Introduction

There is often a tendency to assume that the Department of the Treasury's Circular No. 2301 ("Circular 230") pertains solely to preparing tax returns, tax opinions or dealing with the IRS. Further, the conventional wisdom is that a violation Circular 2302 must mean that a practitioner engaged in some sort of outrageous behavior. However, the reach of this ethical code is far greater than one might think and a violation can occur in many more situations than practitioners might otherwise expect.

In August 2011, the Department of Treasury made a number of revisions to Circular 230. A common theme of many of these changes is an increase in the breadth of the application of Circular 230. Henceforth, more practitioners will find themselves grappling with Circular 230 compliance issues.

A violation of Circular 230 is a serious matter. Practitioners who engage in sanctionable conduct may be subject to private reprimand, public censure, suspension or disbarment.3 Practitioners and their firms may also face monetary penalties.4 Historically, public discipline for violating Circular 230 usually involved obvious misconduct such as one's own failure to file tax returns or pay tax or the conviction of a criminal offense. In the future, we expect to see more cases that pertain to alleged "bad tax practice" such as a lack of due diligence, failure to give sound tax advice, conflicts of interest or other issues that indicate a tax practitioner's lack of fitness to practice before the IRS. As the reach of Circular 230 continues to grow, now is a good time to review its key provisions.

Who is Subject to Circular 230?

Circular 230 applies to those who "practice before the IRS." Practice before the IRS comprehends all matters connected with a practitioner's presentation to the IRS with respect to a taxpayer's rights, privileges or liabilities under the tax law, including:

1. preparing or filing documents, correspondence and communicating with the IRS;

2. rendering written advice with respect to an entity plan or arrangement that has a potential for tax avoidance or evasion; and

3. representing a client at IRS conferences and hearings.5

Under this broad definition of "practice" the mere preparation of a document can bring an individual within the grasp of Circular 230, regardless of whether the document is actually submitted to the IRS. For example, preparing tax planning documents generally constitutes practice before the IRS and subjects the tax planner to the duties and obligations contained in Circular 230.

Circular 230 authorizes attorneys, CPAs and enrolled agents to practice before the IRS.6 Further, enrolled actuaries, enrolled retirement plan agents, registered return preparers and selected individuals (e.g., an officer of a corporation) have limited authority to practice before the IRS.7

Any individual who is compensated for preparing or assisting with the preparation of all or substantially all of a tax return or refund claim is subject to Circular 230's duties and restrictions.8 That individual is also subject to sanction for violating the requirements of Circular 230.9

What it means to "assist in the preparation of" or what is "substantially all" of a document or return is not entirely clear. However, by expanding the application of Circular 230 to more individuals and activities, the Treasury is signaling its intent to apply Circular 230 in a broad manner. Any individual, who for compensation, assists in the preparation of any document pertaining to a taxpayer's tax liability would be wise to assume that Circular 230 could apply to that individual.

The broad grasp of Circular 230 does not stop at individual practitioners. If an individual who is subject to possible sanction under Circular 230 acts on behalf of an employer, firm or other entity, that employer, firm or entity is subject to possible sanction if it knew or reasonably should have known of the actionable conduct.10 In theory, this could lead to sanctions against not only law firms, accounting firms and return preparation firms, but any organization that employs an individual who assists in the preparation of federal tax returns or related documents.

When is Conduct Sanctionable?

Generally, a practitioner may be sanctioned if the practitioner (1) is incompetent or disreputable; (2) acting with a specific mental state or competency standard (i.e., willful, reckless or gross incompetence) fails to comply with key provisions of Circular 230; or (3) intentionally misleads a client so as to defraud that client.11

Incompetent or disreputable conduct includes a criminal conviction, evading or attempting to evade taxes, providing false or misleading information, providing a false opinion, bribing or intimidating IRS employees, misappropriating client funds, misleading potential clients about qualifications or access to special treatment, assisting or advising a client to violate tax laws, misusing tax return information and aiding or abetting another to improperly practice before the IRS.12

