Article by Simon Lamb and Philip Shephard, PricewaterhouseCoopers

Over the last couple of years, major communications companies have rationalized their portfolios, strengthened the ownership of their separate operations, and increased their footprint overseas. In the United States, in particular, there has been a substantial round of domestic consolidation, including mega deals such as the US$39 billion acquisition of Nextel by Sprint and the $73 billion acquisition of BellSouth by AT&T. In Europe, the volume of communications deals in 2005 and 2006 remained stable, with 447 and 422 transactions, respectively.

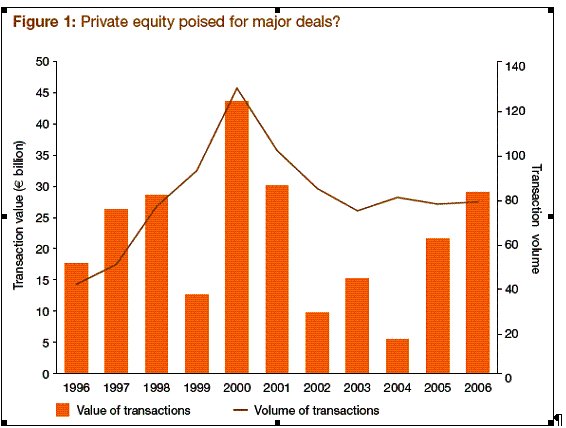

Those figures fall short of the volume at the market peak in 2000, when nearly 900 transactions involving European businesses were recorded. But deal values in Europe have seen a strong recovery, hitting more than €100 billion in both 2005 and 2006 compared with a low of €36 billion in 2004. In 2005, substantial individual deals included the €6 billion-plus acquisitions of Wind in Italy and Amena in Spain. In 2006, the landmark transactions included the €25 billion acquisition of O2 by Telefónica and the €8.5 billion acquisition of TDC by a consortium of private equity investors. Other major non-European deals included Softbank’s purchase of Vodafone KK in Japan for $14 billion.

What’s driving the deals?

This resurgence in value of global communications deals over the last couple of years has been characterized by three factors: fixed-mobile convergence, consolidation, and international expansion. As major communications companies have seen their balance sheets restored to relative health through disposals and increasing profitability, they have been able to undertake some significant transactions to position themselves to execute convergence strategies, providing users with not only fixed and mobile services, but access to a range of high-speed data and content as well.

Fixed-mobile convergence

Fixed-mobile convergence has been around for a while, at least as a concept, and what’s shaping it has evolved during the last two years. In many markets, the growth of wireless revenues has slipped to single figures. Fixed-line voice revenues are falling for many operators while broadband penetration is accelerating. Operators, therefore, are looking at opportunities beyond their core markets, trying to build complementary businesses that capture a greater share of increasing consumer spending on communications, media, and entertainment, blurring the traditional divide between these markets.

At the beginning of the decade, the much-vaunted idea of fixed-mobile convergence failed to deliver the value that was widely discussed and hoped for by many. Mobile operators, for example, saw far greater value in focusing on their core markets—which were still showing high rates of growth—than they did in offering new services. But with many of those same mobile markets reaching saturation, is convergence more likely to deliver on its promise in today’s market? A number of factors suggest that pursuing convergence will yield a considerable prize to the successful.

For instance, in the more developed markets of Western Europe and the US, operators are being hit by a number of factors that are intensifying competition. High levels of mobile penetration have reduced the scope for growth from traditional voice services, and data services have yet to have a meaningful impact. At the same time, fixed-mobile substitution has begun to bite hard, causing declines in fixed voice revenues while the growth of broadband encouraged by LLU (local loop unbundling) has opened up the further threat of VoIP (voice over Internet Protocol). Smaller single-service players in those markets are finding life increasingly tough.

As national incumbents set about positioning themselves for convergence, the last two years have seen a number of deals involving the reacquisition of assets that were disposed of only a few years prior.

