Executive summary

The Government has made clear that greater local decision-making is a core part of its long-term reform plans. But no broad consensus exists on how localism, decentralisation and the 'Big Society' will intersect or work in any systemic way.

Ministers have championed localism as essential to improve services by devolving power to communities and stripping out government control. By contrast, local authorities expect to take on greater responsibilities through their new 'general power of competence'.

Some common understanding cuts across these interpretations, but there are some clear tensions too, chiefly the precise role of local authorities across each public service in future. Despite new policies that involve decentralisation across health, education and policing, it is not yet clear how responsive Whitehall will be to the new decentralisation agenda.

Until these tensions are addressed, significant uncertainty remains for over 400 councils in England. Given the magnitude of localism as an initiative, there is now an urgent need to build understanding of the challenges around localism, and address systemic dislocation between central and local government. This report, produced by Deloitte Research for local authorities, attempts to do this by describing how localism could be implemented.

Our primary research included interviews with 15 council chief executives who collectively manage over £7.4 billion and employ more than 100,000 people.1 These discussions reveal the following:

- Twelve have no plans in place to address localism in any systemic way. Of these, ten plan to respond through their existing corporate transformation programmes, or be guided in areas such as education reform by national policy.

- Local authority chief executives support the model of public service delivery envisioned by ministers in terms of outputs, but are less convinced of its practical application across public service inputs.

This sentiment supports wider misalignment between central government intent and local government readiness for change. A mix of capability challenges, varying degrees of community participation, and uncertainty around governance and accountability mechanisms could constrain the localism agenda, or limit it to a few flagship reforms that have concrete policy direction such as in health or education.

Through our interviews with local authorities, five specific areas of concern emerge:

Five business challenges

Get users and partners engaged in management and delivery

Councils in England face varying levels of engagement across local communities. Even where there is participation, concerns about levels of capability and capacity may undermine the business case for full-on community involvement in service delivery. Several councils plan to lead a 'first-principles' debate on method, and mobilise communities through a candid discussion regarding the gaps created by spending cuts. Others intend to concentrate resources on a few proven networks to award a greater share of responsibility. But it is not clear what best practice looks like in any systemic sense.

A changing relationship with central government

Chief executives from more ambitious councils regard a better balance between centrally- and locally-financed expenditure through tax decentralisation as key. Local authorities are aware they need to 'do a deal' with leaders in Whitehall who share their vision for the future role of local government in public service delivery. Central departments collectively provide local authorities in England with about £140 billion of funding annually.2 But our research shows councils believe that resistance to change within these departments is widespread. Chief executives view Whitehall intransigence as a key threat to successful implementation of localism.

Understand what is possible

In assessing what is possible, most councils plan to distil their localism activity down to three or four – initially low-risk – programmes. But as several chief executives pointed out, this is not materially different from what is happening already. Once again, there is fundamental misalignment between central government's normative vision of localism, and the practical challenges involved in relying on community networks to manage or deliver public services. Indeed, in a new world of reduced budgets, chief executives will actually need to become more selective about how and on what terms they release funds into the community, or provide in-kind collateral to new enterprises.

Accountability and governance

Installing proper accountability and control mechanisms will be essential. Central government logic is that councils will help community groups devise new measures of success that depart from nationally set performance targets, and agree indicators that are shaped by user experiences. But the real test of localism in modern government will arrive when things start to go wrong. Our evidence suggests that the solution may lie in an incremental approach to risk-taking that builds community, management and political consensus around acceptable levels of risk in each service.

Corporate responses to localism

Although there are a number of examples of successful community programmes, there is no evidence that local authorities have made systemic plans for localism, except in centrally-driven reforms across health and education. Rather, many councils are waiting to have a clearer sense of what 'flavour' of localism actually emerges from the policy debate, and how it will impact on their businesses. Clearly, however, local authorities will need to review their capabilities in key areas and change the mindset of their staff from one of direct control to one of influence. As with many public management challenges, effective leadership will be central to this kind of transformation.

