- within Government, Public Sector, Insurance and Coronavirus (COVID-19) topic(s)

In Mohsenzadeh v. Lee (decided March 19, 2014), the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia held that the Patent Term Adjustment (PTA) statute does not provide PTA to a divisional application when the USPTO takes longer than 14 months to issue a Restriction Requirement in the parent application. While this decision is not surprising, it is a reminder that applicants may have to choose between the protections offered to divisional applications by 35 USC § 121 and the possible impact on enforceable patent term of filing related applications in series rather than in parallel.

The Patents at Issue

The patents at issue are U.S. Patent 8,352,362 and U.S. Patent 8,401,963, directed to methods of transferring resources from one entity to another, and related methods. These two patents stem from divisional applications of U.S. Patent 7,742,984.

The patent applications that issued as the '362 and '963 patents were filed on January 8, 2010. The '362 patent was issued on January 8, 2013, and the '963 patent was issued on March 19, 2013. The USPTO did not award any PTA to these patents.

The USPTO Delay at Issue

I first wrote about this case shortly after the complaint was filed. As I explained in that article, the patent application that issued as the parent '984 patent (the "parent application") was filed July 6, 2001 and issued June 22, 2010. The USPTO awarded 2,104 days PTA to the '984 patent, including 1476 days for the USPTO's failure to issue a first Office Action within 14 months of the application's filing date.

The first Office Action issued in the parent application was a Restriction Requirement mailed September 21, 2006, 1476 days after 14 months after the application was filed. Mr. Mohsenzadeh argued that the PTA calculations for the '362 and '963 patents should include the 1476 days of USPTO delay in issuing the Restriction Requirement in the parent application, because it is that Restriction Requirement that necessitated the filing of the applications that issued as the '362 and '963 patents.

The District Court Decision

The district court granted summary judgment in favor of the USPTO (and against Mr. Mohsenzadeh) for two reasons:

First, the Court holds that the language of the PTA Statute unambiguously applies to only one patent application—providing PTA for delays that occurred during the prosecution of the application from which the patent issued.

Alternatively, the Court holds that to the extent that the language of the PTA Statute is ambiguous, the USPTO's longstanding interpretation of the statute, as manifested in 37 C.F.R. §§ 1.702,1.703, and 1.704(c)(12), is reasonable and entitled to some deference

The PTA Statute

The statute at issue is the basic PTA statute, 35 USC § 154(b):

(b) Adjustment of Patent Term.—

(1) Patent term guarantees.—

(A) Guarantee of prompt patent and trademark office

responses.— Subject to the limitations under paragraph (2),

if the issue of an original patent is

delayed due to the failure of the Patent and Trademark Office

to—

(i) provide at least one of the notifications under section 132 or

a notice of allowance under section 151 not later than 14 months

after—

(I) the date on which an application was

filed under section 111 (a); or

(II) the date of commencement of the national stage under section

371 in an international application;

(ii) respond to a reply under section 132, or to an appeal taken

under section 134, within 4 months after the date on which the

reply was filed or the appeal was taken;

(iii) act on an application within 4 months after the date of a

decision by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board under section 134 or

135 or a decision by a Federal court under section 141, 145, or 146

in a case in which allowable claims remain in the application;

or

(iv) issue a patent within 4 months after the date on which the

issue fee was paid under section 151 and all outstanding

requirements were satisfied,

the term of the patent shall be extended 1 day for each day after

the end of the period specified in clause (i), (ii), (iii), or

(iv), as the case may be, until the action described in such clause

is taken.

Mr. Mohsenzadeh argued that the plain language of statute supported his position because the issue of his original patents—the '362 and '963 patents —was delayed due to the USPTO's failure to issue an Office Action within 14 months after the date on which an application—the parent application—was filed.

The district court disagreed, and determined that the statute's "one-to-one correspondence for the terms 'an original patent,' 'an application' and 'the patent'" indicated that "the plain language of the PTA Statute applies to only one patent." The court also noted that when the statute does invoke earlier applications, it does so more clearly and explicitly, such as when 35 USC 154(a)(2) defines the 20-year term of a patent with reference to the filing date of "an earlier filed application" to which priority is claimed.

