PAYING DIVIDENDS?

For many charities, maintaining and increasing income is a constant challenge. In this article, we explore one of the main sources of investment income – the dividend.

An investment portfolio has often been the asset base from which to generate current income and provide for the future. In the quest for yield, it is important to review the security of that income stream and the factors that threaten it on a regular basis.

The stock market has traditionally been an excellent long-term store of value, protecting investors from inflation. A healthy balance sheet and rising earnings should support a progressive dividend policy. Put simply, the dividend can be regarded as a vote of confidence from the directors of a quoted plc as to the financial strength of the business.

Short-term movements in the stock market do not always reflect healthy trading and rising dividends. But a consistent increase in earnings and dividends suggests that capital values will rise over the long term.

FTSE 100 Examples

Several of the UK’s leading companies have been very generous towards shareholders recently. Figure 1 highlights examples taken from the latest full financial year results of various companies. The Royal Bank of Scotland and BT have hiked their dividend distributions by a quarter – impressive stuff when you consider that’s eight to ten times the rate of inflation!

So far so good, but can it really be that straightforward? Well, not exactly. Take BP and HSBC, for example. These are two of the largest UK plcs and it is quite likely that they feature in many charity investment portfolios. Together, they represent 13.7% of the FTSE 100 and almost one fifth of the total dividend income of the FTSE. In its financial year ending December 2006, BP increased the dividend by 10.1% on the previous year. HSBC pushed its dividend up by 11%. However, both now report earnings and declare dividends in US dollars which, when translated into sterling, means UK investors have actually received little more than in the previous year.

The two highest-yielding stocks in the FTSE 100 are United Utilities and Lloyds TSB. The former, as a regulated business, has, for many years, distributed virtually all of its earnings in the form of dividends, and the pay-out has risen in line with inflation. Lloyds TSB, on the other hand, has just announced its first dividend increase in five years. Holders of Lloyds TSB shares throughout this time will have seen the spending power of this income eroded by inflation. The ill-timed acquisition of Scottish Widows meant profits from the banking arm were diverted to prop up the life and pensions business. Despite considerable pressure from the City in 2003 to cut the dividend, management dipped into reserves. They have since rebuilt dividend cover to a level at which they can now increase the payment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fig 1: Dividend increases reported in each company’s latest full financial year results.

The early part of this decade was tough for many businesses, and while Lloyds TSB held the dividend, many blue chips were forced to slash theirs. Scottish & Newcastle, Aviva, Royal & Sun Alliance and BT all spring to mind. All of these businesses are now operating a progressive dividend policy again. Many charities found that their investment income had frozen or even dropped, not just due to market conditions, but because gilt yields were low and transitional relief was phasing out the tax credit that charities could previously reclaim.

What Does The Future Hold?

The dividend yield on the UK stock market is about 3.1% at the moment, although charity portfolios are likely to have a bias towards the higher yielders. Dividend growth has been very healthy recently, as shown by Figure 1. But with economic growth in the western world threatened by a tail off in consumer spending, and less willingness by the banks to lend, it is realistic to expect dividend growth to slow too. There may be a few shocks, and recent events suggest that superior dividend growth in the banking sector may be over for now. Charity trustees should ensure that their investment portfolios are well diversified to weather any storms ahead.

"There may be a few shocks, and recent events suggest that superior dividend growth in the banking sector may be over for now"

GIVING A SHARE IS GOOD

Tax Reliefs

The income tax advantages from making cash donations to UK charities under the Gift Aid scheme are widely known. Less well known are the more generous lifetime tax reliefs available on the gift of certain assets to UK charities.

A gift of an asset to charity, either outright or at a price less than its cost, is treated as disposed of at no gain/no loss. The donor therefore obtains full capital gains tax (CGT) relief on any inherent gain.

Income Tax Relief

Since April 2000, there has also been income tax relief available on the gift of ‘qualifying investments’ to a charity. They include:

- quoted shares or securities

- units in an authorised unit trust

- shares in UK open-ended investment company (OEIC)

- interest in an offshore fund

- a ‘qualifying interest in land’ from April 2002.

