- within Insurance, Real Estate and Construction and Consumer Protection topic(s)

Marked by leadership changes, high-profile trials, and shifting priorities, 2013 was a turning point for the Enforcement Division of the Securities and Exchange Commission (the "SEC" or the "Commission"). While the results of these management and programmatic changes will continue to play out over the next year and beyond, one notable early observation is that we expect an increasingly aggressive enforcement program.

I. Introduction

Since her swearing in as Chair of the SEC on April 10, 2013, former United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York Mary Jo White has repeatedly emphasized the importance of a robust Enforcement Division. As Chair White told The Wall Street Journal in June: "The SEC is a law-enforcement agency. You have to be tough. You have to try to send as strong a message as you can, across as broad a swath of the market as you regulate."1 That is likely why, when choosing the Enforcement Division director, White turned to George Canellos (already Acting Director of the Division) and Andrew Ceresney, two former federal prosecutors from her days as United States Attorney.2 Similarly, beyond the home-office, former federal prosecutors have been appointed to lead some of the SEC's regional offices. In fairness, the trend towards a quasi-criminal enforcement regime began under the SEC's prior leadership, when then-SEC Chairman Mary Schapiro appointed Robert Khuzami to head the Enforcement Division in the aftermath of the Madoff scandal; now, it appears the change of emphasis is here to stay.

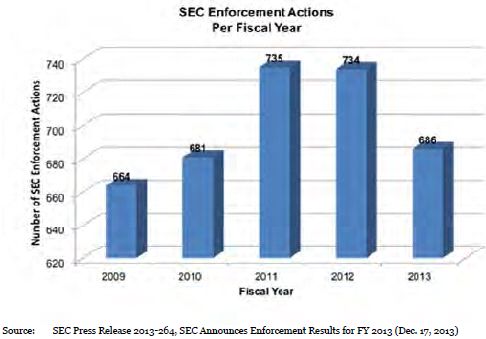

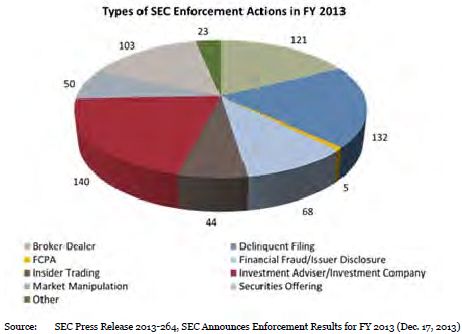

As illustrated in the chart below, the SEC filed 686 enforcement actions in FY2013, a decrease from FY2011 and FY2012, when the SEC filed 735 and 734 enforcement actions, respectively. Of these 686 cases, 132 were delinquent filing actions.3 Consequently, FY2013, based on the SEC's own statistics, appears to be the Division's least productive year since 2006. However, one should not take too much from these numbers, as the SEC also announced that there is a 20 percent increase in the number of formal orders of investigations issued by the Enforcement Division.4

The distribution of cases among the Enforcement Division's filing categories remained relatively stable in 2013. Only three categories of SEC actions showed an increase in the number of filings — actions related to (i) delinquent filings, (ii) market manipulation, and (iii) securities offerings. Meanwhile, filings in all other categories decreased, with the number of Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA") actions experiencing the steepest decline, from 15 actions in FY2012 to five in FY2013, and the number of insider trading actions dropping from 58 to 44.

Notwithstanding that the SEC filed fewer cases in FY2013, it obtained record civil penalties, disgorgement, and prejudgment interest. According to the SEC, "[t]he $3.4 billion in disgorgement and penalties resulting from [the actions concluded in FY2013] is 10 percent higher than FY2012 and 22 percent higher than FY2011, when the SEC filed the most actions in agency history."5

More than the figures, however, 2013 may be remembered for the high-profile trials and cases the SEC brought or concluded throughout the year. Whether winning big or losing big, the SEC demonstrated that the Enforcement Division is not afraid to "aggressively deploy litigation resources to maximize the deterrent impact of enforcement actions."

In this memorandum, we address these cases, as well as the key policy and priority shifts announced by the SEC's new leadership in 2013.6

II. New Enforcement Division Priorities: A "Broken Windows" Policy

The Enforcement Division's key priorities have begun to move away from pursuing securities violations that contributed to the financial crisis and which have for several years consumed a substantial percentage of the Enforcement Division's resources. Indeed, in a speech on October 9, 2013, Chair White explained the Commission's current thinking as follows:

- We want you to start thinking that every issue you face in the SEC's space is a very important one. One of our goals is to see that the SEC's enforcement program is—and is perceived to be—everywhere, pursuing all types of violations of our federal securities laws, big and small.

