Proposed Statutory Test for Individual Residence

In March this year we reported that progress had finally been made towards a statutory residence test (referred to as the SRT) with the Government promising a consultation document. This was issued in June, and the intention is for draft legislation to be published in December with the reforms being implemented from April 2012. The proposed SRT is set out fairly fully in the consultation document, but some aspects require further clarification or contain traps, and we have made representations in response to the consultation document. Although we expect the basic framework to remain broadly the same, the detail of the SRT may well change in the light of the representations that have been made.

The background

There is currently no full statutory definition of 'residence' and it has been left largely to the Courts to give meaning to the expression. Guidance published by HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) has historically played a central part in addressing the determination of an individual's residence and, following a number of high profile court cases, HMRC issued new guidance in 2009. It is now clear that HMRC do not simply count the number of days that an individual spends in the UK to determine residence but that they will look at all aspects of the individual's life (including their accommodation, family, car, bank account, doctor, club memberships etc). This is very unsatisfactory as it makes it impossible in many cases to confirm with any certainty whether or not an internationally mobile individual is resident in the UK.

Against this background, the proposed SRT is a significant improvement as it will limit and define the factors that may be taken into account when determining an individual's residence status. However some of the definitions are unclear and there are traps and pitfalls that individuals will need to stay clear of if they wish to acquire or retain non-UK resident status – or, indeed, if they wish to be sure that they are resident in the UK because of the advantages that this brings in their own particular circumstances.

The proposal is for the SRT to replace all existing legislation, case law and guidance from 2012/13 onwards (ie as from 6 April 2012) but the current rules will continue to apply for tax years before 2012/13.

Arrivers vs Leavers

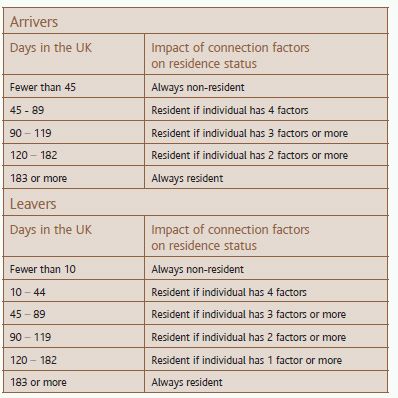

When they determine whether or not an individual is UK resident, HMRC currently distinguish between new arrivals to the UK and UK residents who are leaving the UK. This distinction has been formally incorporated into the proposed SRT to make it harder for someone leaving the UK to become non-UK resident than it will be for someone arriving in the UK to remain non-UK resident.

When applying the SRT the first step will be to confirm whether the individual is:

- an Arriver (someone who was not UK resident in all of the previous three tax years) or

- a Leaver (someone who was UK resident in one or more of the previous three tax years)

When the SRT is first applied in 2012/13 it will be necessary, therefore, first to determine whether the individual was resident in any of the previous three tax years (ie 2009/10, 2010/11 and 2011/12). This is unhelpful for individuals whose residence status is currently uncertain as it means that this uncertainty will continue into the early years under the SRT.

Framework

The SRT will apply not only for income tax and capital gains tax, but also for inheritance tax (where extended UK residence creates a deemed UK domicile).

The test will have three parts: A, B and C.

If, in a tax year, the individual satisfies any of the conditions in Part A they will definitely be non-UK resident in that tax year.

If Part A does not produce an answer, the individual must look at Part B. If any of the conditions in Part B are satisfied they will definitely be UK resident in that tax year.

A high proportion of international individuals with more complex affairs will not find an easy answer in Part A or Part B and they will have to consider Part C.

Part C reflects the principle that the more time someone spends in the UK the fewer UK connections they can have if they wish to be non-UK resident. Under Part C the individual will need to measure:

- the number of days they spend in the UK against

- a small number of defined 'connection factors'

Complex though this may be it does at least enable individuals to balance the two aspects. For example, they can decide to reduce their number of connection factors in order to be able to spend some extra days in the UK.

What is a day?

When individuals count the number of days they have been in the UK during a tax year, they will need to include all those on which they have been in the UK at midnight at the end of the day. There is a transit exemption for days when an individual arrives as a passenger in transit and departs the following day without engaging in any activity (in particular business) that is substantially unrelated to their passage through the UK. Under current HMRC guidance any days spent in the UK by individuals because of exceptional circumstances beyond their control (for example, an illness which prevents them from travelling) can sometimes also be ignored. This concession has not been extended to the proposed SRT and we have included this point among our representations to HMRC on the proposals.

