deviated from hospital licensure requirements," with a "scope of the noncompliance" measure, which measures "the scope to which the patients have been affected by, or the number of staff or locations involved in, the noncompliance."13 The three "scope" categories are:

- Isolated (one or a very limited number of patients affected/staff involved; situation occurred occasionally, or in a very limited number of locations)

- Pattern (more than a very limited number of patients affected/staff involved; situation occurred in several locations or repeatedly), and

- Widespread (situation was pervasive; represents a systemic failure that affected or could affect many/all of the hospital's patients).

CDPH has stated that its final "Scope/Severity Matrix" is "modeled on the federal long-term care assessment matrix used by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services," and that its intent "is to assess the scope level of a noncompliance in a manner that is consistent with the federal assessment process."14 Multiple commenters took issue with the application of a long-term care approach in an acute care setting stating, for example, that the underlying federal model "has proven hugely defective and ineffective in promoting quality and change."15 However, CDPH consistently asserted that the model was effective and would support consistency in assessing penalties.

The Matrix for Determining the Initial Penalty

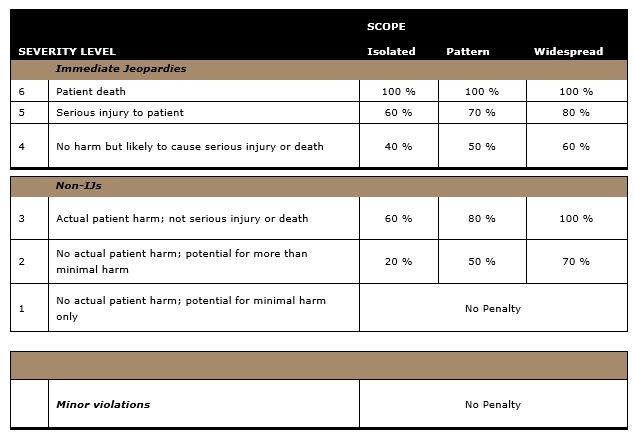

Once the Level of Severity and Scope of Noncompliance are identified, CDPH will consult its Matrix to determine the multiplier that is to be used in calculating the Initial Penalty. The Matrix is as follows:

Thus, if a non-IJ violation is determined to be a Severity Level of 2 with an Isolated Scope, the Initial Penalty will be $5,000 ($25,000 x 20 percent). At the other end of the spectrum, if a "third" Immediate Jeopardy penalty is based on a determination that the violation caused the patient's death, the Initial Penalty will be $125,000 (100 percent of the maximum statutory amount).

Although the regulations are "new," the regulatory structure is not; CDPH has been issuing IJ penalties since October 2007. Thus, CDPH intends to continue relying on the history of those penalties in determining whether or not an Immediate Jeopardy is a first, second, etc. penalty. Comments to the proposed regulations included that such a decision would violate due process, because the prior penalties were not issued on the basis of these regulations. However, CDPH did not make any changes to the final regulations as a result of those comments.

In addition, if a facility has been issued IJ administrative penalties in the past, a newly issued penalty may be designated as a "first administrative penalty" (and thus be subject to the lower fines), if the date the violation occurred is more than three years from the date of any prior Immediate Jeopardy for which a penalty was issued, and if the hospital was in "substantial compliance" with both state licensing requirements and the Medicare Conditions of Participation. For the purpose of the regulations, "substantial compliance" means that "any identified deficiencies pose no greater risk to patient health and safety than the potential for causing minimal harm."16

Adjusting the Initial Penalty

The Initial Penalty may be adjusted downward by as much as 5 percent or upward by as much as 21 percent, based on four specific factors: the patient's physical and mental condition post-incident; whether the patient suffered any financial harm; factors beyond the hospital's control, limited to circumstances that are caused by a disaster or emergency; and whether the alleged violation is determined to be "willful."

- Patient's Physical and Mental Condition

As noted above, the determination of the Level of Severity of an alleged deficiency includes (not once, but twice) "the patient's physical and mental condition," which is one of the eight assessment criteria required by the Legislature. That factor is to be considered yet a third time when adjusting the Initial Penalty. Specifically, for the two Severity Levels that encompass patient harm,17 the Initial Penalty is to be adjusted upward by 10 percent if the harm resulted in "a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of a patient, or the loss of bodily function, if the impairment or loss lasts more than seven days or is still present at the time of discharge from the hospital, or the loss of a body part."18 If an impairment or loss of bodily function lasts more than three days (but, presumably, less than eight days), the Initial Penalty will be adjusted upward by only 5 percent rather than 10 percent.19

Although not clearly identified as such, this terminology is pulled from the definition of a "Serious Disability" set forth in the statute governing self-reporting of adverse events.20 Thus, in drawing these distinctions, CDPH appears to be attempting to assess a graduated penalty based on the severity of the harm that has occurred. The actual operation of this provision will be problematic, as it sets up this unworkable ladder:

- Level 3: actual harm that is not serious injury or death

- Level 3 plus: actual harm that is not serious injury or death, but is a Serious Disability

- Level 5: serious injury

- Level 5 plus: serious injury that is also a Serious Disability.

