With MiFID and CRD lurking ominously on the horizon, an ever-more determined Chancellor set to impose further legislation restricting opportunities to remunerate key employees in a tax-effective manner, and the challenges of retaining and recruiting good staff constraining the growth prospects of UK business, we ask what lies ahead for the financial markets and how will it affect your firm?

CRD – Are You Ready?

Article by Neil Fung-On

Few investment firms are fully prepared for the impact of the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD). In fact, where resource is a constraint, many are unlikely to have even read the consultation document. In this article, we address some of the key considerations for firms in this position.

The consultation period for ‘Strengthening Capital Standards 2’ (CP06/3) ended on 28 April 2006 giving interested parties little time to digest and assess the impact of over 1,300 pages of consultation and draft rules. With the feedback statement due in July and the finalised handbook rules and guidance in October, what should investment firms be doing to prepare?

Scope

Only investment firms subject to the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) must meet the requirements of the CRD (the re-cast Capital Adequacy Directive). The Financial Services Authority’s (FSA) consultation paper ‘Organisational systems and controls’ (CP06/9), Annex 5: Perimeter Guidance (MiFID and the Recast CAD Scope) Instrument 2006, provides useful information for firms making this assessment ( http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/cp/cp06_09.pdf).

Categorisation

The next step for CAD investment firms is to establish their base capital. The table below summarises in high-level terms how existing CAD firms will be categorised under the recast CAD. However, you will need to consider whether changes in MiFID compared to the Investment Services Directive impact on your base capital consideration.

Firms must then ascertain whether they are a limited licence, limited activity or fullscope BIPRU investment firm. Although the consultation provides some guidance in this area, a detailed chart of which permissions need to be limited or restricted in order to meet the FSA’s requirements has not been produced. The FSA’s consultation paper ‘Organisational systems and controls’ (CP06/9), Annex 5: Perimeter Guidance (MiFID and the Recast CAD Scope) Instrument 2006 again provides a decision tree which goes part of the way there (http://www.fsa.gov.uk/pubs/international/draft_guidance.pdf).

Impact on capital resources Requirement

Investment firms will calculate their capital requirements in line with the following.

Limited licence investment firms apply the higher of:

- base capital resources (50k or 125k)

- credit risk (CR) + market risk (MR), or

- fixed overheads requirement (FOR).

Limited activity investment firms apply the higher of:

- base capital resources (730k), or

- the sum of CR + MR + FOR.

Full-scope investment firms apply the higher of:

- base capital resources (730k), or

- the sum of CR + MR + operational risk capital requirement (ORCR).

Timing and transitional provisions

The CRD will come into force on 1 January 2007, but the transitional arrangements will be effective until 1 January 2008. This will allow firms to delay applying certain aspects of the new requirements.

It is likely that many investment firms will decide to delay the transition to the new CR rules and, as a consequence, will also delay implementing the new pillar 2 (individual capital adequacy) and pillar 3 (rules of disclosure) requirements.

Regardless of these transitional provisions, the following elements of the new regime will apply from 1 January 2007:

- capital definition, FOR and new base capital requirements

- a new consolidation regime for groups

- trading book definition and updated Position Risk Requirement (PRR) and PRR for foreign exchange risk

- systems and controls requirements which are currently being consulted on in CP06/09.

However, firms cannot afford to delay in considering the impact as firstly the changes may affect the level of capital they hold and secondly, certain waiver applications will need to be made well in advance of 1 January 2007.

Firms should therefore undertake the following practical steps before 1 January 2007.

- A review of their capital to ensure that the new definition can be met.

- Applications for varying permissions to ensure correct categorisation.

- Application for a ‘CAD waiver’ where investment groups can meet the exemption criteria.

Looking ahead

As we approach 2007 the CRD is only one element of a significantly changing regulatory environment. Smith & Williamson can help your firm prepare for these changes so that when they come into force, there is minimal disruption to your business.

Key definitions

CR – The CRD introduces advanced methods for calculating credit risk. However, for small, limited licence and limited activity firms the FSA has created a simplified version of the standardised approach and, in reality, most of these firms will continue to apply the IPRU (INV) 9 Chapter 10 and 5 rules through 2007 as allowed by the transitional rules (see below). Firms should however also note changes to the calculations of counterparty credit risk in chapter 13 of the BIPRU.

FOR – This replaces the expenditure base requirement and will apply from 1 January 2007.

ORCR – Firms can adopt one of three methodologies: the basic indicator approach, the standardised approach or the advanced measurement approaches. The adopted approach will largely depend on the size, nature, scale and complexity of the firm. The CRD also allows for national discretion to exempt some investment firms until December 2011. The FSA has specified certain conditions under which this exemption may be applied.

Converting to an LLP

Article by Colin Ives

A number of firms in the financial services industry are looking to convert to Limited Liability Partnership (LLP) status. But what is driving this desire for conversion and are LLPs the structure of the future?

Prior to the introduction of the LLP Act 2000, which came into force on 6 April 2001, firms trading as partnerships invariably did this under the 1890 Partnership Act. This meant that all partners had joint and several liability for the debts of a firm, with a large-scale claim against a firm potentially resulting in the bankruptcy of all partners.

