Co-authored with James Evans, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Explosive growth of antibody technology and therapeutics over the past three decades has driven development of antibody-centric patent case law across several fronts. During this time, the Federal Circuit has decided over 40 cases involving antibodies, spurred by the approval of over 100 therapeutic antibodies.

Over the last decade, in particular, several cases have elucidated the Federal Circuit's approach to construing antibody-related terms in patent claims (claim construction) and the written description and enablement requirements under 35 U.S.C. § 112 for antibody patents. Both claim construction and 35 U.S.C. § 112 requirements are often dispositive in determining infringement and patent validity. Specifically, section 112 sets out, among other things, two requirements for the amount of disclosure an applicant must include in their patent: (1) a description of the subject matter of the invention showing that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention (written description); and (2) a disclosure that enables a person of ordinary skill in the art to make and use the invention without undue experimentation (enablement). This article addresses recent antibody decisions concerning claim construction, written description and enablement.

Claim Construction

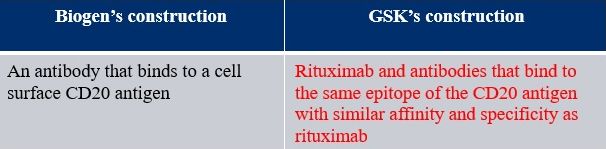

In Biogen v. GlaxoSmithKline LLC, 713 F.3d 1090 (Fed. Cir. 2013), the term "monoclonal antibody" was construed for Biogen's U.S. Patent No. 7,682,612. The parties' proposed constructions are below; the court's construction is in red.

Key to the construction was intrinsic evidence from the patent prosecution. The examiner rejected claims as not enabled that were drawn to the broad genus of anti-CD20 antibodies. The court observed that the examiner found the specification enabled the application of RITUXAN®, RITUXIMAB® and 2B8-MX-DTPA in the treatment of hematologic malignancies, which were in the specification, but did not enable other anti-CD20 antibodies that have different specificity or affinity for the specific epitope. Id. at 1095-1096. The court noted the applicant's response that the specification was enabling for anti-CD20 antibodies with similar affinity and specificity as Rituxan® and that the applicant did not dispute the examiner's reference to a "specific epitope." Id. at 1096.

The court found that GSK's Arzerra® (ofatumumab) product is notably different from Rituxan® (rituximab) in several respects, including that Arzerra® binds to a different epitope and has a much greater affinity for the CD20 antigen. The Federal Circuit affirmed the district court's holding that the applicants limited the claims to antibodies similar to Rituxan® during prosecution. Id. at 1097.

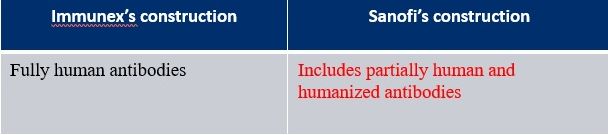

In Immunex Corp. v. Sanofi-Aventis U.S. LLC, 977 F.3d 1212 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the term "human antibody" was construed for Immunex's U.S. Patent No. 8,679,487 on appeal from the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB). The parties' proposed constructions are below; the court's construction is in red.

Here, again, intrinsic evidence was determinative. Immunex cited a prior district court construction limiting the term "human antibody" in the patent to fully human antibodies and to extrinsic evidence such as experts' testimony, product catalogs, and some journal articles to argue "human antibody" had an established limited meaning in the art. The court, however, did not find the arguments persuasive in light of Sanofi's intrinsic evidence. Sanofi relied on statements in the patent specification, including: "The antibodies may be partially human, or preferably completely human" and "Antibodies of the invention include, but are not limited to, partial human (preferably fully human) monoclonal antibodies ...." Id. at 1218-1219.

The Federal Circuit determined that the PTAB was not obligated to justify arriving at a different construction than a district court did in a parallel infringement proceeding. Id. at 1223. The court held that, based on the intrinsic evidence, the PTAB was correct to give little weight to the extrinsic evidence and to construe the claim term "human antibody" as including partially human and humanized antibodies.