With regard to Severity Level 3, it defies logic to assert that there will be actual patient harm that is not an Immediate Jeopardy (thus, not "serious injury or death"), but at the same time is a Serious Disability. As to Severity Level 5, there is quite a bit of room for interpretation in drawing a distinction between a serious injury and a Serious Disability.

- Actual Financial Harm

Another criterion required by the Legislature is whether there was actual financial harm to any patient.21 CDPH thus has included it as an adjustment factor, but has drastically restricted its impact on the overall calculation. Thus, if an alleged violation caused a patient "actual financial harm," which means "concrete financial loss for medical costs incurred by a patient, where the loss was not covered or reimbursed by health insurance,"22 the Initial Penalty will be adjusted upward by one percent.23

- Factors Beyond the Hospital's Control

The Legislature also specifically directed CDPH to consider whether there were "factors beyond the facility's control that restrict the facility's ability to comply" with applicable licensing laws and regulations."24 A fair reading of this provision would give hospitals some relief from the assessment of administrative penalties when the circumstances underlying the alleged deficiency were unforeseeable or could not be guarded against. For example, if an employee who is a licensed provider deviates from the acceptable scope of practice to an extent that could not be imagined (as has often been the case for past administrative penalties), such actions are clearly beyond control by the hospital.

Rather than recognizing that there are many different circumstances that are truly uncontrollable, CDPH elected to limit the scope of this factor to disaster or emergency circumstances only. Thus, IF and ONLY IF: (1) a disaster were to occur; (2) the hospital previously had developed and maintained legally required disaster and emergency programs; (3) such program were implemented during a disaster; and (4) despite all such efforts the disaster or emergency restricted the hospital's ability to comply with licensure requirements, THEN CDPH will decrease the amount of the Initial Penalty by 5 percent.

- Willful Violations

The Legislature also included as a required factor "the demonstrated willfulness of the violation."25 Again, the plain language of this provision calls for an interpretation that recognizes the complex nature of health care, and the human factors attendant to operation of a hospital. Again, however, CDPH has taken the more draconian approach, using this factor to turn the statute into a strict-liability, medical-error statute, rather than a balanced set of rules designed to protect patient safety.

Specifically, the regulations define "willfully," as "that the person doing an act or omitting to do an act intends the act or omission, and knows the relevant circumstances connected with the act or omission," and a "willful violation" as a situation in which the hospital, "through its employees or contractors, willfully commits an act or makes an omission with knowledge of the facts, which bring the act or omission within the deficiency that is the basis for the administrative penalty."26 In such circumstances, the Initial Penalty will be increased by 10 percent. Unfortunately, these definitions are written so broadly that this adjustment factor can be applied against a hospital every time that a hospital employee takes an action or refrains from acting and the result is an adverse outcome.

The Base Penalty

After each of the adjustment factors listed above are applied to an Initial Penalty, the resulting calculation is denominated the "Base Penalty." Depending on the starting point, if the Initial Penalty has been adjusted upwards, it is possible for the Base Penalty to be greater than 100 percent of the statutory maximum. The regulations explicitly permit such a circumstance, "so long as the final penalty does not exceed the statutory maximum."

Adjusting the Base Penalty

The Base Penalty for NON-Immediate Jeopardies may be adjusted downward by as much as 25 percent or upward by 5 percent, based on whether the violation was corrected immediately, as well as the hospital's history of compliance or non-compliance with state licensure requirements and federal Medicare Conditions of Participation in the prior three years. The Base Penalty for Immediate Jeopardies may be adjusted downward or upward by 5 percent based on the hospital's compliance history.

- Immediate Correction

The Legislature's required criteria included the extent to which the facility detected the violation and took steps to immediately correct the violation and prevent the violation from recurring. The statute does not limit the application of this factor in any way, and it arguably should apply to all alleged deficiencies. However, CDPH has limited this factor to violations that "did not constitute immediate jeopardy or result in the death of the patient" (which is redundant, because a patient's death would be categorized as an immediate jeopardy). In such non-IJ circumstances, the Base Penalty may be adjusted downward by 20 percent if all of the following apply:

- The hospital identified and corrected the noncompliance before it was identified by the department. Thus, the incident must be discovered by the hospital, rather than by a CDPH surveyor.

- The hospital completed all corrective action to prevent recurrence within 10 calendar days of the date the noncompliance was identified, and detailed documentation of such actions. Note that the regulations do not set forth any guidance regarding when a noncompliance is "identified;" CDPH is likely to take the position that such identification is immediate once any adverse outcome is discovered, whether or not the facility is able to determine the exact cause of the outcome without first conducting an investigation.

- The hospital reported the incident as required before the incident was identified by CDPH.

