INTRODUCTION

On March 23, 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act ('Affordable Care Act')1 was officially signed into law, which included provisions that greatly altered the delivery of healthcare services in the United States. The Affordable Care Act quickly became the center of a national debate as challenges regarding the constitutionality of certain provisions surfaced.2 A key provision, which became known as the individual mandate, required citizens to either maintain 'minimum essential' health insurance coverage or pay a fine.3 This provision was at the heart of efforts to render the Affordable Care Act unconstitutional and was ultimately reviewed by the Supreme Court of the United States.4 Many believed that if the individual mandate was deemed unconstitutional, the entire Affordable Care Act would fall, thus negating the provisions entirely unrelated to the individual mandate, including provisions that related to the regulation of biologics.5 Indeed, unbeknownst to many individuals outside of the Biotechnology industry, the Affordable Care Act included the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 ('Biosimilar Act' or 'the Act').6

On June 22, 2012, the Supreme Court held that the individual mandate and provision were constitutional, thereby preserving the Healthcare Act, including the Biosimilar Act.7 This Article discusses key provisions of the Biosimilar Act, including the newly-created abbreviated approval pathway for biologics. The pathway'"s requirements, such as demonstrating biosimilarity or interchangeability, and the exclusivities granted under law will also be discussed. The proposed process and structure of the pathway will be compared and contrasted with the Hatch-Waxman Act, which addresses the abbreviated pathways for generic drugs, and the current abbreviated approval processes for biologics in Europe. Lastly, this article discusses implications for patenting biosimilar inventions and resolving patenting disputes.

I. REGULATION OF BIOLOGICS

A. General Principles

The last several decades produced great advances in the understanding of biological systems.8 This understanding led to the birth of the biotechnology industry, which provided a multitude of scientific advancements and innovations.9 Like any radical shift or advancement, however, regulations relating to these advancements required frequent, and sometimes highly-contested, government interventions.10 These interventions have come in the form of clarifying existing laws as well as forming new laws and regulations. Indeed, it was only about thirty years ago that the Supreme Court was tasked with determining whether human-made microorganisms were eligible for patent protection,11 and the term 'biotechnology' was not universally defined until about twenty years ago.12 Since its infancy, the biotechnology industry has developed an array of therapeutic and medicinal products.13 Given the less-predictable nature of biologics as compared to traditional medicines, however, the development, manufacture, and administration of biologic products to the public in a safe and effective manner have been associated with slow development phases and high treatment costs.14

The Biosimilar Act aims to balance the public policy of ensuring the availability of affordable medicinal and therapeutic biologics against the competing, but equally important, considerations of the intense investment and risk required to develop and manufacture effective and safe biologic products.15

B. Biological Substances Within the Act'"s Scope

Most biological products receive regulatory approval in the form of a biologics license application ('BLA') under section 351 of the Public Health Service Act.16 Prior to the Biosimilar Act, follow-on biosimilar products seeking regulatory approval under the Public Health Service Act were required to submit a regular approval application under section 351(a) in order to obtain licensure from the Food and Drug Administration ('FDA').17 Thus, regardless of any similarity, biosimilar applicants were required to undergo the same licensing guidelines as were required to market an entirely new and different biologic product in the United States (commonly referred to as 'innovator products') for which they were modeled after.18

Under the Act, developers of a 'biosimilar' product (or inclusive 'interchangeable' product) retain the option to request abbreviated approval by the FDA.19 Not every substance comprising biological materials is subject to the provisions of the Biosimilar Act. As indicated above, not all biologic products are licensed under the Public Health Service Act, which defines 'biologics' as:

a virus, therapeutic serum, toxin, antitoxin, vaccine, blood, blood component or derivative, allergenic product, protein (except any chemically synthesized polypeptide), or analogous product, or arsphenamine or derivative of arsphenamine (or any other trivalent organic arsenic compound), applicable to the prevention, treatment, or cure of a disease or condition of human beings.20

