By Yves Botteman* and Agapi Patsa

Almost 10 years after their formal introduction into EU competition legislation, commitment decisions appear to have become the European Commission's enforcement tool of choice when resolving abuse of dominance cases. This article explores the reasons underlying the European Commission's increasing reliance on commitments to conclude Article 102 TFEU investigations and analyses the detrimental effects that a commitment-based enforcement policy may have on EU competition law. The article concludes that time may be ripe for the European Commission to introduce a more comprehensive legal framework for the use of commitment decisions, in order to ensure the more sustainable recourse to the commitment procedure and the safeguarding of EU antitrust enforcement altogether.

Keywords: commitment decisions, abuse of dominant position, Article 102 TFEU, enforcement policy, Alrosa, legal certainty

JEL codes: K21, L40 and L44

I. Introduction

Article 9 of Regulation 1/20031 formally introduced into EU competition legislation the possibility of settling antitrust2 cases.3 Article 9 provides inter alia, that:

Where the Commission intends to adopt a decision requiring that an infringement be brought to an end and the undertakings concerned offer commitments to meet the concerns expressed to them by the Commission in its preliminary assessment, the Commission may by decision make those commitments binding on the undertakings.

Under Article 9, the investigated company may offer forward-looking4 voluntary commitments (either behavioural or structural), in order to address the competition concerns of the European Commission (EC). If the EC deems the offer adequate, it may make the commitments binding upon the company by issuing a decision and, in turn, close the proceedings - without finding that the company has infringed Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) and without imposing a fine on it.

Arguably, commitment decisions were originally expected to be 'unusual and rare'5; and mostly meant to resolve recurring competition problems, which may, nonetheless, end up consuming significant EC resources.6 However, in recent years, the EC's use of commitment decisions suggests that this is no longer necessarily the case: the EC appears to make use of commitment decisions more and more, including in investigations that raise novel legal questions or rest upon less-established theories of harm.7 In short, commitment decisions appear to have gradually evolved from being an administrative efficiency instrument to becoming the predominant enforcement tool against (allegedly) abusive conduct by dominant companies.

The purpose of this article is to examine the gradual introduction of a commitment- based enforcement policy into EU competition law and, in particular, Article 102 TFEU proceedings. As its point of departure, the article provides an overview of the EC's decisional practice in unilateral conduct cases since the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003, and explores the reasons underlying the increasing reliance on commitment decisions. Next, the article identifies the detrimental effects that a commitment-based enforcement policy may have on the effectiveness, predictability, and decentralized enforcement of EU competition rules. Finally, the article concludes with a number of observations on the need to introduce a more comprehensive legal framework for the use of commitment decisions in Article 102 TFEU cases.

II. Commitment decisions in Article 102 TFEU cases: the EC's practice to date

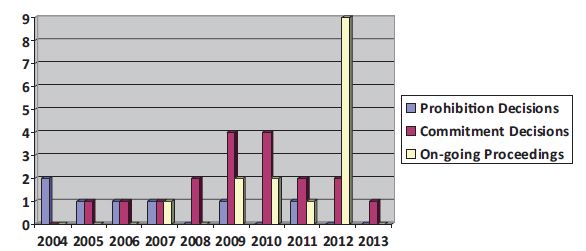

Since the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003 in March 2004, the EC has not only relied on commitment decisions to a much greater extent than it had relied on informal settlements under the previous regime8; but, furthermore, it has been increasingly relying on commitment decisions, as opposed to prohibition decisions, in order to resolve competition concerns in Article 102 TFEU cases.9 From March 2004 to date, the EC has adopted 18 commitment decisions in total,10 compared with only seven prohibition decisions against dominant companies.11 A closer examination of the EC's enforcement activity throughout the relevant period reveals that reliance on commitment decisions has been gradual:

As illustrated in the above chart, in the first five years following the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003, the EC appears to have had a rather balanced approach to enforcing Article 102 TFEU: it adopted five prohibition and five commitment decisions. In contrast, from 2009 onwards, the ratio of prohibition to commitment decisions has significantly decreased, with the EC having thus far adopted two prohibition and 13 commitment decisions.

