Contents

Preface

Chapter 1

What Is a Patent?

Chapter 2

What Is Potentially Patentable?

Chapter 3

What Is Not Patentable?

Chapter 4

How Is a Patent Obtained?

Chapter 5

What Should You Do Before Filing a Patent

Application?

Chapter 6

What Shouldn't You Do Before Filing a Patent

Application?

Chapter 7

How Are Foreign Patents Obtained?

Chapter 8

Who Is an Inventor on a Patent?

Chapter 9

Who Owns the Patent?

Chapter 10

How Long Is a Patent in Effect?

Patent Group

About Foley Hoag

Beth E. Arnold

Preface

Patenting generally offers a superior means for legally protecting most inventions, particularly since:

- copyright, when available, does not provide a broad scope of protection; and

- the ability to effectively protect an invention as a trade secret is in constant jeopardy, due to publication or oral disclosure.

Unfortunately, the patenting process can be complicated, time-intensive and costly. However, costs can often be minimized and opportunities for establishing value in products and technology maximized if scientists and business professionals with an understanding of the patenting process are actively involved throughout.

This publication was prepared to provide an overview of patenting, particularly as it pertains to innovative technologies such as biotechnology and information technology.

Chapter 1

What Is a Patent?

A patent is a government-issued document that provides its owner with rights to prevent competitors from profiting from the invention defined by the patent claims, for the duration of the patent term. In the U.S., any of three different kinds of patents may be applied for, depending on the nature of the subject matter to be protected:

1) The most popular utility patent protects a variety of products and processes, and is the focus of this publication.

2) The design patent protects any new, original, or ornamental design.

3) The plant patent is useful only for protecting new and distinctive asexually reproduced plant varieties. (Sexually reproduced varieties are also entitled to certain legal protection upon certification, pursuant to the Plant Variety Protection Act of 1970.)

The rights conferred by a patent can be enforced in court by the patent owner against competitor infringers to protect or increase the patent owner's market share. For example, the patent owner can seek an injunction against and/or damages from any party infringing a valid claim of the patent. Alternatively, all or some of the rights can be contracted to a commercial partner (via an assignment or license agreement). A patent is an intangible asset and, depending on what it covers, can be very valuable.

The Origin of Patents and Trademarks

Intellectual property protection originated in medieval Europe. Members of medieval guilds would share their knowledge with each other but guard it from disclosure to outsiders. Their closely guarded techniques and skills are precursors of today's trade secrets.

Partly in response to the closed societies arising from the guilds, governments passed laws to encourage dissemination of inventions and ideas by granting exclusive rights – a patent or copyright – for a limited period of time to anyone who disclosed a new and useful item, process, or creative work into the public domain.

The early guilds also used symbols and pictures to identify services performed or products made by guild members. Those guild symbols are the precursors of today's trademarks.

What a Patent Is Not

It is important to realize that a patent does not give its owner an affirmative right to make, use, or sell the invention defined by the patent claims. Instead, it confers the right to prevent others from making, using, or selling – or even offering to sell – the invention within the United States or importing it into the United States, unless the owner's permission is obtained. This is a subtle but important distinction.

Blocking Patents

Because even a patented product may infringe another's patent, it is advisable to conduct a freedom to operate search to detect potential blocking patents prior to putting a new product on the market, implementing a new manufacturing process, or offering a new service. Each component of a product or process, as well as the process used to make a product and methods for using a product, should be searched separately, either manually (by searching the stacks of issued patents in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) and/or in an appropriate computer database.

Blocking patents are particularly prevalent in burgeoning technology fields in which pioneering patents of broad scope that claim basic enabling technologies are frequently granted.

If a potential blocking patent is identified, a patent attorney should be retained to construe the patent claims and determine if any claim may be infringed.

If a blocking patent is identified early, it may be possible for a potential infringer to design around ( i.e., develop an alternative product or process that is not covered by the patent claim). Alternatively, early identification of a blocking patent may facilitate the negotiation of more favorable licensing terms than could be obtained when the product or process is actually being sold.

Do You Need a Non-Infringement Opinion?

You should retain a patent attorney to review the patent and, if appropriate, prepare a written non-infringement opinion if:

- a product made, used, or sold by your company;

- a process used by your company to make a product;

- a service offered by your company; or

- a business method practiced by your company potentially infringes a patent issued in a country in which the product is being made, used, offered for sale, or sold; or where a process, service or business method is being used, offered for sale, or sold

Invalidity Challenges

If the blocking patent is not available for licensing or is only available under unreasonable terms, the patent's validity may be challenged in court or in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Although an issued U.S. patent is presumed to be valid, the law recognizes that improperly examined patents may occasionally issue. Accordingly, a potential infringer can retain a patent attorney to challenge the validity of a patent by:

- initiating a reexamination proceeding in the USPTO; or

- instituting a declaratory judgment action in an appropriate federal district court.

