Efficiently resolving claims can mean the difference between the survival or failure of the project or parties to the project. And, while most would agree that modern day litigation is a preferable alternative to a duel, there is no real consensus whether it's a lot or just a little better.

Some may relate to former U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren E. Burger's sentiment about litigation in the U.S.:

The entire legal profession - lawyers, judges, law professors - has become so mesmerized with the stimulation of the courtroom contest that we tend to forget that we ought to be healers of conflicts...For many claims, trials by adversarial contest must in time go the way of the ancient trial by battle and blood. Our system is too costly, too painful, too destructive, too inefficient for a truly civilized people.1

For the last several decades, Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) has been touted as the antidote to costly and destructive lawsuits. ADR can save time, energy, and money; preserve confidentiality; and achieve certainty. A sophisticated and well-run claims program can help keep a project moving even when claims arise; and, so, into many a commercial and construction contract went provisions that required all disputes to be resolved by some form of ADR.

ADR has increasingly been used in place of traditional litigation. Several organizations that offer ADR services have promoted and standardized ADR rules of engagement. The construction industry embraced ADR long ago, as the American Institute of Architects (AIA) claims to have required arbitration in its construction documents as early as 1888. However, there is a current trend in construction away from mandatory arbitration.

This article presents the basics of ADR, how ADR has fared compared to traditional litigation in recent years, as well as trends in how dispute resolution is being treated in construction contracts.

The Basics of ADR

When a dispute arises that warrants the involvement of outside legal counsel, we look to the terms of the parties' construction contract to see if and how the contract requires disputes to be resolved in a certain manner. Most contracts for large projects require some form of ADR, and may also require contractors to continue work on the project through disputes with the owner. It is critical that each party be familiar with the dispute provisions in the contract to avoid surprises when a claim arises.

At its core, ADR is largely about implementing the wisdom of Justice Burger's words, with those in the legal profession attempting to be "healers of conflicts" rather than engaging in "the ancient trial by battle and blood." It is usually better for everyone if a dispute can be resolved without some form of adversarial process.

Though many derivations exist, the most common forms of ADR (in addition to the parties talking and negotiating) are a non-binding neutral advisor, mediation, and arbitration.

With some exceptions, these forms of ADR are voluntary; that is, parties participate in ADR by virtue of the provisions in their contracts. Let's review some familiar definitions of these terms.

Non Bindiing Neutral

A non-binding neutral is someone (or three people) who is not a party to a dispute. The non-party hears the parties' respective positions; considers evidence, the parties' legal positions, and may even conduct interviews; and then advises the parties on how to best resolve the dispute.

Mediation

The American Arbitration Association (AAA) defines mediation as "a voluntary, confidential extension of the negotiation process that guides parties toward a mutually agreeable settlement, while preserving the business relationship."2

Arbitration

AAA defines arbitration as "the submission of a dispute to one or more impartial persons for a final and binding decision, known as an â€Üaward.' Awards are made in writing and are generally final and binding on the parties in the case."3

Arbitration is touted as a faster, more private, more efficient, and more final alternative to court litigation because of the procedures employed (hired judges, perhaps with expertise related to the subject matter of the dispute, and with the ability to give specialized attention to the case). This was the default in AIA contracts until the 2007 revisions.

Until recently, a common approach in dispute resolution contract provisions has been a requirement that parties first consult with a non-binding neutral, then mediate any claims on which the parties cannot agree. If they cannot reach an agreement with the assistance of a mediator, then they litigate through arbitration.

How Has ADR Fared in Recent Times?

One of the issues for anyone attempting to be a "healer of conflict" is that not all cases are suited for resolution by agreement. Sometimes the stakes are too high and one party (or both) to a dispute simply cannot afford to agree to the terms for which the other party is able to settle.

Sometimes there is an enormous benefit to one party if it drags out a dispute to either delay paying a claim or gain settlement leverage. And, more often than expected, one side is either unwilling or unable to engage in what normally would be considered reasonable behavior. In those situations, whether in traditional court litigation or ADR, costly bickering and distrust can drive up legal costs and prolong claim resolution.

In 2010, The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System (IAALS) published the results of its Civil Litigation Survey of Chief Legal Officers and General Counsel belonging to the Association of Corporate Counsel. The IAALS asked the most senior lawyers in large companies who are often involved in some form of legal disputes a number of questions about trends in litigation, including those comparing ADR and traditional court litigation.

