- in United States

- within Energy and Natural Resources, Intellectual Property and International Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit and Metals & Mining industries

"The major discovery is good

news for Egypt

but will likely impede Israel's much-delayed

plans to exploit and export its own offshore

reserves."1

1. Introduction

The role of natural gas in economies has been growing steadily, and various areas of gas usage have become indispensable to achieve economic growth and societal prosperity. In three major areas, i.e. district heating, industrial fuelling and power generation, natural gas has become the fuel of choice in many jurisdictions. Although problems still do exist concerning security of supply, regional markets, oil-price pegging and market liberalization, for many countries gas is still on the forefront of the energy agenda.

For countries that do not have their own gas deposits, import dependency turns out to be a substantial concern. Not only the potential will and the ability of the resource-holder countries to use natural gas as a political weapon but also the political instabilities in the transit countries have been one of the issues that raise concerns in the consuming countries. These concerns led the consuming countries to search for stable suppliers with safe routes for delivery.

In this short essay, we will briefly analyze the possibility that the gas resources newly developed in the Israeli exclusive economic zone (EEZ) be transported to European markets through Turkish territory. Among various options, the Turkish-Israeli "re-rapprochement" after the crisis between Russia and Turkey highlighted that Turkey is still a viable option for marketing Israeli gas. Our perspective in analyzing the matter will rest on three pillars:

- The gas demand in the European Union (EU)

- Turkish gas market

- Alternatives for Israeli gas

A few comments will also be made on the impact of the US and Australian liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports and their potential in changing the game and leading a leapfrog in gas markets.

2. The gas demand in EU

The European energy policy faces three fundamental challenges, and the policies shaped have to address these challenges at the same time.

- Security of supply

- Successful energy transition

- Competitiveness

The faster than expected decline in Europe's gas reserves and accelerating tensions with Russia are the two main sources of security of supply concerns. Shale gas potential in Europe is still far from being a game changer as it is in the US. Thus, EU gas demand is still primarily met by Russian supply and alternative routes for Europe still means non-Russian routes.

The EU imports nearly 70% of the gas it consumes, and Russian gas represented 29% of supplies in 2014, compared to 23% from Norway, 4% from Algeria and 10% in the form of LNG. Europe's import needs have fallen, despite the 25% reduction in its domestic output between 2010 and 2014. Total EU imports thus fell to about 280 billion cubic meters (bcm) in 2014 (compared to 336 bcm in 2010).2 Today, Russia's export capacity to Europe is more than 190 bcm, passing through Ukraine (Brotherhood – 1967), Belarus (Yamal-Europe I – 1994) and Germany (The Nord Stream – 2012).

Gas demand in EU has been declining since when it peaked in 2010. Indeed, EU gas demand has rapidly fallen since 2010: demand in 2013 was 14% lower than 2010 levels and this despite 2013 being colder than normal. Demand fell by a further 11% in 2014, which was an exceptionally mild year. In 2014, gas demand was the lowest it has been since 1995. Eurogas estimated that every member state saw a decrease in gas demand between 2013 and 2014, in great part because of mild temperatures.

Demand is expected to grow in the long run as the European economies catch up with their traditional growth levels and there is little evidence that the EU countries will do away with the nuclear phase-out started after Fukushima. The upper-bound projection from Eurogas is for an increase in consumption of more than 50% by 2035 compared to current levels, and even their lowest estimate represents a 15% increase on 2014. Latest projections of the European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas (ENTSO-G), used to plan gas pipeline investment, range from a 13% increase in EU gas demand to 2030 in its lowest scenario, to a 35% increase by 2030 in its high scenario.3

In order to address the security of supply concerns, the EU should work on two distinct scenarios: A total cut in Russian deliveries (source disruption) and disruptions attributable to transit countries (transit disruptions), i.e. Ukraine or Belarus. Thus, reducing the overall dependence on Russian supplies and/or on instable transit routes are concurrent policy objectives of the EU if resilience towards disruptions in the supply is to be handled beyond storage capabilities of the Union.

Facing reduced domestic production, desire to reduce dependency on Moscow, limited prospects for EU shale gas and increasing concerns on the sustainability in North African supplies, developing alternative gas routes to Europe has become increasingly important. Significant efforts were made in 2015 to promote the development of the "Southern Gas Corridor" and to increase supplies from countries in the Caspian, as borne out by the Ashgabat declaration signed in May 2015 between Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Turkey and the EU. The "Southern Corridor" projects will pipe natural gas from Azerbaijan (10 bcm to the EU via the Trans-Adriatic pipeline, as of 2018). In the long term, the corridor could transport important resources from Turkmenistan, Iran and Iraq.