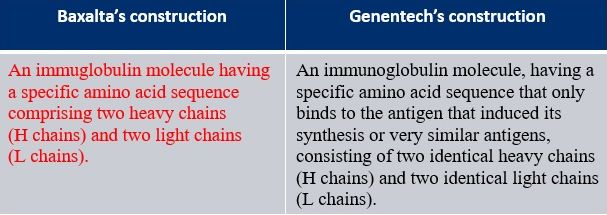

In Baxalta v. Genentech, 972 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2020), the term "antibody" was construed for Baxalta's U.S. Patent No. 7,033,590 (the '590 patent). The parties' proposed constructions are below; the court's construction is in red.

Here, both parties relied on intrinsic evidence. Genentech's construction, which was adopted by Federal Circuit Judge Timothy Dyk sitting by designation in the United States District Court for the District of Delaware, limited "antibody" to a monospecific antibody. Genentech relied on a "definitional" statement in the "Summary of Invention" section of the specification: "Antibodies are immunoglobulin molecules having a specific amino acid sequence.. Each molecule consists of large, identical heavy chains (H chains) and two light, also identical chains (L chains)." Id. at 1344. Judge Dyk found the language definitional and excluded bispecific antibodies, like Genentech's product Hemlibra® (emicizumab-kxwh) (accused of infringing the '590 patent), that do not consist of two identical heavy chains and two identical light chains. See id. Judge Dyk found that bispecific antibodies and antibodies with greater than two heavy and light chains that are disclosed and claimed in the patent are "antibody derivatives" rather than "antibodies" under the patentee's lexicography.

The Federal Circuit, however, began by reviewing the claim language, noting that the plain language of claim 1 does not limit "antibody" to a monospecific antibody and the "dependent claims confirm that 'antibody' is not so limited." Id. at 1345. For example, dependent claim 4 recites, "[t]he antibody . according to claim 1, wherein said antibody . is selected from the group consisting of ... a chimeric antibody, a humanized antibody, ... [and] a bispecific antibody." Id. at 1345-46. (emphasis added). The Federal Circuit rejected Genentech's and the district court's construction which excluded explicitly claimed antibodies and would have rendered the dependent claims invalid. Id. at 1364.

The Federal Circuit heavily weighs intrinsic evidence when deciding claim construction, so parties are wise to focus construction arguments on this type of evidence. Further, where a conflict arises between an arguable term definition in the specification and that term's scope in the claims, maintaining validity of the claims will likely be determinative in the absence of other explicit intrinsic evidence to the contrary.

Written Description

Amgen v. Chugai, 927 F.2d 1200 (Fed. Cir. 1991) and Fiers v. Revel, 984 F.2d 1164 (Fed. Cir. 1993) served as the foundation for written description law, even though they involved conception, not written description. See Burroughs Wellcome Co. v. Barr Labs., Inc., 40 F.3d 1223, 1228 (Fed. Cir. 1994) ("The conception analysis necessarily turns on the inventor's ability to describe his invention with particularity."). Over the past thirty years, the Federal Circuit has built upon the principles established in Amgen and Fiers in deciding nearly a dozen cases on written description grounds involving therapeutic and diagnostic molecules. Examples include: Regents of the Univ. of Cal. v. Eli Lilly, 119 F.3d 1559 (Fed. Cir. 1997), Univ. of Rochester v. G.D. Searle & Co, 358 F.3d 916 (Fed. Cir. 2004), Carnegie Mellon Univ v. Hoffmann-La Roche, 541 F.3d 1115 (Fed. Cir. 2008), Ariad Pharm., Inc. v. Eli Lilly & Co., 598 F.3d 1336 (Fed. Cir. 2010) (en banc), Centocor Ortho Biotech, Inc. v. Abbott Labs., 636 F.3d 1341 (Fed. Cir. 2011), AbbVie Deutschland GmbH & Co., KG v. Janssen Biotech, Inc., 759 F.3d 1285 (Fed. Cir. 2014), Amgen Inc. v. Sanofi, 872 F.3d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 2017), Idenix Pharms v. Gilead Scis., 941 F.3d 1149 (Fed. Cir. 2019) and Juno Therapeutics, Inc. v. Kite Pharma, Inc., 10 F.4d 1330 (Fed. Cir. 2021). Increasingly, written decision cases have involved antibodies. Examples include Centocor, AbbVie, Amgen and Juno.

