Originally published in Insight - Human Capital (Pensions), Spring 2008

Public sector outsourcing, including PPP/PFI/BSF, involves work being carried out by the private sector on behalf of the public sector. This represents an important business opportunity, with estimates of current revenues of upwards of £50 bn a year. Most contracts involve a transfer of staff from the public to the private sector, and there are increasingly onerous and complicated pension requirements being made of contractors, the latest arising from the "Best Value Authorities Staff Transfers (Pensions) Direction 2007".

Typically, tendering for contracts is a competitive process. Margins can be tight. It is therefore important that the contractor factors the right "price" for pensions into its bid. Too cautious an approach could lose the tender, too aggressive an approach could mean pension losses dwarf the profits over the period of the contract.

Contractors need to consider how to reflect pension risks in their bids, ideally in a way that is consistent with the way that the business assesses the risks across other aspects of its bid. Ideally, contracts should be awarded to the best provider services being outsourced, rather than on how much pension risk a contractor is prepared to take.

What Are The Issues?

Few investors would buy a business with a defined benefits ("DB") pension scheme without doing detailed due diligence. It is hard to argue against carrying out equivalent due diligence before acquiring new contracts. It is vital for a contractor assessing the profitability of a contract bid as a whole to take due account of the associated pensions risks. Any assessment of this will be sensitive to the assumptions used, so judgment will still be needed by the contractor, and we return to this later. If the potential pension cost is such that the contract could prove unprofitable in certain extreme circumstances, the contractor might need to avoid the contract altogether. The contractor will need to decide what "extreme" means, and this will depend on its appetite for risk.

This is all the more important where there is a choice between an Admission Agreement (whereby the employees remain in the LGPS and the contractor pays into it for the duration of the contract) and a "broadly comparable" scheme.

For Admission Agreements, at the end of the contract the contractor will typically be liable for any deficit, calculated in the Cessation Valuation. The risks can be valued by considering the impact of interest rate and equity risk on the final deficit, which might not be calculated on the same basis as the ongoing funding basis. The risk is asymmetric as the contractor will rarely benefit from any surplus built up.

For a "broadly comparable" scheme, at the end of the contract the contractor will remain responsible for any pension liabilities which are not transferred on. These could be assessed using a "risk free" rate or a proxy insurance buy-out price. Arguably, we need to consider the solvency deficit regardless of whether a Section 75 debt is expected to be triggered at the end of the contract as the contractor will remain liable for the financial cost of the pension promise. A key difference from Admission Agreements is that we should consider the cash flows for benefits expected to be awarded over the duration of the contract – these typically will continue for many decades after the contract has finished.

While the risks of additional contributions following a Cessation Valuation are material, for a contractor at least this represents a clean break. With a "broadly comparable" scheme, the contractor can remain on risk for many decades after the contract is terminated, as shown below:

Benefits Being Promised

Sample scheme - future service liabilities

It is possibly in part for this reason why Admission Agreements can be attractive to contractors, in particular those who do not have (or are winding down) an existing final salary scheme. In addition, the Admission approach can give some flexibility for risk sharing between contractor and awarder, and we discuss this further below.

Two Pricing Routes

The risks should impact on contract pricing, and the asymmetry (whereby any funding surplus at the contract end will normally only be available to the awarder) should make any contractor price pensions more cautiously than an awarder would. By passing risk back to the awarder, the contractor should be able to quote a lower cost, related more closely to the actual cost of the services it will provide. The contractor may then be able to put a strong business case to the awarder for it to agree to some indemnities, including:

- Capped contributions (awarder picks up any excess)

- Variable rate, subject to maximum (cap) and minimum amounts (collar)

- Fixed contributions (awarder benefits / loses depending on actual costs)

- Awarder picks up any deficit at the end of the contract

- Awarder keeps risks in respect of service prior to contract commencement

Admission Agreements – How To Assess Risks?

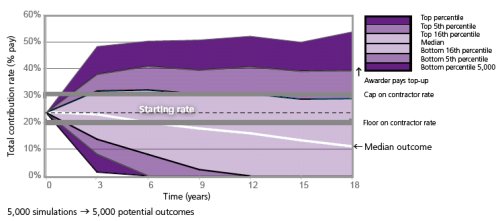

Different degrees of "risk ownership" can be devised, and creative solutions can be identified that give good value for the contractor and the awarder alike. For example, the chart below shows that the awarder should "win" more often than not from a "cap and collar" on the contributions paid by the contractor, while the contractor can agree (relatively) stable contributions with greatly reduced risks than where there is complete freedom to require contributions from the contractor.

Cap And Collar On Contributions

What Basis Should A Contractor Use To Make Its Assessment?

Perhaps the starting point might be the "economic cost". By this we mean the value taking account of how financial markets might price the cash flows, in the same manner as it might arrive at the pricing of a derivative contract, Broadly, this may involve discounting in line with government bond yields (and we note that the Accounting Standards Board is contemplating changing FRS17 to require discounting in line with such yields, rather than higher corporate bond yields). A contractor may be willing to allow for pension risks below their economic cost in preparing a bid, but the economic cost should be a minimum level used in the assessment of the profitability of the contract.

What Will The Contractor Do With This Information?

The contractor can decide the risk it is prepared to accept, and compare the expected costs with the expected profits. Depending on its appetite for risk, the expected costs, and the expected profits from any given contract, the contractor can decide whether to adjust its bid price, negotiate for extra pension assets, seek indemnities from the awarder to lock out most of its risks, or, in extreme cases, walk away from the deal.

For an Admission Agreement, the contractor is also able to illustrate clearly to the awarder that passing pension risk to a contractor should affect the price bid for the contract, and it may not be in the awarder's interests to pass on the risk, if the price is excessive.

Later Generation Contracts

The above can apply equally to second and subsequent generation contracts where contractors may be required to offer a more complicated range of benefits, depending on when the original contract was let, and what terms new hires have been offered. An additional aspect of concern can relate to the funding position of any liabilities being taken over from the previous contractor's broadly comparable scheme.

The importance of proper pensions due diligence can only increase, as can the need to allow properly for the pensions risks being taken on.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.