Foreword

Investment managers specialising in providing low cost index-tracking products are increasingly able to generate similar returns to those of traditional active managers. Providing "beta" returns at "alpha" cost is no longer an option.

Traditional active managers face a choice between becoming more efficient beta providers or differentiating through higher alpha returns. Some may choose a third way, moving towards a "total solutions" model to specialise in providing both types of return under one roof. There are however operational challenges in doing so. Traditional active managers must achieve the more cost-efficient, standardised and scaled-up processes that are required for the provision of beta returns, without stifling the autonomy and agility required to outperform the market for alpha.

In making such strategic decisions, traditional active managers need to gain a greater understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. Firms should use this analysis to create the right structure and capabilities to fulfil their chosen strategy. Winning investment managers are likely to be those who have the capacity to align their business strategy and organisational structure to deliver against their chosen investment approach. This study is intended to provide some practical steps for investment managers looking to succeed in a market polarising between alpha and beta.

Eliza Dungworth

UK Head of Investment Management

Executive summary

Caught in the middle New technologies and innovations have paved the way for investment firms to provide low-cost index-tracking products. Such products can give similar beta returns to those of traditional active managers – but at a lower cost. Investors seeking beta have therefore swung towards passive index-tracking products like ETFs:

- The value of global mutual fund inflows (excluding ETFs, which are typically passively managed) fell from $1,400 billion in 2007 to -$121 billion in 2008.

- Asset values of ETFs rose from $796.7 billion in 2007 to a peak of $1,036 billion at the end of 2009, a CAGR of 14.0%.

Investors have also required greater performance from their alpha providers, stretching alternative investment managers and causing a shake-out among underperforming alpha funds. For instance:

- The number and value of private-equity funds has fallen sharply, dropping from 1,624 funds of funds with asset values of $888.4 billion (Jan 2009), to 1,561 funds with assets of $698.5 billion (Jan 2010).

- A similar trend is seen within the hedge funds sector over 2007-2009.

The market is therefore polarising: Beta providers focus on cost, efficiency, diversification and liquidity through enhanced scale; while alpha providers develop unique active management capabilities based on alternative investment strategies.

Providing 'beta' returns at 'alpha' prices is no longer an option. Many traditional active managers face a fundamental choice: specialise in the provision of either alpha or beta returns; or offer investors a 'total solution' providing both specialisms under one roof.

Traditional active managers providing total solutions may find it hard to achieve the more cost-efficient, standardised and scaled-up processes required for beta returns without, at the same time, stifling the autonomy and agility essential for alpha returns.

Different capabilities for alpha and beta

The infrastructure required to deliver beta (passive) and alpha (active) returns is different. As investment managers have become specialised, so the infrastructure required to deliver passive beta-tracking and alpha-based active funds has specialised too. For example:

- Passive managers seek to provide high-volume, low-cost, liquid index-tracking products. They require an autonomous, coded, front-end IT trading platform capable of sending automated trade messages to counterparties to match the value of tracked indices. Such automation is crucial given the volume of trades on highly liquid indices.

- Active managers require differentiated strategies to outperform the market. Requirements for success may include bespoke functions and data platforms that can enable multiple, more complex investment techniques. Processes are typically tailored, with investment strategy generated by sophisticated primary research. Face-to-face relationships with brokers are often required in order to facilitate access to the best prices or inventory.

Rethinking operating models

We identify three investment management business operating models:

Universal: A large organisation operating as 'one-firm' to benefit from both economies of scale and scope.

Multi-strategy: Distinguished from the one-firm universal model by the idea that fund managers work best in semi-autonomous units under an umbrella. Boutique: Differentiated by the significant autonomy given to divisions, people and processes giving rise to differentiated propositions or returns.

Investment managers should think carefully about the infrastructure required to optimise both alpha and beta under one roof.

A selective approach should be taken in deciding which divisions, functions and processes should be given greater autonomy or integrated/consolidated:

- Beta: simplify, standardise and scale-up in order to achieve lower costs and a competitive edge.

- Alpha: allow divisions and functions autonomy. Integrate only certain functions (such as risk, finance & controls and IT), allowing divisions (or funds) their own bespoke infrastructure that can work in a specialised and integrated way for enhanced speed to market and a more tailored approach.