The new LLP structure removes this burden such that, in most cases, a partner’s liability in such a scenario would be restricted to the loss of his/her interests in both his/her capital and undrawn profits within the firm. In some circumstances the individual partner or partners who provided the defective advice may still retain a degree of unlimited liability.

Therefore, it was fairly rare for a business within the financial services industry to be structured as a partnership. Directors involved in such businesses preferred to obtain the limited liability protection afforded by a limited company. However, a limited company has a far less flexible structure, with remuneration often requiring shareholder approval and any profit distribution being assigned to shareholders in their pre-existing shareholding ratios. This often results in rewards for a successful year being paid out as remuneration via a bonus or possibly being distributed more widely to a shareholder group, much to the chagrin of the individual whose performance created the profit for the business.

Obviously, most shareholders would recognise the performance of the individuals concerned and wish to reward good performance via remuneration. The difficulty here is that while such bonuses are liable to income tax and employee National Insurance (NI) in a manner similar to that of a partner in a partnership or LLP, there is also the additional burden of employers’ NI at 12.8%, which would have to be paid to the Treasury. On a bonus of £1 million the additional £128,000 employers’ NI liability can be a significant burden. However, if paid as a profit share from a partnership or LLP, the employer’s NI falls away, although there are other minor differences that may affect the total saving.

Therefore, as a result of the introduction of the LLP structure, many businesses within the financial services industry are seeking to change their structure to take advantage of the LLP format. This enables greater flexibility in structuring the business and in rewarding individuals for past and existing performance, as well as making a significant saving in the amount of money paid to the Treasury.

Where a business is reliant upon a few key individuals, it is often better to have an LLP structure to enable the business to reflect more closely the performance of the individuals concerned. Where an existing business wishes to convert to LLP status, several issues need to be considered, particularly in relation to the value attached to the existing business. However, with careful advice and planning, most hurdles can either be circumvented or dealt with in such a way that they do not crystallise until a future date, by which time the significance of the burden may well have eased through the passage of time and inflation.

AIM – the first XI

Article by John Cowie

AIM is 11 years old this month. It has enjoyed some outstanding publicity recently, which is no doubt one of the reasons why Deutsche Börse, NASDAQ, Euronext and Macquarie have been circling the LSE with interest. Some background might help to explain the phenomenon.

The Alternative Investment Market, as it was then known, was set up in 1995 to help those companies looking for public capital which were too small or at too early a stage in their development to join the LSE’s Official List. Those responsible for its formation cleverly reasoned that a market which encouraged smaller, less developed businesses to float and granted them access to public capital would flourish in time. To do this, they decided to allow these companies to come to market with no trading record, no requirement to sell shares to the public and no minimum market capitalisation.

Even the tax authorities looked favourably at the market and – to encourage the grass-roots investment which the market set out to attract – deemed the shares of its participants unquoted for tax purposes. This allowed private investors to enjoy capital gains and inheritance tax reliefs. To help with the administration of the market, LSE came up with a unique solution – let the market regulate itself (albeit with a network of independent Nominated Advisers [Nomads] to police that regulation). This family of Nomads forms the backbone of AIM’s reputation and success. Yet despite this the junior market’s supporters have had a tough job convincing everyone of its credibility.

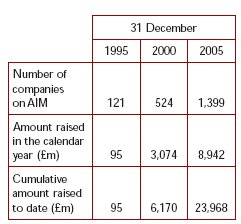

There were ten companies on the market at the outset; it had some bad press, few institutions gave AIM a second glance in the early years and private client brokers were key to raising capital at that time. But even with an inauspicious start and a few tough years, AIM, as it became called, gradually started to win favour. The number of companies joining AIM and the funds those companies raised showed steady growth, as shown below.

With a combination of attractive tax breaks for private investors and Venture Capital Trusts, a lighter touch regulatory framework, and a critical mass that generates its own momentum, AIM’s place seems assured. Even the cynics have stopped scoffing. However, with a public image and much vaunted success comes public scrutiny when things go wrong.

No-one could have missed the debacle which was Regal Petroleum. And what really happened to allow investors to lose so much money on Langbar International? Clearly, market forces will be what they will and companies cannot control which industry sectors fall in and out of favour. What seems obvious to us though is that AIM’s success depends principally on its reputation. That reputation, uniquely among stock exchanges, relies in large part on the family of Nomads to whom responsibility for much of the interpretation and application of the AIM Rules is devolved. This is a function of what AIM set out to do: to offer a more lightly regulated market to assist smaller, growing, emerging companies to find growth capital in the public markets.

If a problem arises, the first port of call should be the Nomad to determine whether they fulfilled their responsibilities. Were they duly diligent in bringing the company to AIM? Did they continue to monitor the company’s adherence to the Rules? If AIM is to continue attracting publicity (which it needs to do if it is to continue flourishing), then Nomads need to ensure that their job is done methodically and diligently. They should then have nothing to fear from AIM’s prodigious growth but a rapidly increasing workload!

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.