Context: Localism and Decentralisation

Localism has its roots in the Victorian era where, between 1865 and 1875, local government reconfiguration led to a sustained period of civic activism.3 By 1905 the proportion of spending on local government reached its highest-ever level of 51 per cent, compared to about 18 per cent today.4 Historians point to the Local Government Act of 1888 as the last occasion where ministers actively pursued localism as a policy objective.5 Fast-forward to 2011 and the Government made its intentions explicit last year when it stated:

"It is time for a fundamental shift of power from Westminster to people. We will promote decentralisation and democratic engagement, and we will end the era of top-down government by giving new powers to local councils, communities, neighbourhoods and individuals."6

The recent publication of the Localism Bill due for enactment in late 2011 will go some way toward this objective, for example on planning. The piloting of place-based budgeting and specific reforms across health and education also represent the tangible beginnings of systemic decentralisation. In addition, localism will be shaped by a review of local government finance next year.

Yet from the outset, our evidence shows no common understanding of what localism means. A number of chief executives interviewed for this report provided views of how localism will change their businesses, but also recognised that their perspective may vary significantly from that of ministers and government departments. As a result, local authorities are not reconfiguring their organisations for localism with the same energy that they are for, say, budget cuts.

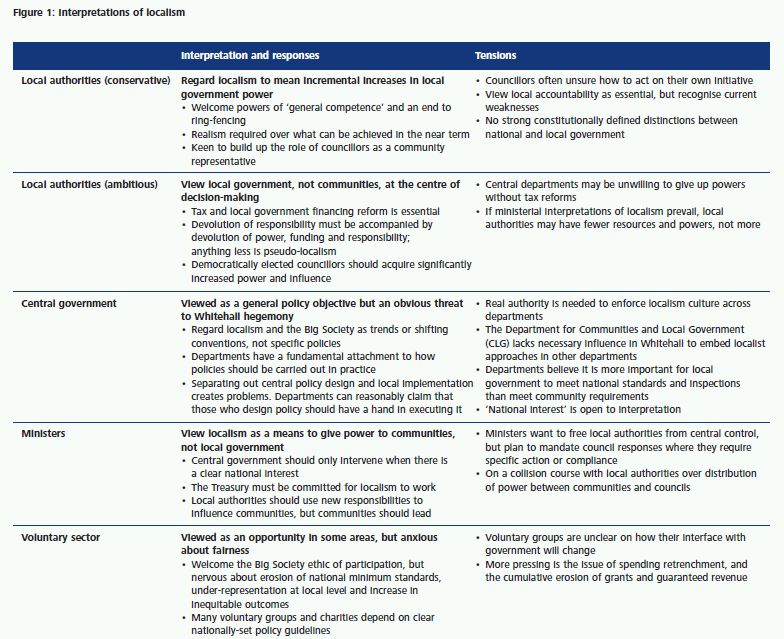

Figure 1 shows several interpretations of localism, but essentially the key tensions are twofold:

1. Ministers view localism as devolution of power down to communities, with transferral of responsibilities from local authoriities to community groups where possible. Yet many authorities are sceptical, particularly around the sustainability of self-appointed volunteer groups. They feel their democratic mandate forms the basis of their right to act on behalf of communities.

2. Councils feel squeezed between central departments (who they feel will not relinquish power and responsibility as easily as ministers claim), and community enterprises, where democratic legitimacy is weaker, or there is widespread uncertainty over the best accountability and governance structures. In response they are taking no real action to prepare for localism, other than to continue experimental or ad hoc community-led projects that have devolved responsibility across some low-risk areas.

These behaviours contrast sharply with a fast moving centrally-driven policy agenda. A general shift toward decentralisation through the Localism Bill is supported by specific reforms across education, health and policing. That work is also taking place within the context of significant spending retrenchment: Central government resource spending on local government will fall to £22.9 billion by 2014-15 – an average cut of 7.25 per cent in real terms across each of the next four years.7 Importantly, these cuts will be front-loaded with 73 per cent of the total reduction concentrated into just two years: 2011-12 and 2012-13.8

In this context, several chief executives were concerned that the cost of stimulating and supporting community involvement through capacity building or tapered funding may outweigh future savings achieved through divestment of services. A minority felt that the experimentation inherent in localism is fundamentally incompatible with the decisive leadership and hard choices required to meet near-term spending challenges.