With this relief the donor gets an income tax or corporation tax deduction for the net benefit to the charity (normally the market value) of the qualifying investment, plus incidental expenses of the transfer, less any consideration or benefit received by the donor. This relief is in addition to the CGT relief and means it can be significantly more beneficial for the donor to give shares rather than sell the shares and donate the proceeds.

The tax relief is claimed via the tax return for the year in which the gift is made. Those in employment, or receipt of a pension, can ask for their Pay As You Earn tax coding to be adjusted during the tax year of the gift, so receiving the benefit of the tax relief earlier.

It should be noted that the income tax relief on gifts of qualifying investments is given as a deduction against income. In order to obtain maximum relief, an individual should not give away shares worth in excess of income otherwise taxable at 40%.

Although larger charities often have a department to assist with processing of such gifts, not all charities can receive shares and some might not accept shares in particular companies for ethical reasons. If the charity cannot receive the shares, for whatever reason, it may be possible for them to be sold on behalf of the charity in order to maximise tax relief. Professional advice is recommended in such cases.

Inheritance Tax Exempt

Gifts to charity are broadly exempt from inheritance tax regardless of whether the gift is made during the donor’s lifetime or as a legacy in a will. If an intended donation can be made during one’s lifetime without causing concern over the loss of capital/income, then doing so can be more tax efficient and possibly more rewarding. It is important to update the will if the lifetime gift is intended to replace the one in the will.

|

The example in the box below highlights the difference between the gift of the sale proceeds and that of the qualifying asset itself. Say Mary is a higher-rate tax payer who wishes to make a charitable donation using £100,000 worth of shares. It has been assumed that they have an inherent CGT liability of £12,000. If we say the net value of Mary’s shares is £88,000 (their value less the inherent CGT liability), her net cost in giving the shares becomes £48,000. The charity is, however, worse off as it does not obtain a basic-rate tax ‘refund’ on receipt of the shares. Mary might be minded to use part of her saving to make an additional donation. The changes proposed for CGT in the 2007 Pre-Budget Report will have an impact on the inherent CGT liability, but not affect the underlying basis of the relief or the calculations. |

|

|

£ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CAUGHT IN THE ACT

The impact of the Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005.

The Charities and Trustee Investment (Scotland) Act 2005, (the Act) has inevitably raised a number of unexpected issues, with some unintended consequences. While few have been surprised by the July 2007 ruling by the Office of the Scottish Charity Regulator (OSCR) that the High School of Dundee should keep its charitable status, the Act has created some issues that were not anticipated during the consultation process.

Trustee Remuneration

Section 67 of the Act clearly states that the majority of trustees should remain unpaid. But realisation has only just dawned that many Scottish trustees could breach this principle. If the trust settlor has appointed the solicitor that drafted the trust deed and administers the trust as a trustee, as well as the investment manager that advises on the investments, in an indirect way, these two trustees could be seen to be being paid. If the only other trustee is the settlor, then the unpaid trustee will be in the minority. The obvious solution would be to appoint more trustees – if they can be found.

Trustee Indemnity Insurance

Section 68 of the Act goes on to define remuneration as including benefits in kind. This means that trusts which provide all of their trustees with indemnity insurance could fall foul of the new law. OSCR has been aware of this issue since May 2006 and is working with the Scottish Executive to find a solution. This will probably require an amendment to the provisions of the Act. In the meantime, OSCR is unlikely to take enforcement action against a charity that continues to offer indemnity insurance.

Defining ‘charity’ and ‘charitable Purposes’

In order to pass the new charity test, a charity must not allow its property to be used for non-charitable purposes. Quoting from OSCR’s briefing note (3/8/07) on the use of the terms ‘charitable’ and ‘charitable purposes’ in constitutions, Section 7(4)(a) of the 2005 Act says that a body cannot meet the charity test if: "Its constitution allows it to distribute or otherwise apply any of its property (on being wound up or at any other time) for a purpose which is not a charitable purpose." There is no requirement to include a clause defining the meaning of ‘charitable’ or ‘charitable purpose’ in the constitution of a Scottish charity, and where this has been done, OSCR now needs to ensure that these terms are consistent with the 2005 Act. It is possible that definitions that are charitable under tax (and English) law are not considered charitable under the 2005 Act.