What is more, in the universe of ongoing investigations12 probing potential infringements of Article 102 TFEU,13 there are already strong indications that some will be resolved through the adoption of commitment decisions. For example, in the ongoing investigation into Google's allegedly abusive practices in the online search market, both the company and the EC have indicated their willingness to discuss and resolve the competition concerns without engaging in adversarial proceedings.14 Google has submitted a set of draft commitments, which are currently being market tested15 and a commitment decision could be issued before the end of this year.16 In addition, according to several press reports, Samsung has apparently engaged in discussions with the EC to explore a commitment-based resolution of the investigation in Samsung/Enforcement of UMTS standards essential patents.17

The increasing use of commitment decisions as a means to resolve competition concerns arising in the context of Article 102 TFEU investigations may be due to a combination of factors, including: (i) the EC's growing confidence in the parameters of the commitment procedure; (ii) the introduction of a more effects based analysis in Article 102 TFEU investigations; (iii) the need to improve competitive conditions in certain regulated industry sectors; (iv) the preference for quick remedies that are easily implemented in fast-evolving markets; as well as, ultimately, (v) the policy orientation of the Commissioner responsible for competition policy and his cabinet. Each of these factors are analysed in the following.

The EC's growing confidence in the parameters of the commitment procedure

In the first years following the introduction of a formal commitment procedure into EU competition law, the EC was arguably uncertain about how far commitments could go. Besides the rather laconic references to commitment decisions in Regulation 1/2003, the EC had little guidance as to how this newly introduced enforcement instrument should be employed in practice.

As a result, the EC may have been minded to test the commitment procedure through a handful of selected cases, before using it more extensively in the context of Article 102 TFEU. This may have been especially so in view of the challenge by Alrosa of the commitment decision in De Beers18 in June 2006 and the subsequent ruling of the General Court of the EU (GC) in Alrosa19 in July 2007, which called into question certain aspects of the EC's practice in commitment proceedings. While this may be purely coincidental, it appears that it was not until Advocate General Kokott's opinion in Alrosa in September 2009, recommending that the Court of Justice of the EU (CoJ) overturn the GC's judgment in that case,20 that the EC made noticeably more use of commitment decisions, relative to prohibition decisions, to conclude Article 102 TFEU investigations. As demonstrated in the above chart, from 2004 until the Advocate General's opinion in September 2009, the EC had adopted only six such decisions; whereas from the issuance of the Advocate General's opinion to the end of 2009 alone, the EC went on to adopt three such decisions.21

The introduction of a more effects-based analysis in Article 102 TFEU investigations

The gradual increase in the use of commitment decisions in Article 102 TFEU cases may have also been an indirect consequence of the more effects-based economic approach towards abuse of dominance investigations, as introduced by the EC Guidance on the enforcement priorities in applying Article 102 TFEU ('Article 102 TFEU Guidance').22

Following the adoption of the Article 102 TFEU Guidance, the EC has been confronted with a heavier evidentiary and methodological burden in applying Article 102 TFEU. Specifically, abuse of dominance proceedings require the EC to develop plausible and well-articulated theories of harm that are adequately supported by economic evidence. Such evidence plays a prominent role in establishing dominance and the likely foreclosure effects of unilateral conduct.

The rise of economics in antitrust cases has arguably made it more difficult for the EC to meet the threshold for a finding of an Article 102 TFEU infringement. The EC may have, therefore, found in commitment proceedings a convenient way to circumvent the economic complexity and resource-intensive fact-gathering inherent to infringement actions.23 Where economic theory does not readily provide a solid foundation for prohibiting a certain conduct, but the empirical evidence points towards a tangible risk of harmful exclusion, it would come as no surprise that the EC uses a less burdensome instrument to limit (even on a temporary basis) the effects of potentially exclusionary practices. The EC may prefer to obtain early voluntary concessions to spending more time and effort on a case that may progressively reveal evidentiary and theoretical weaknesses, thereby depriving the EC and the market of any antitrust remedy.