Sanctionable conduct also includes the loss or suspension of a professional license, willfully failing to sign a return and contemptuous conduct including using "abusive language" against IRS employees. Failure to e-file, practicing without a PTIN and representing a taxpayer without proper authorization also subjects a practitioner to sanction.13

If a practitioner subject to sanction acted on behalf of a firm or business, that firm or business is potentially subject to sanction.14 Further, practitioners with authority and responsibility for providing advice or preparing returns must implement procedures so as to ensure that all individuals in their firm comply with Circular 230. If the supervising practitioner does not implement such procedures, that practitioner is subject to possible sanction.15

The Office of Professional Responsibility (OPR) makes an initial determination of whether a practitioner has violated Circular 230. It may then propose disciplinary actions (the OPR does not actually impose a sanction; it recommends action, which the practitioner may dispute). The practitioner may consent to the proposed sanction. Or, if practitioner does not consent to the sanction, the IRS may institute a proceeding before an administrative law judge.16

Critical Rules

A brief discussion of some of the more signifi cant provisions of Circular 230 follows.

I. Failure to Obtain PTIN (§ 10.8(a))

Many tax practitioners have chafed under the requirement that they obtain a Preparer Tax Identification Number (PTIN). They note that attorneys and CPAs already have their own competency tests and licensing requirements. However, the PTIN rules are here to stay.

Any individual, who for compensation, prepares or assists in the preparation of all or substantially all of a tax return or claim for refund must have a PTIN. 17 Generally, one must be a licensed attorney, Certified Public Accountant, Enrolled Agent or Registered Return Preparer to obtain a PTIN (unless otherwise prescribed by the IRS).18

Failure to comply with Circular 230's PTIN requirements is an ethical violation that could result in sanction.19 When a practitioner provides tax advice, that advice is generally intended to assist in the preparation of a tax return. Therefore anyone who provides tax advice should consider whether obtaining a PTIN is necessary.

II. Procedures to Ensure Circular 230 Compliance (§ 10.36)

Practitioners in a position of authority must do more than ensure their own compliance with Circular 230. Supervising practitioners must ensure that all individuals they supervise comply with Circular 230 as it pertains to the preparation of returns, claims for refund or other documents submitted to the IRS.20 Further, practitioners with principal authority for overseeing a firm's practice of providing tax advice must take reasonable steps to ensure that the firm complies with the Covered Opinions, rules of Circular 230 (see below).21

A practitioner responsible for the implementation of Circular 230 compliance procedures (including compliance with the Covered Opinion rules) will be subject to disciplinary action if:

1. The practitioner, through willfulness, recklessness, or gross incompetence, does not take reasonable steps to ensure the firm has adequate procedures to comply with Circular 230, and one or more individuals who are members of, associated with, or employed by, the firm are, or have engaged in a pattern or practice, in connection with their practice with the firm, of failing to comply with Circular 230; or

2. The practitioner knows or should know that one or more individuals who are members of, associated with, or employed by, the firm are, or have, engaged in a pattern or practice, in connection with their practice with firm, that does not comply with Circular 230, and the practitioner, through willfulness, recklessness or gross incompetence fails to take prompt action to correct the noncompliance.22

Prior to August 2011, Circular 230's requirement that supervising practitioners insure that their subordinates comply with Circular 230 was limited to compliance with the Covered Opinion Rules (see discussion of Section 10.35). Circular 230 now requires supervisors to ensure compliance with Circular 230 as a whole. This provision has the potential of greatly increasing the sanctions imposed on tax practitioners who are in a position of authority and leadership.

III. The Covered Opinion Rules (§ 10.35)

One of the most discussed and controversial provisions of Circular 230 is the 2005 implementation of the Covered Opinion Rules.23 In order to limit the number of bogus tax opinions, Circular 230 imposes special duties and obligations on practitioners who issue a Covered Opinion (the "Covered Opinion Rules").24 Due to the Covered Opinion Rules' burdensome nature, most practitioners attempt to avoid the grasp of these rules by choosing not to issue a Covered Opinion. For this reason, virtually all practitioners now include at the bottom of all emails a Circular 230 legend or disclaimer which is intended to remove written tax advice from the definition of a Covered Opinion. As such, the discussion in this article is limited to "what is a Covered Opinion" as opposed to the duties one has when issuing such an opinion.