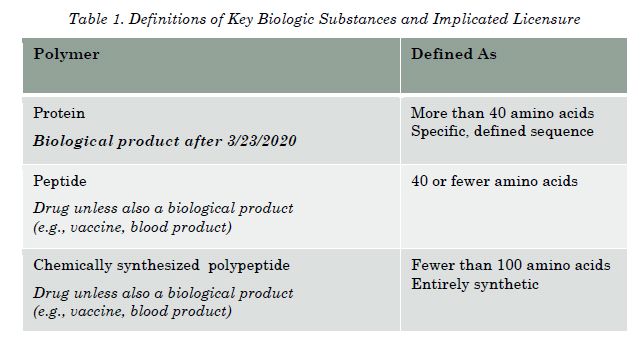

Some proteins, however, such as insulin and human growth hormones, are subject to approval under section 505 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act ('FD&C Act').21 In this regard, the Biosimilar Act is unclear exactly as to the definite boundaries of what will be deemed a 'protein,' 'peptide,' or a 'chemically-synthesized polypeptide.'22 The FDA, which is the governmental agency tasked with reviewing the biologics license applications, has provided guidance documents on the categorization of biological substances.23 These documents provide guidance as to how the FDA intends to categorize many substances, including those provided below in Table 1. Using the FDA'"s guidance, Table 1 also provides clarification of whether the product would be licensed as a biological product under the Public Health Service Act or as a drug under the FD&C Act.24

As shown in Table 1, substances categorized as proteins will be deemed 'biological products' after March 23, 2020.25 Until then, proteins (as currently defined by the FDA'"s guidance documents) will not be required to be submitted under section 351 of the Public Health Service Act, but may instead be submitted as a drug under the FD&C Act, subject to certain criteria.26 During the transition period, it generally depends if there was already another protein in the same product class that was approved as a drug (but could be used as a reference product) for the protein.

C. Abbreviated Approval Process for Follow-On Products

1. Introduction

The most significant change made by the Biosimilar Act is the creation of an abbreviated approval scheme for follow-on biologics shown to be biosimilar with an approved reference product.27 In this regard, the Biosimilar Act is the corollary to the Hatch-Waxman Act, which established abbreviated pathways for the approval of generic drug products in the United States.28 Familiarity with the Hatch-Waxman Act, however, provides little guidance with the Biosimilar Act. Many of the differences between the two Acts stem from the natural differences between biologics and traditional drugs. As one example, biologics often come from diverse living sources, and thus, there is an increased chance of transmitting diseases and agents, including bacteria and viruses.29 This lends itself to a legal framework having more validation and controls. Biologics are also more sensitive to environmental conditions; therefore, more stringent production and distribution facilities are required.30 Given the organic nature of biologics, however, most traditional sterilization techniques are not viable options.31

The abbreviated approval scheme requires the filing of a biosimilars application under an entirely new sub-section'"section 351(k)'"of the Public Health Service Act that was created through the Affordable Care Act.32 Given the creation of the new subsection, these abbreviated applications are commonly referred to as '351(k) applications,' including throughout this article.

2. Key Definitions of a Biosimilars Application '" '351(k) application'

The Affordable Care Act amended section 351 of the Public Health Services Act to include new subsection (k) which sets forth the requirements for licensing biological products as biosimilar to a reference product.33 Fortunately, the Biosimilar Act specifically addresses what constitutes biosimilarity and defines qualifying reference products.34

Each biologic product seeking expedited approval under 351(k) is compared, and ultimately judged against, a prior-approved biologic product that was licensed under the full approval process.35 This 'reference product' serves as a standard for safety, purity, and potency.36 An important issue for many biosimilar applicants is the Biosimilar Act'"s requirement that the prior-approved reference product be a 'single product.'37 Thus, the abbreviated process cannot be used for so-called combination biologics that consist of multiple biologics. Even if an applicant can successfully demonstrate that a combination biologic is merely a safe combination of two prior-approved biologic products, approval for any combination products will have to be sought through the regular approval process.