Chapter 2

What Is Potentially Patentable?

The definition of what constitutes potentially patentable subject matter in the U.S. is defined in Section 101 of Title 35 of the United States Code:

Whoever invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof, may obtain a patent therefor, subject to the conditions and requirements of this title. (35 U.S.C. 101)

In the landmark 1980 Supreme Court case, Diamond v. Chakrabarty, claims to a genetically engineered bacterium that contains energy-generating plasmids were held to be patentable subject matter. In support of its holding, the Supreme Court interpreted 35 U.S.C. 101 to "cover everything under the sun made by man." This decision established broad parameters for patenting biotechnology in the U.S. and paved the way for the establishment of an industry.

Likewise, in the information technology arena, recent decisions have held that software and computer programs that perform a specified function, including financial calculations, may be patentable subject matter.

Product claims protect a composition, manufacture, or machine regardless of how it was made or the use that is made of it. Therefore, generally speaking, issued product claims provide optimal protection. However, process claims – including processes for making or using a product or affecting a certain result – can also provide useful protection:

- if claims on the product cannot be obtained;

- if only product claims of narrow scope are obtainable; or

- as an extra layer of protection, even if broad product claims are obtainable.

In addition, 35 U.S.C. Section 271(g) makes unauthorized importation, sale, or use of a product made abroad by a process patented in the U.S. (a process of making claim) an infringing activity, as long as that product has not been materially changed by a subsequent process or does not become a trivial and nonessential component of another product.

Process of using claims can be particularly useful for protecting new therapeutic uses for a known compound.

The greater the number and types of patent claims protecting a product or process, the greater the chance that a potential infringer will be deterred or that an infringement suit by the patent owner will be successful.

Chapter 3

What Is Not Patentable?

Under U.S. law, a patent will not be granted on an invention if it does not overcome four hurdles defined in three separate sections of the U.S. patent statute (35 U.S.C. 100 et seq.). These same basic hurdles (i.e., patentability requirements) exist under the laws of most foreign countries, with slight variations.

The Hurdles Ahead

Is your invention:

1) Statutory (or appropriate) subject matter?

2) Useful?

3) New?

4) Nonobvious?

Hurdle #1: Patentable Subject Matter

Section 101 of the patent statute requires that an invention correspond to one of the specified classes of patentable subject matter: i.e., that it is a process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter (see Chapter 2).

Hurdle #2: Utility

This second hurdle to patentability, the utility requirement, is easily met by most inventions. For example, games are considered useful. However, tied in with the utility requirement is the requirement that an invention actually work. The lack of utility is the reason why patent offices typically reject attempts to try to patent perpetual motion machines. Use of a nucleic acid sequence as a nonspecific probe is not enough. To be patentable, the law requires that the patent application provide "a specific and substantial utility that is credible" for all that is claimed. Throw away utilities like the use of a nucleic acid sequence as a "probe" will not be enough.

Hurdle #3: Novelty

The invention must also be new. A product of nature (something that occurs in nature and is substantially unaltered by human hands, i.e., has not been isolated or purified) will be rejected as unpatentable under 35 U.S.C. 101 for not being "new." Similarly, a method that is nothing more than a mathematical algorithm is not considered to be new.

In addition to the requirements of section 101, much of 35 U.S.C. 102 is devoted to defining what is not new or novel (in the statute's terminology).

First to Invent

The U.S. patent system is unique in the world in recognizing rights in an invention as of when it was created. The U.S., therefore, has a first-to-invent patent system. In contrast, countries that have a first-to-file patent system judge potential rights only as of a patent application's filing date, regardless of who may have been the first to invent.

In the event that two pending patent applications, or a patent application and an issued patent, claim the same or similar subject matter, the USPTO may initiate an interference proceeding to determine the actual first inventor. Alternatively, one of the patent applicants may take steps to provide an interference. Generally, the first to conceive of (think of) an invention and actually reduce (that invention) to practice (by making the product or performing the process) or constructively reduce the invention to practice (by filing a patent application disclosing the invention) will be awarded priority status (i.e., is the "Senior Party") in an interference.

Prior Art

Despite the fact that in the U.S. a patent is awarded to the first to invent, it is nevertheless advisable to diligently file a patent application to predate the occurrence of prior art events that could place the invention in the public domain.

Inventions that are publicly known are not truly new (novel) and therefore will not be awarded patent protection. The following examples of prior art can preclude a patent from being awarded:

- description of the invention in a printed publication (including a journal article, abstract, published patent application, issued patent, or publicly available thesis or grant application) authored either by the inventor(s) or someone else and appearing anywhere in the world (35 U.S.C. 102(a), 102(b));

- public knowledge (e.g., an oral disclosure) or use (e.g., a demonstration) of the invention by the inventor(s) or someone else in the U.S. (35 U.S.C. 102 (a), 102(b));

- sale of the invention or even an offer for sale by the inventor(s) or someone else in the U.S. more than one year before the patent application has been filed (35 U.S.C. 102(b)); or

- description of the invention in a U.S. patent by another with a filing date prior to the date of invention by the applicant or in a published U.S. or international patent application by another filed in the U.S. before the invention by the patent applicant (102(e)).