A. Definition of Covered Opinion

A Covered Opinion is written tax advice concerning one or more Federal Tax Issues that meets the definition of a Listed Transaction Opinion, Principal Purpose Opinion or four possible Significant Purposes Opinions.

1. Listed Transaction Opinion

A Listed Transaction Opinion advises on a transaction that is the same or substantially similar to a Listed Transaction.25 Transactions become listed transactions when the IRS identifi es them in published guidance as a listed transaction under Reg. §1.6011- 4(b)(2).26

2. Principal Purpose Opinion

A Principal Purpose Opinion advises on any entity, plan or arrangement with the principal purpose of avoiding or evading any federal tax.27 Unlike a Significant Purpose Reliance Opinion (discussed below), Principal Purpose Opinions are not limited to advice that pertains to a significant Federal Tax Issue. Thus, if a transaction has a "principal purpose" of avoiding tax, the Covered Opinion Rules will apply.

Any entity, investment plan or arrangement has a principal purpose of avoiding or evading tax if that purpose exceeds any other purpose. However, the transaction does not have a principal purpose of avoiding or evading tax if its purpose is to claim tax benefits in a manner consistent with the statute and Congressional purpose.28

A transaction may have a significant purpose of avoidance or evasion even though it does not have the principal purpose of avoidance or evasion.29 Straight-forward transactions such as like-kind exchanges or S-elections should not have the principal purpose of avoiding tax because their tax benef ts appear to be intended by Congress.

B. Significant Purpose Opinion

There are four Significant Purpose Opinions. These opinions advise in writing on any entity, plan or arrangement with a significant purpose of avoiding or evading any federal tax if the advice is (1) a Reliance Opinion, (2) a Marketed Opinion, (3) Opinion Subject to Conditions of Confidentiality, or (4) Opinion Subject to Contractual Protection.30

1. Reliance Opinions

A Reliance Opinion concludes at a confidence level of more likely than not (i.e., a greater than 50 percent likelihood) that one or more significant federal tax issues would be resolved in the taxpayer's favor.31 A federal tax issue is significant if the IRS has a reasonable basis for a successful challenge and the resolution of the issue could have a significant impact on the overall federal tax treatment of the matter.32 The IRS has not defined what constitutes a reasonable basis for challenge. A common rule of thumb is that a reasonable basis for successful challenge exists if the IRS has at least a 20 percent possibility of prevailing on the matter.

A practitioner can avoid issuing a Reliance Opinion by "legending out" of the definition of a Reliance Opinion. The legend or disclaimer must prominently disclose that the written advice is not intended or written by the practitioner to be used, and cannot be used by the taxpayer, for purposes of avoiding penalties that may be imposed on the taxpayer.33

2. Marketed Opinions

A practitioner issues a Marketed Opinion when the practitioner knows or has reason to know that the written tax advice will be used or referred to by a person other than the practitioner (or someone in the practitioner's firm) in promoting, marketing or recommending an entity, plan or arrangement to one or more taxpayers.34 This broad definition creates a trap for the unwary. For example, a tax opinion issued by a CPA or attorney to his or her corporate client, which will be circulated to the client's shareholders who are considering a sale or reorganization, appears to meet the definition of a Marketed Opinion.