- The underpinning for this strategy was outlined in an article, which many of you will have read or heard of, titled, 'Broken Windows.' The theory is that when a window is broken and someone fixes it—it is a sign that disorder will not be tolerated. But, when a broken window is not fixed, it 'is a signal that no one cares, and so breaking more windows costs nothing.'

- The same theory can be applied to our securities markets—minor violations that are overlooked or ignored can feed bigger ones, and, perhaps more importantly, can foster a culture where laws are increasingly treated as toothless guidelines. And so, I believe it is important to pursue even the smallest infractions. Retail investors, in particular, need to be protected from unscrupulous advisers and brokers, whatever their size, and the size of the violation that victimizes the investor.7

Chair White then laid out the key ways in which the SEC is now seeking to pursue this goal:

- Leveraging the strength of the SEC's exam program, incentivizing individuals to step forward through the whistleblower and cooperation programs, collaborating more with other regulatory agencies, and increasing the use of technology in investigations;

- Focusing on deficient gatekeepers, whom the SEC views as responsible for self-policing the markets;

- Looking for the "broken windows" in our markets and not overlooking small violations or violations that do not involve fraud; and

- Prioritizing big and high-profile cases to send a strong message of deterrence to the industry and boosting the confidence of investors.8

While none of these priorities are new, the emphasis is subtly changed. Clearly, there are no areas of the securities industry that can expect to be free of enforcement oversight, and Chair White has been cautious about singling out any one area for attention. But based on the Enforcement Division's statements and track record in 2013, certain areas of focus remain apparent. Those include accounting and other financial reporting fraud; gatekeepers (including, particularly, auditors and lawyers); insider trading; compliance programs at broker-dealers and investment advisers; and the FCPA. These and other issues will be explored in this update.

III. Significant Trials

We begin with a review of the Enforcement Division's 2013 trial record. Despite the apparent push by Chair White to bring more cases to trial (discussed at greater length below), the SEC's trial record in 2013 left something to be desired. Although the Commission won a major victory in August against Fabrice Tourre, its 2013 trial record was also marred by several losses.

The case against Fabrice Tourre, a former Vice President with Goldman, Sachs & Co. ("Goldman"), was the Commission's most significant trial victory in 2013. In April 2010, the SEC sued both Tourre and Goldman in a civil injunctive action, alleging that they committed fraud in connection with the structuring and sale of a collateralized debt obligation ("CDO"). While Goldman settled the allegations against it, without admitting or denying wrongdoing, by agreeing to pay a $535 million civil penalty and $15 million in disgorgement, Tourre opted for trial. After a two-week trial, the jury found Tourre liable on six of seven counts of fraud. To some, Tourre had, rightly or wrongly, become the face of the financial crisis. Consequently, the victory was undoubtedly a considerable relief to the SEC, which had tasked its chief litigator with personally trying the case. Since the Tourre trial, however, the news has been far less positive for the SEC.

In October, the SEC was handed a high-profile defeat in court when billionaire entrepreneur Mark Cuban was found not liable for insider trading in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Texas. The SEC alleged that Cuban engaged in insider trading when he sold his stake in a Canadian internet company after the company's CEO, Guy Faure, informed Cuban that the company was planning a private offering in public equity (PIPE), which would result in his stock being diluted.9 Allegedly, Cuban sold his stock to avoid a $750,000 loss. The case largely boiled down to the interpretation of a single unrecorded phone call between Cuban and Faure. But while Cuban testified at trial and adamantly defended himself, Faure, who lives in Canada, refused to travel to Dallas to testify, forcing the SEC to introduce his testimony via videotape. The jury ultimately rejected the SEC's claims, apparently believing Cuban's version of events. Against the backdrop of the government's war on insider trading over the last few years, the Cuban case attracted significant public attention and marked a high-profile trial loss for the Commission.

Shortly after the Cuban loss, the SEC suffered another trial defeat in its long-running dispute with Steve Kovzan, the CFO of Kansas-based government website contractor NIC, Inc.10 In January 2011, the SEC filed a civil injunctive action against NIC, Kovzan, and three other NIC executives alleging that the defendants failed to disclose $1.18 million in executive perks, including use of a private company jet.11 NIC and the other charged executives settled, but Kovzan put the SEC to the task of proving its case in court. On December 2, after a three-week trial in the United States District Court for the District of Kansas, the jury found Kovzan not liable on all 12 of the SEC's claims, including fraud and books and record charges.