The need to improve competitive conditions in certain regulated industry sectors

Another factor contributing to the more frequent use of commitment decisions over the years may be that the EC has seen in them an opportunity to supplement the liberalization process in certain regulated industry sectors. In that regard, on the one hand, commitment decisions may achieve market opening more swiftly than prohibition decisions.24 On the other hand, commitment decisions may allow ex-post antitrust intervention to achieve market outcomes that ex-ante sector regulation has been neither suited, nor designed to deliver. Perhaps the best example in support of this argument is the EC's decision making practice in the energy sector.25 Ever since the publication of the results of the 2005 sector inquiry into competition in the gas and electricity markets,26 the commitment procedure has been applied to not only bring about change in certain contested business practices27; but also, where necessary, secure structural, quasi-regulatory remedies that would otherwise not be readily accessible to the EC. For instance:

- In German Electricity Wholesale Market,28 E.ON was accused of engaging in short-term withdrawal of available generation capacity (ie limiting the supply of electricity). This practice was combined with the conclusion of long-term electricity supply contracts and the opportunity offered to new competitors to participate in E.ON power plants projects. As a result, new entrants were deterred from making investments in new generation plants. In order to resolve the EC's concerns, E.ON committed to divest approximately 5,000MW of its generation capacity.

- In German Electricity Balancing Market,29 E.ON's contested business practices included: (i) inflating balancing costs, aimed at favouring E.ON's own production affiliate; combined with (ii) preventing power producers from other EU Member States to export balancing energy into the E.ON balancing markets. In order to resolve the EC's concerns, E.ON committed to divest its transmission system business.

- In RWE Gas Foreclosure,30 RWE allegedly engaged in the following exclusionary practices: (i) the understatement of the capacity that was technically available to third parties; (ii) the non-implementation of an effective congestion management system to manage capacities on RWE's transmission network; and (iii) the setting of transmission tariffs at an artificially high level, combined with the application of additional asymmetric cost elements to RWE's competitors. In order to resolve the EC's concerns, RWE committed to divest its gas transmission network.

- Finally, in ENI,31 the business practices under examination were similar to those of RWE above. Specifically, they included: (i) the reduction of access to capacity for third parties on ENI's gas transport infrastructure; (ii) the non-implementation of an effective congestion management system; (iii) the degradation of capacity through delays in capacity allocation and uncoordinated sales on complementary pipelines; and (iv) strategic underinvestment in transport capacity enhancements. In order to resolve the EC's concerns, RWE committed to divest its shares in companies related to international gas transmission pipelines.

In essence, in all of the above-mentioned cases, the EC secured a commitment of ownership unbundling - a remedy that is included only as an option under the Third Internal Energy Market Package.32 While the imposition of ownership unbundling has faced strong political resistance in the context of energy regulation, the EC's imposition of it through commitment decisions has been less exposed to controversy: inter alia, because the companies offered it themselves.33 In contrast, it could be reasonably expected that any attempt by the EC to impose ownership unbundling through prohibition decisions would have been extensively disputed; not only politically, but also legally due to the application of a much stricter proportionality test.34

The preference for quick and easily implementable remedies in fast-evolving markets

Since infringement proceedings usually take several years to conclude, commitment decisions may be particularly suited to resolve competition concerns in fast-evolving markets (eg the IT and consumer electronics sectors), where innovation plays a critical role in the competitive process.35 Such a tendency was recently confirmed by the Vice President of the European Commission responsible for competition policy, Joaquin Almunia, in the context of the Google36 investigation, where he stated that '[. . .] fast-moving markets would particularly benefit from a quick resolution of the competition issues identified. Restoring competition swiftly to the benefit of users at an early stage is always preferable to lengthy proceedings [. . .]'.37

As illustrated by Intel, establishing an antitrust violation in dynamic and fastevolving markets may be particularly daunting and time-consuming for antitrust authorities.38 Consequently, investigations in such markets carry the risk that the remedy eventually imposed may no longer be adequate in view of the fact that the market has in the meantime 'moved on' or foreclosure has materialized. In addition, as shown by Microsoft,39 remedies imposed as part of an infringement decision may be prone to implementation problems and, ultimately, result in litigation over the defendant's precise obligations.

Furthermore, fast-evolving markets are governed by a much more dynamic competitive process. In order to maintain the lead in innovative markets, dominant undertakings have the incentive to outspend their rivals in R&D. It has been, therefore, argued that, when it comes to those markets, inadvertently prohibiting pro-competitive practices may prove to be more costly than inadvertently allowing practices that are anti-competitive.40 By 'getting it wrong' in the former instance, consumer welfare may be significantly diminished, given the ensuing potential loss of improved or newly introduced innovative products; while, in the latter instance, the anti-competitive issue may resolve itself, given the often transitory nature of market power in fast-evolving markets.41 Accordingly, if commitments are offered at an early stage in an investigation, the EC may be able to avoid two of the issues that arise when applying more traditional remedies in dynamic markets: whereas such remedies may come too late and/or go beyond what is necessary to resolve the competition problem, commitments can be both quickly applied and tailor-made.

