Sound advice

This is the second report in the ‘Sound advice’ series from the Consulting practice at Deloitte – the other two being:

Cutting costs

More a frame of mind, less a special event

Companies are undertaking cost reduction programmes at an unprecedented rate and on an ever larger scale. More than three-quarters of the FTSE 100 companies have started such a programme in the past 12 months, and almost all of those involved in them say they have been a success. But if that is really so, why do they keep on repeating them... again and again and again?

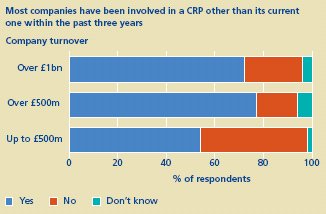

A recent survey commissioned by Deloitte found that more than half of a sample of large British companies had carried out three or more cost reduction programmes (CRPs) in the past three years. More than a quarter of the companies in the survey had carried out five or more CRPs over the three-year period. The same intensity of cost-cutting was found among very large companies as among smaller ones.

Almost three-quarters of the large companies in the survey with turn-over in excess of £1 billion, indicated that they expect their current CRP to last for more than a year. This amounts to an almost continuous process of rolling out new measures to cut costs. This activity is hugely disruptive, making exceptional demands on resources and dangerously undermining morale. Almost the first thing that employees think when they hear about a new programme is, "Will this be the one that finally eliminates my job?" Surely there is a better way to achieve greater efficiency and competitive advantage?

Entrenched attitudes

Most companies say they initiate CRPs because their profits and profitability are below expectations. "There was a general shift in technology," said one telecoms company executive in the survey, "and we experienced a reduction in revenue, but without a reduction in costs." Another significant spur to cost cutting is mergers and acquisitions, particularly among larger companies. As M&A has increased, so have CRPs designed to capture the synergies on which many of the deals are based.

Neither of these circumstances (profits below expectations or mergers and acquisitions) is exceptional for large companies today. A lot of corporate functions remain extremely inefficient, and in many parts of the world M&A activity is running at all-time record levels, spurred by the growth in private equity and the never-ending search for hidden value. Improving profitability and M&A are almost continually on top management’s agenda. So, inevitably, are the cost-cutting programmes that go with them.

If cost-cutting is to be so continuous, can it not somehow be embedded in the corporation and its culture so that it does not cause a major disruption every time yet another discrete programme is introduced? We believe that it can, but for that to happen companies must stop thinking of CRP as a ‘quick and dirty’ solution to a short-term problem. They need to think of cost-cutting as a core capability and entrench it into everyday management attitudes. It should take on some of the elements of the Japanese concept of kaizen, where progress comes through the implementation of a seamless series of small measured improvements, not from sudden irregular shocks to the system.

Industry insight

The study looked at three industrial sectors in particular – consumer goods, financial services and telecoms. In most respects the findings of the survey applied to all three sectors equally. But there were a few differences. Financial service firms, for example, tend to aim higher than the other sectors, setting more ambitious savings targets for their CRPs. Telecoms companies, on the other hand, place more emphasis on cutting purchasing and procurement costs than do companies in the other two sectors. Telecoms companies are also more likely than firms in the other sectors not to set themselves any savings targets at all.

Plant it in the culture

Only one in three companies in our survey said that cost-cutting was embedded in their corporate culture. For too many of them it is still a rough and ready business, carried out in short-lived spurts.

Although many recognise the capacity for cost savings right across their organisations, most of them fail to look widely enough when introducing a new CRP. The most common approach to cost-cutting is by function – IT, finance, operations, etc. Larger firms’ programmes tend to involve more functions than smaller ones. For the sample in our survey, the mean number of functions in larger firms’ programmes was almost six, while for smaller firms it was only 2.3. Fewer than 50% of the smaller firms in our survey said that their current CRP was across the whole firm rather than being confined to specific functions.

Almost half the companies in our sample said that they also cut costs by process. Yet few of them incorporate Activity Based Costing (ABC) to help them discover what is the true cost of each of their processes. Without such basic benchmarking they can never know if their programmes have succeeded.

The fertilisers

For companies to maximise their competitive advantage from cost cutting they need to make their CRPs:

- More strategic;

- More broadly spread across the organisation;

- Professionally benchmarked and monitored;

- Sponsored at the highest level; and

- Incorporating the right incentives and motivation.

Success must always be reflected in staff remuneration packages. Yet very few companies align the aims of their cost-cutting programmes with the incentives and rewards that they offer to the people charged with achieving those aims. Reaching a programme’s targets (or failing to) is rarely integrated into an executive’s bonus scheme. When it is, however, our experience tells us that it works.

"…very few companies align the aims of their cost-cutting programmes with the incentives and rewards that they offer to the people charged with achieving those aims."

How to break free

There are three distinct types of cost-cutting measure. First, there are what we call ‘tactical improvements’, short-term savings that involve little change in systems or organisational design. These include the classic cull of the head count, a method that all too often leaves firms short of resources when business picks up again.