Regardless of the subject matter, many of the early cases, including Amgen, Fiers, Rochester, Ariad and Centocor, involved invalidating claims because the specification failed to disclose a single example within the scope of the claims. Having firmly established this foundational principle, litigants began presenting the Federal Circuit with the more nuanced question of when are the disclosure of examples and other material sufficient to support the full scope of functionally defined genus claims. The two most recent of these decisions, Idenix v. Gilead and Juno v. Kite, are the subject of our present inquiry.

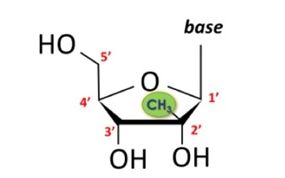

Although Idenix, unlike Juno, is not an antibody case, it deals with many of the same issues that arise in antibody cases-unpredictability of the science, mixed structural-functional claims and vast potential scope-and any treatment of antibody law must take it into consideration. Idenix's claim covered a "method for the treatment of a hepatitis C virus infection, comprising administering an effective amount of a" nucleoside with a methyl on the second carbon in the up position (2'-methyl-up) and many other optional substituents on the other carbons as depicted below. Thus, the claim contained basic structural requirements but permitted numerous substitutions so long as they still resulted in a molecule that could in the right amount provide efficacy in treating HCV infection.

The Federal Circuit considered the validity of this functional claim by evaluating the sufficiency of the disclosure in view of Gilead's accused product (sofosbuvir) which "has fluorine (F) . . . at the 2' down position" and a methyl at the 2' up position, much like the court instructed in Amgen v. Sanofi. 872 F.3d 1367, 1375 ("the use of post-priority-date evidence [of infringing antibodies] to show that a patent does not disclose a representative number of species of a claimed genus is proper"). Idenix's patent, the Federal Circuit held, was invalid for lack of written description because it "provide[d] no method of distinguishing effective from ineffective compounds for compounds reaching beyond the formulas disclosed in the '597 patent." Id. at 1164.

The court in Juno dealt with many of the same issues but in the context of an antibody construct. The broad claim covered a three-part "nucleic acid polymer encoding a chimeric T cell receptor" with a (1) "zeta chain portion comprising the intracellular domain of human CD3 ? chain"; (2) "a costimulatory signaling region" including a specified sequence; and (3) "a binding element" such as an antibody fragment (scFV) that interacts with a target. The specification, however, only disclosed two examples of suitable "binding element[s]" and provided no details concerning even these examples other than their alphanumeric designations. The specification, according to the Federal Circuit, failed to disclose representative species because the two examples did "not provide information sufficient to establish that a skilled artisan would understand how to identify the species of scFvs capable of binding to the limitless number of targets." The "mere fact that scFVs in general bind" was not enough. Nor did the disclosure identify common structural features because the only disclosed commonalities failed "to disclose a way to distinguish those scFVs capable of binding from scFvs incapable of binding those targets."

Enablement

Like written description, the law of enablement has seen a new shift in focus recently. Early cases, such as Hybritech Inc. v. Monoclonal Antibodies, Inc., 802 F.2d 1367 (Fed. Cir. 1986), In re Wands, 858 F.2d 731 (Fed. Cir. 1988) and Johns Hopkins University v. CellPro, Inc., 152 F.3d 1342 (Fed. Cir. 1998), tended to uphold the validity of antibody claims; however, in none of these cases did an adverse party raise significant enablement challenges. Functionally defined genus claims have been subject to increasing scrutiny and found wanting in the context of small molecules and nucleic acids. Examples include: Wyeth & Cordis Corp. v. Abbott Labs., 720 F.3d 1380 (Fed. Cir. 2013), Enzo Life Scis., Inc. v. Roche Molecular Sys., Inc., 928 F.3d 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2019) and Idenix Pharms. LLC v. Gilead Scis. Inc., 941 F.3d 1149 (Fed. Cir. 2019). Then, in the past two years, cases filed in the District of Delaware produced decisions invalidating functionally defined antibody genus claims for lack of enablement.