The policy orientation of the Commissioner responsible for competition policy and his cabinet

Last but not least, the extent to which the EC relies on commitment decisions may also depend on the policy orientation of the Commissioner responsible for competition policy and his cabinet. Enforcement priorities in EU competition policy may change to a lesser or greater extent, depending on the socio-economic agenda of the Commissioner and his cabinet. For example, under the term of the Vice President of the European Commission responsible for competition policy, Joaquin Almunia,42 the EC has adopted 1 prohibition decision and 9 commitment decisions in Article 102 TFEU cases43 - with more commitment decisions apparently in the pipeline. This may be indicative of a preference on the part of Vice President Almunia for negotiated outcomes.

The question that inevitably arises is whether this surge is: (i) temporary and somewhat linked to the competition policy agenda of the Commissioner and his cabinet; or (ii) indicative of a new trend in EU antitrust enforcement, which shall persist notwithstanding changes at the top of the Directorate General for Competition and, more generally, the EC.44

Footnotes

* Yves Botteman, Partner and Head of the EU Competition Practice at Steptoe & Johnson LLP, Brussels 1050, Belgium. Email: ybotteman@steptoe.com.

Agapi Patsa, Associate at Steptoe & Johnson LLP, Brussels 1050, Belgium and PhD Candidate at KU Leuven, Belgium. Email: apatsa@steptoe.com.

1 Regulation 1/2003 on the implementation of the rules on competition laid down in Arts 81 and 82 of the Treaty, OJ L1/1, 4 January 2003. Before the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003 (also known as 'the Modernisation Regulation'), antitrust cases were settled only occasionally and informally (under ad hoc procedures) and their enforceability was questionable. See George Stephanov Georgiev, 'Contagious Efficiency: The Growing Reliance on U.S.-Style Antitrust Settlements in EU Law' (2007) 4 Utah Law Review 971-1037; and Wouter PJ Wils, 'Settlement of EU Antitrust Investigations: Commitment Decisions under Article 9 of Regulation No 1/2003' (2006) 29 World Competition 345-66.

2 The terms 'competition' and 'antitrust' are used interchangeably in this article.

3 The settlement of antitrust cases through the adoption of commitment decisions should not be confused with the settlement of cartel cases through the adoption of settlement decisions. Cartel cases may only be settled through settlement decisions (see recital 13 of Regulation 1/2003, above n 1), which - contrary to commitment decisions (see section III of this article) - establish an infringement of EU competition rules, require an admission of guilt on the defendant's part and concern past behaviour.

4 Note that the period of application of the commitments may be dependent, inter alia, on the market's

reactivity and the investments needed for certain improvements to come into effect (see the EC's Antitrust Manual of Procedures, ch 16, para 51 http://ec.europa.eu/competition/antitrust/antitrust_manproc_3_2012_en.pdf accessed 7 June 2013). Some commitment decisions (eg the EC Decision of 22 February 2006 in Case COMP/ 38381 - De Beers) do not explicitly frame their period of application. In these cases, review clauses are usually provided for. In addition, the company bound by the commitments may request the EC to re-open the proceedings, if there has been a material change in any of the facts on which the commitment decision was based (Regulation 1/2003, above n 1, art 9(2)(a)).

5 John Temple Lang, 'Commitment Decisions and Settlements with Antitrust Authorities and Private Parties under European Antitrust Law' in Barry E. Hawk (ed), International Antitrust Law and Policy (Fordham Corporate Law Institute 2005) 265-324.

6 This is borne out, inter alia, from the very brief reference made to commitment decisions in the White Paper on Modernisation of the Rules Implementing Arts 85 and 86 of the EC Treaty, European Commission, 28 April 1999, para 90.