Where a charity has a constitution that contravenes this provision, or has an established practice that contravenes this provision, OSCR will normally issue a written direction ordering the matter to be resolved. In such cases, it is expected that charities will be given one year to comply.

Other Issues

These are just a few of the issues that have arisen since publication of the Act. If you are aware of others that have had an impact, particularly concerning the appointment of trustees or the management of investments for charitable purposes, then we would be pleased to hear from you.

NEW INVESTMENT TECHNIQUES

Article by Colin McLeanColin McLean, managing director of SVM Asset Management Ltd, explains how charity trustees can take advantage of changing investment techniques.

New investment techniques rarely get much attention from charity trustees. Stewardship of charity assets is focused on long-term strategy, protection of capital and prudence. Many feel that traditional investment approaches have served the sector well. Yet the investment landscape is changing, with new potential for efficient portfolio management within unit trusts, OEICs and Undertakings for Collective Investments in Transferable Securities (UCITS). Trustees need to understand this new world and the potential risks of what they thought were conventional funds.

Few charities have been attracted to hedge funds, despite some high-profile investors such as the Wellcome Trust. But many other conventional funds can now use hedging techniques and, increasingly, the line between conventional funds and alternative assets is becoming blurred. In particular, the new UCITS III regulations allow UCITS funds to use a wider range of instruments in an attempt to enhance returns, mitigate risks or reduce costs. Investment trusts have been able to do this for some time, with an increasing number taking advantage of the flexibility. This ranges from trying to neutralise currency exposure in, say, a global investment trust, to writing options to gain income, or trying to reduce the potential impact of a stock market fall. Charities may not want to use these techniques and instruments, but will find that many pooled funds they own are using the new freedoms.

In the US, many endowments and charities have invested in the new areas. One popular type of fund, called 130/30, sits somewhere between conventional and hedge funds. It combines a geared, traditional, long-only portfolio with some hedging. In effect, clients get a high conviction portfolio exposed to stock markets. But there is also the potential for a little more stock-picking alpha from some additional longs and shorts. This approach has already attracted an estimated $50bn in assets in North America, with pension funds being the first buyers of the strategy. It provides a step towards accessing additional manager stock-picking skill, but typically with more limited risk than hedge funds. Fees also tend to be nearer those typical of conventional funds. UK pension consultants are already showing interest in the concept, and there is talk of new fund launches.

However, the potential for active risk management and additional manager skill already exists in conventional investment trusts. Provided hedging positions reflect genuine risk management, there is a wide range of instruments available to fund managers. Indeed, global generalist trusts have used currency hedging on many occasions over the past two decades, and several trusts also create additional revenue by writing options against the core portfolio. Of course, investment trusts have always had the ability to borrow, and to gear up a fund to, say, 20% according to stock-market conditions, is used by many.

Trustees buying a fund that is using these techniques will need to be sure of the manager’s experience and the controls applied by its risk-management team. The strategy should be explained to investors. It is not a licence to create a trading fund, but permission for a specific level of additional stock-picking. This may be closer to a manager’s skills than market timing, but will also give a fund the opportunity to go significantly below full market exposure in a downturn.

Investment trusts that have taken advantage of a wider range of securities should get more attention. They provide an attractive entry point for those who want their favourite managers to have a broader range of tools available in order to deal with a change in market conditions. Already, the flexibility that gearing and hedging offers has helped some with performance and risk management. More widespread use of these techniques in the investment trust industry could offer real competition for UCITS IIIand hedge funds. Charities should understand the whole range of efficient portfolio techniques now available.

INVESTING IN COMMERCIAL PROPERTY FOR CHARITIES

Article by Rod RossRod Ross is a director of Goodman Property Investors, one of the UK’s largest property fund managers. Rod Ross outlines how charities can benefit by investing in the commercial property sector.

The commercial property sector has had three years of exceptional returns averaging 18.7% per annum. These returns have been driven largely by increased investor appetite for the asset class and, in no small part, freely available debt finance. However, it appears the bull run is now over and more modest returns lie ahead.