The USPTO Rule at Issue

The district court also determined that 37 CFR § 1.704(c)(12) was a reasonable interpretation of the PTA statute that was entitled to Skidmore deference. This rule states:

(c) Circumstances that constitute a failure of the applicant to

engage in reasonable efforts to conclude processing or examination

of an application also include the following circumstances, which

will result in the following reduction of the period of adjustment

set forth in § 1.703 to the extent that the periods are not

overlapping:

*****

(12) Further prosecution via a continuing application, in which

case the period of adjustment set forth in Sec. 1.703 shall not

include any period that is prior to the actual filing date of the

application that resulted in the patent.

(This rule originally was set forth at 37 CFR § 1.704(c)(11), and was renumbered to 37 CFR § 1.704(c)(12) with the PTA rule changes published August 12, 2012, with an effective date of September 17, 2012.)

The court evaluated the USPTO regulations under four factors:

- whether the regulations were a contemporaneous construction of a statute by the persons charged with the responsibility implementing the statute

- the thoroughness evident in its consideration and the validity of its reasoning

- its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements

- whether it reflects agency-wide policy.

In deciding to uphold the rule, the court reasoned that it was adopted essentially contemporaneously with the statute and has been consistently applied without challenge for thirteen years.

The Choice Between § 121 And Enforceable Patent Term

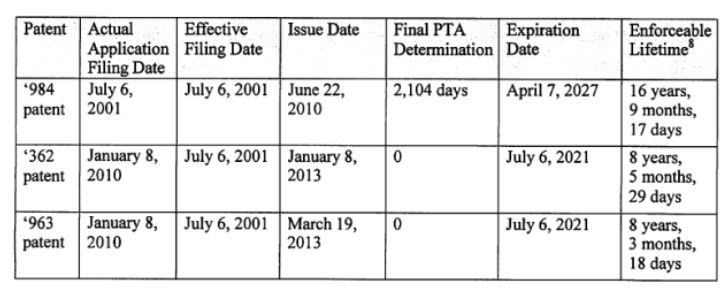

The district court decision includes this chart comparing the enforceable patent terms of the patents at issue:

As reflected in this chart, even though all of the patents had the same 20-year term, the '984 patent had a much longer enforceable term because of the PTA award and also because the divisional patents were filed several years later. (Indeed, as noted by the court, the divisional applications were filed several years after the Restriction Requirement was issued). The district court reasoned that awarding PTA to only the first patent even when the delay at issue related to the Restriction Requirement that led to the filing of the other two patents "demonstrates a statutory scheme for divisional patents which serves important public policy goals."

While I do not necessarily disagree with the court's interpretation of the statute, its discussion of the choices and trade-offs an applicant can make when deciding how to structure its patent applications seems to presume a level of reasonableness, uniformity, and predictability in USPTO restriction requirement and obviousness-type double patenting practice that simply does not exist.

For example, the court states:

According to the court, inventors are "free" to choose between "broadly" filing claims in a single application to obtain "the protection of both the safe harbor [of § 121 against obviousness-type double patenting rejections] and the priority date of the parent," and risking "that the divisional applications may ultimately receive shorter enforceable patent terms." The court reasons that "this set of trade-offs is manifestly in the public interest" because "[i]t offers inventors fair and valuable protections while simultaneously incentivizing the filing of narrowly tailored applications that do not unduly burden the USPTO's examination process."

Oh, the poor USPTO! What about all those excess claim fees it collected before the Restriction Requirement was issued?

The court criticized Mr. Mohsenzadeh for failing "to take responsibility for the fact that he submitted a broad patent application with four patentably distinct inventions." Indeed, the court interpreted the relevant prosecution history as follows:

Any applicant who has had a claim set that did not trigger any unity of invention rejections in a PCT or EP application, but was restricted into multiple inventions by the USPTO will understand the lack of understanding that this comment belies!

In any event, this decision confirms that applicants who are concerned about maximizing the enforceable term of claims that are likely to be subject to a restriction requirement may want to weigh the risks and benefits of waiting for a Restriction Requirement to be issued (to achieve the protections of § 121) versus filing voluntary "divisional"-type applications in parallel.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.