The Biosimilar Act further requires that the proposed biologic seeking expedited approval be 'biosimilar' to the reference product. As set forth in the Act:

The term 'biosimilar' or 'biosimilarity', in reference to a biological product that is the subject of an application under subsection (k), means'"

(A) that the biological product is highly similar to the reference product notwithstanding minor differences in clinically inactive components; and

(B) there are no clinically meaningful differences between the biological product and the reference product in terms of the safety, purity, and potency of the product.38

3. Demonstrating Biosimilarity

The Act further sets forth that biosimilarity is proved through (1) analytical studies that demonstrate the highly similar features, as compared to the reference product; (2) animal studies, including the assessment of toxicity, and (3) one or more clinical studies that are sufficient to demonstrate safety, purity, and potency.39

The Act was written with the correct perspective that biological products are, by nature, more variable in their properties than traditional drugs, and as such, require a more flexible framework for establishing biosimilarity. An example of this is readily shown by the third requirement, which focuses on the clinical studies for approval. This section requires 'a clinical study or studies [that include the] assessment of immunogenicity and pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics.'40 The Act further specifies that a study or studies must be 'sufficient to demonstrate safety, purity, and potency in 1 or more appropriate conditions of use for which the reference product is licensed and intended to be used and for which licensure is sought for the biological product.'41

a. FDA Draft Guidance Documents

The FDA has issued three draft guidance documents to assist applicants with the process of preparing and submitting an application for a proposed biosimilar product:

- Scientific Considerations

- Quality Considerations

- Q&A42

The FDA opened a comment phase for the draft guidance documents, which is now complete; however, to date, no final guidance documents have been issued by the FDA.43 Importantly, the FDA guidance documents may indicate that a certain product class is ineligible for approval for a license due to science and experience with the particular product class, although the guidance documents may later be modified or reversed.44

i. Step-Wise Approach

Unlike many government approval processes, including those for seeking drug approval, the FDA draft guidance document pertaining to scientific considerations advocates a 'stepwise approach' for demonstrating biosimilarity between the reference product and the biosimilar applicant.45 Thus, the FDA may, at its discretion, determine whether any of the comparisons are unnecessary and recommend presenting development plans and a milestone schedule.46 The FDA will provide feedback on a case-by-case basis.47

The FDA recommends beginning with structural and functional characterization of both products.48 Depending on the outcome of these initial studies (and later-conducted studies), applicants would likely need to provide less data for easily characterized biological products. Similarly, the FDA'"s scientific guidelines make concessions for the unknown and highly variable nature of biologics with the 'stepwise approach,' which acknowledges that many product-specific factors can influence a product development program.49 Thus, the assessment of one element may influence decisions about relevant data for the next step, and the extent of uncertainty of the biosimilarity may be evaluated to select the next steps to address that uncertainty.50 Therefore, it is believed that applicants that meet with the FDA throughout the process (such as ensuring the data conveys an understanding of the mechanism(s) of action and the safety risks of the reference product) could expedite completion of the required comparative evidence.

Footnotes

1 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, 124 Stat. 119 (2010).

2 See Health Care Reform and the Supreme Court (Affordable Care Act), N.Y. TIMES, http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/organizations/s/supreme_court/affordable_care_act/index.html (last updated Dec. 6, 2012).

3 26 U.S.C. § 5000A(b)(1) (2012).

4 Nat'"l. Fed'"n of Indep. Bus. v. Sebelius, 132 S. Ct. 2566 (2012).

5 Supreme Court Health-Care Decision: 3 Scenarios, WASH. POST. (June 21, 2012), http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/special/politics/health-care-decision/three-scenarios/index.html .

6 See Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, §§ 7001'"03, 124 Stat. 119, 804'"21 (2010) (codified as amended in scattered sections of 21 and 42 U.S.C.). The Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009 is Title VII, Subtitle A of the Affordable Care Act. Id. § 7001, 124 Stat. at 804.

7 Nat'"l. Fed'"n Of Indep. Bus., 132 S. Ct. at 2608. The Court determined that another provision of the Act was unconstitutional, however, and deemed it severable from the Act. Id. at 2607'"08.

8 NAT'"L INST. OF STANDARDS AND TECH., U.S. DEP'"T OF COMMERCE, MEASUREMENT CHALLENGES TO INNOVATION IN THE BIOSCIENCES: CRITICAL ROLES FOR NIST 1 (2009).