At this stage in the market cycle a number of questions may be asked.

- Why invest now?

- Are future returns attractive?

- What advantages does property as an asset class offer to charity investors?

Income And Capital Returns

A distinguishing feature of property investments is rental income. This is generally fixed on a contractual basis and paid in advance at regular intervals, usually quarterly. Returns from property investments therefore have two components:

- Income

- Capital growth

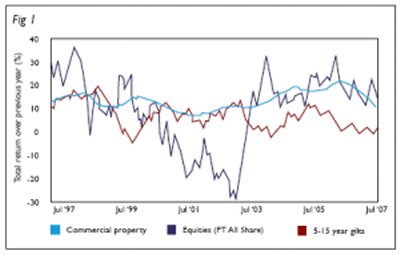

While in periods of high performance capital growth will comprise the major component of returns, it is the income element which differentiates property as an asset class and defines the way returns respond to an unsettled environment. Property returns tend to be significantly less volatile than those of either equities or gilts, as illustrated in Figure 1.

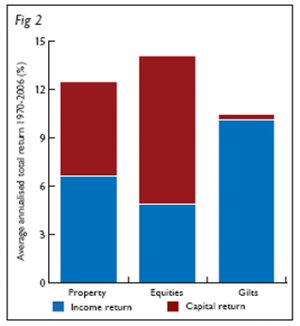

Although the strength of the income stream from a property asset depends on the tenant’s ability to pay the rent, the contractual aspect of the rental income provides a bond-type characteristic. Indeed, properties let on very long leases to the Government or, for example, to FTSE 100 companies may, on occasion, be priced quite closely to equivalent redemption-dated bonds. Property investments also have the potential to provide capital growth and, consequently, can be regarded as a type of equity/bond hybrid, with returns expected to lie between the two, as shown in Figure 2.

SDLT Exempt

Property transactions in the UK incur Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) and most commercial property investments will fall within the top band of 4%. Charities and certain specific pooled fund structures available only to charities are exempt from SDLT. On a typical property acquisition, the benefit to a charity is an additional income return of around 0.2%, giving a unique advantage.

Portfolio Diversification

A further benefit of property in an investment portfolio is the low correlation of returns compared to other major asset classes. Over the past 35 years the correlation between property and the stock market has been one third of the correlation between equities and gilts. Property can therefore be considered to have a strong diversifying effect within a portfolio.

At a time when income returns from investments are generally scarce, volatile, or, at worst, both, commercial property provides a reliable, predictable and growing income stream. Property leases typically have provision for the rent to be reviewed at predetermined intervals, usually three or five years. In the UK, these reviews are conventionally upwards only, effectively giving a ratchet effect to the investor’s income stream. The potential for rental income growth is therefore another factor unique to property, which is of particular attraction to an investor requiring an effectively inflation-proof income stream. Rental growth will also flow through into capital values and give a further boost to total returns.

Perhaps the most important distinguishing characteristic of property, compared with other investment assets, is the non-homogenous nature of the investments; every asset is unique and different. While this can prove problematic for a small investor wishing to ‘buy the market’, for large investors it provides not only a further level of diversification, but also potential to add value to the portfolio.

Active management of individual assets is a further opportunity for investors in property, which can provide an additional level of both income and capital returns. The portfolio manager should be acutely aware of differences between individual properties in each location and seek to maximise any advantage which can be gained from this. Asset management can take a wide variety of forms.

It might involve:

- widening a planning consent to allow a greater variety of more valuable uses

- upgrading, refurbishing or extending a property, discussing tenants’ requirements with them and negotiating changes to the leasing structure to increase the overall rent payable (perhaps most frequently).

Timing

Timing of management initiatives can be critical. To achieve a re-letting of a unit shortly before rent reviews fall due elsewhere within the property can create evidence allowing rent to be taken to a new level, far outstripping underlying levels of market rental growth. At the current point in the market cycle, successful management initiatives can provide a significant boost to overall returns. Choosing the best portfolio manager is therefore essential for gaining the optimum return from property.