Key findings

For this research, 15 local authority chief executives ranked five key issues by awarding three points for the most important and one point for the least (see Figure 2). We assess these business challenges below.

Business challenge 1: Get users and partners engaged in management and delivery

Councils in England face problems in driving engagement within local communities. Participation on single issues is significant and sophisticated in some areas, but the level of variation is considerable.

Local authorities agree they have an urgent requirement to, as one chief executive remarked: "Nurture an expectation that people will do more for themselves". Although clear links exist between engagement and socioeconomic background, the results are complex. For example, middle class groups tend to have narrower special interests, but a sophisticated understanding of how to achieve the outcomes they want.

Since public services tend to interface with people from poorer socioeconomic groups, it follows that more people from that part of the community are likely to be involved.9 One chief executive characterised the split as "80:20" – meaning the top and bottom 10 per cent of the community (by wealth) were engaged, with the middle 80 per cent less so. Mobilising this middle 80 per cent will be a key challenge for local authorities in future.

Some chief executives spoke of a need to stop thinking about community engagement through the lens of statutory responsibilities, and begin a dialogue to find different ways to deliver reduced services. Several councils plan to lead a debate on method and work to mobilise communities through a candid discussion regarding the gaps created by spending cuts.

Almost all those interviewed felt that transferring responsibility out of the formal public-sector domain depends on making a series of strategic community investments to ensure new ventures and structures succeed.

This involves utilising a mix of tools that:

- provide seed or tapered funding to launch community projects across areas such as housing, libraries, planning and transport

- offer advisory services to establish revenue streams and financial management best practice " share administration costs of community organisations through in-kind resource or asset donations

- build compelling business cases for community run services and articulate the benefits of citizen involvement by addressing the key engagement question at each step of the process: "What's in it for them?"

- consider the best use of technology to make engagement as easy as possible for the greatest number of people.

Evidence from our interviews suggests that concentrating resources on a few proven networks is the most effective way to introduce localism into local delivery systems. Reliable organisations can then be scaled up to take on a greater share of responsibility. This work necessarily involves 'picking winners' and taking risks that the right people or groups are being set up to succeed.

Business challenge 2: A changing relationship with central government

Decentralisation of the tax system was a key issue highlighted by chief executives. As it is clearly within the realm of public policy, however, we do not discuss it in this report. More widely, a number of those interviewed cited a better balance between centrally- and locallyfinanced expenditure as a key issue.

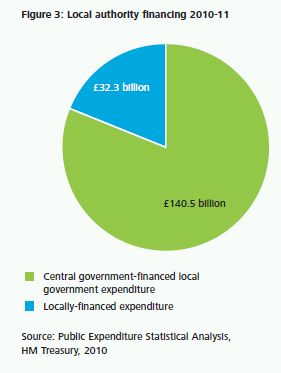

Central government grants to local authorities in the United Kingdom came to around £140 billion in 2010, with English councils alone receiving over £121 billion of funding.10 The overall figure represents about 81 per cent of total funding to local authorities, with the remaining 19 per cent raised locally through council tax, receipts and asset disposals. This rough 80-20 split has been in place since the late 1990s, before which central government contributed closer to 90 per cent of total income.11

Most councils interviewed welcomed the Government's move to end ring-fencing across almost all budgets, although some chief executives were concerned that the change could lead to new tensions with service directors who report to them.

With increasing relative power, it might be expected that local authorities no longer see any utility in a local government superstructure in Whitehall (CLG), but our research shows this is not the case. Local authorities recognise the need for someone "to do a deal with" on each service area, represent their interests in Whitehall, and create the policy framework for systemic or structural changes such as place-based budgeting.