Unhelpfully, for the purpose of counting days spent working in the UK there is a different test of what 'day' means. This is important for those who leave the UK to take up full time work abroad but need to return for, say, meetings in the UK. A day counts as a 'working day' if three hours or more of work are carried out. This is so even if that day does not count towards the general day count, either because the individual was not in the UK at midnight or because the transit exemption applies. This anomaly is confusing and could easily be overlooked by individuals trying to determine their residence status. We have included this point in our representations, and also the fact that it is unsatisfactory that, if an individual works in the UK for fewer than three hours in a day, they will be expected to have sufficient records to demonstrate this fact. This would require them to prove a negative, which is notoriously difficult.

Application of the SRT

Part A: conclusively non-UK resident

Individuals will definitely not be resident in the UK for a tax year under the SRT if they satisfy one of the following three conditions:

- they are Arrivers and are present in the UK for fewer than 45 days in the tax year; or

- they are Leavers and are present in the UK for fewer than 10 days in the tax year; or

- they leave the UK to carry out (or to accompany a spouse who leaves to carry out) full time work abroad, provided they are present in the UK for fewer than 90 days in the tax year and no more than 20 days are spent working in the UK in the tax year.

Part B: conclusively UK resident

Individuals will definitely be resident in the UK for a tax year if they satisfy any one of the following conditions:

- they are present in the UK for 183 days or more in the tax year;

- they have only one home and that home is in the UK (or they have two or more homes and all of these are in the UK); or

- they carry out full time work in the UK.

Residential accommodation is not regarded as an individual's 'home' if it is being advertised for sale or let and the individual lives in another residence. Apart from this there is no proper definition of what would constitute a 'home' for this purpose. This could make it difficult to determine whether or not some individuals have a home in the UK particularly, for example, where young adults have access to their parental home or homes.

Part C: connection factors and day counting

Individuals who do not get a clear result on their residence status from Part A or Part B have to use Part C to take into account a defined number of connection factors to confirm whether or not they are resident in the UK. Connection factors are:

- a UK resident family (ie a spouse, civil partner or common law equivalent resident in the UK and / or minor children resident in the UK where certain conditions are fulfilled);

- accessible accommodation in the UK where use is made of it during the tax year (subject to exclusions for some types of accommodation);

- substantive UK employment, including self-employment, (ie if working in the UK for 40 or more days in the tax year but not working in the UK full time)

- 90 days or more in the UK in either of the previous two tax years; and

- (for Leavers only) spending more days in the UK than in any other single country in the tax year.

Children as a connection factor: an example

Henry left the UK some years ago to work in an offshore jurisdiction. He is (or intends to be) non-UK resident. He is divorced from Angela (who is UK resident) but their arrangements concerning their children are amicable and they both regard it as important for Henry to be part of the children's lives.

The children live in England with Angela but Henry – while keeping a close eye on his number of days spent in the UK – makes a point of coming over to England for birthdays, prize-givings and other special events. The children visit him abroad during the Christmas and Easter holidays, and for a more extended break over the summer.

If, in addition to all the other counting he has to monitor, Henry is not careful to keep within his limit of less than 60 days (including part days) with his children, he could easily find that he has one more connection factor – his children – than he had realised.

Children

A child under 18 who is resident in the UK will only count as a connection factor if the individual spends time with them (one to one, or with others present), or lives with them, for all or part of at least 60 days during the tax year. It does not make any difference whether these days with the child are spent in the UK or elsewhere.

This connection factor has the potential to create real complications, for example for families where the parents are divorced and the children live with the parent in the UK but make substantial visits to the parent who is abroad (perhaps during the Christmas, Easter and summer holidays, plus visits at weekends) and the parent who lives abroad takes times to see the children, albeit briefly, on his or her permitted days in the UK.

A connection factor that lasts one day is enough

A connection factor will be taken into account if it occurs at any point in the tax year. There is no split-year treatment if a connection factor is gained or lost during the year. Individuals who wish to lose a connection factor in order to avoid it affecting their residence status in 2012/13 may therefore need to take action before 6 April 2012.

Balancing connection factors against days in the UK

The way the connection factors are combined with days spent in the UK to determine the individual's residence status in the tax year is set out in the box.