Inventors can also lose the right to obtain a patent if there is evidence that the invention:

- has been abandoned (35 U.S.C. 102(c));

- was invented by someone other than those named on the patent application (35 U.S.C. 102(f)); or

- was first made by someone else anywhere in the world, provided the prior development has not been abandoned, suppressed, or concealed (35 U.S.C. 102(g)).*

Although section 102 provides a one-year grace period following the occurrence of certain prior art events, (the 102(b) events), during which a U.S. patent application may still be filed, patent rights may be lost in certain foreign countries. For example, there is no grace period for obtaining a European patent, and the Japanese and Australian systems offer only a six-month grace period for obtaining a patent (see Chapter 7 for more details).

Who Will Win the Interference?

Interference A:

Inventor 1, the first to conceive of the invention and reduce it to practice, wins.

Interference B:

Inventor 1 will win as long as diligence in reduction to practice prior to Inventor 2's reduction to practice can be shown - otherwise, Inventor 2 wins.

Hurdle #4: Nonobviousness

The final hurdle to patentability is the nonobviousness requirement:

A patent may not be obtained though the invention is not identically disclosed or described...if the difference between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the subject matter pertains...(35 U.S.C. 103(a)).

The invention must be an unobvious advance over the prior art. Determination that an invention is not obvious is typically based on four factual inquiries:

1) Scope and content of the prior art at the time of the invention

2) Differences between the prior art and the claimed invention

3) Level of skill in the art to which the invention pertains

4) Evidence of secondary considerations, such as a long-felt need, commercial success, failure of others, and unexpected results.

Chapter 4

How Is a Patent Obtained?

To be granted a patent on an invention, a patent application must be prepared, filed, and prosecuted in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Because of the many legal and technical requirements, a patent application is generally best drafted by a patent attorney (a scientist or engineer who is registered to practice before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) and the courts of at least one state) or a patent agent (a scientist or engineer who is registered to practice before the USPTO but is not a member of a state bar).

Provisional Patent Application

Since June 8, 1995 – the day the U.S. implemented the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) – the USPTO has accepted provisional patent applications (patent applications containing a disclosure of the invention, but not necessarily claims). As long as a comparable, complete patent application (including claims) is filed within one year after the provisional patent application's filing date, the date on which the provisional application was filed serves as the priority date for determining patentability, with the official patent application filing date used to calculate the patent term. As a result, the publication, public use, or sale of the invention occurring after the filing date of the provisional application but before the filing date of the complete application will not be considered prior art for determining the novelty and/or non obviousness of the invention (see Chapter 3).

Utility Patent Application

When a utility (as opposed to a provisional) patent application is filed in the USPTO, a PTO official briefly reviews it for content and, if acceptable, grants a filing date and directs the application to the appropriate examining group. Depending on the backlog of applications in the group, it may take anywhere from a few months to a few years for an application to be examined after it is filed.

Accelerated Examination

On August 25, 2006, the USPTO introduced a program that will provide patent applicants with a final decision regarding patentability within 12 months after filing the patent application. To qualify, applicants must electronically file a complete application with an appropriate petition, fee, and Accelerated Examination Support Document. In addition, the application must contain no more than 20 total claims and three or fewer independent claims, which must be directed to a single invention. The applicant must also make a statement that a pre-examination search was conducted on all claimed elements, given their broadest reasonable interpretation and including non-patent literature.

Restriction Requirement

A patent examiner initially looks at the claims to determine whether they are directed to two or more independent and distinct inventions. For example, a patent application for a new recombinant protein may include claims to any or all of the following:

- the protein itself;

- antibodies to the protein;

- nucleic acid sequences encoding the protein;

- nucleic acid sequences antisense to the coding sequence;

- processes for making the protein;

- therapeutic uses of the protein;

- diagnostic uses of the antibodies; and

- diagnostic use of the antisense nucleic acids.

The patent examiner may consider each of these eight elements to be independent and distinct inventions, in which case the examiner may issue a restriction requirement.

The patent applicant is typically given one month in which to elect one invention (i.e., one of the groupings of claims) for further examination on the merits or to dispute the restriction. If the restriction stands, nonelected claims will remain pending and may be pursued separately by filing a divisional patent application any time before the elected claims issue as a patent. The GATT-implemented change in patent term – from 17 years after issuance to 20 years after the original patent application filing date (see Chapter 10) – provides incentive for filing divisional applications on commercially important claims sooner rather than later.