Based on the results, the consensus was that mediation works very well for cases that are well-suited for mediation (reasonable parties that want to reach agreement), but it is unclear how much better of an alternative arbitration is than litigation.

The IAALS reported about mediation as follows:

Of respondents who reported that a percentage of their company's caseload was handled in mediation, a strong majority believe that mediation involves shorter disposition times (83%) and lower overall costs (80%) than litigation. Moreover, a majority (61%) believe that there is no difference in the fairness of the two processes.4

The IAALS reported about arbitration as follows:

Of respondents who reported that a percentage of their company's caseload was handled in arbitration, a weaker majority believe that arbitration involves shorter disposition times (63%) and lower overall costs (55%) than litigation. Moreover, a plurality (47%) believe that there is no difference in the fairness of the two processes, but a significant portion (37%) find arbitration to be less procedurally fair.5

This author does not see this as an indictment of arbitration, but instead the reality that when a dispute must be decided by a third party (as opposed to the parties to the actual dispute deciding the outcome for themselves), parties will do as much as they can and incur quite a bit of expense to ensure their cases are adequately presented.

The results of this survey are not that surprising. When all parties want a fair result without litigation, they typically can reach an agreement, even though it may take some help to get there. Mediation is well-suited for those types of cases.

For disputes where an agreement cannot be reached, and where the outcome is determined by a third party (that you must persuade to rule in your favor), the parties tend to fight pretty hard and want to make sure that their every point is heard and considered. Thus, even though arbitration is generally preferred to traditional court litigation, the competitive nature of arbitration has caused it to take on many of the attributes of traditional court litigation.

Drafting Dispute Resolution Provisions in Construction Contracts

In 2007 (three years before the release of the Civil Litigation Survey), the AIA removed the requirement that parties arbitrate from its standard form contract documents. Under the AIA forms, if the parties do not explicitly select arbitration, then the default is traditional litigation:

The revised A201 Family also eliminates mandatory arbitration, which AIA documents have required since 1888. Agreements in the revised A201 Family provide check boxes where the parties may choose arbitration, litigation, or another method of binding dispute resolution for resolving disputes.6 (emphasis added)

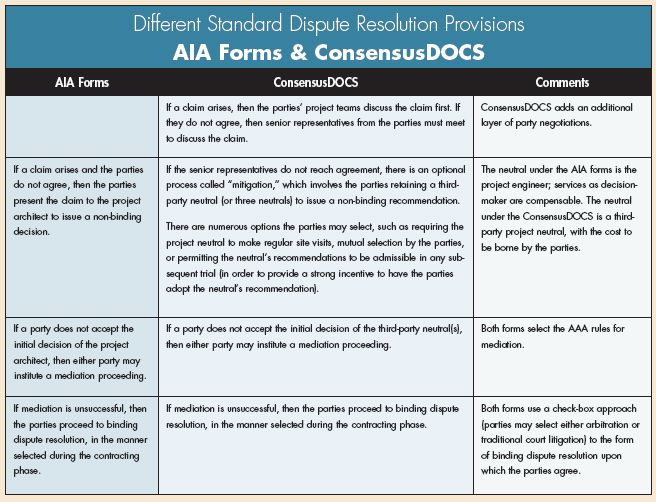

Under the AIA dispute resolution format, if a claim arises that the parties cannot agree to in the first instance, then the parties must submit their claims first to the project engineer, who provides a non-binding decision (i.e., a recommendation) as to how he or she believes the claim should be resolved.

If a party does not accept the engineer's decision, then it may initiate a mediation in accordance with the rules of the AAA. And, if that fails, then the parties proceed to an adversarial process (either litigation or arbitration, depending on which they selected during the contracting process).

At roughly the same time that the AIA released its new forms, a consortium of construction industry organizations released the Consensus DOCS - an alternative set of documents that, according to proponents, places a greater emphasis on communication and collaboration than the AIA documents.

There are meaningful differences in the dispute resolution provisions between the two forms. Under the Consensus DOCS, the parties must first attempt to resolve any claims at the project level. If unsuccessful, then senior corporate representatives are required to meet and discuss any potential claims the project teams could not resolve.

If the senior representatives are unable to reach an agreement, then the parties move to an independent neutral (optional); however, unlike under the AIA forms, the parties jointly select a project neutral. (Under the AIA forms, the project engineer acts as the neutral.)