Our evidence shows that chief executives are more concerned about institutional resistance to localism within other government departments, who collectively provide local authorities in England with around £110 billion of funding annually – about 65 per cent of their total spending (see Figure 4).12

Several councils believe the real tension between central and local government on localism will come at this interface and not with CLG. To introduce, for example, new delivery models across health or education over a period of spending retrenchment may place particular stress on key departmental relationships.

Business challenge 3: Understand what is possible

Local authority responsibilities can be arranged across a matrix of complexity and cost with simple services such as street cleaning at one end, and high cost complex services such as social care or education at the other. There are numerous examples of programmes that involve community management or delivery models across basic services.

There are far fewer instances where councils have introduced systemic community participation across complex delivery chains. This has been largely constrained by central prescription – local authorities were not allowed to do it even if they wanted to. If guidelines, specifications and compliance are dismantled in the way ministers describe, however, then localism at scale becomes an issue of capability: What is possible within budgets and acceptable limits of political and operational risk?

Notwithstanding centrally managed reforms of health and education, most councils interviewed plan to distil their localism activity down to three or four specific programmes that involve viable partnerships in low-risk services such as libraries or aspects of children's services. The business case for each programme, which may involve upfront funding, will need to be assessed over at least three years and focus on qualitative financial and other outputs as well as outcomes.

The challenge for localism projects will be to demonstrate that they actually extract net cost from the public purse as well as improve service quality. Interventions at an early stage to assure adequate governance, financial management and controls, and performance management frameworks will be essential.

In a new world of reduced budgets and uncertainty around future service delivery systems, chief executives we interviewed acknowledged they will need to become more selective about how and on what terms they release funds into the community, or provide in-kind collateral to assist new enterprises.

Driven by cost pressure, this posture will reflect a decline in prevention programmes that are typically used to tackle teenage pregnancy, anti-social behaviour or public health. We asked chief executives about these programmes and there was consensus that prevention campaigns had had a mixed record in local government. Investment did not always lead to reductions in adverse behaviour, and when it did, there was no clear evidence that local authority efforts had contributed to this success. To quote one chief executive: "The days of sending out information packs are over".

Similarly, local authorities will need to consider how to make judicious investments to create a small but effective cadre of community organisations and partnerships. Business cases that target sustainability and lock in revenue generation will be essential to support an increasing focus on evidence-based resource allocation.

Business challenge 4: Accountability and governance

Successful implementation of community-based services will change the function of councillors fundamentally. The classic role of representation may give way to community facilitators who provide strong, credible community leadership and are highly visible, but not necessarily responsible for direct service delivery.

Existing analysis of localism often cites the reluctance of politicians to take on responsibility for things over which they have limited control. But as a number of chief executives pointed out during our research, this is already the case in many instances where services or local authority business functions are outsourced.

Installing proper accountability and control mechanisms will be essential to enable community run services to succeed. On accountability, local authorities agree that independent assessments of service performance incorporating community feedback will be essential, but that these processes should be organised locally, and not by national inspection regimes. This approach will drive a diversity of methods to suit local priorities, and over time inadequate accountability and performance management mechanisms could be overtaken by best practice from elsewhere.

Similarly, a priority for councils as they move away from direct funding will be to help community groups devise new measures of success that depart from nationally set performance targets, and agree indicators that are shaped by user experiences. This work could be supported by wider use of technology to enable local evaluation and feedback.

Primary vehicles for governance could range from Local Area Forums to Neighbourhood Boards or Community Associations. These organisations could work closely with the local authority to:

- define the primary units of accountability for a service area. What are we measuring and how?

- provide rigorous performance and scrutiny functions agreed with the local community " identify areas where accountability is essential or non-essential. For example, children's services typically would include a set of clearly defined outcomes. By contrast, libraries that are self-financing may not need significant oversight within the community

- demonstrate the links between the cost of a service and its quality. How are citizens able to access information about performance?

