Introduction

This recession has been one of the most deeply penetrating; it has affected organizations across the board, including not-for-profits. The number of financially distressed companies has grown, as have the resulting implications for their boards of directors. This is especially true for companies that are approaching the zone of insolvency, the legal term applied when a company is in imminent danger of going bankrupt.

As illustrated in Exhibit 1, courts have found that the fiduciary responsibility of directors and officers at companies approaching or residing in the zone of insolvency is not to the corporation and its shareholders, but to a wider community of stakeholders, particularly creditors. For this reason, boards must face the possibility that creditors will bring derivative claims against directors for breach of fiduciary duty. Recent court rulings have clarified that only during insolvency do creditors have standing to bring derivative claims against directors for breach of fiduciary duty. However, defining the actual zone of insolvency, including how and when a company has entered it and what new obligations are triggered by it, remains elusive.

Grant Thornton LLP's Corporate Advisory & Restructuring Services practice recently conducted a study of financial and nonfinancial indicators to investigate how distress trends have changed. The results were conflicting, leaving the situation hard to discern.

Unfortunately, in trying times, directors and officers must act based on the evidence available. Recognizing that doing so may inhibit their ability to make fully informed decisions, Grant Thornton has developed a framework that identifies practical guidelines and considerations for board members.

How have distress trends changed?

Financial measures of insolvency: Inconclusive at best, misleading at worst

Directors and officers who are concerned about their responsibility in insolvency face the same problem the courts face: The zone of insolvency does not necessarily begin at a fixed point in time. Often it is only visible in the rearview mirror. The path to insolvency should be thought of as a spectrum with a somewhat defined upper boundary — insolvency — with numerous gradations leading toward it.

Two tests for insolvency have been established:

- Balance sheet test — Under the balance sheet test, a company is insolvent if its liabilities are greater than its assets at fair value.

- Equitable test (or cash flow test) — Under the equitable test, a company is insolvent if it cannot meet maturing obligations as they become due in the ordinary course of business.

Grant Thornton applied the above tests to approximately 3,600 public companies for the time period 2005 to 2009 to understand how the recession has affected the solvency of companies. Ordinarily, the tests would involve a detailed valuation and cash flow analysis to arrive at the fair values of the assets and ability to meet upcoming liabilities. However, in order to run these tests on a broader data set of companies across a range of industries, the following two financial ratios served as proxies:

- Total assets/total liabilities (TA/TL) as a proxy for the balance sheet test

- Cash flow from operations/current liabilities (CFO/CL) as a proxy for the equitable test

We also used the Altman Z-score, a widely accepted indicator of insolvency, to double-check the results of the proxy tests.

The results of this analysis are presented in Exhibit 2. Based on the proxies for the two insolvency tests, there was lower distress across these companies in 2009 compared with 2007:

- Median TA/TL at the end of 2007 was 1.93, compared with 1.89 at the end of 2009, indicating that, at a broader level, the health of company balance sheets was near pre-recession levels.

- Median CFO/CL increased from 0.38 in 2007 to 0.44 in 2009, suggesting that some companies had more resources available to meet their current obligations.

For the same data set and the same time frame, the Altman Z-score indicates — albeit counterintuitively — that the percentage of distressed companies at the end of 2009 was higher than at the end of 2007:

- Percentage of companies with an Altman Z-score of less than 2.7 — This percentage was higher in 2009 than in 2007. The median Altman Z-score in 2009 was also lower than the median Altman Z-score in 2007. The Altman Z-score results suggest that by the end of 2009, more companies either faced bankruptcy in the subsequent two-year period (Altman Z-scores of between 1.8 and 2.7) or experienced extreme financial distress (Altman Z-scores of less than 1.8).

To sum up: As a measure of the comparative health of companies over the recessionary period from December 2007 to the end of December 2009, financial indicators alone are inconclusive as indicators of distress. Thus, nonfinancial indicators must also be taken into consideration.

Altman Z-score: This is a predictive model created by Edward Altman in the 1960s. This model combines five different financial ratios to determine the likelihood of bankruptcy amongst companies. The Altman Z-score is calculated as Z = 1.2*X1 + 1.4*X2 + 3.3*X3 + 0.6*X4 + 1.0*X5, where