Again, one can "legend out" of the definition of a Marketed Opinion. The legend must prominently disclose that the advice cannot be used by any taxpayer to avoid penalties, that it was written to promote the transaction or matter addressed, and taxpayers should seek independent advice based on their particular circumstances.35

3. Opinion Subject to Conditions of Confidentiality

Advice is subject to a condition of confidentiality if the practitioner imposes on the recipient of the advice a limitation on disclosure of the tax treatment or tax structure of transaction and the limitation on disclosure protects the confidentiality of the practitioner's tax strategies.36

A claim that a transaction is proprietary or exclusive is not a limitation on disclosure if the practitioner confirms in writing to all recipients of the advice that there is no limitation on the disclosure of the tax treatment or tax structure.37

4. Opinions Subject to Contractual Protection

Advice is subject to a contractual protection if the taxpayer has a right to a full or partial refund of fees paid for the advice if all or part of the intended tax consequences or benefits from the matters discussed are not sustained or the fees are contingent on the realization of the tax benefits from the advice.38

The facts and circumstances surrounding an agreement may demonstrate contractual protection even where it is not so expressly stated. These facts may include rights to reimbursements of amounts not designated as fees or arrangements to provide services without reasonable compensation.39

C. Exclusions

There are a limited number of situations where written tax advice, which would otherwise be considered a Covered Opinion, is excluded from the definition of a Covered Opinion. A Covered Opinion does not include written advice given to a client during the course of an engagement if the practitioner is reasonably expected to provide subsequent written advice that meets the definition of a Covered Opinion (e.g., the practitioner initially provides what may be referred to as a "curb side opinion").40

Further written advice that does not pertain to a Listed Transaction Opinion or a Principal Purchase Opinion is not a Covered Opinion if it is one of the following:

1. Advice concerning qualification as a Qualified Plan;

2. A State or Local Bond Opinion; or

3. Advice included in documents required to be filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

4. Advice provided to a taxpayer after a return has been filed with the IRS unless the practitioner knows or has a reason to know that the advice will be relied upon by the taxpayer to take a position on a future tax return (including an amended return).

5. Advice provided to an employer by a practitioner in that practitioner's capacity as an employee of the employer solely for purposes of determining the tax liability of the employer (e.g., "in house advice").

6. Written advice that does not resolve a federal tax issue in the taxpayer's favor unless the advice reaches a favorable conclusion at any confidence level (e.g., advice that is "Don't do this under any circumstances").41

IV. Requirements for Other Written (§ 10.37)

Even if written tax advice does not rise to the level of a Covered Opinion (e.g., "in house advice"), it must meet certain minimum standards. The advice cannot be based on unreasonable assumptions about the facts or the law or unreasonably rely on representations, statements, findings or agreements. It must consider all relevant facts and must not take into account the likelihood of audit or settlement (i.e., the advice cannot consider possible success in the audit lottery).42

A heightened standard of care is imposed where the practitioner knows or should know that the written tax advice will be used to promote, market, or recommend a course of action that has a significant purpose of avoiding or evading federal tax. The higher standard applies because of the greater risk caused by the practitioner's lack of knowledge of the recipient's particular circumstances.43

V. Best Practices (§ 10.33)

Circular 230 contains "best practices" for tax practitioners. These rules instruct practitioners to adhere to the following practices when providing advice in preparing or assisting in the preparation of a submission to the IRS:

1. Communicating clearly with one's client regarding the terms of an engagement.

2. Establishing the facts, determining which facts are relevant and evaluating the reasonableness of any assumptions or representations relating to the applicable law (including potentially applicable judicial doctrines to the relevant facts, and arriving at a conclusion supported by the law of facts).

3. Advising clients regarding the importance of the conclusions reached, including, for example, whether a taxpayer may avoid the accuracyrelated penalty if the taxpayer acts in reliance on a practitioner's advice.

4. Acting fairly and with integrity in practice before the IRS.44 Further, practitioners with responsibility for overseeing a firm's tax practice of providing advice concerning tax issues or of preparing or assisting in the preparation of submissions to the IRS must take reasonable steps to ensure that the firm's procedures are consistent with the above-mentioned best practices.45

Circular 230 specifically provides that failure to comply with the above-referenced best practices does not subject a practitioner to sanction under Circular 230.46 Thus, one might view these rules as aspirational and not mandatory. However, the best practice rules should be taken very seriously.

Failure to comply with best practice rules almost always indicates a failure to comply with some other provision of Circular 230 (e.g., lack of due diligence under Section 10.22). Further, not adhering to these rules could subject a practitioner to some additional civil liability beyond a Circular 230 sanction (e.g., failure to comply with the best practice rules might be used by a plaintiff's attorney in a malpractice case against a practitioner).