Practical steps for change

In response to this polarising market, traditional active managers can take five practical steps:

1. Determine the strategic agenda and assess core competencies.

The shift to greater specialisation and more tailored products may leave organisations disenfranchised (as they become increasingly open to the threat of new entrants). Firms are required to reappraise both their role and their propositions within the value chain.

2. Map out the current operating model.

Investment managers may not have the people, processes and/or technology to deliver on their current strategy, or to meet the requirements of any shift towards a new offering. This may be due to constraints in the current operating model. Understanding the degree to which operational capabilities can support shifting strategies is essential.

3. Move to a more variable cost base.

Revenues are variable, and may decline while costs remain fixed. This may be due to investment managers' retaining product-manufacturing and distribution capabilities in-house. Firms should consider outsourcing non-core functions, moving them to variable-cost agreements and shared services.

4. Integrate common processes for efficiency & control.

With each business unit typically operating its own infrastructure, current operating models can be inefficient. This can lead to sub-optimal operations and the duplication of processes. Integrating common processes may improve a firm's operating efficiency and risk governance and controls through a more standardised and transparent approach.

5. Allow autonomy where appropriate.

While integrated functions and divisions are key to achieving greater operational efficiency and control, some divisions (funds) are currently struggling to operate within the boundaries of their firm's operating model (which seek a standardised approach to many processes). Alternative funds seeking alpha returns require autonomy for their investment professionals in order to make unique judgements in their markets. Therefore a select approach to integration is required where certain processes are tightly controlled on an enterprise-wide basis while others are given greater autonomy.

Caught in the middle

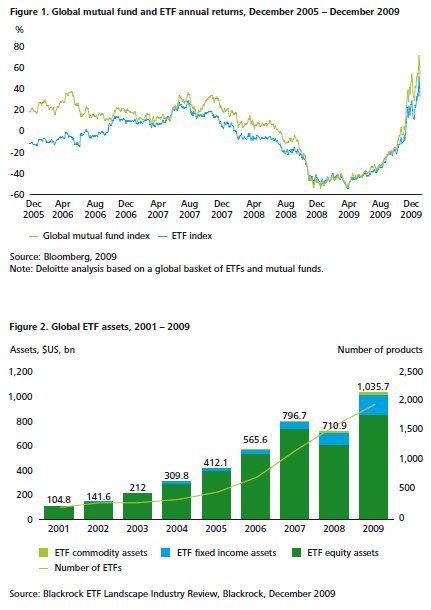

Traditional active managers are in danger of finding themselves caught in the middle of a market that is polarising. Thanks to new technologies and innovations, specialised passive investment firms have been able to offer index-tracking products that give similar beta returns to many traditional active managers – but at a lower cost. Figure 1 shows the gross average annual returns for a selection of global mutual funds (which are typically actively managed). Since the end of 2008, these have been only marginally higher than those of more passive products such as exchange traded funds (ETFs).1 Indeed, due to higher fees, net post-fee returns of active investment managers can be lower than some passive indexing/beta products.

Investors have become increasingly aware that the fees of traditional active managers may have eaten into their net returns. This has persuaded them to migrate away from actively managed propositions towards more passive products, like ETFs. For instance, the value of global mutual fund inflows (excluding ETFs) fell from $1,400 billion in 2007 to -$121.1 billion in 2008, subsequently recovering to just $13.3 billion up to the third quarter of 2009.2 At the same time, Figure 2 shows that investors seeking beta returns have swung towards lower risk, lower cost, passive index-tracking products. Total ETF asset values rose to a peak of $1,035.7 billion at the end of 2009, from $796.7 billion in 2007, a CAGR of 14.0%.

The fall-out for traditional active managers from these changes has been significant. They have suffered from declining margins and pressure on fees as investors have paid less and less for beta returns, and as lowmargin index-tracking products have continued to make a significant contribution to traditional active managers' overall returns.