Although restriction of a patent application inevitably results in increased effort and expense for obtaining the issuance of various claims, the restriction is a USPTO acknowledgment that each group of claims is separately patentable. A subsequent ruling of invalidity on claims directed to one invention, therefore, would not necessarily invalidate restricted claims directed to another invention.

Following restriction, or if no restriction is required, the patent examiner conducts a search of the prior art and substantively "examines" the patent application to determine whether the invention:

- is directed to appropriate subject matter (35 U.S.C. 101);

- has at least one utility (35 U.S.C. 101);

- is novel (35 U.S.C. 101 and 102); and

- was not obvious at the time it was made (35 U.S.C. 103).

Examination of a Patent Application to Determine Whether It Appropriately Enables, Describes, and Claims the Invention

The examiner studies the patent application itself to determine whether the invention has been adequately described and enabled (35 U.S.C. 112). The body of the patent application (the specification), must contain a written description of the invention and of the manner and process of making and using it...to enable one of ordinary skill in the art to which it pertains...to make and use the same (35 U.S.C. 112).

Enablement

The enablement requirement is at the root of all patent systems. In exchange for teaching the public how to practice an invention, the inventor is provided exclusive rights to prevent others from exploiting the same invention for a limited term. The scope of enablement must be commensurate with the breadth of the claims. In other words, broad claims must be broadly enabled.

Biotechnology Claims: To enable an invention involving certain biological materials such as rare isolates, hybridomas, or gene-containing cell lines, particularly where further characterization of the material can not be provided, that material must be deposited in a recognized culture depository, such as the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) located in Manassas, Virginia. For U.S. patent purposes, a deposit need not be made until patent claims involving the material are otherwise indicated as allowable by the USPTO.

In contrast, most foreign patent offices require that deposits be made prior to the foreign patent application filing date, potentially resulting in delayed patent filings (until after a deposit can be made) and unnecessary deposits (when it is uncertain whether a written description of how a particular material was obtained adequately enables). Many foreign patent offices, including the European Patent Office (EPO), also require that organisms deposited to support a patent application be made available upon request to any person as of the patent application publication date (i.e., 18 months from the priority filing date). Unless the patent applicant selects the expert option, this requirement can jeopardize the ability to protect the material as a trade secret, if claims of appropriate scope do not ultimately issue as a patent. It could also provide a potential competitor with a ready source of the material.

Information Technology Claims: To enable an invention involving computer software, the overall functionality of the software must be disclosed so that a programmer with ordinary skill could create the program without undue experimentation. The level of detail required thus depends on the level of complexity of the software.

For example, a simple program involving routine function calls to various pieces of software and to hardware components could be appropriately enabled by providing a flow chart and functionally describing how the program works. A much more complicated program – for example, a computer operating system – may require a considerable amount of detail to be disclosed, perhaps even requiring the source code itself to be appended to the application.

Written Description

Only that which has been specifically described by sufficient and relevant identifying characteristics (as opposed to just functionally) in the patent specification may be claimed. The specification, therefore, should describe all possible parameters and components of an invention, preferably in very specific as well as in more general terms.

For an invention disclosing a nucleic acid or protein to be adequately described, the specification must include a sequence listing for any disclosed (not merely claimed) protein (or peptide) consisting of four or more amino acids, and any disclosed nucleic acid of ten or more nucleotides. In addition to appearing in the written patent application, sequences must also be submitted to the USPTO on computer disk.

Best Mode

In addition to appropriately describing and enabling the invention, the patent specification must disclose the best mode known by the inventor(s) for carrying out the invention at the time the patent application was filed. This requirement prevents inventors from retaining critical elements of the invention as trade secrets.

Claims

The claims are the most important part of an issued patent: They define the scope of protection on the disclosed invention. 35 U.S.C. 112 requires that the patent specification conclude with one or more claims specifically pointing out and distinctly claiming the invention.

Clearly, the patent applicant should devote a great deal of thought to the claims when drafting and prosecuting an application.

Words and terms used in the claims that are not generally known or that may have a specific or different meaning in relation to the invention must be defined in the patent specification. One of the challenges of drafting a patent application is to provide language that is both specific and of a broad enough scope to provide useful protection. Another challenge, particularly in biotechnology, is in disclosing and claiming commercial embodiments (the ultimate products or processes to be marketed). A good patent attorney not only describes what the inventor discloses, but looks ten years into the future and describes everything that may be developed.

Claims in a patent application are not typically allowed upon initial examination. Almost inevitably, the examiner issues an office action rejecting the claims and/or objecting to the specification on one or more grounds. The patent applicant can then respond by pointing out errors in the examiner's reasoning and/or amending the claims or specification. Although a patent applicant may introduce evidence (such as declarations or affidavits) to support arguments, no new matter may be added to the patent application during prosecution.