9 Whitney Tiedemann, First-to-File: Promoting the Goals of the United Stated Patent System as Demonstrated Through the Biotechnology Industry, 41 U.S.F. L. REV. 477, 483 (2007).

10 See, e.g., U.S. DEP'"T OF AGRIC., BIOTECHNOLOGY REGULATORY SERVICES: COORDINATED FRAMEWORK FOR THE REGULATION OF BIOTECHNOLOGY 3 (2006) (explaining the federal government'"s role in creating regulations in the beginning stages of biotechnology).

11 Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980).

12 See, e.g., U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity art. 2, June 5, 1992, 1760 U.N.T.S. 79; 31 I.L.M. 818. The United Nations and the World Health Organization each accepted the 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (Convention). The Convention defined biotechnology as 'any technological application that uses biological systems, living organisms, or derivatives thereof, to make or modify products and processes for specific use.' Id.

13 See Jean-Louis Prugnaud, Similarity of Biotechnology-Derived Medicinal Products: Specific Problems and New Regulatory Framework, 65 BRIT. J. CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY 619, 619 (2008).

14 FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., U.S. DEP'"T OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVS., CHALLENGE AND OPPORTUNITY ON THE CRITICAL PATH TO NEW MEDICAL TECHNOLOGIES, at i (2004).

15 Joanna T. Brougher & David A. Fazzolare, Will the Biosimilars Act Encourage Manufacturers to Bring Biosimilars to Market?, FOOD & DRUG POL'"Y F., Mar. 9, 2011, at 1, 5. In 2011, the average cost for a biologic therapeutic or medicinal product in the US was estimated at $16,000 annually with some costing $120,000. ANDREW F. BOURGOIN, WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE FOLLOW-ON BIOLOGIC MARKET IN THE U.S.: IMPLICATIONS, STRATEGIES, AND IMPACT 1 (2011), available at http://thomsonreuters.com/content/science/pdf/ls/newport-biologics.pdf .

16 42 U.S.C. § 262(a) (2012); see also 21 C.F.R. 601.2 (2013).

17 James V. DeGiulio, FDA Guidance Uncertainty May Deter Use of Abbreviated Biosimilar Approval Pathway, 6 LIFE SCI. L. & INDUSTRY REP. 467, 467 (2012).

18 Id.

19 Id.

20 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(1).

21 Frequently Asked Questions About Therapeutic Biological Products, U.S. FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/ucm113522.htm (last visited Feb. 12, 2013); 21 U.S.C. § 355 (2012).

22 See 42 U.S.C. § 262(i)(1) (explaining that the definition of 'biological product' includes 'protein,' but excludes 'chemically synthesized polypeptide,' and none of these terms are defined within the Act).

23 Guidance for Industry on Biosimilars: Q&As Regarding Implementation of the BPCI Act of 2009: Questions and Answers Part II, FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm271790.htm (last updated Feb. 9, 2012). The FDA has issued draft guidance documents relating to: (1) Scientific Considerations; (2) Quality Considerations; and (3) Q&A. Id.

24 Id.

25 Id.

26 See 42 U.S.C. § 355 (2012) (identifying application requirements for the safety and effectiveness 'of the drug or biological product') (emphasis added); Donna M. Gitter, Innovators and Imitators: An Analysis of Proposed Legislation Implementing an Abbreviated Pathway for Follow-On Biologics in the United States, 35 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 555, 563'"64 (2008) ('Most biologics, however, are approved for marketing under provisions of the Public Health Service Act (PHSA). Because biologics typically meet the definition of 'Üdrugs'Ü under the FDCA, they are governed by that statute as well.'). This transition period is described in the Affordable Care Act. See Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 7002(e), 124 Stat 119, 817 (2010).

27 See Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 7002, 124 Stat. 119, 804'"08 (2010) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 262(k)). The Act sets forth a heightened standard of 'interchangeable,' id., which will be described in greater detail below.

28 The Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, Pub. L. 98-417, 98 Stat. 1585 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 21 U.S.C.). The Hatch-Waxman Act is formally known as the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984.