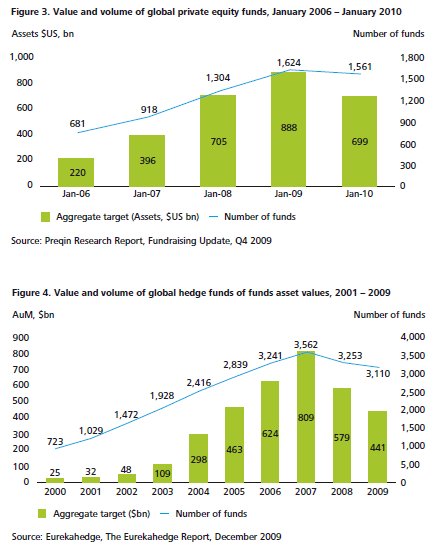

Even at the alpha end of the market, investors have demanded sustained high returns at lower cost. This has stretched alternative investment managers and caused a shake-out among underperforming alpha providers. Figure 3 indicates that the number and value of private-equity funds has fallen sharply. For instance, the market has dropped from 1,624 funds of funds with assets of $888.4 billion (January 2009), to 1,561 funds and assets of $698.5 billion in January 2010. Figure 4 shows a similar trend within the hedge funds sector, illustrating a decrease in the number and value of global hedge funds of funds from 2007 to 2009.

Some traditional active managers have attempted to compete in the increasingly specialised hedge-fund and private-equity sector, where higher quality providers have typically survived.

As each investment management firm navigates a new course in response to these challenges, it is clear that the market is polarising. Beta providers have focused on achieving greater cost effectiveness, diversification and liquidity through enhanced scale. In contrast, other leading managers have developed their active management capabilities to deliver absolute returns, based on alternative investment strategies.

At the alpha end of the market, some investment managers have struggled to justify charging higher fees than those of beta providers. Those who can consistently deliver outperforming returns are most likely to succeed.

How should traditional active managers respond to these changes in investor preferences and the subsequent shifts in the competitive landscape? Many now face a fundamental choice: to specialise in the provision of either alpha or beta returns or attempt to provide both under one roof.

Different capabilities for alpha and beta

The decision to compete on alpha, beta or both is complex. As the infrastructure required to deliver passive (beta) and active (alpha) returns is very different, investment managers are required to have a full understanding of their current organisational capabilities. The panel below illustrates key differences between the capability requirements of active and passive managers.

Passive managers seek to provide high-volume, low-cost, liquid index-tracking products. They aim to minimise operational errors and inefficiencies and to gain economies of scale in order to avoid any erosion of profits in a lower margin market. Processes are typically simplified and standardised. This is to improve operational efficiency within a centrally controlled, scalable infrastructure that is based on a data platform spanning multiple markets and products. Processes that can be simplified and scaled up include equity trading and execution for major markets and sectors, such as the FTSE 100 and the MSCI World Index.

Crucial requirements for success may include an autonomous, coded, front-end IT trading platform that is capable of sending automated trade messages to brokers and other counterparties to match the value of the index. Functions/processes need to be scalable in order to facilitate the automation required for enhanced operational efficiency among passive managers. Such automation is crucial given the volume of trades on highly liquid indices.

Active managers require differentiated strategies to outperform the market. Their products and instruments may be more complex, requiring specialised high-end research capabilities. These in turn require sophisticated data systems and trading platforms. Functions are often more integrated, enabling people and processes to come together for a faster, more tailored response to client and market changes. This enables portfolio managers and traders within long/short equity hedge funds to develop proprietary positions on individual sectors or stocks, in turn, facilitating unique positions to achieve an excess return. Product development and client-servicing capabilities are typically more bespoke, with greater autonomy often granted to individual fund managers. This is in contrast to the standardised, scalable processes of passive beta providers.

Crucial requirements for success may include having more sophisticated functions and data platforms in place to enable multiple, more complex investment techniques. Processes are more tailored, consisting of sophisticated primary research and analysis to generate an appropriate investment strategy. This often involves face-to-face relationships with brokers in order to facilitate access to the best prices or inventory. In addition, it requires a flexible trading platform which can encompass a broader range of instruments that can be tailored to a specific proprietary trading strategy. For example, the use of bespoke or OTC derivatives to achieve efficient exposure to a particular market or to hedge a specific position requires such flexibility.