In sum, although EU-wide gas demand has been stagnant for the last decade, non-Russian supplies are still policy priorities for EU policy-makers.

3. Turkish gas market

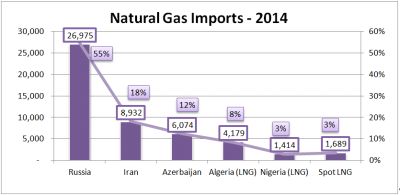

In addition to the EU, Turkey also has a huge natural gas market consuming around 50 bcm annually. In 2014, 49.2 bcm gas was imported by 9 pipe-gas and 2 LNG import license holders. Natural gas imports increased almost 9% compared to 2013. Around 55% of the imported gas was originated from Russia in 2014. National gas consumption in 2014 was almost 49 bcm.4

The consumption in Turkey is roughly divided into power generation (around 50%), industrial (25%) and household (25%). Disruptions in supply routes, limited storage capabilities and the most recent tensions with Russia once again highlighted the concerns over security of supply and immediate announcements were made from first hand government officials to accelerate the construction of the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP)5 and signing a MoU with Qatar to buy Qatari LNG and build a regasification terminal in Turkey additional to the two existing.6

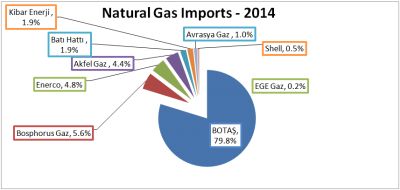

However, the gas import regime in Turkey is yet to be fully liberalized. The state-owned conglomerate Petroleum Pipeline Corporation (BOTAS) still dominates the imports into the country and the domestic wholesale market. 80% of the total imports are still being made by BOTAS, and in the wholesale market 80% of the total sales belong to BOTAS.

In particular, imports from countries where BOTAS has an existing contract are not allowed according to the Natural Gas Market Law. Given that BOTAS has imports contracts with Russian Federation, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Iran, no private parties can conclude import contracts with these countries. For other resource-holder countries, imports are not disallowed completely but subject to BOTAS's approval in order to avoid distressing BOTAS technically and financially. More specifically, Energy Market Regulatory Authority (EMRA) Board Decision No: 725 stipulates that the license applications will be directly rejected if BOTAS states that the responsibilities of BOTAS related to its existing contracts and export connections will be thwarted or serious economic and financial difficulties will emerge as a result of the proposed import.7 There is only one pipe-gas license that has been granted by EMRA other than companies who took over contracts of BOTAS partially or renewed those that had expired.8

In sum, imports into Turkey are still quite problematic and far from being fully liberalized. However, new legislation has been drafted by the Ministry and expected to come online soon. As such, the imports are expected to be fully liberalized and private parties will be able to participate in natural gas imports from third countries through bilateral contracts freely negotiated with their counterparts.

4. Israeli Gas: alternatives for Israel vs. alternatives for Turkey

4.1 Alternatives for Israel

Given the volume of the domestic market, Israel needs to sell the future production of its gas deposits in Leviathan field. After Italian Eni found huge reserves in Egypt, the only viable options for Israel turned out to be connecting its reserves with Anatolia and getting access to the European market or sending gas directly to Europe through the Mediterranean in the form of LNG. Although Jordan might seem as another option, it is far from absorbing the Israeli supplies.

From an economic and business perspective, Jordan is clearly an appropriate market for Israeli gas. Pipeline distances are short; potential linkages between the Israeli pipeline network and Jordan's are measured in mere tens of kilometers. The largest prospective customer, Jordan's National Electric Power Company (NEPCO), is a reliable partner with a reputation for ensuring its customers pay their bills.

In September 2014, the Leviathan partnership signed a letter of intent for the supply of gas to NEPCO - 45 BCM of gas over 15 years. The contract is estimated at more than US$15 billion, but the debate about the gas plan, which has continued for nearly a year already, has stalled the negotiations between the two countries.9

However, this phenomenon is overshadowed by the political risks. According to the Marshall Fund, the difficulty in signing a final contract is due to two main problems: Regulations in Israel and poor relations between Israel and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. "Regulatory uncertainty in Israel has delayed the development of Leviathan and the expansion of Tamar. Meanwhile the political climate affecting relations between Israel and Jordan has deteriorated."10

Feasible but restrained by political realities, Jordanian demand is not enough to absorb the Israeli gas resources even contract with NEPCO is realized. Other markets are needed to monetize Israeli gas deposits.