France Telecom completed its buyout of minority shareholders in mobile operator Orange in 2005. Telecom Italia followed suit with its buy-back of the outstanding 44% of Telecom Italia Mobile (TIM) for €23 billion. Deutsche Telekom completed the acquisition of outstanding shares in ISP T-Online that it spun off in 2000. In similar consolidation in the Irish market, incumbent Eircom re-entered the mobile market with its acquisition of Meteor for €420 million, and Belgacom bought out Vodafone’s 25% stake in Belgacom Mobile for €2 billion.

This reversal of the trend to divest assets is a response to the decline in revenues for fixed services and the perceived importance of capturing a customer base that increasingly seeks to use one provider for all its communication needs. In the US, Verizon bought MCI for $8.8 billion and AT&T got back into the mobile business through its full ownership of Cingular following the BellSouth acquisition. Having control of fixed, wireless, and broadband networks looks to be a major priority, as tripleand quad-play converged services are designed and rolled out to consumers.

While many of the transactions of the last couple of years can be understood in terms of pursuing a converged strategy or responding to the perceived opportunities that convergence creates, most are at the preparatory stage. There is a sense of expectation in the market, but also a degree of anxiety, about the extent to which convergence will deliver on its promises this time around. In that context, the €1.3 billion tie-up between NTL/Telewest (now Virgin Media) and Virgin Mobile in the United Kingdom to offer quad-play services will be watched carefully by the industry, and the very public spat between BSkyB and Virgin Media over content will be followed closely. Other deals with a distinctly convergent flavor, such as Sky’s acquisition of Easynet and CarphoneWarehouse’s acquisition of AOL UK for €548 million, are of great interest strategically but of low value comparatively.

There are also signs that competition may arise from other sectors. They include, for example, eBay’s acquisition of Skype and Apple’s launch of the iPhone in June—the first handset with the potential and the marketing impact to drive consumers much more rapidly toward convergence. Taken together, then, the signs indicate that 2007 may be the year when the promise of convergence is asked to deliver.

Consolidation

Creating scale through in-country consolidation has been at the heart of several other headline deals of the last couple of years. In 2005, 23% of European deals by value were classed as consolidation, although this percentage dropped in 2006, with 13% representing some form of in-country acquisition. In the US, consolidation represented the majority of the deal value over the same period.

As markets mature, consolidation will increase when smaller operators find themselves unable to compete. Most markets will leave room for only two or three major players. Consolidation will occur particularly as we move into next generation networks and services that will require significant investment. The US market, as mentioned already, has consolidated significantly to three main players. Europe, with a similar sized population, still has at least two main operators per country.

In mobile, recognition is widespread that in terms of market share, the fourth—and in some cases third—place operators will struggle to compete in national markets. Indicating this tougher environment, Nextel and Sprint came together in a deal valued at $37 billion, TeliaSonera acquired Orange Denmark from France Telecom for €600 million to consolidate with its existing operation in Denmark, and T-Mobile in Austria bought mobile operator tele.ring for €1.3 billion. In the Netherlands, KPN sought to bolster its mobile business with the €1 billion acquisition of Telfort, the ex-O2 Netherlands business, and in Greece, TIM Hellas merged with its smaller competitor Q-Tel to create a mobile business with a subscriber base in excess of three million.

Against a background of declining income for fixed calls, the alternative providers look to be acquiring scale in order to square up against the incumbents with converged offers.

In the UK, Cable & Wireless acquired Energis with the express intention of ensuring that it had the scale to compete with incumbent British Telecom (BT) to provide high-speed converged services. In a similar move across the channel, Vivendi Universal’s subsidiary Cegetel merged with Neuf Telecom to create the second largest fixed-line operator in France and a major player for high-speed Internet services. The acquisition of altnet Invitel in Hungary by cable company HTCC typifies the types of transactions that are seeing smaller providers combining to take on incumbents both in their home markets and regionally.