As the propositions of investment managers have become more polarised and specialised, so the infrastructure required to deliver passive beta-tracking and alpha-based alternative funds has become increasingly specialist. Firms face difficulties in specialising at either end of the market as the capabilities required increasingly diverge. Those attempting to compete in both (increasingly specialised) markets are struggling to find an optimum business operating model that can accomodate both long and short positions (i.e. to achieve both alpha and beta returns).

Traditional active managers will find it hard to achieve the more cost-efficient, standardised and scaled-up processes that are required for the provision of beta returns, without at the same time stifling the autonomy and agility that are essential to outperform the market for alpha. Although operationally difficult, there are forces that are pushing investment managers towards the delivery of "total solutions" (i.e. the provision of both alpha and beta returns). UCITS III, the EU directive on "Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities", has enabled traditional active managers to deploy shorting and other over-the-counter (OTC) derivative techniques to enhance overall returns.

Rethinking operating models

Investment managers face challenges in building the capabilities required to compete on a more specialised basis at both ends of the market. Shifting to either alpha or beta specialisation entails a choice about what should be defined as their core business, and which capabilities should be built, acquired or divested.

We identify three different types of current business operating model that bring together strategy, proposition and operational considerations:

- Universal The largest investment management firms, those that are "universal", benefit from both economies of scale and scope. They diversify fully across product ranges, from passive through to traditional and alternative actively-managed funds. Their organisation aims for integrated functions and processes. Customers/clients can potentially benefit from this one-stop-shop approach, offering a single point of contact along with diverse product-ranges and sophisticated global research capabilities. When executed well, an integrated approach can contribute to building a high-quality brand, which is increasingly important in today's market where investors have increasingly embarked on a flight to quality.

- Multi-strategy The multi-strategy model is distinguished from the integrated one-firm universal model by the idea that investment professionals operate best under differentiated, semi-autonomous units under an umbrella. The benefits of scale and scope are exploited from within the parent company. This may be through shared financing and fund-administration functions, or through asset-servicing capabilities. The organisation is characterised by autonomous funds and fund groups which have independence in portfolio management and trading. At the same time they are able to leverage the existing infrastructure of the parent group, most notably its asset- servicing, legal and regulatory capabilities. This model aims to enable a number of fund managers to focus on investment decision-making and performance by providing a scalable, shared and cost-efficient infrastructure.

- Boutique The boutique firm is distinguished by the extent to which its divisions, people and processes enjoy organisational and cultural autonomy. Such firms typically rely on partners and service providers to achieve scale and scope. This is at a higher per-unit operational cost than is incurred by universal and multi-strategy firms. This can often be outweighed by higher investor returns and market out-performance. Outperforming the market becomes more difficult as the value of firms' assets under management increases.

Bringing together the infrastructure required for alpha and beta into one model requires investment managers to simplify, standardise and scale-up in order to achieve lower costs and a competitive edge. At the same time, functions and divisions concerned with the provision of alpha services often require a greater degree of autonomy and flexibility. Therefore a selective approach should be taken: integrating only certain functions (such as risk, finance and IT), while allowing divisions (or funds) their own bespoke infrastructure that can work in a specialised and integrated way for enhanced speed to market and a more tailored approach.

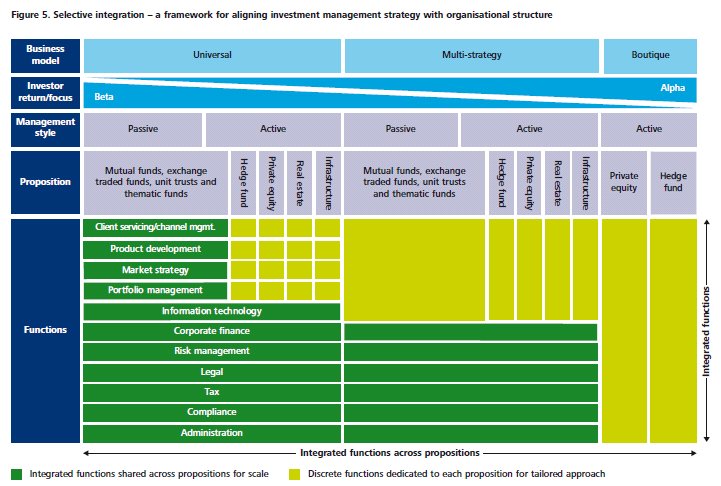

Figure 5 illustrates a framework that may be useful in guiding decisions about which funds, functions or processes can be integrated for gains in efficiency (and control), and which should be operated discretely.