- "A penalty was not imposed for a repeat deficiency that received a penalty reduction under this article within the 12-month period prior to the date of violation." This appears to indicate that any noncompliance that recurs within 12 months cannot receive this reduction, if the reduction was applied to an initial administrative penalty.

- History of Compliance with Related State and Federal Laws

Yet another of the Legislature's enumerated criteria is "the facility's history of compliance with related state and federal statutes and regulations."27 The regulations state that such compliance history refers to a hospital's "record of compliance with licensure requirements under [HSC], and the regulations adopted thereunder, and with federal laws that set forth the conditions of participation for hospitals in the Medicare program, for a period of three years prior to the date the administrative penalty is issued."28 For both IJ and non-IJ penalties, the base penalty will be adjusted downward by 5 percent if the hospital did not have any state or federal deficiencies rising to a Severity Level 3-6 in the prior three years, and will be adjusted upward by 5 percent if there were three or more repeat deficiencies at Severity Levels 2-6 in the prior three years.

The Final Penalty

Once all of the adjustments are made to the Base Penalty, the Final Penalty will be the lesser of (1) the penalty with all adjustments or (2) the statutory maximum. Based on all of these factors, we have determined that the range of possible penalty assessments is between $4,513 and $125,000. In addition, if an administrative penalty would cause a financial hardship for a small and rural hospital, the hospital may request that the penalty be paid over an extended period of time, or that the penalty be reduced, or both.

Appealing a Penalty

The strict time deadline for appealing the assessment of an administrative penalty has not changed; a hospital that disputes a finding of a deficiency or the imposition of a penalty may request a hearing to challenge CDPH's decision.29 All such appeals must be submitted within 10 working days of notification of the penalty.30 Penalties that are appealed do not have to be paid until after the hearing process is complete, and only if CDPH prevails. We have handled and are handling many appeals of these penalties, and have been successful in getting them dismissed or significantly reduced.

Conclusion

In the last seven years, some IJs have resulted in administrative penalties and others have not, and there has been no discernible distinction between the two groups. These new regulations simply fail to clarify the administrative penalty process: they provide no guidance as to what types of IJ and non-IJ deficiencies will trigger a penalty; they promulgate a complicated penalty matrix for determining the amount of any fine; and they create a whole new set of confusing issues. What is crystal clear, however, is that CDPH has no intention of letting up on its drive to raise money by penalizing hospitals under this regulatory scheme. The forecast for hospitals is bleak, as the regulations are designed to result in the now-increased maximum penalties for alleged IJs, and the likelihood of non-IJ penalties being assessed also is very high.

Now more than ever, California hospitals need knowledgeable and experienced counsel to determine whether to appeal and on what basis to challenge these administrative penalties. When the possibility of administrative penalties are noted by CDPH, during or after a survey, California hospitals need to act quickly to assess the facts and to consider filing an appeal should fines be imposed.

Footnotes

1 Senate Bill 1312; California Health and Safety Code (HSC) § 1280.1.

2 Id. The impetus for the increased fines and "three-strikes" approach was CDPH's "belief" that the "existing penalty amount [was] too low." SB 541 Bill Analysis: Assembly Committee on Health, Hearing (Aug. 18, 2008).

3 HSC § 1280.3(b).

4 CDPH publishes IJ penalties on its Web site at: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/certlic/facilities/Pages/Counties.aspx.

5 HSC § 1280.1(d).

6 This analysis is based on the data available on the Health Facilities Consumer Information system Web site and in the 2567 forms published on CDPH's Web site.

7 22 California Code of Regulations (CCR) §§ 70951, et seq., for General Acute Care Hospitals, and §§ 71701, et seq. for Acute Psychiatric Hospitals.

8 Id.

9 Addendum II to Final Statement of Reasons, Department Response to Comment 2-5 (October 15, 2013).

10 22 CCR § 70954(b).

11 A "deficiency" means "a licensee's failure to comply with any law relating to the operation or maintenance of a hospital as a requirement of licensure under" applicable licensing laws and regulations. 22 CCR § 70952(a)(2).

12 22 CCR § 70954(2).

13 Addendum II to Final Statement of Reasons, Department Commentary on Section 70954(c) (October 15, 2013).

14 Id.

15 Addendum IV to Final Statement of Reasons, Comment 2.22 (October 15, 2013).

16 22 CCR § 70952(a)(6).

17 Level 3–actual harm, not serious injury or death, and Level 5–serious injury.

18 22 CCR § 70955(a)(1)(A).

19 Id.

20 HSC § 1279.1.

21 HSC § 1280.3(b)(3).

22 22 CCR § 70952(a)(1).

23 22 CCR § 70955(a)(2).

24 HSC § 1280.3(b)(6).

25 HSC § 1280.3(b)(7).

26 22 CCR §§ 70952(7) and (8).

27 HSC § 1280.3(b)(5).

28 22 CCR § 70957(a)(2).

29 HSC § 1280.3(f).

30 Id.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.