Disadvantages of commercial property are the ‘lumpy’ size of individual investments and the time taken to achieve transactions. Due to the relatively large individual lot sizes of investments, it is difficult for small investors to build a portfolio which benefits from sufficient diversification to allow asset-specific risks to be managed. For these reasons, investors may well be advised to seek an appropriate investment fund by which they can pool their resources with other investors to achieve a more attractive critical mass and sufficient diversification.

Maximising Benefits

By carefully selecting a manager, the investor can also hope to maximise the benefits of a programme of active asset management. Unfortunately, despite the plethora of available funds, both openended and closed-ended, investing in commercial property, very few either have charitable status or are reserved exclusively for charity investors. Without benefiting from their SDLT exemption, investors will lose a valuable additional boost to their income. However, choosing a fund for its charitable status alone may not provide the additional management boost which maximises the benefits of the asset class.

At a time when many charities are seeking to extract ever-greater income from their investments, the income return from property is higher and more stable than from other asset classes. It is also capable of being proactively managed to create extra returns. A carefully selected portfolio can provide an attractive level of income with potential for capital growth, while retaining a diversified spread of asset types. The years of plenty may be over for commercial property for the moment but for many, the attractions of a predictable, growing income stream, supplemented by skilful management, will provide an attractive addition to a portfolio.

PRIDE AND PREJUDICE

Article by Susan DiamondIt is a truth universally acknowledged, that a person in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a charity…

Susan Diamond, head of fundraising for the National Galleries of Scotland, explains how both charities and donors can benefit from tax breaks on donations.

In the US, philanthropists have never been afraid of giving or talking about charitable donations – think Bill Gates and Warren Buffet. In the UK, donors are usually far more reticent, afraid that it appears like showing off. But times are changing and more high-profile donors have started talking about their giving. It seems it is not just to raise their profile but to encourage others to do the same. Tom Hunter’s pledge to give £1bn to charitable causes over his lifetime is a recent example.

Scotland is blessed with one of the finest national art collections in the world – unquestionably something to be proud of and enjoy. We not only acquire and care for these treasures on behalf of the nation, but also ensure that they are available to as many people to enjoy and engage with as possible.

The National Galleries of Scotland relies on donations and legacies to enhance this excellent work. We want to do more in the areas of education, conservation, acquisition of works and exhibitions. The permanent collections are free to all and we would love more people to enjoy the collections, either by visiting in person or online. Our talks, lectures and courses are either free or subsidised, thanks to our donors.

The truth is that you don’t have to be a billionaire to help good causes, and the best news is that there are some tax-efficient ways to do it.

Gift Aid has provided a real boost to charities since its inception in the 2000 Budget. It has proved very popular with both donors and charities, as it increases the value of individual gifts at no extra expense to the donor, and claws back money from the tax man. Gift Aid allows a charity to claim back the basic-rate tax paid by the donor, amounting to just over 28p for every £1 given. It is even cheaper for higher-rate tax payers to give, as they can personally claim back the additional 18% on their grossed-up gift.

If you are a higher-rate tax payer you should reclaim the additional tax relief on your donations over the year, not only to deprive the Chancellor, but also to encourage you to donate your rebate back to the charity of your choice. It is now possible to donate all or part of your tax rebate to charity on your self-assessment form and add Gift Aid. All you need to do is add the relevant charity code to the form and HM Revenue & Customs will do the rest. You can remain anonymous if you wish. For example, the National Galleries of Scotland’s code is NAC11EG.

Changes in the 2000 Budget introduced tax benefits for the gift of land or buildings, shares and securities to charities. Under this scheme, a donor can claim relief on the market value of the qualifying investment at the date of the transfer, plus any incidental costs (for example, brokers’ fees or legal fees). This is particularly useful for shares with a large capital gain because the disposal to a charity does not incur any charge to CGT. The value at the date of transfer (not the book value) and costs are then deducted from the donor’s income calculations at the end of the year.

Smith & Williamson works with the National Galleries of Scotland to make sure that both we and our donors benefit fully from this way of giving.

For further information on any part of our work, or to support us by becoming a Friend of the National Galleries of Scotland, please get in contact.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.