X1 = Working Capital/Total Assets

X2 = Retained Earnings/Total Assets

X3 = EBITDA/Total Assets

X4 = Market Value of Equity/Total Liabilities

X5 = Net Sales/Total Assets

Nonfinancial indicators: Distress is on the rise

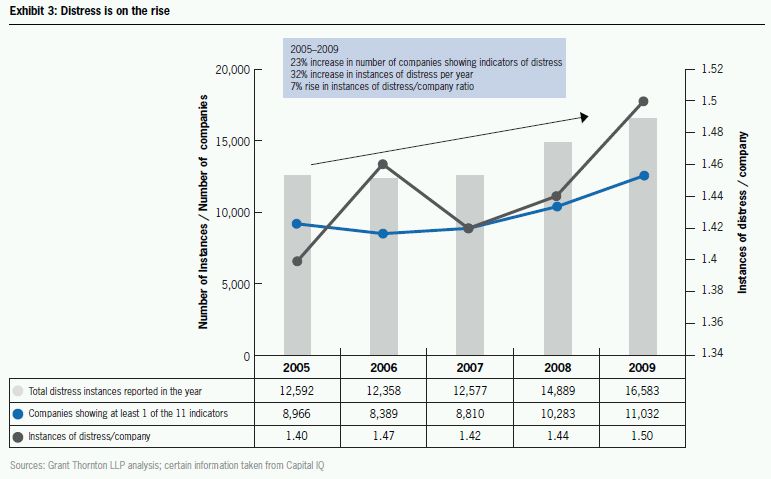

Grant Thornton analyzed publicly available information for the period 2005 through 2009 for nonfinancial indicators of distress. Such indicators, which are often precursors to insolvency and/or a bankruptcy filing, include the following:

- Lawsuits and other legal issues

- Discontinued operations

- Impairments/write-offs

- Delistings from stock exchanges

- Debt defaults

- Seeking finance partners

- Going concern opinion issued by the independent auditor

- Delayed SEC filings

- Sales of noncore and core assets and businesses

- Business reorganization

- SEC inquiries

- Material weaknesses

- Internal control issues

Our analysis of publicly available information revealed a 23 percent increase between 2005 and 2009 in the number of companies exhibiting one or more nonfinancial indicators of distress. During that period, the number of instances grew by more than 32 percent, and the average number of instances per company rose from 1.4 to 1.5, an increase of more than seven percent.

Delving deeper, we analyzed the effects of the recession on the key nonfinancial distress indicators shown in Exhibit 4. The following trends emerged:

- Litigation and disputes increased by 17 percent. This is hardly surprising, given the economic upheaval and resulting wave of business bankruptcies over the past two years. Litigation has been and will continue to be one of the favored methods of recovery for failing companies as they seek financial redress from fraud and resolve other disputes.

- Discontinued operations and downsizing were up by more than 80 percent as a direct result of cost cutting. Decisions associated with the sale of assets — both core and noncore — generally have a high impact on considerations involving the zone of insolvency, along with a high potential for litigation.

- Premiums paid for past acquisitions were written off by many companies. Whether because of overpayment or because of failure to derive integration synergies, such impairments and other asset write-offs are symptomatic of underlying problems that have the potential to bring companies closer to the zone of insolvency.

- Increasing numbers of debt defaults and delistings from stock exchanges further indicate a market still in flux.

In summary, our analysis of nonfinancial indicators, as opposed to financial ones, shows a clear trend of increasing distress. Such conflicting results necessitate new approaches by boards of directors.

Decision framework for directors and officers

Traditionally, directors and officers have relied on the business judgment rule when making decisions. This rule calls for them to have a rational business purpose behind each decision made. But this recession has redefined the meaning of the word rational. Leaders and organizations are dealing with a historic amount of distress and deciding on numerous issues simultaneously. More and more directors are finding themselves forced to take severe measures that would have been considered irrational under the old paradigm. The zone of insolvency is particularly challenging for directors and officers because of the potential repercussions of past decisions that favored one stakeholder group over another.

As illustrated in Exhibit 5, the decision framework for directors and officers has three essential components as seen from bottom to top:

- Decisions and scenarios that may involve the zone of insolvency (bottom) — It is imperative that directors and officers understand potentially risky decisions and situations that may be scrutinized in the years to come. A sample set is provided as guidance; however, only the facts of an individual case will determine what other decisions may come under scrutiny.

- The level of distress and the mindset of directors and officers (vertical axes) — As the company's actual or perceived distress grows, board members must transition from a passive mindset regarding oversight to one that is more active and hands-on.

- Consideration categories (top and center) — Six primary categories were identified based on our experience with companies spanning a multitude of industries and in various stages of financial and operational health. The first five categories relate to internal matters, while the sixth relates to the external environment. These categories, which are discussed in more detail later in the paper, include common actions and considerations for a company to keep in mind based on its level of distress.

Operations: Move from a monitoring role to being actively engaged in the business

In times of financial distress, the day-to-day activities of directors and officers will change markedly. Those who needed to review only certain management and financial reports during good times will find themselves reviewing budget-to-actual variances regularly when the company is distressed. Since liquidity is key to survival during a downturn, directors and officers will be called upon to implement tough measures to conserve cash and cut costs in the short term. We would, however, caution companies to think strategically and focus on the long term when making such decisions, whether they involve reducing the workforce or slashing capital expenditures. A recent Grant Thornton article on commercial real estate1 illustrates how companies that invest during a recession have an advantage when that recession ends.

For a distressed public company, it is especially critical to maintain compliance with listing agencies (e.g., the NYSE) and the SEC. By failing to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley Sections 404 and 302 and other regulatory requirements, or by failing to maintain and monitor adequate internal controls, a distressed public company can exacerbate its situation.