In Morphosys AG v. Janssen Biotech, Inc., Judge Stark (who now sits on the Federal Circuit bench) found a claim to antibodies that bind to a specified epitope on the CD38 protein invalid for lack of enablement on a summary judgment motion because the four disclosed antibodies and other teachings were insufficient to support the full scope of the claim. Each of the Wands factors weighed against validity. Most importantly, the examples were "unhelpful" because they failed to teach "how to predict from an antibody's sequence whether it will bind to CD38"; therefore, the skilled artisan could not extrapolate from the examples to other claimed embodiments without engaging in unpredictable experimentation. The fact that generating potentially covered antibodies and testing them was routine was inconsequential in view of the challenge faced by the skilled artisan to determine which of the vast number of candidate antibodies possessed the required functional properties.

The Morphosys decision, which was never appealed, was followed by two Federal Circuit decisions. Like Morphosys, these decisions considered whether functionally defined genus claims were enabled by disclosures which required the skilled artisan to engage in unpredictable trial-and-error testing to identify which of many candidates fell within the claims' scope.

In Idenix, discussed above in the "Written Description" section, the Federal Circuit also found the claims wanting for lack of enablement. The patentee's expert admitted that it was difficult "'to make a compound and determine whether or not it is active' against [hepatitis C]," and that "'you don't know whether or not a [compound] will have'" the claimed function "'until you make it and test it.'" The specification "contain[ed] some data showing working examples" and "identif[ied] a 'target' to be the subject of future testing," while leaving a skilled artisan to "'engage in an iterative, trial-and-error process to practice the claimed invention.'" There were, however, billions of compounds that "literally [met] the structural limitations of the claim," and at least "'many, many thousands' of candidate compounds exist[ed]" even under the patentee's theory that a skilled artisan "would not [modify the compounds] at random" but instead would use "common sense, the claims, and the specification as guidance [to] focus on a narrow set of candidates." The court determined that, even if the jury "could have concluded that synthesis of an individual [compound] was largely routine," the claims were "invalid for lack of enablement."

Amgen v. Sanofi involved similar claims, in that they covered a broad, functionally defined genus; however, these were, as in Morphsys, directed to antibodies. Amgen's patents claimed a genus of monoclonal antibodies that bind to a particular antigen (PCSK9), bind to a specified location on that antigen (one or more identified amino acid residues) and block the naturally occurring PCSK9-LDL-receptor interaction. The specification disclosed 26 examples and, according to the patentee, a "roadmap" for finding more antibodies within the scope of the claims.

Amgen argued that its claims actually covered a very small number of antibodies; however, the court was not concerned merely with disputes over "the exact number of embodiments falling within the claims." Instead, it held the court must also consider "functional breadth" and found Amgens' claims functionally "broad" when compared to the "narrow" disclosure. "For example, there are three claimed residues to which not one disclosed example binds. . . . And although the claims include antibodies that bind up to sixteen residues, none of Amgen's examples binds more than nine."

Undisputed evidence of unpredictability-despite the fact that making and testing antibodies was routine-also weighed in favor of non-enablement. "[T]his invention is in an unpredictable field of science with respect to satisfying the full scope of the functional limitations. One of Amgen's expert witnesses admitted that translating an antibody's amino acid 'sequence into a known three-dimensional structure is still not possible.'. Another of Amgen's experts conceded that 'substitutions in the amino acid sequence of an antibody can affect the antibody's function, and testing would be required to ensure that a substitution does not alter the binding and blocking functions.'"

The court upheld the district court's grant of JMOL invalidating Amgen's claims for lack of enablement because "the evidence showed that the scope of the claims encompasses millions of candidates claimed with respect to multiple specific functions, and that it would be necessary to first generate and then screen each candidate antibody to determine whether it meets the double-function claim limitations."

Conclusion

As the patent case law surrounding antibodies and other therapeutic molecules continues to mature, players in this space increasingly benefit from a body of law that will permit greater predictability in outcome.

James Evans, Ph.D., is Director, Dispute Resolution at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. He has a Ph.D. in Immunobiology and focuses his practice on biotechnology and pharmaceutical patent litigation and oppositions worldwide. Prior to joining Regeneron, Dr. Evans had over 10 years of experience representing numerous pharmaceutical companies in ANDA and BPCIA preparation and litigations and patent challenges before the United States Patent and Trade Office and oppositions before the European Patent Office.

This article was originally published on PLI PLUS

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.