Boutique managers and those with significant alphabased active management are most likely to include operations that deliver tailored services or a differentiated, market-beating performance. Each proposition typically has a suite of dedicated functions that work together to achieve speed to market or more tailored delivery. Within boutiques, functions are rarely integrated across propositions due to the specialised nature of work. Each proposition therefore has its own discrete set of functions.

A universal model is typically characterised by highly scaled processes, a wide distribution network, and an integrated, one-firm approach. Functions are typically consolidated within the universal model (serving several divisions/propositions at the same time), with processes simplified and standardised to enable them to be scaled-up. Within the multi-strategy model, some functions can be selectively integrated across propositions while others remain specific and bespoke to each proposition (i.e. are operated discretely).

Functions such as client servicing/channel management, product development, market strategy and portfolio management are kept largely separate (operated discretely) for each division. However, functions such as corporate finance, risk management, legal, tax, compliance and administration, may be integrated across several propositions/divisions.

Deloitte argues that information technology should be integrated within the universal model, while remaining divisionally separate within the multi-strategy model. The boutique model, by contrast, is characterised by highly integrated functions spanning front, middle and back office operations.

Aligning the strategies of investment managers (business models, investor returns, management styles and propositions) to an appropriate operating structure is a key principle for success.

Practical steps for change

There are five practical steps that traditional active managers can take as they respond to the challenges and opportunities of a market which is polarising. Each investment management firm will have its own starting point, and no one size will fit all.

1. Determine the strategic agenda and assess core competencies

The shift to greater specialisation and more tailored products may leave organisations disenfranchised (as they become increasingly open to the threat of new entrants). Firms are required to reappraise both their role and their propositions within the value chain. They then need to assess how and where to compete in the market.

Operating models suffer from excessive complexity. This is due to firms pursuing growth, either organically or inorganically, through an extension of asset classes and product ranges.

The result is operational inefficiency and process duplication. Operations remain relatively un-integrated, with legacy IT systems often still in place from previous M&A activity. There is a need to combat these issues by streamlining disparate and/or extended product ranges. Investment managers should consider the following steps:

- Determine their future strategy and business model by means of a review that could help them to better understand competitors, client segments, product and service strengths (and weaknesses), along with brand perceptions and other differentiators.

-

- For a 'total solutions' provider, this may require a better understanding of the firm's ability to allocate assets through highly diversified but integrated and scaled processes. For those seeking to outperform the market, integrated functions, an effective risk culture and tailored technology and research capabilities may be vital in determining the structure of any future business model. In addition, a good understanding of the current client base and the strategy for accessing other potential clients is required. Similarly, firms need to examine client perceptions of their brand relative to competitors. Plugging gaps in capabilities and/or market segments may well involve organic growth or a strategic acquisition.

- Assess strategy in light of the firm's current operational capabilities.

-

- Conduct an exercise to determine how current operations may frustrate or facilitate future business plans. A plan to plug any gaps in operational capabilities may involve organic change or strategic acquisition. The likely success or failure of post-merger integration (PMI) should be thought through in any decision to build capabilities other than organically.

- Simplify operating models through a renewed focus on core competencies. Activities should be redefined in line with criteria set out by the strategic review.

-

- For beta-related propositions, core competencies may be largely concerned with scalable processes to achieve higher volumes. For alpha, however, competencies are likely to include the use of sophisticated investment techniques, along with access to real-time data to help outperform the market. A decision on whether to compete on operational efficiency or on market outperformance will be required in defining core business. Geographic scope should also be considered, along with a decision to focus on emerging markets or mature markets.

- Be aware that, in more volatile markets, brand plays a key role in attracting and retaining investors.