VI. Standards With Respect to Tax Returns and Other Documents (§ 10.34)

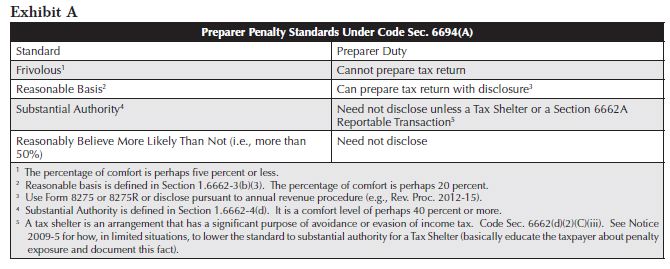

The provisions of Circular 230 "piggy back"47 on Code Sec. 6694 (see Exhibit A for a summary of the standards applicable under Code Sec. 6694). Under Circular 230 practitioners may not willfully, recklessly or through gross incompetence sign (or advise a client to take a position on) a return or claim for refund if the practitioner knows or should know that the return reports a position that lacks a reasonable basis, is an unreasonable position under Code Sec. 6694(a)(2),48 is a willful attempt to understate the tax liability or is a reckless or intentional disregard of IRS rules or regulations.49

Similarly, a practitioner may not advise a client to take a frivolous position in a document, affi davit or other paper submitted to the IRS.50 Further, a practitioner cannot advise a client to make a submission to the IRS if the submission is frivolous, intended to cause delay or intentionally disregards IRS rules or regulations.51

A practitioner must inform a client of any penalties that are reasonably likely to apply with respect to (1) a return position the practitioner provided advice on; (2) a return the practitioner prepared or signed; and (3) documents submitted to the IRS.52 The practitioner must also inform the client of the opportunity to avoid such penalties by disclosure and the requirements of adequate disclosure.53

VII. Diligence as to Accuracy (§ 10.22)

Every practitioner must exercise due diligence when practicing before the IRS. This includes exercising diligence in preparing documents relating to IRS matters and verifying the correctness of oral and written presentations made to both the IRS and one's client with regard to any matter administered by the IRS.54 A practitioner's duty to be diligent is a very broad concept. A lack of diligence would seem to exist in most instances of deficient practice-related conduct.

Further, the concept of diligence seems to require more than the mere belief that a presentation is correct at the moment it is submitted to the IRS or a client. The continued implied approval of past incorrect statements would seem to be a violation of Section 10.22. Thus, if a practitioner fails to correct an incorrect statement made to the IRS or a client, knowing full well that the recipient continues to rely on that statement. A failure to correct the error is inconsistent with the practitioner's obligation to be diligent.

A practitioner may generally rely on the work product of another so long as the practitioner uses reasonable care when obtaining the work product of the other person.55 A practitioner may also rely in good faith without verification upon information furnished by a client so long as the practitioner's reliance is reasonable.56

VIII. The Practitioner's Duty of Candor€"Prohibitions Against Providing False or Misleading Information (§ 10.51(a)(4) and (13))

Incompetent or disreputable conduct (i.e., conduct subject to sanction) includes knowingly giving false or misleading information to the IRS in connection with any matter pending or likely to be pending before the IRS.57A practitioner may also not give a false opinion, either knowingly, recklessly or through gross incompetence. Further, it is impermissible to give an opinion which is intentionally or recklessly misleading, or to engage in a pattern of providing incompetent opinions on questions of tax law.58

Accordingly, practitioners (including in-house practitioners) must take great care when advising clients on tax matters. While it is certainly permissible (indeed expected) to vigorously represent one's client, the practitioner has a duty to act with candor and integrity when addressing tax matters.