On the other hand, additional information or data developed after a patent application was filed that broadens the scope of the original claims may be filed in the U.S. via a Continuation-In-Part (CIP) application, which is based on the original, parent application. In determining patentability in light of prior art disclosures, any claim in a CIP that is supported by the parent patent application will be entitled to the parent's filing date, while claims supported only by the new disclosure will only be entitled to the CIP's filing date for priority purposes. The GATT-implemented change in patent term from 17 years after issuance to 20 years after the original patent application filing date (see Chapter 10) places a premium on filing well-considered patent applications at the outset, rather than relying on CIP practice.

Information Disclosure Statement

Each individual associated with filing and prosecuting a patent application has a duty to act with candor and good faith. In other words, patent attorneys/agents and inventors are obliged to disclose all prior art relevant to the patentability of an invention that is known before the patent application is filed or that becomes known during prosecution. This obligation is fulfilled with the filing of an Information Disclosure Statement (IDS) listing relevant prior art. Relevant prior art not known at the time an initial IDS is filed can be supplied later in a Supplemental IDS.

A violation of the duty of candor and good faith can be raised by an accused infringer as an affirmative defense to render the patent permanently unenforceable based on inequitable conduct. In any case, a patent is stronger if all relevant prior art was cited during prosecution, since the patent is presumed to be novel and nonobvious over the prior art cited during prosecution.

If all the above requirements of the patent application are met and the patentability hurdles surpassed, a patent will issue on allowed claims.

To be eligible for the provisional or official patent application's filing date for priority purposes, divisional or continuation patent applications (e.g., for pursuing nonelected claims, or claims broader than the allowed claims), must be filed before the allowed claims issue as a patent. It is generally a good idea to keep a patent application pending in case the issued patent does not include claims that are later determined to be desirable.

Chapter 5

What Should You Do Before Filing a Patent Application?

Before filing a patent application, you should document the invention, determine whether patenting is appropriate, and determine whether the invention is patentable.

Documenting the Invention

As discussed in Chapter 3, the U.S. patent system is unique in providing patent rights to the first true inventor, rather than to the first to file a patent application. As a result, evidence of when, how and by whom an invention is made can become critical in an interference proceeding for determining who is entitled to U.S. patent rights. In addition, appropriate notebook records documenting the conception of an invention can be important for obtaining a patent by swearing behind – and thereby removing – prior art that predates the patent application's filing date, but which occurred after the invention was made.

Scientists typically record experimental protocols and results in a notebook. For patent purposes, the notebook should also contain written records of conception (mental realization) of inventions and, if possible, actual reduction to practice (successful completion of the invention). Patent applications may, however, be based solely on conception, in which case the filing of a patent application (or provisional application, if one is initially filed) constitutes a constructive reduction to practice.

To serve as adequate evidence, details related to the conception of an invention should be documented by the inventor and each page corroborated on that date by the inventor and at least one – and preferably two – credible people who:

- are not inventors;

- have "witnessed and understood" the invention; and

- have been obligated in writing to keep the invention confidential

Determining Whether Patenting Is Appropriate

After an invention has been documented, a decision can be made as to whether patent protection should be pursued. This determination often involves business, scientific, and patent law considerations.

A patent should only be pursued if the invention has sufficient commercial potential to merit the costs and effort involved. Although the commercial potential may be difficult to assess at the outset, factors to consider include:

- size of the potential market

- whether noninfringing alternatives are available

- ease and cost of production and use

- whether there is a recognized need for the invention

- expected useful life of the product

- whether trade secret protection is preferable

Trade Secret Protection

Pharmaceutical companies traditionally protected fermentation technologies for producing antibiotics as trade secrets rather than by patent. This strategy was effective because the antibiotics themselves provided no indication of how they were made, and obtaining sufficiently broad process claims that effectively prevent a competitor from designing around can be difficult.

Similarly, software companies often guarded as a trade secret the basic algorithm supporting a computer program.

However, if trade secret (as opposed to patent) protection is to be pursued, appropriate safeguards must be in place so that the invention will in fact be classified as a trade secret by a court. To ensure trade secret status, access to laboratory or manufacturing facilities containing trade secrets should be limited to "authorized personnel only," and the few employees knowing the trade secret should be contractually obliged to keep the information or materials confidential. For example, if a computer algorithm is to be protected as a trade secret, it should not be registered for copyright.

Although, the deposit requirement for a computer software program is satisfied if the first and last 25 pages of the source code are deposited. Unlike a computer algorithm, it is possible to keep a significant portion of a computer software program confidential while still registering the code for copyright protection. The trick is to make sure that the essence of the program is not within the first or last 25 pages of code (which are filed with the copyright registration).

Statutory Invention Registration

Another (defensive) option is to obtain a Statutory Invention Registration (SIR) from the USPTO. Although an SIR cannot be enforced against an infringer, it in effect creates prior art, which prevents subsequent inventors from obtaining a patent on the same invention. The same effect, however, can be accomplished by publishing or otherwise publicly disclosing the invention.

