I. INTRODUCTION

Sovereign governments in Asia, Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere are increasingly turning to sukuk (Islamic or sharia-compliant bonds) to meet their financing needs. These issuers include several countries experiencing debt challenges, such as Pakistan, Egypt and Nigeria. However, many financial market stakeholders are less familiar with sukuk compared to traditional debt instruments. This research note seeks to demystify sovereign sukuk, from both market and legal perspectives.1

Part I of this paper delves into what sovereign sukuk are, examining the ways in which sukuk generate income for investors without relying on interest or contravening Islamic prohibitions. Part II provides an overview of the market for sovereign sukuk. It identifies and discusses the market participants (i.e., issuers, investors, and underwriters), their motivations and how sukuk yields compare with those on conventional bonds. Part III discusses how sukuk are likely to be treated if an issuing government defaults on or restructures its debt.

A few of the key findings in this note are as follows.

- Sovereign sukuk are currently the most predominant form of

sukuk finance, comprising approximately $400 billion of the total

sukuk market of $730 billion at the end of 2021. If one includes

sukuk issued by state-owned or state-controlled entities, the de

facto share of sovereign sukuk in the total would be even

greater.

- The cost to sovereigns of financing from sukuk is often lower

than that of financing from conventional international sovereign

bonds. This is especially so for sovereigns with lower credit

ratings and higher borrowing costs, suggesting that such countries

may have particular opportunities to tap sovereign sukuk for their

financing needs.

- This "sukuk discount" does not stem from any de jure or de facto seniority to other obligations of the sovereign. Neither does it appear to stem from any sukuk-specific legal provisions that would pay out sukuk holders over holders of other bonds in the event of a default.

Taken together, these findings suggest that sovereigns, especially those that are facing higher borrowing costs, have a useful opportunity to tap sukuk finance for meeting their economic development and other financing needs. This paper's analysis also suggests that potential investors in sukuk need not fear being subordinated to conventional bondholders of the sovereign. We hope that this work will help demystify sharia-compliant sovereign finance, especially at a time when a growing number of countries in the developing world have large financing needs.

II. THE STRUCTURE OF SOVEREIGN SUKUK

A. Overview

Sovereign sukuk are financial instruments that replicate the economic effects of traditional sovereign bonds2 while adhering to Islamic law (i.e., sharia). Sharia prohibits riba (interest), gharar (excessive uncertainty) and maysir (speculation). In addition, sharia disallows investments in certain prohibited industries (e.g., alcohol, pork, gambling). Accordingly, sukuk securities represent ownership shares in tangible assets and the rights to the profits from those assets, rather than receivables from debt obligations. Dollar-denominated sovereign sukuk are typically structured as trust certificates under English law.3

For investors, holding a sukuk is similar to holding a bond. Both instruments are contractual obligations whereby the government promises to both:

1. Periodically pay holders a certain amount (i.e. returns on assets), and

2. Repay the nominal value of the instrument at a certain future date (i.e. return of asset).

In the case of a bond, the periodic payment is called the "coupon," and the nominal value is called the "par" or "face" value. In the case of a sukuk, the periodic payment is called the "periodic distribution amount," and the nominal value is called the "dissolution distribution amount." Sovereign bonds and sukuk can each be designed as either fixed- or floatingrate instruments, but both are usually fixed-rate.

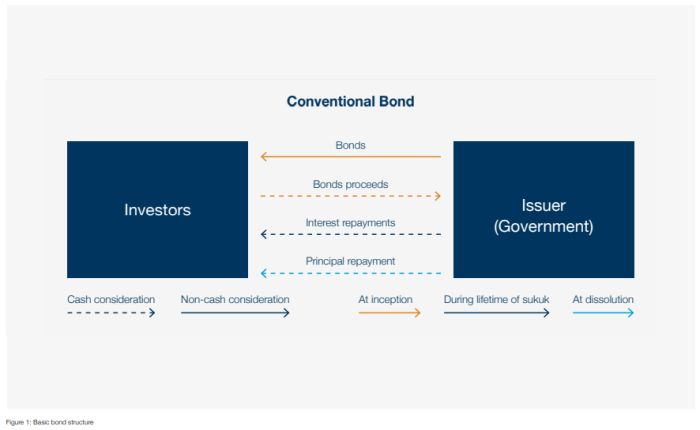

Despite these similarities, the underlying structures of bonds and sukuk differ significantly. Bonds represent a bilateral relationship between an issuer and investors. Governments sell the bonds to investors in exchange for a promise to pay back interest and principal. These obligations are typically not secured against or otherwise tied primarily to state assets.