One option is exporting Israeli gas in the LNG form either through the existing LNG facilities in Egypt or through new facilities to be built in Cyprus. Given that, reserves have also been discovered in the EEZ of Cyprus, namely Aphrodite field, cooperation between Cyprus and Israel in gas exports might be an inevitable conclusion. The fact that the principal explorer and operator in the Israeli and Cypriot EEZs are the same US company, Noble Energy, may push towards cooperation between the two countries.

The Financial Times reported in December 8, 2015 that Yuval Steinitz, Israel's Minister of Energy, said the country was eyeing other export options for its gas including Jordan, Greece, Turkey and Western Europe. Turkey's recent estrangement with Russia, its biggest gas supplier, has revived hopes in Israel that the huge Turkish market could open up to Israeli gas, despite political rancor between the two countries.11

Tensions with Russia led Turkish policymakers to explore alternative gas supplies to get prepared for possible disruptions in the gas flow from Russia. Israel and Turkey have reached agreement on a political reconciliation that will end a five-year diplomatic estrangement and pave the way for talks on an undersea pipeline to export Israeli gas to the Turkish market. Benjamin Netanyahu's Israeli government confirmed the outlines of the deal, a day after Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey's president, signaled that the two countries were ready to normalize relations if they could agree on compensation for a deadly Israeli raid on a Turkish aid flotilla in 2010.12 "Senior government officials in Israel said on Thursday evening that Yossi Cohen, Mr Netanyahu's security adviser, and Joseph Ciechanover, an Israeli envoy to Turkey, had met Feridun Sinirlioglu, from the Turkish foreign ministry, in Switzerland and negotiated the principles of the agreement," The Financial Times reported.

Indeed, relations between Israel and Turkey have long been friendly since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Turkey was one of the earliest countries to establish diplomatic relations with Israel, and the relations boosted during the 1990s. Since the flotilla incidence, however, the relations had been at the lowest diplomatic level.

The Financial Times reported in December 17 2015 that Israeli officials also said that deliberations on laying a gas pipeline from Israel to Turkey and the selling of gas would begin "in the near future." Most recently, Israeli energy minister Yuval Steinitz stated that while Turkey and Greece are two options for Israeli gas exports, the latter is less-costly.13

Turkey can serve Israel not only as a cash-paying reliable market but also as a transit through European markets. As discussed above, Turkey has a huge and growing gas market supplied by several sources. Soon after the bomber shot-down incidence, Turkey quickly realized how dependent and vulnerable its gas market is to Russia and any disruptions in gas flows from Russia.

4.2 Alternatives for Turkey

Although alternatives do exist for Turkey, Turkey's gas strategy has been built on going beyond being a transit country and becoming a gas hub thus almost all international energy projects that would eventually add its mentioned position are being embraced by Turkey.

A particular interest has been shown by Turkish private gas sector for importing Israeli gas into the country. Corporate groups active in Turkish energy market have stated their interest in importing Israeli gas at the highest level. The head of Turkerler Holding Kazım Turker stated in a press interview that they are "actively involved in Turkish energy market and Iraqi upstream gas business and want to import 10 bcm/year gas from Israeli Leviathan gas field."14 Batu Aksoy from Turcas Petrol, on the other hand, stated that "bringing Israeli gas to Turkey is currently the most feasible energy project in the Mediterranean basin" and highlighted the "Israeli side's flexibility on the re-export clauses prevalent in most of the gas contracts." He anticipated US$1-3 billion to bring the gas from Leviathan to Turkey through a 500 km off-shore pipeline and expressed his companies in realizing such a project.15

Zorlu Group who also has gas-fired power plant projects in Israel is among the interested private parties. Zorlu most recently concluded a private deal for 6 bcm over 18 years with the project companies to purchase gas for its gas fired plants in Israel.16

It was also leaked to the press that project company Nobel and Delek contacted four Turkish energy companies - Zorlu, Turcas, Çalık and Enka- and asked for their preliminary evaluation in importing the gas to Turkey.17 Enka has gas fired plants in Turkey operating on build-own basis for which gas purchase and power sales contracts will be expiring one by one in the upcoming years.

Needless to say, companies other than the above mentioned also have an interest in the project. In a liberalizing gas market and liberalized power market such as Turkey, it is more than understandable that companies seek to secure their own supplies through privately concluded deals. Given the volume of the investment needed and the number of parties involved, a Turkish consortium including state-owned gas company BOTAS might turn out to be an optimal option to conclude the deal with the project developers.

5. Conclusion

Despite regulatory debates and uncertainties prevailing in Israel about the development of the Leviathan gas field, Prime Minister Netanyahu seems very unwilling to accept the fact that gas politics which is a national security matter is overshadowed by anti-trust concerns.