7 A recent example of an investigation raising novel legal questions is the on-going probe into Google's allegedly abusive practices in the online search market (see Case COMP/39740 - Foundem/Google; Case COMP/39768 - Ciao/Google; and Case COMP/39775 - 1PlusV/Google). Such questions pertain, inter alia, to market definition issues, as well as the allegedly exclusionary character of certain of the company's practices. See, also, Stefano Grassani, 'The Increasing (Ab)use of Commitments in European Antitrust Law: Stockholm Syndrome', CPI Antitrust Chronicle, March 2013 (3).

8 Georgiev (n 1).

9 For the purposes of such review, the search function on the website of the Directorate-General for Competition of the EC has been used (see http://ec.europa.eu/competition/elojade/isef/index.cfm accessed 17 May 2013). The parameters employed have been: 'Commitments Decision', 'Final Commitments', 'Opening of Proceedings', 'Prohibition Decision Art. 101 & 102 Ex 81 & 82', 'Prohibition Decision Art. 102 Ex 82' and 'Proposed Commitments' as document types; having 'Art. 102 TFEU (Ex 82 EC)' as a legal basis; limited to the 'Antitrust' field; and dating from '1 March 2004' to '28 February 2013'. Note that the review has been limited to 102 Art TFEU cases and, therefore, has not taken into account prohibition or commitment decisions exclusively dealing with Art 101 TFEU infringements - even if the complaints made were based on allegations of conduct infringing both Arts 101 and 102 TFEU.

10 These are the: EC Decision of 22 June 2005 in Case COMP/39116 - Coca-Cola; EC Decision in De Beers (n 4); EC Decision of 11 October 2007 in Case COMP/37966 - Distrigaz; EC Decision of 26 November 2008 in Case COMP/39388 - German Electricity Wholesale Market; EC Decision of 26 November 2008 in Case COMP/ 39389 - German Electricity Balancing Market; EC Decision of 18 March 2009 in Case COMP/39402 - RWE Gas Foreclosure; EC Decision of 3 December 2009 in Case COMP/39316 - Gaz de France; EC Decision of 9 December 2009 in Case COMP/38636 - Rambus; EC Decision of 16 December 2009 in Case COMP/ 39530 - Microsoft (Tying); EC Decision of 17 March 2010 in Case COMP/39386 - Long-term contracts France; EC Decision of 14 April 2010 in Case COMP/39351 - Swedish Interconnectors; EC Decision of 4 May 2010 in Case COMP/39317 - E.ON Gas; EC Decision of 29 September 2010 in Case COMP/39315 - ENI; EC Decision of 15 November 2011 in Case COMP/39592 - Standard & Poor's; EC Decision of 13 December 2011 in Case COMP/39692 - IBM Maintenance Services; EC Decision of 20 December 2012 in Case COMP/39654 - Reuters Instrument Codes; and EC Decision of 20 December 2012 in Case COMP/39230 - Rio Tinto Alcan. The EC also accepted and made binding the commitments offered in Case COMP/39727 - CEZ; however the non-confidential version of the relevant EC decision had not been made public by the time this article was submitted for publication.

11 These are the: EC Decision of 24 March 2004 in Case COMP/37792 - Microsoft; EC Decision of 2 June 2004 in Case COMP/38096 - Clearstream (Clearing and Settlement); EC Decision of 15 June 2005 in Case COMP/37507 - AstraZeneca; EC Decision of 29 March 2006 in Case COMP/38113 - Prokent-Tomra; EC Decision of 4 July 2007 in Case COMP/38784 - Wanadoo Espanea v Telefonica; EC Decision of 13 May 2009 in Case COMP/37990 - Intel; and EC Decision of 22 June 2011 in Case COMP/39525 - Telekomunikacja Polska.

12 The on-going investigations are illustrated in the chart according to the year in which proceedings were initiated, namely: in 2007, in Case COMP/39294 - Microsoft (ECIS); in 2009, in Case COMP/39523 - Slovak Telekom and Case COMP/39612 - Perindopril (Servier); in 2010, in Case COMP/39226 - Lundbeck, and Foundem/ Google, Ciao/Google and 1PlusV/Google (n 7); in 2011, in Case COMP/39759 - ARA Foreclosure; and, in 2012, in Case COMP/39678 - Deutsche Bahn I, Case COMP/39731 - Deutsche Bahn II, Case COMP/39915 - Deutsche Bahn III, Case COMP/39767 - BEH Electricity, Case COMP/39840 - The MathWorks, Case COMP/39939 - Samsung /Enforcement of UMTS standards essential patents, Case COMP/39984 - OPCOM/Romanian Power Exchange, Case COMP/39985 - Motorola/Enforcement of GPRS standard essential patents and Case COMP/ 39986 - Motorola/Enforcement of ITU/ISO/IEC and IEEE standard essential patents.