29 See, e.g., The Basics of Biologics, ARTHRITIS TODAY, Jan.'"Feb. 2013, at 56, 57 (discussing the risks of biologics).

30 Am. Pharmacist Ass'"n, The Biosimilar Pathway: Where Will It Lead Us?, PHARMACY TODAY, Dec. 2011, at 67, 68; Gitter, supra note 26, at 564 (citing commentators'" statements: '[R]egulation [of biologics] is focused on 'Ürigid control of the manufacturing process,'" which reflects the particular scientific and historical characteristics of biopharmaceuticals'). A biologic license application must demonstrate: (1) the standards regarding safety, purity, and potency are met; (2) the manufacturing, processing, packaging, and/or holding facility meets certain standards to ensure the product'"s safety, purity, and potency are maintained; and (3) the applicant must allow FDA to inspect the aforementioned facility. Gitter, supra note 26, at 574.

31 See Daphne Allen, Sterilization: Using Radiation on EtO for Biologics, PMPNEWS.COM (May 29, 2008), http://www.pmpnews.com/article/sterilization-using-radiation-or-eto-biologics (discussing how biologics cannot generally survive the same sterilization processes which other drugs may).

32 DeGiulio, supra note 17, at 467.

33 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Pub. L. No. 111-148, § 7002, 124 Stat. 119, 804'"08 (2010) (codified as amended at 42 U.S.C. § 262(k) (2012)). Applicants must also demonstrate (1) the same mechanism of action as the reference product (if it is known), (2) demonstrate the condition(s) of use previously approved for the reference product, (3) utilize the same route of administration, dosage form, strength as reference product, and (4) ensure the proposed product must be manufactured, processed, packed, or held in a facility that meets standards for maintaining safety, purity, and potency. Id.

34 42 U.S.C. §§ 262(i)(2), (4).

35 See id. § 262(i)(3).

36 See id. § 262(i)(2)(B).

37 Id. § 262(i)(4).

38 Id. § 262(i)(2) (emphasis added).

39 42 U.S.C. § 262(k)(2)(A)(i)(I) (2012).

40 42 U.S.C. § 262(k)(2)(A)(I)(cc) (emphasis added).

41 Id.

42 Fact Sheet: Issuance of Guidances on Biosimilar Product Development, FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/ApprovalApplications/TherapeuticBiologicApplications/Biosimilars/ucm291197.htm (last updated Feb. 9, 2012).

43 Guidance for Industry on Biosimilars: Q & As Regarding Implementation of the BPCI Act of 2009, FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm259797.htm (last updated Mar. 22, 2012); FDA Issues Draft Guidance on Biosimilar Product Development, FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm291232.htm (last updated Feb. 9, 2012).

44 See FOOD & DRUG ADMIN., U.S. DEP'"T OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVS., GUIDANCE FOR INDUSTRY: SCIENTIFIC CONSIDERATIONS IN DEMONSTRATING BIOSIMILARITY TO A REFERENCE PRODUCT 1 (2012) [hereinafter SCIENTIFIC CONSIDERATIONS IN DEMONSTRATING BIOSIMILARITY].

45 Id. at 7'"8. According to the FDA, the products would be compared with regard to: structure, function, effectiveness, human pharmacokinetics (PK), human pharmacodynamics (PD), clinical safety, clinical immunogenicity, and animal toxicity. Id. at 2.

46 Id. at 4.

47 Deborah L. Lu, Draft Biosimilars Approval Guidelines Released by FDA: More Questions than Answers?, NAT'"L L. REV. (Apr. 12, 2012), http://www.natlawreview.com/article/draft-biosimilars-approval-guideline-released-fda-more-questions-answers .

48 SCIENTIFIC CONSIDERATIONS IN DEMONSTRATING BIOSIMILARITY, supra note 44, at 7. The functional characterization studies include (1) fingerprint, which is the quantification of various product attributes and (2) the extent of characterization related to the need for studies.

49 Id.

50 Id.

To view this article in full together with its remaining footnotes please click here

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.