- take on business control functions around resource allocations and strategic investment

- consult closely with the wider community to understand the mechanics of incentivisation.

The true test of localism's utility in modern government will arrive when things start to go wrong. How can local authorities insulate themselves from corporate, legal, financial and political risk in the event of supplier or service failure, or the inability of local structures to provide satisfactory governance and controls? Chief executives offered no easy answers. Problems inherent in principal-agent delivery models apply to a government-community agreement as much as they do to a government-private supplier contract.

Our evidence suggests that part of the solution may lie in preparedness and an incremental approach to risk-taking that:

- builds community, management and political consensus on levels of acceptable risk in each system

- creates contingency structures and frameworks to offset the damage caused by failed delivery models or market failure

- performs an end-to-end review of key processes to identify risks and vulnerabilities. For example, if a Local Area Forum is actually driven by just one or two stakeholders or individuals, what happens in the event that those parties withdraw or move out of the area?

- ensures corporate liabilities such as health and safety, or employer duty of care are considered in building the business case for greater community involvement in service delivery or management structures.

Business challenge 5: Corporate responses to localism

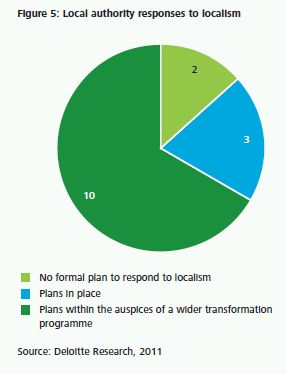

We asked the 15 chief executives if they had formal corporate plans in place to respond to the localism agenda. The results are set out in Figure 5.

These results show that most local authorities regard localism as part of their wider corporate transformation work, and not a standalone reform challenge.

Apart from preparations for cost reduction that inter alia may involve localist approaches, we found little evidence of strategic planning for localism other than responses to concrete policy programmes in health and education. Several councils interviewed felt that they were already 'doing' localism, but only on a low-risk, experimental scale.

We consider these plans and the strategic leadership capability to take them forward as essential for local authorities in future. To execute localism, that is to replace one delivery system and corporate culture with another, local government leaders will be required to understand future requirements and constraints. They must also assume full ownership of corporate responses to localism and develop strong peer networks to build a united vision for what is possible in their local area. Interviews with chief executives suggest that building alliances across political and management boundaries, and flexing collective local government power to ensure the right leaders are installed in central government will also be critical.

Moreover, as localism increases, local authority structures will give way to more flexible models that have less direct control over service areas such as education or social services. Commissioning will become more commonplace, and some service areas will fold or revert to a basic offering as funding ceases. Figure 6 describes how local authorities might look in future.

Several chief executives we interviewed accepted that their current workforce does not meet future capability requirements. Ordinarily they would expect to develop a sourcing strategy or run commissioning programmes in response, but the new realities of public spending mean they are focusing on which business areas to cut, not strengthen. In direct response to localism, the top future competencies required by local authorities are:

- Commissioning skills. This includes vigorous collaboration with other service commissioners across geographies or service boundaries. This also includes building strategic understanding of client groups, developing community consensus on required outcomes and choosing viable organisations with whom to partner.

- Contract management. This includes managing complex contracts across outsourced business areas, controlling risks associated with private and voluntary sector suppliers, improving procurement through joint ventures in, for example, audit or legal services, and working with community engagement professionals and commissioners to consider wider use of 'contracting for outcomes'.

- Community engagement. This includes generating local interest and engagement for community run projects and services, developing a skills matrix to co-ordinate local authority and community expertise, providing advisory services to small enterprises, and creating new technology-enabled channels. Community engagement could rethink the customer contact environment and take forward local variations of place-based budgeting to target funding around vulnerable families and individuals. Councils could also work with experts to devise business cases for community projects that include user charging in their design.

- Asset management. A number of chief executives we interviewed described plans to extract more value from their holdings – particularly estates – to foster community engagement. This includes exploring ways to provide buildings or land free of charge or on long leases with low rents. Across those interviewed, it was felt that more could be done to utilise libraries, youth centres, fire stations, leisure centres, gyms and local authority land for this purpose.