Secondly there are operational savings. These come from streamlining functions, processes or organisational structure. And thirdly there are what we call strategic improvements, those that come from redefining the company’s operating model so that lowcost thinking becomes embedded in it. Many programmes include elements of all three. In our survey, 30% of companies claim that they use all three types of cost-cutting as part of their CRP.

Larger companies tend to pay more attention to strategic options (see chart), but there is still an overheavy dependence on tactical and operational sources of saving. It is our belief that companies must look increasingly to the third option of strategic improvement in order to find sustainable long-term efficiencies.

Vicious cycles

It is easy for firms to get stuck in a cycle of regular cost reduction programmes that make only tactical improvements. To move outside this cycle requires visionary and courageous leadership. For it requires firms to take a leap away from entrenched practices and to think more strategically around their cost base.

In industry after industry, from airlines to banks and telecoms service providers, new upstart rivals have rewritten the rules of competition by establishing new low-cost business models. The incumbent operators have little alternative but to take such a leap and try to regain competitive advantage by radically rethinking their business model. To stick with their familiar cost-cutting cycle is to fiddle while Rome burns.

Other firms find themselves in less dramatic situations. But even they are under pressure to think more strategically about costcutting. Some of the options they should start to examine are:

a) The management of their property portfolio. In our survey of British companies, smaller firms in particular indicated that they rarely target the potential savings that can come, for instance, from sale-and-leaseback deals. Such deals clearly take time. But they can produce sizeable and sustainable savings over the longer term.

b) Further outsourcing. For many firms there are still considerable gains to be made from outsourcing. But again this is not a shortterm solution. Decisions about what should be outsourced and where (onshore or offshore) are strategic and require careful consideration.

c) Their operating environment. This may present unexpected opportunities to cut costs. Environmentally responsible programmes, for example, may provide cheaper options in the longer term – through, say, the greater use of solar power. And the growing use of remote workers, people who no longer need a fixed office base, gives companies an opportunity to rationalise their property portfolio even further. A recent finding that British office workers have far less floor space than they had 20 years ago may merely reflect the fact that for much of the time many of them are no longer there. These days they have other offices – at home, in their cars, or on the premises of their clients – where they do most of their work.

Outsourcing

British companies have been slow to move their operations offshore. Now they are finding that some of the older centres are coming up against limits. If it is not the supply of suitably qualified labour, it may well be the local infrastructure. In parts of India, for instance, the supply of electricity is uncertain, and power failures can increase costs dramatically. Faraway call centres have proved unworkable on occasions. Considerable savings can still be found by moving operations offshore, but firms do need to consider their options more carefully and trawl farther afield for suitable locations.

Measured steps

The effectiveness of any type of cost cutting cannot be determined without proper measurement. Yet one in three companies in our survey said that they set no target for their CRP. For smaller companies the figure was even higher – four out of ten set themselves no target at all. How can they hope to know whether they are successful if they don’t know what they are aiming for? Larger firms tend to set themselves more ambitious cost-cutting targets. The mean target for the largest companies in our survey was 6.4%, whilst 4% of them set the highly ambitious target of 20% and over.

Sometimes a target is refined as a programme progresses. One financial services executive said that his firm’s 10% target "was to apply to the overall cost base. Targets were allocated to all functions. But increasingly the focus turned to the back office/support. Our primary savings were in the retirement packages." Targets which begin as general across-the-board ambitions frequently get refined as the programme progresses.

It is as important for companies to know where they are coming from as to know where they are heading to. Yet about a quarter of the firms in our survey did not establish a financial baseline against which to measure the progress of their CRP.

Some of those which do establish a baseline do it in a haphazard fashion. "We looked at the next three years’ forecasts and found out how much needed to be saved, and worked towards that", said one telecoms executive. Others take a more structured approach: "We looked at the product grouping to see what particular products needed to be improved. We then drew a benchmark against the better performing products to see what needed to be done," said another telecoms executive. Others look outside their own organisation for suitable benchmarks, but often find it difficult to get the right comparative analysis.

Once targets have been achieved it is important to ensure that the achievement is sustained. It is common to cut costs and then have them creep back up again. The results of a CRP need to be carefully monitored after the event to guard against backsliding. One company whose cost savings came mainly from purchasing said that it made sure that its new pricing agreements stayed in place for some time after the programme was over. Backsliding too often forces companies to repeat a cost-cutting exercise shortly after it has just ended.

"One in three companies in our survey said that they set no target for their cost reduction programme."