European cable operators also have pursued consolidation in their efforts to compete with incumbents. ONO, one of Spain’s leading cable operators, acquired 100% of Auna TLC, the cable division of Grupo Auna, for €2.2 billion, and Liberty Global acquired NTL Ireland. In the UK, in the largest European cable deal of the last two years, NTL acquired Telewest for €4.75 billion, creating the biggest single cable operator in the UK.

Private equity has played a significant role in the European cable market. Cinven, a major player in the cable space, has completed acquisitions in France: Altice One (which also includes Video Com and which serves the Alsace region); Coditel (which provides telephone, broadband, and digital TV to subscribers in Belgium and Luxembourg); as well as the cable operating subsidiaries of France Telecom and Canal+ and the Dutch cable operator Casema (in a deal that brought together Casema—the third largest cable provider in the Netherlands—with Multikabel, the fourth largest). North America also has been an active market for financial investors, with the $25 million acquisition of Alltel by Texas Pacific Group and GS Capital Partners and the proposed $45 billion sale of BCE in Canada to a consortium of private equity firms.

International expansion

The last major boom in operators’ corporate activity in 2000 included the execution of deals designed to achieve truly global businesses operating across all major markets. Today, we are seeing a more selective international strategy being pursued by some of those businesses that previously sought to bestride the world. With developed markets showing signs of saturation and revenues under pressure from intense competition, operators are turning their attention to fast-growing markets that have penetration rates significantly lower than those of Western Europe.

Vodafone, for example, has made significant disposals in Japan, Belgium, Sweden, and Switzerland. Rather than competing against established players in all markets, Vodafone appears to be consolidating its position in the markets in which it has a leading operation and focusing on other markets that suggest significant growth opportunities. These consolidations include acquisitions in Turkey, where it bought mobile operator Telsim for €3.6 billion, as well as acquisitions in Central and Eastern Europe, among them Mobifon in Romania and Oskar Mobil in the Czech Republic for €3.5 billion. Completing the deal to buy a majority stake of Hutchison Essar in India for €11 billion will transform Vodafone’s growth profile.

In addition to making the largest European acquisition of 2005 and 2006 (the €25 billion paid for O2), Spain’s Telefónica has also expanded into Eastern Europe with the acquisition of Cesky Telecom from the Czech government for €2.8 billion. Others, too, have joined the race into the highpotential markets in Eastern Europe, with Swisscom’s acquisition of Antenna Hungaria, Telekom Austria’s acquisition of Mobitel in Bulgaria, and Telenor’s buying of Mobi63 in Serbia. Completion of the sales processes of the Bulgarian Telecoms Company and GTS are imminent at the time of writing.

A trend in the European region has been the expansion of the Middle Eastern operators. Egyptian operator Orascom acquired Wind in Italy for €10.3 billion and, recently, TIM Hellas in Greece, while Oger Telecom spent $6.5 billion on Turk Telekom. Noticeable by their absence from international deals have been the US operators, who have focused mainly on domestic consolidation.

Despite the constant speculation about private equity in most transaction processes, the actual amount successfully concluded is still relatively small, although growing. In 2005 and 2006, private equity accounted for 17% of deals by volume in the European market. However, at more than €30 billion in 2006, they accounted for nearly 30% of value— significantly higher than in the previous five years (which ranged from 15% to 20%). In the biggest single private equity deal, the Danish incumbent TDC was acquired for €8.5 billion by a consortium comprising KKR, Blackstone, Apax Partners, Permira, and Providence Equity Partners. One member of that consortium, Blackstone, also acquired a stake in Deutsche Telekom for €2.65 billion.

After European telecommunications transactions peaked in 2000, investors began turning some attention to fast-growing markets in other parts of the world; however, the fact that private equity investments accounted for more than 30% of the deal value in 2006 may indicate a new trend.

Source: Thomson Financial, deals where the target was in wireless, telecommunications services, telecommunications equipment, space and satellites, other telecom, cable networks (not channel management), in Europe (Western and CEE) and the "Acquirer Macro Description" was "Financial" between January 1,1996, and December 30, 2006, with the NTC acquisition included.

