Foreword

By John Connolly

Senior Partner & Chief Executive

Deloitte

In this Review, Roger Bootle, Economic Adviser to Deloitte, turns his attention to the UK’s corporate sector. Roger argues that the corporate sector certainly looks in better shape than other parts of the UK economy. But over the next year or two it is still unlikely to provide the economy with quite the spending boost it needs to offset the slowing contributions from households and the government.

He thinks that with firms close to exhausting their spare capacity, they may need to increase their investment and employment if they want to meet any rise in demand. But their inclination to spend their way through the consumer slowdown is likely to be constrained by a slowdown in profits growth and the uncertainties firms face regarding the outlook for demand, the tax regime and the regulatory burden.

As such, Roger believes that the slowdown in consumer spending is set to pull down overall economic growth to around 1.7% this year and 2.0% next year. Consumers are likely to continue to tighten their belts for a while yet, given that unemployment is rising, the housing market is slowing and the prospect of tax rises continues to loom large on households’ horizons.

On a brighter note, although the rise in oil prices could yet push consumer price inflation up further, there are few signs of any second round effects. As such, he believes that the Monetary Policy Committee will be free to cut interest rates to 3.5% by the middle of 2006, helping economic growth to recover to around 2.5% by 2007.

Once again, I hope that this Review helps you in both your immediate and strategic thinking.

Executive Summary

- With consumers and the government no longer able to bear the burden of driving forward economic growth, it is the corporate sector that will come under the spotlight over the next year or two. Firms are able to affect economic growth via their decisions regarding fixed investment, inventories and employment.

- A look back at the past is not exactly encouraging, given that the corporate sector has never provided much of an offset to a weaker consumer sector before.

- But with firms close to exhausting their spare capacity, they will need to increase investment and employment to meet any rise in demand. Although domestic demand is slowing, there are tentative signs of a recovery in the euro-zone, while any falls in the sterling exchange rate could boost UK competitiveness abroad.

- However, there are two important ways in which firms might yet meet any extra demand without spending more money. The first is if an increase in productivity allows firms to raise output without having to hire any extra workers. And the second is if firms choose to run down their stocks, which are currently slightly above normal levels.

- Meanwhile, firms’ ability to spend their way through the consumer slowdown is likely to be constrained by the ability of the corporate sector to finance such spending. Profits growth is set to undergo a cyclical slowdown, exacerbated by competitive pressures continuing to squeeze firms’ pricing power. We expect real profits growth to fall into negative territory before too long.

- At least firms have spent the last few years restructuring their balance sheets, meaning that they are better placed to borrow money than at any time in the last few years. But all of these concerns become immaterial if firms decide they simply do not want to spend more money, due to uncertainty about the prospects for demand, the tax regime or the regulatory burden.

- Overall, then, although the corporate sector certainly looks in better shape than other parts of the economy, enough obstacles remain to prevent it from providing the economy with quite the spending boost it needs given the degree of the slowdown in the rest of the economy.

- Consumers, in particular, will continue to cut back as the economic drivers of household spending remain weak. The stimulatory effect of interest rate cuts will be partly offset by further rises in household debt. Meanwhile, we expect unemployment to rise further, the housing market to keep slowing, and the prospect of tax rises to continue to loom large.

- Overall, we continue to expect GDP growth to slow to around 1.7% this year, before showing only a modest improvement in 2006. Although the rise in oil prices could yet push consumer price inflation up further, there are few signs of any second-round effects. As such, we expect the Monetary Policy Committee to be free to cut interest rates to 3.5% by the middle of next year in order to support real economic activity, helping economic growth to recover to 2.5% by 2007.

Time For A Bit Of PLC

Can a healthy corporate sector offset the consumer slowdown?

The corporate sector has taken a back seat in recent years as the UK economy has been driven forward by the strength of spending by households and the government.