Get the boss on board

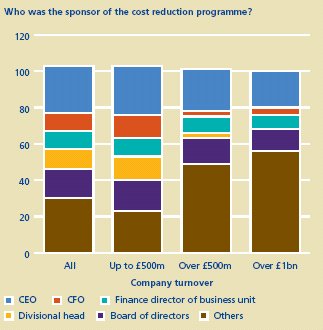

It is absolutely vital for the success of a significant CRP that the CEO is seen to be right behind it. Surprisingly, this seems to be more of an issue for small companies than it is for larger ones. Our survey found that the CEO was the sponsor of more than half the CRPs in businesses with a turnover of more than £1 billion. In companies with a turnover of less than £500 million, he or she was the sponsor in less than a quarter of the cases. This pattern was repeated across all three industrial sectors represented in the survey.

On a day-to-day basis the CEO is less involved. It is his job to keep the cost-cutting exercise on the boardroom agenda. Responsibility for its detailed implementation is most frequently delegated to the division head or to the finance director of the business unit.

It is crucial, however, that the CEO be kept informed of progress on a regular basis. Monthly face-to-face meetings with those responsible for the implementation of the programme (and the delivery of results) are advisable.

The team in charge of the programme should meet at least once a week to review progress and decide on new action to be taken, if any. One telecom company executive said that the keys to a successful CRP are "constant focus by senior management, good communication and strong negotiation."

Too many CRPs rely on part-timers. Half the companies in our survey stated that they use part-time resources for their programmes. Only just over a quarter had a full-time dedicated internal team. More and more companies will have to follow their example. Parttime teams are disbanded when a programme ends. They leave the cuts they have made untended, which allows them too rapidly to fester.

Planning and executing CRPs comes at the acute end of the range of tough tasks that executives have to perform. One financial services executive in the survey described the aim of a CRP as being: "to eliminate costs from the business while not damaging staff morale." A difficult task if ever there was one. If there were an easier way to achieve the same ends most would vote for it. Removing costs from a company’s operations requires courage, endurance and consistency. It is not a task for the faint-hearted.

Send out clear signals

The most frequently cited cause of CRP failure is "lack of buy-in across the business". Success depends critically on the way a programme is presented to both outsiders (such as investment analysts) and to insiders (essentially employees). Yet only a quarter of the companies in our sample communicated news of their CRP externally. Of those that did, shareholders and city analysts were the most likely recipients of the information. Investment analysts are accustomed to meeting with CEOs and CFOs and hearing about their cost-cutting programmes. They can smell insincerity and lack of commitment a mile off. If a company’s share price is not to suffer, they have to be convinced that the cost-cutting is going to work.

So too do employees, on whom the successful implementation of the programme ultimately depends. They are anyway nervous about the implications of CRPs for their own jobs. Larger companies, we found, are more likely to communicate details of their CRPs internally than smaller firms. Of the smaller companies in our survey, less than half give news of their CRP to all staff; for larger companies the figure rises to 85%. Almost a quarter of the smaller companies claim that they say nothing at all internally about their cost-cutting programmes. That is unwise, and it can be expensive.

Multitasking

Cutting costs and searching for growth are too often seen as mutually exclusive activities. For too many firms CRPs are strictly for the bad times, only to be abandoned as soon as times get better and growth begins anew. But companies need to think of costefficiency as a goal for all seasons, not exclusively for winter. The search for efficiency can take place in parallel with the search for growth. The development of new products and markets does not of itself preclude greater cost consciousness in the provision of old ones.

That message must be spread throughout the corporation, and there is no better way to give the right signals than to align rewards with the desired results. One company we know allows its executives to take 50% of all the cost savings for which they are responsible, and to reinvest them in their business. The greater the savings, the greater the potential for growth. Another executive in the financial services industry expressed the intermingling of savings and investment in a slightly different way. The aim of his company’s CRP, he said, was "to invest money in talent so we are able to do more with less staff costs". Multitasking is not just possible for companies; it is essential. To be fully competitive, businesses need to cut costs and go for growth, both at the same time.

"We cut our facilities – I mean less offices. But we did not cut our investment budget."

Conclusion

Companies are undertaking cost reduction programmes at a rapidly accelerating rate. These programmes are highly disruptive and very demanding on resources. Our survey of British companies in three significant sectors – consumer goods, financial services and telecoms – found that more than a quarter of them had carried out five or more CRPs in the previous three years, and a large majority of them expected their current CRPs to last for more than a year. That is an unprecedented intensity of cost-cutting.

The survey also found that companies rely predominantly on operational savings to achieve the targets of their cost reduction programmes. Too many still rely on short-term tactical measures while too few look to longer-term strategic solutions.

Henceforth cost cutting needs to become a part of an organisation’s culture, part of the "way we do things round here". That requires businesses to take a more strategic view of their cost base in order to maximise their competitive advantage, and that is not an easy step to take. The most frequent cause of failure is a lack of courageous leadership.

The six key factors for successful cost reduction

1. Set a clear target and align accountability to it.

2. Senior Executive sponsorship and buy-in.

3. Robust project management approach to drive the programme.

4. Include tactical AND strategic cost saving initiative.

5. Engage and involve the business functions and finance in designing and delivering cost savings.

6. Embed a culture of continuous cost management improvement.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.