Determining Whether The Invention Is Patentable

In addition to assessing commercial potential, the patentability of an invention should be assessed before a patent application is filed. As discussed in Chapter 3, an invention is patentable if it:

- is directed to appropriate subject matter;

- has at least one utility;

- is novel; and

- was not obvious when it was made.

Novelty is a critical issue. An invention is not novel if either before it was created by the inventor(s) or more than one year before a patent application was filed, the invention was:

- described in a printed publication in the U.S. or a foreign country;

- publicly known or used by others in the U.S.;

- on sale or even offered for sale in the U.S.; or

- described in a U.S.-filed patent application that issued as a patent.

Inventors generally know if they or a colleague had published or given a talk on subject matter related to the invention. In addition, a patentability search can be carried out to identify prior art of which the inventors may not be aware.

Any publication appearing to disclose a complete or partial invention should be obtained and reviewed before a patent application is drafted. If the reference provides an enabling description of the complete invention as described in a claim, that invention will be unpatentable in most foreign countries. In the U.S., however, the invention may still be patented if a patent application is filed on or before the one-year anniversary date of the printed publication. If the publication is authored by someone other than the inventor(s), the inventor(s) must swear (and preferably prove) that he or she conceived of the invention before the publication date of the printed publication (or, if the publication is an issued U.S. patent, prior to the patent application filing date).

If a reference describes only part of an invention, as described in a patent application, the reference may still bear on the obviousness of the claimed invention. Even if an invention with high commercial potential is arguably obvious in view of prior art references, secondary considerations such as a patent application may nevertheless be filed, since an obviousness rejection can be rebutted by evidence of commercial success, or long-felt need.

Chapter 6

What Shouldn't You Do Before Filing a Patent Application?

Any action by an inventor that could prevent issuance of a patent should not occur before a patent application (provisional or original) has been filed. In other words, prior art should not be created by an inventor.

Specifically, before a patent application has been filed on an invention, the inventor(s) should not:

- submit a document disclosing the invention for publication or funding approval (e.g., a grant proposal);*

- talk about the invention to others;

- demonstrate the invention;

- offer the invention for sale (advertise); or

- sell the invention.

* Note, however, that the barring event is publication or public disclosure, not submission.

Chapter 7

How Are Foreign Patents Obtained?

Patents are generally applied for and granted on a country-by-country basis. Fortunately, however, foreign filing decisions need not be made at the outset. Pursuant to the Paris Convention, which has been signed by virtually every industrialized country, a foreign patent application corresponding to a U.S. application may be filed any time within one year after the U.S. patent application filing date and still retain the U.S. application's filing date for priority purposes.

This means that a foreign patent application will be treated as if it were filed on the same day as the U.S. application for purposes of determining patentability, so that any publication, public use, or sale of the invention occurring after the filing of the U.S. application is not considered prior art with respect to the foreign patent application.

Any public disclosure occurring before the U.S. patent application filing date, however, is considered prior art in the foreign patent application. Like the U.S., Canada provides a one-year grace period in which to file a patent application after the occurrence of certain prior art events (see Chapter 3). Japan, Australia, and many other foreign countries provide a six-month grace period. It is important to recognize that European countries require absolute novelty and do not provide for a grace period for filing a patent application after the occurrence of a public disclosure.

It is generally advisable to wait until close to the one-year anniversary of the U.S. filing date to file a corresponding foreign patent application to ensure that the foreign application is as complete as possible. This is particularly important for inventions in which substantial developments can occur within the course of a year.

Direct National or Regional Foreign Filings

Although most foreign patents are obtained by filing a patent application with the patent office of each country in which protection is desired, several regional filing systems issue a single patent that is enforceable in any member country. For example, a patent issued from the European Patent Office (EPO) in Munich, Germany, can be enforced in European Patent Convention (EPC) member counties (i.e., most European countries); two regional filing systems provide protection in certain African regions (OAPIand ARIPO); and the Eurasian Regional system provides protection in certain countries of the former Soviet Union.

The major advantage of pursuing a regional patent is that only one application (in English, for an EPO application) and one foreign associate (a patent attorney registered to practice before the relevant patent office) need be involved. Upon grant, the regional patent can be made effective in whichever of the designated countries protection is still desired by meeting national formal requirements and paying national processing fees.

Although filing a single regional application is obviously simpler than filing separate applications with each individual country's patent office, this approach can also be more risky, since only one examiner will rule on the patentability for all member countries. This risk can be minimized, at a price, by filing national patent applications at the same time the regional application is filed.