But now household spending growth has slowed and rather than being a temporary blip, it is looking more and more likely that consumer spending will remain soft for a while. With the government having to rein back its spending growth too, in order to get its books back in order, the outlook for the economy hinges crucially on whether companies are ready to take over as the economy’s next big spenders. There are three key issues, namely what companies will do with respect to their fixed investment, their inventories and their employment levels.

As such, in this article, we take a closer look at whether companies have the incentive, means and willingness to spend the money necessary to compensate for the new-found cautiousness of UK consumers.

The corporate contribution in the past

Chart 1 takes a look back over the past 40 years to see whether there have been periods before when the corporate sector has managed to drive the economy forward during a time of consumer weakness. The Chart shows the contributions to annual GDP growth from household spending, on the one hand, and business investment on the other. (Public sector investment is also an important part of total investment but is driven by rather different factors to corporate investment, so we concentrate solely on private sector investment here.) Note that household spending has tended to provide a bigger contribution due to the simple fact that it makes up a much larger proportion of GDP – around 65%, compared to business investment’s 10% or so.

The worrying message from the Chart is that previous periods of household spending weakness have also been accompanied by periods of corporate retrenchment, as shown by the circled periods. The early to mid-1990s provides a good comparison to the current situation, given that it also involved a sharp slowdown in household spending as well as a period of fiscal consolidation. Yet as the Chart shows, during this period business investment was just as big a drag on GDP growth as consumer spending. Nor have corporates supported the labour market in times of weakness, by keeping employment high and therefore maintaining some support for household spending. Chart 2 shows that private sector employment plummeted in the recessions in the early 1980s and early 1990s.

But although the corporate sector has failed to provide much of an offset to a weaker consumer sector before, this does not preclude it from being of more help this time round. In the past, both consumer spending and investment were reacting to major adverse shocks, like sharp rises in interest rates or world recessions. But in the absence of such a shock now, it is not necessarily the case that a consumer slowdown will be accompanied by a deterioration in investment. The government is certainly hopeful, expecting real business investment to grow by around 4% next year.

Companies are certainly better managed than in the past, suggesting that firms can better weather any economic slowdown. And on the face of it, the corporate sector is starting to show some green shoots of recovery. Business investment rose by a solid 1.5% on the quarter in Q2 of this year. And the value of mergers and acquisitions (M&A) by UK companies in the UK in Q2 reached its highest level since the start of 2004. Lending to corporates has also picked up.

Meanwhile, the level of firms’ liquid assets is high. Liquidity is arguably a good leading indicator of future corporate activity, given that it represents money that is readily available for them to spend. Corporate money holdings have been climbing since the start of 2003 and are at record levels, both in absolute real terms and relative to corporate liabilities (both bank and bond debt). (See Chart 3.)

The need to invest

But perhaps the most crucial factor determining whether corporate activity, in particular investment and employment, will cushion the blow of the consumer slowdown is the demand for the goods and services companies produce.

And promisingly, although domestic activity is slowing, there are tentative signs of a recovery in external demand, especially in the euro-zone, the UK’s biggest importer. Furthermore, with the sterling trade-weighted exchange rate liable to fall – by around 10% on our reckoning over the next couple of years – on the back of weakening growth and cuts in UK interest rates, UK exporters could benefit from an increase in their competitiveness abroad.

Of course, even if the prospects for UK exports do improve, firms do not necessarily need to invest in extra equipment or hire more workers in order to meet this higher potential demand if they are already operating with a lot of spare capacity.

But survey evidence suggests that firms may now be close to exhausting their spare resources. The CBI’s measure of the proportion of manufacturing firms working below capacity, which has had a close relationship with business investment in the past, points to a pick-up in investment growth. (See Chart 4.)

As such, firms now appear to have worked through the late 1990s investment overhang. High investment in the late 1990s arguably left corporates with excess capital stocks, leaving little demand for further investment. Indeed, nominal investment as a share of GDP has fallen sharply over the last five years to just 9.3% of GDP, the lowest since data began in 1965.