IX. Knowledge of a Client's Error or Omission (§10.21)

When a practitioner, who has been retained by a client with respect to a matter administered by the IRS, discovers a client's noncompliance with the tax law or an error or omission from any document executed under the tax laws (e.g., an incorrect prior year's tax return), the practitioner must promptly inform the client of the discovery.59 The practitioner must also advise the client of the consequences of the error, omission or noncompliance.60

Knowledge of a client's uncorrected error does not automatically require the practitioner to withdraw from the engagement. However, the broad nature of the practitioner's duty as to diligence (see Section 10.22) may, as a practical matter, require withdrawal. While the practitioner has a duty to discuss the consequences of not correcting an error on a past tax return (e.g., the consequences of not amending the fl awed return), there is no affirmative obligation on the part of the client to amend a previously filed return.61 Should the client chose not to amend, the practitioner should consider whether to terminate the representation.

X. Prompt Deposition of Matters and Responses to Requests for Information (§10.20 and 10.23)

It is not uncommon for tax practitioners who are handling a tax audit or appeal to "slow down" or delay the proceedings. While excessive delay is a questionable strategy at best, it also raises ethical issues. Delay is not permitted as a negotiation tactic or as a method to create hardship for the IRS agent.

Specifically, if the IRS makes a proper request for records or information, a practitioner must promptly respond to the request unless the practitioner reasonably has a good faith belief that the information

is privileged.62 Further, a practitioner may not unreasonably delay the prompt disposition of any matter before the IRS.63

Where the documents or information requested by the IRS are not in the possession of the practitioner or client, the practitioner must promptly provide the IRS employee seeking the information with any information the practitioner has about who has possession or control of the requested information.64 Further, the practitioner must make a reasonable inquiry of the practitioner's client about who has possession or control of the requested information.65 However, a practitioner need not make inquiry of any other persons or verify information provided by the client.66

XI. Conflicts of Interest (§ 10.29)

Another major cause of "bad tax practice" is the failure to adequately address and resolve conflicts of interest. Generally, a practitioner cannot represent a client before the IRS if the representation involves a conflict of interest.67

A conflict of interest exists if (1) the representation of one client will be directly adverse to another client; or (2) there is a significant risk that the representation of one or more clients will be materially limited by the practitioner's responsibilities to another client, a former client or third person or by the personal interest of the practitioner.68

Where a conflict exists, a practitioner may still handle the matter if the practitioner reasonably believes that the practitioner will be able to provide competent and diligent representation to each affected client, the representation will not otherwise violate the law and each affected client waives the conflict in an informed consent at the time the conflict is discovered by the practitioner. The client must provide a written consent waiving the conflict within 30 days of giving verbal consent.69 The written waiver must be retained for at least three years after the conclusion of the representation of any affected client.70

A common conflict, which is often overlooked, occurs when a practitioner prepares a tax return, either as a signing or nonsigning preparer, and then handles the subsequent tax audit or appeal. In this situation there may be a conflict if the practitioner has a personal interest that conflicts with the client's interest. For example, if the IRS asserts an Accuracy Related Penalty, will the practitioner be hesitant to argue that the penalty should not apply because of the taxpayer's good faith reliance on the practitioner's tax advice?

Another common conflict exists when the practitioner represents both a husband and wife and the two spouse's interests become adverse. In such a situation, the practitioner may be unable to represent either spouse.

In all situations it is important that the practitioner identify a possible conflict of interest, consider if the conflict is waivable and, if so, obtain a timely written waiver from the client(s).

XII. Conclusion

As the breadth of Circular 230 has increased, it has become far more important that tax practitioners understand the requirements of this ethical code. Circular 230 prohibits conduct that many would not characterize as extreme or outrageous behavior. Rather, Circular 230 contains a broad set of rules designed to ensure "quality tax practice." Failure to comply with these rules can lead to significant adverse consequences. It is critical that all practitioners understand the requirements of Circular 230. If a practitioner is not clear about his or her ethical obligations, that practitioner should seek assistance.

Footnotes

1 Circular 230 is authorized by Title 31 U.S.C.§330. It is contained in 31 C.F.R. Subtitle A, Part 10 (Rev. 8-2001) (see "www. irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/pcir230.pdf" ).