In December, the SEC lost again in SEC v. Jensen.12 The SEC filed suit in July 2011 against Peter Jensen and Thomas Tekulve Jr., the former CEO and CFO, respectively, of Basin Water Inc., a company that remediates contaminated water. The SEC alleged that Jensen and Tekulve improperly included revenue from six sham transactions in Basin Water's SEC filings. After a nine-day bench trial, Judge Manuel L. Real of the United States District Court for the Central District of California found the defendants not liable on each claim, stating "[n]o documentary evidence or witness testimony presented at the trial tended to show that any of the transactions were shams," and that "there were valid economic justifications for all six of the transactions."13

And the trial losses have continued in early 2014. On January 7, after a two-day bench trial, Judge William Duffey, Jr. of the United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia rejected the SEC's claims against Ladislav "Larry" Schvacho, finding him not liable for insider trading. Allegedly, Schvacho traded stock based on material nonpublic information about Comsys IT Partners Inc. ("Comsys"), which the SEC claimed was provided to him by Comsys' CEO, Larry L. Enterline, a close friend and business associate of Schvacho.14 At trial, the SEC relied on circumstantial evidence of communications and meetings between Schvacho and Enterline, but Judge Duffey found such reliance undermined by Enterline's "unqualified testimony" that he did not give Schvacho inside information. The court found Enterline to be a credible and truthful witness and emphasized that, despite having brought the case to trial, the SEC did not even attack Enterline's testimony or credibility.15

While it is dangerous to draw broad conclusions from the small number of trials handled by the Enforcement Division every year, of which these are just a sample, this track record could certainly embolden defendants considering trial instead of settlement. The SEC's recent trial losses have come in both federal court and administrative proceedings, in bench trials and jury trials, and in complex financial trials and straight-forward insider trading trials. In short, defendants have won in a wide range of cases, giving the defense bar cause to feel optimistic in resisting SEC charges in the future.

What is far less clear is whether the SEC's mixed trial record will cause the Enforcement Division to rethink how it decides which cases to settle and which ones to take to trial. In light of the aggressive policy statements by Chair White and certain of her staff, it does not appear that the SEC is about to back down or bring fewer cases to trial. But if trial losses continue, changes may not be far behind. Whether that would mean being more selective about the cases the SEC chooses to bring, bringing cases to trial faster, or implementing more structural changes about the way the SEC investigates or litigates cases remains to be seen.

One statistic we will be watching in the coming year is whether the SEC will decide to bring more cases administratively rather than in federal court. The argument for bringing more cases administratively, in the post-Dodd-Frank era, is that the SEC may have more success administratively than in federal court because it is in a friendly forum where the procedural and evidentiary strictures either do not apply or are applied more liberally.

To read this Review in full, please click here.

Footnotes

1 Where the SEC Action Will Be: Interview with Mary Jo White, Wall St. J., June 23, 2013.

2 On January 3, Canellos announced that he intends to step down as co-Director of the Enforcement Division, leaving Ceresney as the sole Director. SEC Press Release, Enforcement Co-Director George Canellos to Leave SEC, Rel. No. 2014-1 (Jan. 3, 2014).

3 SEC Press Release, SEC Announces Enforcement Results for FY 2013, Rel. No. 2013-264 (Dec. 17, 2013).

4 Id.

5 Id.

6 Id.

7 Mary Jo White, Chair, Remarks at the Securities Enforcement Forum (Oct. 9, 2013), available at http://www.sec.gov/News/Speech/Detail/Speech/1370539872100 (footnotes and citations omitted).

8 Id.

9 Ben Protess & Lauren D'Avolio, Jury Rules for Mark Cuban in Setback for S.E.C., N.Y. Times, Oct. 16, 2013.

10 SEC v. Kovzan, No. 11-cv-2017-JWL-KGS (D. Kan. filed Jan. 12, 2011).

11 See SEC Press Release, SEC Charges Government Website Provider and Four Executives With Failure to Disclose CEO Perks, Rel. No. 2011-8 (Jan. 12, 2011).

12 SEC v. Jensen, No. CV-11-5316-R (C.D. Cal. Dec. 10, 2013).

13 Id. at *29.

14 SEC Press Release, SEC Charges Close Friend of Staffing Company CEO with Insider Trading Around Acquisition, Litig. Rel. No. 22423 (July 25, 2012).

15 SEC v. Schvacho, No. 1:12-cv-2557-WSD (N.D. Ga. Jan. 7, 2014).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.