Admittedly, real business investment as a share of real GDP has shown much less of a slowdown, given that the prices of capital goods have been falling relative to other goods, with prices of some IT equipment falling in absolute terms. Nonetheless, it is has still fallen to its lowest level since 1997.

Of course, the slowdown in the housing market has reduced incentives for firms to invest in residential housing. But the construction sector as a whole accounts for just 3% or so of investment; and in any case, it is hard to see how construction investment can deteriorate any further after its 27% fall over the last year.

Other ways to meet demand?

So with spare capacity running out, any prospect of an improvement in demand, from abroad at least, for firms’ goods and services might prompt firms to start spending a bit more. But before we get ahead of ourselves, there are two important ways in which they might yet meet any extra demand without spending more money.

The first is if an increase in productivity allows firms to raise output without having to hire any extra workers. UK productivity growth had been languishing in the doldrums for what had become a worrying length of time before it showed a cyclical pick-up last year.

That cyclical pick-up is now fading, with whole economy productivity growth slipping to 1.4% in the first quarter of this year and private sector productivity growth dropping to just 1.0%. But a potential offset to this cyclical slowdown could come from a structural rise in productivity if firms finally start to reap the rewards of their heavy investment in information and communications technology (ICT) in the early 1990s.

Indeed, the US experience suggests that it can take around five years for the gains from such investment to be realised. And the idea that firms have been busy training up workers in the new technology would help to explain why productivity growth has recently been so weak.

Of course, faster productivity growth is usually regarded as a positive development for the economy, by allowing the trend growth rate of the economy – and therefore living standards and profits growth – to increase. This would boost investment and employment over the medium term. But in the short-term, it would be bad news for the labour market, by allowing firms to produce more output without having to hire any more workers.

We think that a rise of around 0.25% in the average rate of productivity growth over the next few years seems reasonable. Although this sounds small, it could be enough to raise productivity growth from the 1.4% seen in Q1 to 1.7% or so – equal to our forecast for GDP growth this year and implying no need for employment to rise at all.

Meanwhile, the second way in which firms might be able to meet higher demand without spending more money on investment and recruitment is through running down stocks.

Indeed, in previous economic slowdowns, GDP growth has always been pulled down by firms running down their stocks. The circled periods in Chart 7 show that, if stockbuilding is excluded, GDP growth would have been – albeit only slightly – stronger in all of the recent economic downturns.

What’s more, stocks are currently slightly high relative to normal, meaning that there is certainly scope for firms to cut them back in the next year or two. The red line in Chart 8 shows the ratio of inventories in the manufacturing sector relative to manufacturing production. While this has been on a downward trend, due to improvements in supply chain techniques, the ratio of stocks to output is currently slightly above its long run trend.

Meanwhile, although the ratio of retail inventories relative to retail sales has been more variable, it has levelled out over the last few years – with the current level of stocks still above the average since 2000. The CBI’s balances of reported stocks in the manufacturing and retail sectors are both above their averages since 1987.

Both of these sectors might therefore run down their stocks towards their long run trends. Even if the process were spread over the next two to three years, we estimate that it could take around 0.2% off GDP growth per annum.

Do firms have the cash?

So although there might be some need for firms to invest as spare capacity runs out, this could well be mitigated by a rise in productivity or a running down of stocks. But perhaps a more important constraint on firms’ ability to spend their way through the consumer slowdown is the ability of the corporate sector to finance such spending.

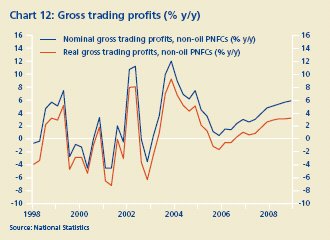

The most obvious source of money for companies is retained finance, or profits. And profits growth has recently gathered a fair degree of momentum. Gross trading profits – the most basic measure – rose by almost 8% in nominal terms last year, bringing profits as a share of GDP back up to its long run average. This profits share tends to cycle around its long run average and has been below it for around five years now, meaning that it could now be time for it to move above it.

