Executive summary

- The Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 authorises local authorities to delegate decision-making powers to their officers. This is done by scheme of delegation.

- The Planning etc Scotland Act 2006 required Scottish local authorities to prepare new Schemes of Delegation to determine the planning applications for developments classed as local under the new hierarchy of developments.

- The new schemes were an opportunity to enhance efficient decision-making by avoiding the delays involved in decisionmaking by committees of councillors.

- Brodies audited all 33 of the planning authorities' new Schemes of Delegation.

- The audit indicates that there are very wide variances in the amount of delegation. This has significant implications not just for the efficiency of decision-making, but also for the jurisdiction of the new Local Review Bodies. It also creates a lack of certainty for applicants and agents submitting applications around Scotland.

Introduction to Schemes of Delegation

Schemes of Delegation (SoDs), which have existed since 1973 ("the 1973 scheme"), provide a framework by which planning authorities delegate certain decision-making powers to officers rather than to elected members of the authority sitting on a committee. Until 3 August 2009 (when section 43A of the amended Town and Country Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 came into force), each planning authority operated under a single 1973 scheme. Section 43A introduced a new additional scheme which is to run alongside that of the 1973 scheme.

For those applications which do not fall within the new 2009 schemes, they will be decided by the elected members sitting as the planning committee, rather than the appointed planning officer.

New Schemes of Delegation for local developments

The 2009 schemes are part of the changes to the development management system introduced by the Planning Etc Scotland Act 2006. According to the Scottish Government:

"Changes to development management are intended to ensure that procedures for applying for planning permission are fit for purpose and responsive to different types of development proposal; that they improve efficiency in developing and determining applications and enhance community involvement at the appropriate point in the planning process."

(Circular 4/2009 "Development Management Procedures" paragraph 1.3)

The rules on the new 2009 schemes are:

- Each planning authority was required to prepare a new scheme of delegation. The authority has a duty to keep the scheme under review, and prepare fresh schemes at intervals of no greater than every five years or whenever required to do so by the Scottish Ministers. The only procedural requirement is that the scheme cannot be adopted by the planning authority until it has been approved by the Scottish Ministers. There is no requirement for consultation with stakeholders. Once adopted, the section 43A scheme must be published on the internet and a copy made available for inspection at an office of the planning authority and in all its public libraries.

- New 2009 schemes only apply to planning applications for local developments, which are developments other than those classified as national or major. For example, all applications for less than 50 houses are local developments. In consequence, developments of significant importance have the potential to be decided by officers under delegated powers.

- The only restriction is that a new scheme cannot delegate determination of an application for planning permission made by the planning authority or by a member of the planning authority, or an application relating to land in the ownership of the planning authority or to land in which the planning authority have a financial interest (the Town and Country Planning (Schemes of Delegation and Local Review Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2008).

- Even if the new scheme delegates decision-making power to an officer, the councillors may, if they think fit, decide to determine the application themselves (section 43A(6)).

New appeal process: Local Review Bodies

Where a planning application is determined by an officer acting under a new scheme, there is no right of appeal to the Scottish Ministers. Instead the officer's decision is challenged by applying to the Local Review Body (LRB).

The LRB is a committee of the planning authority comprising of at least three members (councillors) of the authority.

The consequence of the new 2009 schemes is therefore that both the first instance and appeal decision on a delegated planning application are made at the local level.

Research methodology

Brodies audited all 33 of the planning authorities' new 2009 schemes. The objective was to assess the extent to which these schemes contribute to:

- the goal of the Scottish Government to "improve efficiency in developing and determining applications"; and

- "The Scottish Government's expectation is that Schemes of Delegation provide maximum scope for officials to determine planning applications, thus ensuring elected members focus on complex or controversial issues." (Scottish Planning Policy para 26)

Delegation is a means of improving efficiency, because the decision is made by the officer, as opposed to the officer preparing a report to the planning committee, with the attendant administrative tasks, and the delays inherent in waiting for space in the agenda of the next committee meeting. There is also the risk that the committee decide to continue determination of the application to a future meeting, for example to enable a site visit to be held.

The Regulations prescribe few restrictions on delegation, and therefore enable local authorities to delegate widely. The audit sought to identify how much further authorities had gone into introducing additional restrictions on delegation.

