With recent advances in computer technology, AI and ML are increasingly being used in products and services for the healthcare industry, such as in breast cancer screening, stroke detection and patient monitoring, and to assist in the creation of new drugs and antibiotics. Statistics from the World Intellectual Property Organisation also show increasing numbers of AI related patent applications being filed in the Life and Medical Sciences sector. It is, therefore, important to understand what types of invention can be protected in this area and why.

Requirements to be technical

For an invention to be patentable in Europe, it must be novel and inventive over what is currently in the public domain. However, for computer-related technology, particularly in healthcare applications, it is also important to consider the further requirement for inventions to be technical. Whilst the term technical is not explicitly defined in the European Patent Convention (EPC), which provides the framework for the European patent system, features falling under the patentability exclusions of the EPC are not considered to be technical by themselves. These include:

- These requirements and exclusions create a complex landscape which must be navigated in order to achieve patent the relatively narrow exclusions of mathematical methods and computer programs, which are relevant to AI/ML inventions; and

- the perhaps broader exclusions of methods for treatment of the human or animal body by surgery or therapy and diagnostic methods practised on the human or animal body, which are relevant to healthcare related inventions.

protection for healthcare inventions in AI and ML. We have identified some example European patent cases, which are useful for understanding where the boundaries lie.

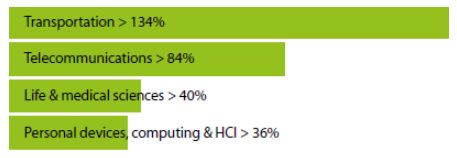

AI in industrial sectors

Highest growth rates (in patent filings between 2013 and 2016)*

Case examples

- Board of Appeal decision T598/07 relates to a neural network-based analysis of ECG signals, which reduces false positive detections of heart conditions in patients. This case demonstrates that an AI/ML based analysis of medical data can form part of a patentable invention.

- T1779/14 relates to an insulin pump having a self-learning engine to dynamically update a small touchscreen interface depending on changing user preferences at different times of day. This case demonstrates that a self-learning engine can be used to provide a technical effect, in this case to provide an improved humanmachine interface.

- European patent EP3065641 relates to a system for assessing a mental-health disorder in a human subject using a trained ML model. This case demonstrates that a system that facilitates a new and improved diagnosis of a patient can circumvent the method of diagnosis exclusion and that facilitating a new and improved diagnosis can be considered to be a technical endeavour.

- Pending patent applications EP3596697 and WO2019160557 also provide interesting insights into the current thinking of the European Patent Office (EPO). EP3596697 relates to the use of a trained neural network to generate a patient-referral decision. Early indications from the Examiner are that merely using a trained neural network to generate the referral decision over other methods is not enough for patentability, but perhaps aspects of the way in which data are prepared for input to the neural network could be patentable.

- WO2019160557 relates to a system for processing medical text and images using a chain of ML models. It would seem that merely using ML to perform what the Examiner considers to be a nontechnical task is not enough for patentability.

It can thus be seen that AI/ML related healthcare inventions can be patentable in Europe, but the invention needs to provide a technical solution to a technical problem that does not fall foul of the various patentability exclusions set out in the EPC.

Who can be an inventor?

In another interesting development, we have now seen written decisions issued by the European Patent Office on some landmark cases relating to AI. In 2018, two European patent applications were filed by Stephen L. Thaler declaring an AI entity DABUS as the sole inventor. The European Patent Office objected to this, and a hearing was held with the applicant. A decision was issued in November 2019, with the full written rationale following in January 2020.

In short, the EPO decided that an AI entity could not be named as an inventor, and so the applications were refused on the basis that no valid declarations of inventorship were filed. The rationale of the European Patent Office was that inventors needed to be natural persons. In addition, DABUS was neither a natural nor legal person and so could not hold property. Therefore, there could be no transfer of ownership of the invention from DABUS to the applicant.

Thus, for now at least, it appears to be impermissible for an AI entity to be named as an inventor on a European Patent application. It remains to be seen, however, whether more widespread inventing by AI entities could lead to a change of law in the future.

Click here for more information and more case examples >**

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.