This is looking unlikely, however, given that profits growth tends to peak when GDP growth peaks – and GDP growth peaked last year. And on top of any cyclical slowdown in profits, there appear to have been some structural forces pressing down on profits growth, most notably globalisation. Of course, globalisation has helped firms by lowering the prices of firms’ inputs, as well as allowing them to shift jobs to cheaper locations. But at the same time, it has squeezed their pricing power too.

Admittedly, globalisation is not a new phenomenon. And we expect the slowdown in GDP growth to be modest relative to previous recessions. Nonetheless, history suggests that it takes only a small change in GDP growth to affect profits growth. The scales on Chart 11 suggest that for every 1% fall in annual GDP growth, profits growth tends to fall by about 4%.

What’s more, firms are currently facing an additional squeeze on their profit margins from the higher costs associated with the recent renewed surge in oil prices. It is not just firms in the manufacturing sector that have been affected – Tesco, for example, recently attributed a large part of its recent rise in costs to the higher cost of transporting its goods.

As such, any firms that do want to spend money over the next year or two are going to find it hard to find the internal resources to do so. Chart 12 shows that we expect real profits growth to fall into negative territory – i.e. profits to fall outright – before long. And if GDP growth were to be weaker than we expect, nominal profits could fall outright.

Balance sheets have been adjusted

Weak profits growth will therefore almost certainly act as a constraint on firms’ spending over the next year or two. But of course, corporates keen to spend could always borrow the money instead. After all, the cost of borrowing remains pretty low, with corporate spreads close to their historical lows.

What’s more, recent restructuring of balance sheets by firms has perhaps left them in the best position to borrow for a few years. This restructuring took place as a response to the sharp rise in indebtedness at the start of the decade, when firms borrowed to fund the high level of M & A activity.

By cutting investment spending and dividend payments during a period of relatively strong profits growth, the corporate sector has now been in financial surplus, i.e. a net lender rather than borrower of money, for the last two to three years.

This has allowed firms to halt the upward march in corporate debt, in sharp contrast to the household indebtedness situation. In Chart 15, we compare the debt situations of households and corporates. Just as the standard way of measuring household indebtedness is the ratio of household debt relative to their disposable income, the analogy for the corporate sector is the ratio of their debt to profits. Both measures rose during the second half of the 1990s. But while household debt to income has continued to climb, the ratio of corporate debt to profits has levelled off over the past two years.

Nonetheless, corporate debt still stands at close to a record high relative to profits. Looking at a different measure of indebtedness called capital gearing also suggests that corporates might not yet have brought debt back to a sustainable level. Capital gearing is the level of corporate net debt (non-equity liabilities minus cash) relative to their net worth. This is a useful measure to look at given that it is these assets which will ultimately provide the means with which the debt is serviced.

As Chart 16 shows, capital gearing has also fallen back recently. But it still remains above its long-run average. And it is also still some way above the Bank of England’s estimate of the "equilibrium" level of capital gearing of 16%, derived by assessing the tax advantages of debt financing against the higher insolvency risks it carries.

What’s more, these measures take no account of the high pension commitments most firms are now facing. Increases in longevity, together with the fall in expected investment returns, has raised most firms’ pension liabilities, leaving many with a significant deficit on their pension fund.

According to Watson Wyatt, the total deficit among FTSE 350 companies, excluding financial companies, was about £60bn at the end of April. Adding this to corporate debt would leave the improvements to firms’ balance sheets looking much more modest.