Legal: Find an indispensable and trusted adviser

Legal and regulatory considerations change dramatically in times of financial distress. Therefore, it is imperative that directors and officers have legal advisers who understand the bankruptcy code. Following are related legal and regulatory issues your advisers should be aware of:

- Insolvency laws vary from country to country and will affect businesses in the United States that have foreign operations.

- Changes to industry regulations such as accounting rules may have a significant impact on the financial statements and hence on bank covenants.

- Bankruptcy rules regarding fraudulent conveyance and preferential treatment, along with rules relevant to operating in the zone of insolvency, will be important to know. Drastic steps such as the sale of assets or the discontinuance of operations may involve many legal nuances.

- D&O insurance should be able to cover any personal liabilities arising from lawsuits.

Fraud: Realize that the likelihood of fraud increases in times of financial distress

The prevalence of fraud, both internal and transactional, increases in times of distress. Once stakeholders see signs of distress – decreases in stock values, disappearing bonuses, inability to meet payroll, overstretched payables and inadequate cash flow — loyalty can evaporate. Fraud can range from stolen intellectual property to shrinkage in inventory. These conditions can persist as companies emerge from distress and may derail a recovery. Directors and officers should assess the anti-fraud controls in place and develop corrective action plans. Finally, all transactions contemplated during the period should require thorough due diligence, often from an independent third-party adviser.

Complexity: Understand the issues; it's too risky not to

As a company approaches the insolvency zone, the board's decisions may be subject to review. In the current economic climate, the risk is too high for officers and directors not to fully understand complex issues. Understanding the implications of decisions is equally important. Directors should maintain an ongoing dialogue with management regarding the complexities facing the company and their potential impact on future operations. It cannot be stressed enough that all scenarios should be modeled into the company's projections and that all assumptions should be tested against on-the-ground realities. Be certain that all of the what-if questions are asked and all of the downside scenarios are modeled, along with off-balance sheet obligations, contingent liabilities, debt covenants and 13-week rolling cash flows. Understand the liquidity implications arising from budgeting scenarios. Closely and frequently monitor the company's performance against its projections so that if things change quickly, contingency plans can be put in place.

Keeping fraud risk in mind

The conditions that lead to increased fraud risk for distressed companies can persist, even after the worst of the distress is over. Without fraud risk remaining a top concern, a company's recovery can be derailed.

In a recent Grant Thornton white paper,2 our Advisory Services professionals discussed the key issues organizations face when it comes to identifying, dealing with and protecting themselves from fraud:

- Businesses are readying themselves for renewed growth. Many are hoping to take advantage of opportunities that arise from the flow of federal stimulus money. Others are looking for a chance to snap up struggling companies or distressed assets.

- With internal audit departments stretched thin in the wake of repeated downsizing, some companies may find their fraud prevention controls to be less than optimal.

- Companies desperate to escape bankruptcy may be tempted to hide less attractive aspects of their financial profiles from eager buyers. Consequently, buyers that skimp on due diligence can easily be burned.

All of these factors make today's business environment especially conducive to fraud. Directors and officers of distressed or formerly distressed companies need to remain vigilant.

Documentation: Protect your blind side

The importance of maintaining comprehensive documentation, including meeting minutes and processes leading up to decisions, cannot be overstated. In time-critical situations, decisions are made based on limited information. Hindsight is always 20/20 and decisions considered appropriate at the time can be debated and torn apart in the future. Of course, delaying decisions or inaction on any issue can also be contested in the future, especially if the company becomes insolvent or files for bankruptcy.

External: Maintain integrity in your communications

It is critical to be connected to external stakeholders during times of financial distress. Develop a framework for evaluating suppliers and understanding their financial condition, since disruption in the supply chain can harm your business. Interacting with your key customers to understand issues and risks to top-line assumptions is crucial in maintaining the viability of company projections. Keep tabs on your competitors; recessions can drive companies to attempt desperate measures such as slashing prices, which can be harmful to other companies and the industry as a whole. Engage with lenders frequently and keep them abreast of the company's financial position. And finally, consider whether you need to hire an independent third-party public relations firm.

Conclusion

Although the shades of gray in the zone of insolvency are especially difficult to discern given today's mixed economic signals regarding the recovery, it is critical that directors and officers monitor both financial and nonfinancial distress indicators to determine the positions of their companies. Decisions can be approached in an informed, structured manner by using Grant Thornton's decision framework. Thorough documentation — to include advice received from legal counsel, financial advisers and any other third-party advisers — will provide an additional measure of confidence.

Depending on the amount of distress their companies are facing, directors and officers will need to adopt a more active, hands-on mindset regarding oversight. They must be cognizant of the interests of the stakeholders to whom they are responsible. The ever-closer scrutiny of bankruptcy-related matters by shareholders and the courts is unquestionably part of today's market climate. Our structured approach to decision-making and our compliance advisory services can help directors and officers verify that each tough call is guided by the best possible process as their companies navigate around and within the zone of insolvency.

Footnotes

1 Why a rising tide won't lift all boats, www.GrantThornton.com/CREarticle .

2 CorporateGovernor white paper, Spring 2010: Fraud in the economic recovery, www.GrantThornton.com/FraudandRecovery .

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.