- Voluntary sector engagement. For public-sector managers and elected members, there will be an increasing need to engage partners whose performance can be rigorously assessed through quantitative and qualitative indicators. Managers could also benefit from high quality insight on key engagement risks and understanding of tensions between national and local charities. For councils that manage multicultural communities, it will be essential that voluntary sector partners act in an objective and credible way that reflects the needs of the community as a whole.

More widely, local authorities identified a need to change fundamentally the mindset of their staff from one of direct control to one of influence. The work to dismantle deeply-engrained behaviours and processes within local government has already begun in response to budget cuts, but the success of localism will depend on council staff being able to 'let go'.

Conclusion

The majority of local authorities interviewed for this research have no strategic plan to respond to localism. There is also no consensus over what localism means for councils in England. Even chief executives who are able to specify what localism means for their businesses, also acknowledge that a lack of granularity from central government and a fast moving policy environment makes it difficult for them to act on their analysis.

We must conclude that, as it stands, local authorities are not prepared for localism and decentralisation. This is not a reflection of their corporate responsiveness. Rather, a fundamental set of tensions between government tiers and ambiguities that overlay wider concerns around budget reductions make business planning extremely difficult. Clear policy frameworks are being formulated across health, planning and education, but even with explicit policy direction and strong ministerial steer, uncertainty remains in place.

Whichever interpretation of localism prevails, it is clear that local authorities in England will play a central role in its execution over the next five years.

At present, however, the evidence from this report suggests councils are not confronting the real challenges, which are as follows:

1. We expect significant change to local authority business models

Uncertainty around budgeting, future revenue and capabilities create a series of business change challenges for local authorities. Councils need to understand these challenges at a granular level, including how capabilities and structures may need to evolve to meet future roles and responsibilities. For example, in direct response to localism, local authorities could conduct a fundamental review of their corporate asset bases to understand utilisation, costs, and the financial and legal expertise required to release assets into the community.

2. Within communities, there is significant variance in capability and engagement

There is poor strategic understanding of where community capability interfaces with areas facing cuts. As a matter of urgency, councils need to map which parts of the community have the potential, that is, the capacity, capability and inclination to get involved in either direct delivery or oversight of key business areas. Aligned to this work, local authorities also need to sell the idea of greater community independence and involvement. They need to articulate the reasons why communities should get involved. What is in it for them?

3. There is an urgent need to understand what is possible on a systemic, not just ad hoc or experimental, level

Councils need to build a matrix of organisations to do business with based on their track record, impartiality, corporate structures and their legitimacy. They need to identify which services represent low risk areas where great community involvement can be introduced on a systemic basis. A key challenge will be to understand the capital requirements for new start-ups, and develop business models that build capabilities and long-term financial independence amongst community partners.

4. There are no common standards of accountability and governance

There is patchy or limited best practice around the optimum accountability and governance mechanisms for community-led delivery models. Before localism can be implemented, councils need to develop new frameworks for performance assessment and accountability that meet the specific requirements of a local service, and test these models against user experiences. Local authorities also need to create contingencies to cope with systemic risks and establish clear agreement about where financial and other liabilities lie if problems occur.

Footnotes

1 Deloitte Research, 2010.

2 Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, HM Treasury, 2010.

3 A central role for local government? The example of late Victorian Britain, Simon Szreter, History and Policy, 2001.

4 The Growth of Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom, Alan T. Peacock and Jack Wiseman, UMI, 1961. Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, HM Treasury, 2010.

5 Central Government and the Towns, John Davis, The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

6 The Coalition: Our programme for government, June 2010.

7 2010 Spending Review, HM Treasury, 2010.

8 Ibid.

9 Is the coalition government bringing the public with it? Ipsos MORI, 2010.

10 Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, HM Treasury, 2000 and 2010 report.

11 Ibid.

12 Public Expenditure Statistical Analysis, HM Treasury, 2010.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.