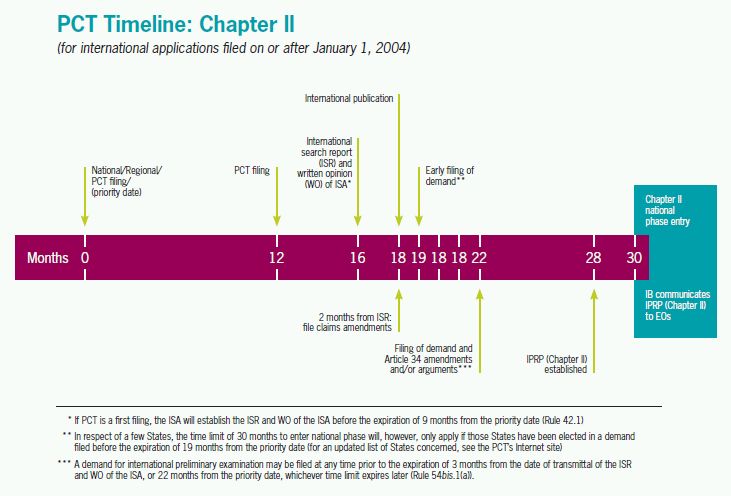

Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) Foreign Filings

Since many inventions require substantial research and development prior to commercialization, a popular option is to file an application under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) rather than a direct national or regional patent application.

The PCT route is a convenient way to obtain a patentability search (in Europe or in the U.S.) and an initial examination on a single, international patent application. By filing a PCT application, examination costs for each country or region (including obtaining and filing appropriate translations) can be delayed for eight months (if Chapter I is selected) or 18 months (if Chapter II is selected). In addition to the advantage of deferred expenses, the results of the examination and the passage of time can enable a better assessment of the patentability – or marketability – of the invention.

Although it delays the payment of major expenses and provides for a single search, foreign filing via the PCT can increase the overall cost of patenting since the costs of initial examination are in addition to – not in lieu of – the patent costs in each designated country or region.

Filing internationally via the PCT also ultimately delays the granting of a foreign patent and, therefore, the rights to exclude others. Therefore, if a competing product or process is already being made, used, or sold in a foreign country, direct national filings should be pursued.

Patentability Requirements of Foreign Countries

Although patentability requirements in most foreign countries are similar to those in the U.S., some differences should be considered when filing a patent application outside of the U.S. For example, some countries will not allow patents for software or for certain biotechnology-related inventions such as transgenic animals. In addition, methods for the treatment of human or animal body by surgery, therapy, or diagnostic methods practiced on the human or animal body cannot be patented in Europe.

Patent protection for therapeutic or diagnostic methods can often be obtained in Europe simply by drafting claims in different formats known as the first medical use or second medical use (if a first medical use is already known). First or second medical use claims will not be enforced against the medical practitioner, but rather against the company supplying the practitioner with the therapeutic or diagnostic product.

Chapter 8

Who Is an Inventor on a Patent?

Inventorship is a legal question that can be complex and is therefore best determined by a patent attorney. Unlike authorship, not all members of a research team are necessarily inventors. The only members qualifying as inventors are those who made a material contribution to the conception of the complete and operative invention as defined in the patent claims. As long as the conception is of a workable invention, the ultimate reduction to practice is irrelevant to an inventorship determination.

If the reduction to practice requires extraordinary skill, however, or if no way of making or using a conceived composition of matter is known, contributions to the reduction to practice may be inventive contributions. In certain unpredictable sciences, U.S. courts have held that a complete conception can only occur when the invention has been successfully reduced to practice.

A good faith determination of inventorship must be made by a patent attorney before an application is filed. Although inventorship can be corrected on a pending application or patent, procedures for correcting inventorship are time consuming and, therefore, costly. In addition, if material misrepresentations or omissions were made to the Patent Office regarding inventorship, inventorship can not be corrected and the patent will be held invalid. Inventorship must be determined for each claim of the patent application. For there to be joint or co-inventors of a claim, each inventor must have made some contribution to the same subject matter. According to the patent statute, however, each joint inventor need not physically work together or at the same time [or] ...make the same type or amount of contribution (35 U.S.C. 116).

A patent may be held unenforceable if the inventorship determination is erroneous and was made with "deceptive intent."

Chapter 9

Who Owns the Patent?

Inventorship provides the starting point for determining who owns the patent. The general rule is that the inventors own the rights in the invention, including the rights to apply for and obtain a patent. When there is more than one inventor, U.S. patent law provides that:

In the absence of any agreement to the contrary, each of the joint owners of a patent may make, use, offer to sell or sell the patented invention within the United States, or import the patented invention into the United States without the consent of and without accounting to the other owners (35 U.S.C. 262).

The rule that an inventor owns the patent rights in his or her invention is, however, subject to two general exceptions. An inventor may not own the patent rights if the rights have been expressly or impliedly obligated to another. An inventor owns the rights in his or her invention, unless those rights have been expressly or impliedly obligated to another.