After this "neutral" recommendation phase, Consensus DOCS also requires that the parties attempt mediation prior to a binding dispute resolution (arbitration, litigation, or some other form). Like the AIA forms, the parties decide whether to elect arbitration or litigation as part of the negotiating process.

The chart on the next page illustrates some of the differences between the dispute resolution provisions in AIA documents and Consensus DOCS.

Traditional Litigation or Arbitration?

Deciding whether to select traditional court litigation or arbitration before a dispute arises is at best an imprecise science, since each dispute involves different key players, in different financial circumstances, with different sets of project documents and e-mails, different witnesses with different availabilities, and parties with differing abilities to meet the financial cost and time investment of a substantial litigation matter.

Moreover, both the courts and those at the forefront of ADR recognize the need for continual process improvements, which may vary depending on the venue and individual legal professionals involved.

For example, the Civil Litigation Survey contains a number of suggestions to improve the arbitration process, including replacing competing expert testimony and having a single expert witness make recommendations to the arbitrators. Other changes considered relate to limiting the type and amount of information that the parties are required to ex-change in advance of a hearing on the merits. And, we will likely see some changes introduced in the future.

In the meantime, here are some key differences to help you decide on traditional court litigation or arbitration during the contracting process:

- Arbitration is private; court litigation is public. Some-times, the parties may have a strong desire for privacy; other times, the threat of a public battle encourages the parties to settle.

- Arbitration has higher up-front costs. There are substantial filing fees and the parties pay for the arbitrator's time. This means that commencing an arbitration is a "higher stakes" form of litigation. Smaller claims that can be brought up in state court may have to be foregone altogether in arbitration merely because of cost.

- Arbitration is considered to be faster than traditional court litigation and the arbitrators are typically able to provide more attention to each case. Arbitrators can often fashion procedures specific to the particular case, avoid costly procedural skirmishes, and move cases along. Thus, for larger claims, arbitration costs less in the long run.

- Arbitrators are usually subject matter experts. In court, a case is tried before a jury of peers. Therefore, the more complex the issues, the more likely there is an informed decision-maker in arbitration and less likely the parties will have an incentive to take unreasonable or unusual positions.

- Arbitration is by agreement; if all contracts do not contain consistent arbitration provisions, then it is sometimes difficult to get multiple parties into the same proceeding. If all key parties to a project cannot be persuaded to agree to an arbitration provision, then there could be logistical barriers to get all parties in a single venue if a dispute arises.

Bottom Line

Each project is different, and you can rarely know at the outset whether the parties are better-served by choosing litigation or arbitration. You can only consider the circumstances, make the best choice at the time, and then work hard to avoid litigation.

Regardless of the form or options parties to a contract select, there is a strong trend in current contract documents toward open communication, fair dealing, and substantial discussions between the parties before they engage in any form of adversarial litigation.

In that regard, the construction industry has come a long way in becoming "healers of conflicts" rather than gladiators in "the ancient trial by battle and blood."

Footnotes

1. Former U.S. Supreme Court Justice Warren E. Burger's 1984 State of the Judiciary address to the American Bar Association.

3. adr.org/aaa/faces/services/disputeresolutionservices/arbitration .

4. Civil Litigation Survey of Chief Legal Officers and General Counsel belonging to the Association of Corporate Counsel, The Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, University of Denver, 2010.

5. Ibid.

6. www.aia.org/groups/aia/documents/pdf/aias076840.pdf .

This article first appeared in CFMA Building Profits

This article is for general information and does not include full legal analysis of the matters presented. It should not be construed or relied upon as legal advice or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. The description of the results of any specific case or transaction contained herein does not mean or suggest that similar results can or could be obtained in any other matter. Each legal matter should be considered to be unique and subject to varying results. The invitation to contact the authors or attorneys in our firm is not a solicitation to provide professional services and should not be construed as a statement as to any availability to perform legal services in any jurisdiction in which such attorney is not permitted to practice.

Duane Morris LLP, a full-service law firm with more than 700 attorneys in 24 offices in the United States and internationally, offers innovative solutions to the legal and business challenges presented by today's evolving global markets. Duane Morris LLP, a full-service law firm with more than 700 attorneys in 24 offices in the United States and internationally, offers innovative solutions to the legal and business challenges presented by today's evolving global markets. The Duane Morris Institute provides training workshops for HR professionals, in-house counsel, benefits administrators and senior managers.