-

- Achieving the expected investment performance level is critical to building and maintaining a strong brand. Investment firms also need to determine whether they can deliver specific products competitively to their investor base, and whether these products align with the character of their broader "brand permission".

- Simplify propositions (products and services) to reduce complexity.

-

- Determining whether to provide either alpha or beta returns (or both) will be critical. A more targeted market approach should emerge from an appropriate investor segmentation strategy. An assessment of all product and service offerings may be required, stripping out the less profitable activities and focusing on the most profitable (and least capital-intensive).

2. Map out the current operating model

Investment managers may not have the people, processes and/or technology to deliver on their current strategy, or to meet the requirements of any shift towards offering more specialised alpha/beta products. This may be due to constraints in the current operating model. Managers should therefore look to:

- Understand the impact of any changes on the current operating model - for instance, the effect of moving to a new asset class, strategy or product suite. In doing so, there are two key steps:

-

- Establish the starting point for the current operating model by assessing its structure and determining capability gaps. Find out where the operating model does not facilitate the delivery of the current proposition.

- Assess the potential impact of any strategic re-positioning; and then determine the approach by which obstacles to the execution of the new strategy can be overcome. Building new capabilities may require a decision on whether to expand organically or otherwise. Related to this, investment managers may need to determine the extent to which they should integrate new acquisitions or keep them separate. Their decision will be influenced by each business unit's need for autonomous or scaled operations.

- Determine which functions are typically kept in-house, by assessing the potential use of shared service providers/centres of excellence or of outsourcing. The overall aim here will be to minimise fixed costs.

3. Move to a more variable cost base

Revenues are variable and may decline, while costs remain fixed. This may, in part, be due to investment managers' inclination to keep product-manufacturing and distribution capabilities in-house. Steps required include:

- As a general principle, non-core functions should be outsourced, while core functions should be kept in-house.

-

- To achieve greater flexibility, third party suppliers should be moved to variable-cost agreements wherever possible.

- There should also be a renewed focus on renegotiating with vendors.

- Evaluate the use of shared service providers and/or centres of excellence, determining which functions to optimise or release from the core operating model.

- Mitigate against a fixed-cost base by increasing the contribution to revenues of fee-based areas, such as advisory.

- Review the role of performance-related pay (PRP).

-

- Where compensation is not strongly linked to performance (especially among beta-based firms or divisions), PRP should be enhanced to improve the alignment with investors' interests and to help resolve any conflict between volatile earnings and the fixed cost base.

4. Integrate common processes for efficiency & control

Current operating models can be inefficient, with each business unit typically operating its own infrastructure. This can lead to sub-optimal operations and process duplication. Where the key differentiator is process efficiency and the sophistication of technology – as opposed to human capital – investment managers might consider the following steps:

- Determine which functions to integrate:

-

- Assess the extent to which functions that typically do not require as much flexibility and/or autonomy can be integrated. Processes that are not individually tailored to specific products, investor segments or geographies (and that can be shared across divisional units) should be considered for integration. Examples may include finance, legal, tax, risk management and compliance: areas that are able to achieve relatively more standardised processes that can be shared across the whole organisation.

- The benefits of integration can be significant where acquisitions have been made without any significant post-merger integration (PMI) activity.

- Integrate risk-based processes and functions to achieve standardised, measurable and transparent risk governance and control across the enterprise.

5. Allow autonomy where appropriate

Alternative investment firms seeking alpha returns are primarily people-based businesses. Within them, investment professionals require autonomy in order to make unique judgements regarding their markets. Some divisions (funds) are currently struggling to operate within the boundaries of their firm's operating model (which seeks a standardised approach to many processes). This can result in a lack of flexibility, causing a slower, less tailored response.

There is a need for greater flexibility so as not to stifle the capabilities required for the provision of alpha returns. It is important that functions for tailored propositions are kept separate from more standardised platform-based processes in order to allow autonomy and specialisation where needed. At the same time, firms need to seek out operational efficiencies that may be inherent in processes that are not highly scaled.

Therefore a selective approach should be taken where certain processes are tightly controlled on an enterprise-wide basis while others are allowed autonomy from more standardised enterprise-wide systems and processes.