Admittedly, surveys suggest that firms themselves are not particularly worried about their levels of debt, with a survey by the Institute of Chartered Accountants in Q1 2005 reporting that a net balance of only 4% of firms believed that their level of gearing was too high. This may be due in part to the fact that, as with households, the low level of interest rates has ensured that the cost of servicing this debt is still well down on the levels seen in the early 1990s, even after the interest rate increases in 2003 and 2004. (See Chart 18.)

Furthermore, the high level of corporate debt does not appear to have prompted the signs of stress seen in the household sector. The number of corporate insolvencies has seen a slight rise since the end of last year, but it has been nothing like the leap in personal bankruptcies seen over the last few years.

But the fact that corporates are having few problems servicing their debt does not mean they are necessarily ready to undo all their hard work in restructuring their balance sheets in the last five years or so by borrowing to fund investment and recruitment. As such, external finance still remains far from an ideal source of funds. Nonetheless, corporates are certainly better placed to borrow than at any time in the last few years.

Firms dislike uncertainty

So a number of constraints face any corporates wanting to increase investment and recruitment over the next year or two. Aside from the fact that there may be ways to meet extra demand without having to splurge more cash, there is the simpler question of whether they actually have the money to spend, be it from profits or external finance.

Yet all these concerns become immaterial if firms decide that they simply do not want to invest, in more capital or more people. And perhaps the most important barrier to their willingness to spend is uncertainty – most obviously about future demand. Even if there are signs of demand picking up, firms might be – quite rightly – unsure about how long this might last. Recent CBI surveys have shown an increase in the number of firms citing both uncertainty about demand and a low net rate of return as factors limiting investment.

The future of the tax regime is another key uncertainty crucial to the prospect for profits growth. For a start, firms are unsure about what will happen to household and corporate tax rates over the next couple of years. Although there is less pressure on Gordon Brown to raise taxes in the very near term, most commentators, ourselves included, still believe taxes will have to rise.

What’s more, aside from the specific tax rises required to put public borrowing back on a sustainable footing, there is a more general uncertainty about the overall direction of the government’s taxation policy. If Gordon Brown were to become prime minister, his more interventionist leanings create the risk that corporates will be saddled with a higher tax burden to finance higher public spending.

Meanwhile, firms will also be nervous about being burdened by further regulation and red tape. Indeed, given all of these uncertainties, it might be the case that if companies do decide to invest, they might decide to do it elsewhere than in the UK.

Corporates to spend cautiously

With consumers and the government no longer able to bear the burden of driving forward economic growth, it is corporates that will come under the spotlight in the next year or two. And the corporate sector certainly looks in better shape than other parts of the economy. External demand looks to be picking up, while firms have used the last few years to restructure their balance sheets. Profits growth has also gathered momentum recently, and there have been some signs that corporates are starting to increase their spending.

As such, the corporate sector is likely to increase its contribution to economic growth over the next year or two. But enough obstacles remain to prevent it giving the economy quite the boost it needs. Any need for firms to invest could be mitigated by rising productivity and the running down of stocks. Their resources are likely to be limited by poor profits growth. And whether firms will ultimately be willing to spend money remains doubtful given the uncertainties they face.

Taking all of these factors together, we think that business investment growth will continue to recover modestly, from last year’s 3.4% to around 4.5% by 2006. However, each 1% acceleration in business investment growth adds just 0.1% to GDP growth. So even if business investment were to continue to post 1.5% quarterly rises as seen in Q2, resulting in growth of 6.0% next year overall, this would still add only to 0.3% to GDP growth.

And this could easily be offset by the 0.2% corporates would take off growth if they ran their stocks back to equilibrium. Meanwhile, even a modest rise in productivity growth of around 0.2% could leave employment growth flat. Given that employment has been rising by around 1% p.a. over the last few years, this could put further downward pressure on household spending and therefore GDP growth.

The upshot is that if we are right in expecting consumer spending growth to remain sluggish, the contribution from the corporate sector will not be enough to keep the economy growing at the rates seen over the last few years, when consumers were spending freely.

To read the full article and Analysis please click here