As noted earlier, private equity plays have been particularly active in cable, but interest has also been significant in other communications assets. Infrastructure has attracted particular attention, as demonstrated by the €5.1 billion investment by Texas Pacific Group and AXA Private Equity in French mobile tower and digital broadcast group TDF, announced in October 2006 (and expected to be completed in 2007).

Some private equity industry commentators have predicted a private equity deal in excess of $100 billion within the next two years. Communications assets, including even some of the larger national incumbents, have been discussed as possible targets for such a transaction. Though some barriers to such a deal taking place exist— including regulatory obstacles—there seems to be little doubt that the disciplined and value-focused approach that private equity brings to the market will continue to exert a strong influence. Add to that the growing willingness of private equity houses to work together (as shown in the TDC and BCE acquisitions) and the limits to what can be achieved in the communications sector appear to be few.

Avoiding earlier mistakes

The substantial deal activity in 2001 and 2002, followed by the stock market falls and resulting liquidity crunch, left a number of operators in a difficult financial position. Operators need to learn from this experience to ensure that the current M&A activity does not lead, ultimately, to disappointed shareholders. We believe that a revised approach to acquisition is evident in recent M&A activity, showing that indeed a number of lessons have been learned. Those seeking to acquire are now focusing their deals more on strategic fundamentals, formulating clearer rationales, and more rigorously assessing and mitigating risks associated with deals. The market for communications businesses is very competitive, with both trade and private equity players seeking to obtain assets that now represent long-term, cash generating machines.

To win in auctions, players often need an edge in terms of insights that will enable them to unlock hidden value post-acquisition. Many recent deals have been done at relatively high prices, creating pressure to rapidly implement integration benefits. What creates value in most deals is cost savings, be they in marketing, customer services, networks and operations, or central overhead. Executing such programs is fraught with difficulty and risk, and acquirers will need to invest in the robust methods that can deliver sustainable change while balancing the requirements of "business as usual" value creation.

Investment and change programs that are unbalanced can result in severe consequences, for example:

- Making changes that are not sustainable and that cause customers to perceive degradation to the level of service they receive.

- Eliminating redundancies followed by re-recruitment, often disguised as taking on former personnel as contractors.

- Failing to realize the full value of synergies, often due to former management teams remaining in situ for years beyond the original intention.

- Failing to realize expected improvements in earnings from existing performance improvement projects—both revenue and cost related—as a result of not focusing on business as usual.

Another area that companies need to consider after a deal is local context. Communications operations typically serve the needs of local customers and thus have a primarily national focus. There are some genuinely international services—for example, mobile roaming or networking solutions for major multinational organizations—but they tend to be served from operations built on national units. Thus, while there are benefits from international scale (in procurement and R&D), operators need to be very sensitive to local market dynamics. A model that works in one geography or culture often is incompatible in another.

Many acquisitions also have value associated with the competencies of acquired management and other personnel, and nearly all place pressure on management to deliver. Post-merger work that is insensitive to the needs of personnel can result in the loss of valuable people, as well as suboptimal performance in the resulting integrated operation.

We believe that all acquirers can benefit from adopting best practices that have been road tested by leading private equity houses. For such players, debt funding of deals depends on developing bankable business plans and ensuring that financial, commercial, operational, synergistic, and separation aspects behind the projections can withstand the scrutiny of an independent diligence process. This protects equity holders, by helping to control the risk of private equity management being too optimistic in valuations, as well as debt holders. As a consequence, the planned cost savings and synergies from integration are normally well founded.

Operators and investors must remember the failed integrations of recent memory— the synergies not realized five years on, the acquired company that vanished through customer and staff defection, the billing project that caused national headlines, the separation costs and issues that resulted in budgets being missed—and translate the carefully prepared pre-acquisition plans into a powerful, closely managed program of work. All of that needs to be supported by a well-mobilized team of managers, from both the acquiring and the acquired businesses, and clear ownership of every aspect of the integration. Those steps, and the funding behind them, must not be underestimated if investors and operators want to drive full benefits from the deals and meet shareholders’ expectations.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.