2 Unless otherwise noted, section citations are to Circular 230 (Rev. 8-2011).

3 Circular 230, Subpart D; §10.50.

4 §10.50(c).

5 §10.2(a)(4).

6 §10.3.

7 §10.3(d), (e) and (f); § 10.7.

8 §10.8(a) and (c).

9 Id.

10 §10.50(c)(1)(ii).

11 §10.50(a); § 10.52.

12 §10.51.

13 Id.

14 §10.50(c)(1)(ii).

15 §10.36.

16 §10.50(d); § 10.60.

17 §10.8(a).

18 Id.

19 §10.51(a)(17).

20 §10.36(b).

21 §10.36(a).

22 §10.36(a)(1) and (2); §10.36(b)(1) and (2).

23 T.D. 9165 (2004), effective June 20, 2005.

24 §10.35.

25 §10.35(b)( 2)(i)(A).

26 Id.

27 §10.35(b)( 2)(i)(B).

28 §10.35(b)( 2)(i)(B)(10).

29 Id.

30 §10.35(b)(2)(i)(C).

31 §10.35(b)(4). The audit lottery cannot be considered when giving a verbal advice. See Discussion of Section 10.34.

32 §10.35(b)(3).

33 §10.35(b)(4)(ii).

34 §10.35(b)(5).

35 §10.35(b)(5)(ii)(A - C).

36 §10.35(b)(6).

37 Id.

38 §10.35(b)(7).

39 Id.

40 §10.35(b)(2)(ii)(A).

41 §10.35(b)(2)(ii)(B-E).

42 §10.37. The rule for "Other Written Advice" seems to be, for all practical purposes, a less formal version of the Section 10.35 Covered Opinion Rules.

43 Id.

44 §10.33(a)(1-4).

45 §10.33(b).

46 §10.50; 10.52(a)(1).

47 The Circular 230 standard is not exactly the same as Code Sec. 6694(a). The former requires the OPR to show willful, reckless or grossly incompetent conduct; while under the latter, a penalty could apply if the return preparer merely lacked a Reasonable Basis for a position.

48 An unreasonable position under Code Sec. 6694(a)(2) is generally a position which there is no Substantial Authority (see Reg. §1.6662-4(d)) for the position. When determining whether the Substantial Authority standard is met, the likelihood that a return will be audited is not to be considered (e.g., the "audit lottery" is not to be considered). Reg. § 1.6662-4(d)(2).

49 §10.34(a).

50 § 10.34(b).

51 Id.

52 §10.34(c)(1)(ii).

53 §10.34(c)(2)(c)(ii). As such, it seems imperative that tax practitioners have a solid working knowledge of the Code Sec. 6662 accuracy related penalty and how to avoid that penalty.

54 §10.22(a).

55 §10.22(b).

56 §10.22(b), referring §10.34.

57 §10.51(a)(4).

58 §10.51(a)(13).

59 §10.21.

60 Id.

61 E. Badaracco, SCt, 84-1 ustc ¶9150, 464 US 386, 393.

62 §10.20(a)(1).

63 §10.23.

64 §10.20(a)(2).

65 Id. This Rule is troubling in that it is likely that if a practitioner makes inquiry of his or her client, the client communications to the practitioner may well be privileged under the attorney client privilege or the Code Sec. 7525 tax practitioner privilege. If the practitioner reasonably believes in good faith that such information is privileged, it would seem that the appropriate response is to raise the privilege issue with the IRS (citing Circular 230 §10.20(a)(1)) and see if the IRS wants to challenge the privilege claim by enforcing a summons under Code Sec. 7602. However, Section 10.20(a)(2) does not explicitly state that the practitioner is excused from disclosing client communications because they are privileged. Further, it is not clear that the right not to produce privileged material under Section 10.20(a) (1) would apply to the client statements the practitioner is obligated to request under Section 10.20(a)(2).

66 §10.20(a)(2).

67 §10.29.

68 §10.29(a)(1) and (2).

69 §10.29(b).

70 §10.29(c).

Previously published in Journal of Tax Practice & Procedure

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.