At the end of the day, gas is there and, in a way, it should flow to the markets. Given the historical détente between Israel and Turkey, the volume and structure of the Turkish gas market, its transit position through Europe and its vicinity to the gas deposits, Turkey turns out to be the optimal export route for Israeli gas reserves.

Meanwhile, the draft legislation to amend the existing Natural Gas Market Law is yet to reach the general assembly in the Turkish Parliament. It is expected that the amendments will further liberalize the gas market, and exports and imports will be totally liberalized.

The craggy aspect of Turkish option lies in the historical dispute on the island of Cyprus between Turkey and Greece. Any pipeline passing through the EEZ of Southern Cyprus (which was declared unilaterally by the Southern Cyprus) might be an international issue, and a potential Israel-Turkey pipeline would need to pass through Cyprus' EEZ to reach Turkey. Natural gas export options are also affected by disputes over the control of offshore resources, which need to be resolved via negotiation within the framework of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). The route of any oil or gas pipeline that passes through the EEZ of a country needs the approval of the coastal state. This effectively gives it a veto over such projects. The Eastern Mediterranean region presents a number of problems in terms of diplomatic recognition, adherence to UNCLOS, and agreed maritime boundaries. Turkey does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus, the 2007 maritime boundary agreed between Cyprus and Lebanon, or the 2010 maritime boundary between Cyprus and Israel. Turkey argues that Cyprus should be considered as an island with no rights to an EEZ beyond its 12 nautical mile territorial limit. No country other than Turkey recognizes the "Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus" (TRNC). For its part, the TRNC administration has assigned areas to the north, east and south of the island to Turkey's state-owned Turkish National Oil Company for offshore exploration. Two of these offshore blocks are areas that the Republic of Cyprus regards as within its EEZ. The area to the west of Cyprus is also problematic. Cyprus and Egypt signed a maritime boundary agreement in 2003. Turkey asserts a right to an EEZ border with Egypt, which would conflict with this. Additionally, Turkey does not recognize the right of Cyprus to have an EEZ beyond 12 nautical miles to the west of the island. Turkey's sensitivity to the rights of islands stems from Greek claims in the Aegean Sea, where most of the islands are part of Greece. Such differences may affect possible routes for undersea pipelines or power cables between Cyprus and Greece.18

Given these restraints, negotiations to settle the major dispute in the East Mediterranean re-gained momentum soon after the gas discoveries have proved to be commercially feasible. In this regard, negotiations between Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots for the solution of the 40+ year-old Cyprus problem may come to a reasonable solution in 2016. Thanks to the gas discoveries and the pipeline projects, it is reasonable to argue that the dispute is closer to a settlement now ever than before.

The gas discoveries may or may not alleviate the tensions between countries, but one thing prevails - that the huge gas reserves are needed in the developed and developing economies especially after the COP21 Paris agreement in which countries promised to reduce the usage of coal as a source of energy.

Footnotes

2. Marie-Claire Aoun, Sylvie Cornot-Gandolphe, "The European Gas Market Looking for its Golden Age?" The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri), October 2015, p.9.

3. Dave Jones, Manon Dufour, Jonathan Gaventa, "Europe's Declining Gas Demand: Trends and Facts on European Gas Consumption", E3G, June 2015.

4. "Natural Gas Market Report-2014", EMRA.

6. http://www.lngworldnews.com/report-turkey-agrees-lng-import-deal-with-qatar/

7. EMRA Board Decision 725, 13.04.2006, Article 3.

8. The benefeciary of the license is Siyahkalem, and the origin of the proposed project is Iraq. The contractual relationship between the company and the Iraqi side (Iraqi governemnet or KRG) is quite controversial.

9. http://www.globes.co.il/en/article-importing-israeli-gas-jordans-best-option-report-1001082321, Note that 45 bcm in 45 years corresponds 3 bcm annual deliveries.

10. Simon Henderson, "ibid", p.9.

11. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/1fa1f05e-9dc0-11e5-8ce1-f6219b685d74.html

12. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/4a3d52da-a500-11e5-a91e-162b86790c58.html#axzz3z8DWWaCX

13. http://www.yenisafak.com/en/economy/israel-wants-to-export-gas-via-turkey-steinitz-2398655

14. http://www.dunya.com/sirketler/turkerler-holding-de-israil-gazi-icin-hazir-286015h.htm

15. http://www.sabah.com.tr/ekonomi/2015/12/22/ozel-sektor-israil-gazina-talip

17. http://www.haberturk.com/ekonomi/enerji/haber/917577-israil-gaz-icin-4-turk-devini-istiyor

18. Simon Henderson, "ibid", p.6.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.