Asigned employment agreement can expressly obligate an inventor to assign the rights in the invention to an employer. Most courts will enforce an employment agreement that requires assignment to the employer of all rights to inventions conceived and reduced to practice by the employee during and in connection with his or her employment. Courts in the majority – but not all – states will also enforce employment agreements that obligate assignment to the employer of inventions conceived by the employee during the course of employment, even if reduced to practice some time later – for example while the employee is working for another employer.

Holdover Agreement

A hold over agreement, which requires an employee to assign to the employer rights to inventions that were conceived only after the employee left the company, is generally only enforced by a court if it is reasonable, based on the totality of the circumstances. Factors weighed in determining reasonableness include whether the restriction is:

- necessary to protect a legitimate interest of the employer (for example, the employer's trade secrets or confidential information, or if the invention is an improvement to an invention originally conceived during employment);

- not unduly restrictive on the employee's employment opportunities; and

- not injurious to the public's interest in promoting competition, creativity, and invention.

Implied Contract

Even when a written employment agreement has not been signed, a court may nevertheless recognize an implied contract, or obligation on the employee to assign patent rights to his or her employer. For example, when the employee was specifically hired to invent or solve a particular problem, an implied contract to assign between the employee and employer may be held to exist. In addition, where the employee holds a position of trust with the company (such as a corporate officer), a court may read an implied contract to assign patent rights to that company.

Shop Right

Although there may be no express or implied obligation to assign patent rights to the employer, in certain circumstances courts may recognize a shop right in the employer. According to the shop right doctrine, if an employee uses a nontrivial amount of the employer's time and/or resources to create an invention, the employee must grant to the employer a nonexclusive, nontransferable, royalty-free license to use the invention for the term of the patent.

Assignment Agreement

Although ownership rights may be expressly or impliedly obligated to an employer, title in the invention will remain with the employee until an assignment agreement has been signed by the inventor/employee (preferably in the presence of a notary, but at a minimum in the presence of two credible witnesses). Because employees can change jobs and the right to sue for infringement rests only with the patent title holder as of the time the infringement occurs, it is in the employer's best interest to have employee/inventors sign assignment agreements and file those signed documents with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) in conjunction with the filing of a patent application. Although not a requirement, proper recordation of a patent in the USPTO effectively:

- lists the patent assignee on the cover page of the issued patent; and

- protects the owner against challenges by successive purported assignees should the inventor later attempt to reassign the same patent to a new entity – for example, a new employer.

Assignment information recorded after a patent has issued may be obtained from the USPTO by filing a request and paying a fee.

An assignment typically transfers all personal property rights provided by a patent, or an undivided fraction of all of the rights (that is, a 50% interest). Transfer of lesser rights in a patent may be accomplished through a license agreement.

Chapter 10

How Long Is a Patent in Effect?

Historically, U.S. utility and plant patents were granted for a period of 17 years, measured from the patent issue date (indicated on the cover page of the patent). Design patents, on the other hand, were granted for a period of 14 years from the date of issuance.

Pursuant to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), however, which became effective in the U.S. on June 8, 1995, the term of a U.S. patent issued on an application filed after June 7, 1995, is 20 years from the earliest effective U.S. filing date.*

Transitional status was granted to patents in force on June 8, 1995 and to patents that issue from applications filed prior to June 8, 1995, by providing a term of either 17 years from the issue date or 20 years from the earliest effective U.S. filing date (the longer of the two). The term of a design patent was unaffected by GATT and continues to be 14 years from the date of issuance.

Extensions and Patent Term Adjustments (PTAs)

The GATTlegislation provides for a maximal five-year extension of the 20-year term, if certain delays were involved with obtaining the patent. For example, extensions in term would be available if the patent application was involved in an interference or was appealed, or if prosecution was suspended at some point due to government issuance of a secrecy order.

* i.e., The filing date of the patent application or the earliest filing date of a prior U.S. application to which a continuation (e.g., file wrapper continuation, continuation, continuation-in-part, or divisional) patent application claims priority.

For applications filed on or after May 29, 2000, the patent term extends 20 years from the effective filing date together with any patent term adjustment (PTA) that may be afforded under the new rules. For example, the patent term may be extended for the PTO's failure to take action within prescribed limits or otherwise issue the patent within three years. While the patent term itself cannot be reduced, any extension which may be warranted in view of PTO failures may be lost if the PTO determines that the applicant failed to engage in reasonable efforts to conclude processing or examination of an application. Examples resulting in such a finding include an applicant failing to reply within three months after receiving an office action, or an applicant submitting an incomplete reply etc.

In addition, pursuant to the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984, patent life may be extended a maximum of five years to compensate for delays in commercialization due to a regulatory (FDA or EPA) approval process.

Maintenance Fees

Issued patents will expire unless maintenance fees are paid at designated time periods. If the patent owner can prove within two years of the expiration that the nonpayment was "unavoidable" or "unintentional," however, a patent may be reinstated.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.