As the 2009 schemes vary significantly, the audit grouped restrictions on delegation under the following categories:

- discretion of the appointed officer to send the application to the planning committee for determination

- the type of applicant

- whether the application is contrary (or significantly contrary) to the development plan

- whether the application raised environmental issues

- the number of objectors to the planning application

- whether any of the statutory consultees or the community council objected to the planning application

- whether the scheme adopted the restrictions imposed by the 2008 Regulations only, and did not include any further restrictions on delegation

Key findings

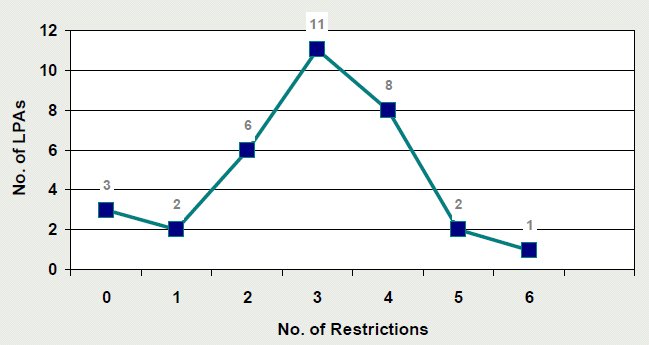

- There are very wide variances in the amount of delegation. Three local authorities (9%) have maximum delegation, as they imposed no further restrictions on delegation beyond the requirements of the 2008 Regulations. Twenty two authorities (67%) adopted schemes with restrictions in three or more of the categories mentioned above.

Line graph illustrating the number of local authorities against the total number of restrictions within their SoD

- There are also very wide variances in the types of further restrictions on delegation.

- The most frequent restriction is to prevent delegation where objections have been received to the planning application. The relevant number of objections varied from 3 up to 10. In some instances multiple objections from the same household are to be counted as a single objection, and some schemes clarified that only objections raising valid planning issues would count.

- The other most common restrictions are where there is an objection from a statutory consultee or community council, or the application is contrary to the development plan.

Bar graph illustrating the most popular restrictions incorporated into the 2009 schemes

Analysis and comment

These key findings illustrate the difficulty local authorities face in balancing democratic accountability in planning decisionmaking against the desire for efficiency.

The most efficient approach is to delegate all decisions other than those which the 2008 Regulations prohibit from being decided by officers.

The conundrum is how some authorities can justify taking this approach ("councillor-lite"), whereas others have introduced additional prohibitions on delegation, and in some instances a significant number of additional prohibitions ("councillormax").

This conundrum is most keenly raised by applications which are contrary to the development plan. The Scottish system is plan-led, so a case can be made for requiring councillors to make the decision whether permission should be granted for a development which is contrary to the plan. However, the Scottish Ministers chose not to include this as a restriction in the 2008 Regulations. They also approved schemes which do not prevent officers making that decision under delegated powers.

The clear implication is that delegation is appropriate. The question is why it is appropriate for some authorities, but not others.

The other types of restrictions can all be justified to some extent because of the potential for significant issues to be involved. The same question remains: why is that potential important enough for some authorities to prohibit delegation, but not others?

The easiest restriction to criticise is the prohibition on delegation where a specified number of objections have been submitted to an application. This is a populist approach, designed to show that councillors are taking account of significant opposition to a development. However, such an approach focuses on the quantity rather than the quality of objections. Also, the number of objections which triggers the prohibition on delegation is often set very low.

Conclusion: some practical implications

Planning officers and elected members now have different roles to play in the planning process. Even if their new scheme copies the old one, there is now the prospect of delegated decisions being appealed to the councillors sitting on the LRB. They must adjust to the new procedures, ensuring efficiency is matched by impartiality.

However, there is such a marked inconsistency in approach to delegation across Scotland that this will put pressure on applicants, who will have to check the individual schemes to identify whether delegation applies to their application. As well as affecting who decides the application, this also has significant implications for timing. For instance, the time limit for determining an application cannot be extended by agreement if the application is determined under delegated powers. Care will now have to be taken to ensure that the time limit for submitting a deemed refusal does not expire.

With the current mosaic of SoDs, we are likely to see new tactics emerge. Applicants will have to consider whether permission is more likely to be granted by the planning officer or the councillors, both at first instance and on appeal. If an applicant anticipates a better outcome from councillors, or wants to preserve the right of appeal to the Ministers rather than LRB, a development could be designed to avoid delegation. It could be scaled to be a 'major development' (although this designation has other implications which need to be taken into account), or so that it triggers a restriction in the scheme which prevents delegation.

Wider delegation certainly keeps appeals at the local level. However, there is no third-party right of appeal to the LRB, so councillors have to rely on call-in powers to prevent a grant of permission under delegated powers. Authorities which do not delegate widely to their officers increase the risks of their decisions being overturned by the Scottish Ministers' reporters on appeal.

All local authorities have a duty to prepare fresh schemes at least every five years. It will be interesting to see what, if any, new approaches emerge.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.