13 For the purposes of the review, ongoing investigations have been taken into account based on the fact that they are being pursued either on the basis of Art 102 TFEU alone, or on the basis of both Arts 101 and 102 TFEU.

14 Foundem/Google, Ciao/Google, and 1PlusV/Google (n 7). See, for example, the speeches delivered by Joaquin Almunia, Vice President of the European Commission responsible for competition policy, on 21 May and 18 December 2012 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-12-372_en.htm accessed 17 May 2013, and http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-12-967_en.htm accessed 17 May 2013, respectively.

15 See Communication from the Commission published pursuant to Art 27(4) of Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2003 in Case AT.39740 - Google, OJ C120/22, 26 April 2013.

16 See Policy and Regulatory Report (PaRR), 27 March 2013, stating that both Google and the EC '[. . .] have established [. . .] this year is the year when this agreement should be reached [. . .]'.

17 Samsung /Enforcement of UMTS standards essential patents (n 12). However, by the time this article was submitted for publication, this had not been confirmed by either Samsung or the EC.

18 De Beers (n 4).

19 Case T-170/06, Alrosa v Commission, [2007] ECR II-2601.

20 Opinion of Advocate General Kokott in Case C-441/07 P, Commission of the European Communities v Alrosa Company Ltd, [2010] ECR I-5949. See section 'The adequacy of the EC's intervention' of this article.

21 Cf Florian Wagner-Von Papp ('Best and Even Better Practices in Commitment Procedures after Alrosa: The Dangers of Abandoning the ''Struggle for Competition Law'' ' (2012) 49 Common Market Law Review 929-70) who takes the view that the numbers should be taken with a grain of salt: according to him, the overall number of commitment decisions issued is not high enough to detect a clear trend and, in any case, time lags and the backlog of cases from the time before the entry into force of Regulation 1/2003 may also need to be taken into account.

22 Communication from the Commission - Guidance on the Commission's enforcement priorities in applying Art 82 of the EC Treaty to abusive exclusionary conduct by dominant undertakings, OJ C45/7, 24 February 2009. The adoption of the Article 102 TFEU Guidance signalled the formal (albeit already at play for a number of years) transition from the outright prohibition of certain types of conduct by dominant firms to the case-bycase evaluation of the actual or potential effects of such conduct to consumer welfare. In this context, the Art 102 TFEU Guidance clarified, inter alia, that not any competitor foreclosure is anti-competitive; but, rather, foreclosure that is likely detrimental to consumers. See, also, in that regard the DG Competition discussion paper on the application of Art 82 of the Treaty to exclusionary abuses, December 2005, http://ec.europa.eu/competi tion/antitrust/art82/ accessed 17 May 2013.

23 See, in that regard, Wagner-Von Papp (n 21) who, even though characterises the complexity of a case as a 'legitimate argument for the Commission to choose the commitment procedure' over the infringement procedure, points out the danger that the EC 'focuses, for reasons of myopia, too much on the complexity of the specific case, and discounts hyperbolically the benefit of the precedential value [. . .]' of an infringement decision.

24 See the speech delivered by Joaquin Almunia, Vice President of the European Commission responsible for competition policy, on 8 April 2011 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-11-243_en.htm accessed 17 May 2013, where he stated that '[w]e accepted the commitments offered by the companies because we were satisfied that they would grant present and future competitors more effective access to their respective markets'.

25 Out of the 18 commitment decisions adopted to date to resolve abuse of dominance concerns, 10 concern the energy sector. These are: Distrigaz; German Electricity Wholesale Market; German Electricity Balancing Market; RWE Gas Foreclosure; Gaz de France; Long-Term Electricity Contracts in France; Swedish Interconnectors; E.ON Gas; ENI; and CEZ (n 10).