Investment managers should:

- Be selective when dealing with units that require greater autonomy; only integrating processes where appropriate. For instance, integrated functions such as risk management and tax may offer significant support from an enterprise-wide platform:

-

- Keep separate those functions requiring greater levels of flexibility. Examples may include client servicing, product development and market strategy.

- Establish at group level policy, to determine the treatment of those divisions which should be operated on a more autonomous basis.

- Encourage greater integration of functions for improved speed to market for example, foster a culture of enhanced trust and co-operation for critical functions within alpha divisions.

Conclusion

Investment managers are being called upon to respond to an industry in flux. Many face the combined pressure to achieve operational efficiency while at the same time distinguishing themselves from their competitors through market outperformance.

Deloitte has identified three prevailing business models: universal; multi-strategy; and boutique. Each model has its own merits and challenges to be overcome.

The universal model appeals to those seeking to leverage their client-base and distribution capabilities – for those who excel at providing a "total solution" for their clients. The multi-strategy model competes by leveraging valuable administrative functions and infrastructure in support of a range of targeted investment divisions. The boutique model generates competitive advantage by differentiating through its people and flexibility to attain more unique investment positions.

Integrating functions and divisions may be crucial to achieving greater consistency in propositions and operational efficiency, along with improved risk and control procedures. Investment managers should, however, avoid the temptation to go for wholesale integration. An appropriate level of divisional autonomy may be required, so that the capabilities needed to outperform the market are not stifled.

The investment landscape changed with the introduction of specialist, low cost beta trackers. Providing beta returns at 'alpha' cost is not an option. Investment firms face a series of strategic choices: specialise in alpha or beta, or provide both specialisms under one roof. For success, each choice has a series of significant operational considerations that should be taken into account. Decisions made now will shape the look and feel of the investment management landscape for years to come.

Glossary

This report uses the following definitions:

Passive

Exchange traded fund (ETF): An investment product representing a basket of securities, engineered to track an index such as the FTSE 100 or S&P 500. ETFs are traded on an exchange in a similar manner to stocks, with the price changing throughout the day. ETFs are only available to investors through brokers or advisors.

Passive funds merely aim to track the market in which they are invested. Passive investments may include buyand- hold strategies (or less regular buy- and-sell activity).

Thematic funds: Thematic funds are designed to identify themes, based either on global trends or more specific criteria. Themes are typically generated through analysis of profitable long-term trends.

Active

Active fund managers research the market in order to guide decisions about whether to buy or sell assets in order to outperform the market – reflecting their belief that it is possible to profit from mispriced securities (contrary to the efficient-markets hypothesis). Active managers place greater emphasis on high-end analytical research and judgement to make forecasts, while coming to a decision about whether to buy, hold or sell.

Hedge funds: Hedge Funds all aim to maximise the value of absolute returns, by outperforming indices. Altogether more aggressive strategies than those available to mutual funds are pursued. These typically include short-selling, leverage, arbitrage, program trading, swaps and derivative instruments.

Private equity: Shares in mature private companies or start-ups (venture capital). Investors typically expect to earn a higher equity risk premium, due to shares being less liquid than publicly traded equity. Life-cycles typically range from three to seven years.

Real estate: A collective investment scheme with a portfolio consisting mainly of direct property along with other property-related interests. Most common forms include unit trusts, open-ended investment companies and limited partnerships. Real-estate funds take a number of different legal structures depending on their domicile and target customer.

Traditional active

Open Ended Investment Company (OEIC): Pooled, collective investment schemes, often with umbrella fund structures in place. OEICs differ to unit trusts in that they have a depository rather than trustee in place and are constituted as limited companies.

Unit trusts: Classed as collective investments, where funds are pooled together and invested in a portfolio of companies and asset classes, as determined by the fund manager. The aim is to leverage the fund manager's primary research capabilities and market knowledge. Investments may include equities, gilts, commodities and commercial property.

Footnotes

1 Based on custom global indices of mutual funds and ETFs, Deloitte analysis, 2010.

2 Source: Blackrock ETF Landscape Industry Review, Blackrock, Year End 2009.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.