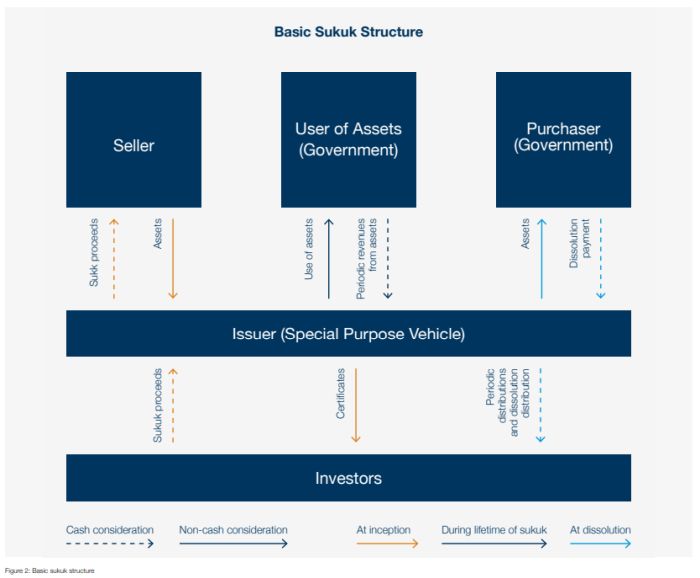

Sukuk involve a more complex set of contractual relationships and derive their value—at least contractually—from specific assets. Under a sukuk arrangement,4 the government creates an offshore special purpose vehicle (SPV), which issues sukuk certificates to investors in exchange for cash. The SPV then uses those proceeds to purchase one or more assets, often from the government but sometimes from a third party. The certificates held by investors represent equal and undivided shares in the ownership of those assets purchased by the SPV. Accordingly, the SPV periodically distributes the returns generated by (or contractually derived from) the assets to investors. At a pre-specified dissolution date, the government purchases the assets back from the SPV, and the SPV distributes the proceeds from this sale along with any remaining surplus in the SPV (net of costs) to investors.

International sovereign sukuk are almost always structured as trust certificates under English law, whereby the SPV serves as the trustee of the investors and manages the sukuk assets on their behalf. Typically, the trustee appoints a third-party delegate to exercise its contractual rights, including taking enforcement action against the government in the event of default. Otherwise, an SPV wholly owned by the government would be unlikely to act against the government for the benefit of its investors.

Many civil law countries issuing local currency sukuk cannot rely on the concept of trusts, since their domestic legal regimes do not recognize them. Therefore, in certain countries alternative civil law structures have been developed to allow sukuk to be carried out under domestic laws. Some such jurisdictions have passed bespoke legislation to enable the issuance of sukuk under domestic law. For example, Turkey's sukuk regulation allows for the creation of "asset-lease companies," a specific type of SPV solely intended for the purpose of issuing sukuk.

Figure 2 depicts a stylized structure of a sovereign sukuk. Within this general structure, there is considerable variation both in the ownership rights transferred to investors and in the ways in which the underlying assets generate profits.

To view the full article click here

Footnotes

1. The analysis in this paper relies on interviews with various experts in Islamic finance, prospectuses from publicly issued sovereign sukuk, sukuk yield data provided by Bloomberg and various secondary sources, including news articles and academic literature. We would like to thank colleagues at Rand Merchant Bank; the International Monetary Fund; White & Case; Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer; DLA Piper; Tellimer; Clifford Chance; Curtis, Mallet-Prevost, Colt, & Mosle; and Linklaters for their input. With that said, this paper solely reflects the views of the authors. None of the opinions or information herein should be attributed to anyone else.

2. Note that sukuk originated by corporations or financial institutions are often designed with more equity-like features. However, publicly issued sovereign sukuk are all designed as fixed- income- instruments at the time of writing.

3. English law and New York law are commonly chosen as the governing law for international (non-local currency) bond issues. In the case of sukuk, English law has emerged as the convention

4. The description that follows is a generalization. Certain sukuk arrangements may diverge from this general outline.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.