This makes it clear that under the proposed SRT individuals can, for example, be non-UK resident if they spend 90 to 119 days in the UK in a tax year provided that they are:

- Arrivers with no more than 2 connection factors or

- Leavers with no more than 1 connection factor.

There is a sting in the tail however: it is vital to take full account of the fact that, if an individual spends more than 90 days in the UK in a tax year, this will in itself be a connection factor for the following two tax years. This adds an extra factor to the tally of connection factors the individual already had, and possibly taking him or her over a critical threshold.

The potential danger of spending more than 90 days in the UK in any one year: an example

William is a new Arriver in 2012/13. He has a UK resident wife and also accommodation in the UK (ie 2 connection factors). He spends 95 days in the UK in 2012/13 and 45 days in the UK in 2013/14. He will not be resident in those tax years if he does not work in the UK. If William then spends 95 days in the UK in 2014/15, he will become UK resident since he will then have 3 connection factors (family, accommodation and more than 90 days spent in the UK in one of the previous two tax years).

In 2015/16 William will no longer be an Arriver, because he was resident in 2014/15. This means he has now has to apply the more stringent tests for Leavers. As a Leaver with 3 connection factors he will not be able to spend more than 44 days in the UK if he wishes to lose his UK residence.

There is no doubt that the proposed SRT will provide more certainty than is currently the case, and that it is a step in the right direction. That said, it still does not adequately recognise the extent to which modern work and lifestyle patterns can be very mobile, and too much complexity remains. Internationally mobile individuals will need to tread carefully to ensure that a change in their lifestyle in a way they would never normally consider to be a tax matter - for example acquiring the 'common law equivalent' of a spouse who as it happens is UK resident - does not inadvertently add an additional connection factor which makes them resident in the UK. It is a matter of great regret that the Government has not taken this opportunity to introduce a more straightforward SRT which individuals could apply with ease and without the risk of falling foul of circular factors. In particular, the treacherous 90 day connection factor seems unnecessary since the SRT already makes a distinction between Arrivers and Leavers.

Residence, treaty residence, and domicile distinguished

Individuals must bear in mind that the defined connection factors only apply to their UK residence and that all aspects of their life will still be relevant to determining not only their domicile status but also their treaty residence under a Double Tax Treaty (if any) if they happen to be resident in more than one country.

Choosing to become UK resident and the need for a 'statement of residence'

The increased certainty under the proposed SRT is likely to assist individuals who wish to leave another jurisdiction to become resident in the UK as it may become easier for them to show the tax authorities in that other jurisdiction that they have acquired UK residence. However, we would like to see the Government go a step further and introduce a 'statement of residence' (similar to those available in many civil law jurisdictions) which other European tax authorities would accept as evidence of an individual's UK resident status. This would facilitate cross-border movements within Europe.

Tips and Traps

- 'Common-law equivalent' to a spouse or civil partner is not defined and a change in a relationship made without a thought of tax consequences may cause a connection factor to arise (or be lost). This could be sufficient to change an individual's residence status.

- Count carefully the number of days spent with minor children who are UK resident to avoid creating or losing a connection factor. This trap catches both days and part-days spent with a child or children, irrespective of whether those days are in the UK or abroad.

- Clarity is still needed on the meaning of 'child'. For example does it include step-children, or the children of a 'common-law equivalent' of a spouse or civil partner?

- A child attaining 18 and ceasing to be a minor could in some cases remove a connection factor, affecting residence status.

- 'Home' is not fully defined. This could be a problem for anyone, but young adults who still use the parental home to some extent may need to be particularly careful.

- Days will be counted using the midnight test but:

-

- currently the proposal allows no relief for having to be in the UK for exceptional reasons, such as being delayed by illness. If the proposal goes ahead as drafted, individuals will ideally preserve some leeway in their remaining days available in the UK so that they have a reserve for contingencies.

- If non residence is claimed on the basis of 'full time work abroad' then a day is treated as 'worked' in the UK if the individual works for 3 hours. Careful records will be needed.

- A particularly insidious connection factor is that, although an individual with few connection factors can spend a generous number of days in the UK, more than 90 days spent in the UK in any year itself creates a connection factor for the following two years.

- Likewise residence for a single year can cause more than that one year's worth of problems: it 'flips' the individual from the Arrivers' table into the more demanding Leavers' table.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

We operate a free-to-view policy, asking only that you register in order to read all of our content. Please login or register to view the rest of this article.