26 The results of the inquiry indicated, inter alia, high levels of market concentration, vertical foreclosure, as well low levels of cross-border trade due to insufficient interconnector capacity and contractual congestion. For the complete results of the inquiry, see http://ec.europa.eu/competition/sectors/energy/inquiry/index.html accessed 17 May 2013.

27 Applicable business practices raising competition concerns in the energy sector included long-term capacity bookings, capacity hoarding, capacity degradation, strategic under-investment and customer foreclosure.

28 See n 10. The wholesale market for electricity refers to imports and generation of electricity for further resale.

29 See n 10. The balancing market for electricity refers to imports and generation of electricity for maintaining the appropriate tension level in the grid.

30 See n 10.

31 See n 10.

32 The Third Internal Market Energy Package provides three alternatives to EU Member States to ensure the separation of transmission network operations from supply and generation activities: (i) ownership unbundling; (ii) the designation of an Independent System Operator (ISO); or (iii) the designation of an Independent Transmission Operator (ITO). For more information on the Third Internal Market Energy Package, see http://ec.europa.eu/energy/gas_electricity/legislation/legislation_en.htm accessed 17 May 2013.

33 Cf the discussion on the unequal bargaining strength in Wagner-Von Papp (n 21).

34 For the different proportionality tests applicable in the context of infringement and commitment decisions, see section 'The adequacy of the EC's intervention' of this article.

35 The investigations in Rambus, Microsoft (Tying), and IBM Maintenance Services (n 10) were concluded through the adoption of commitment decisions. In addition, the EC's approach to the ongoing Foundem/ Google, Ciao/Google and 1PlusV/Google investigations (n 7) confirms the preference for commitment-based solutions in fast-evolving markets. See, also, Ivo Van Bael, Due Process in EU Competition Proceedings (Kluwer Law International 2011) 294.

36 Foundem/Google, Ciao/Google and 1PlusV/Google (n 7).

37 Speech delivered on 21 May 2012, above n 14.

38 In Case COMP/37990 - Intel, the complaint by AMD was submitted in October 2000 and the prohibition decision was adopted by the EC only in May 2009. Intel was fined on the basis that it abused its dominant position on the x86 Central Processing Unit (CPU) market by, inter alia: (i) providing rebates to computer manufacturers on the condition that they would buy (almost) all of their x86 CPUs from Intel; and (ii) making direct payments to computer manufacturers to stop or delay the launch of specific products containing other x86 CPUs and, also, to limit the sales channels for these products. The GC is currently reviewing whether to overturn the EC decision against Intel.

39 In EC Decision of 21 April 2004 in Case COMP/37792 - Microsoft, the EC found that Microsoft had abused its dominant position in the PC operating systems market by, inter alia, refusing to supply its competitors with interoperability information (IOI) and to authorize the use of that information for the development and distribution of products competing with Microsoft's own products on the work-group server operating systems market. Besides imposing a fine on Microsoft for infringing Art 102 TFEU, the EC ordered the company to supply IOI to its competitors on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms. In 2008, the EC fined Microsoft for failure to supply confidential (but not patented) IOI under reasonable royalty rates - without however determining what royalty rates would be reasonable (see, EC Decision of 27 February 2008 in Case COMP/37792 - Microsoft). The GC confirmed, in 2012, that the EC was not obliged to determine what royalty rates would have been deemed reasonable, as it is a dominant company's responsibility to determine the intrinsic value of its technology (see, T-167/08, Microsoft Corp. v European Commission, not yet published).

40 See, eg David S Evans and Richard Schmalensee, 'Some Economic Aspects of Antitrust Analysis in Dynamically Competitive Industries' in Adam B Jaffe, Joshua Lerner and Scott Stern (eds), Innovation Policy and the Economy (MIT Press 2002) 1-50.

41 Christian Ahlborn and others, 'DG Comp's Discussion Paper on Article 82: Implications of the Proposed Framework and Antitrust Rules for Dynamically Competitive Industries', 31 March 2006 http://papers.ssrn. com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=894466 target=_blank> accessed 17 May 2013.

42 Note that Mr Almunia took over the competition portfolio in February 2010, under the second Barroso Commission.

43 This finding is made on the basis of the chart provided above. For the methodology used to produce the chart, see, n 9 above.

44 For the risks inherent to commitment decisions when it comes to increased scope for political influence, see Georgiev (n 1).

To view this article in full together with its remaining footnotes please click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.