A number of important changes in Public Procurement Law in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland came into force in 2010.

Introduction

These spring mainly from the new 'Procurement Remedies Directive' 2007/66/EC which was required to be transposed into national law by 20 December 2009. That date was met in Northern Ireland where the Public Contracts (Amendment) Regulations 2009 and the Utilities Contracts (Amendment) Regulations 2009 were both published in November 2009. In the Republic of Ireland, the European Communities (Public Authorities Contracts) (Review Procedures) Regulations 2010, and the European Communities (Award of Contracts by Utility Undertakings) (Review Procedures) Regulations 2010 were both made by the Minister for Finance for the same purpose on 25 March 2010.

The new 'Remedies' regime is intended to improve the effectiveness of those procedures governing the judicial review of contracts awarded by public authorities and regulated utilities (to which existing procurement laws apply) and introduce a greater level of consistency between the laws of Member States in this regard.

Although the need for greater commonality of remedies is desirable, a certain amount of discretion was afforded to Member States to implement the new rules as they saw fit in their own jurisdictions and hence there are still some differences between national laws on the subject.

One particularly important difference between the new Regulations in the Republic of Ireland and those in Northern Ireland (and England and Wales) is that in the Republic of Ireland, the new laws apply to "decisions taken, after the coming into operation of [the Regulations], by contracting authorities in relation to the award of reviewable public contracts, regardless of when the relevant contract award procedure commenced", whereas the new legislation in Northern Ireland provides that nothing therein "affects any contract award procedure commenced before 20 December 2009". Thus, in the Republic, the new Remedies Regulations apply to any decisions taken on or after 20 December 2009 in relation to a contract award procedure commenced before, on or after 20 December 2009, whereas in Northern Ireland the new Regulations only apply where a contract award procedure has commenced on or after 20 December 2009.

The main features of the new 'Remedies' regime are:

- the creation of a new legal remedy of 'ineffectiveness' for the most serious breaches of Procurement Law. Previously, in circumstances where an awarding authority had entered into a contract, an aggrieved tenderer alleging a breach of the procurement rules was limited to seeking an award of damages or injunctive relief (or, in certain circumstances, a declaration of voidness at the discretion of the Court). Under the new Regulations, the Courts, for the first time, are required to declare concluded contracts to be ineffective (from the date of such declaration) where certain serious breaches are found to have occurred. This is a mandatory remedy, save in exceptional cases where alternative sanctions or penalties may be applied by the Court;

- enhanced provisions in relation to the 'standstill period' including a preclusion on concluding a contract during that period and the possible availability of the remedy of ineffectiveness if the contract is concluded during that period;

- important changes to rules on the information to be dis seminated (and how that should be effected) to candi dates (at pre-qualification stage) and tenderers (post- qualification) including in relation to de-briefing;

- a requirement for notification of reasons at the date of notifying either a decision to eliminate a candidate or the decision to award a contract (preceding the stand still period);

- the automatic suspension of the contract award procedure when an unsuccessful candidate or tenderer initiates a High Court challenge in relation to that procedure. The new Regulations prescribe that the contracting or awarding authority will be precluded from concluding a contract until the High Court has made a decision on the application either for interim measures or judicial review or until the Court has lifted the suspension at its discretion;

- the possibility of other remedies being imposed by the Courts for serious breaches of procurement law (e.g. financial penalties and contract shortening); and

- important changes to time limits for notices and for initiating legal proceedings (now to be considered in the light of two decisions by the Court of Justice of the European Union on 28 January 2010).

The Remedy of Ineffectiveness

The new laws have introduced the possibility of aggrieved tenderers applying to the Courts for a declaration that a concluded contract is ineffective. This is a radical change. Previously, once a contract had been concluded, the remedy generally available to a complainant was an award of damages and/or, in appropriate cases, injunctive relief (although in certain circumstances there could also be a declaration of voidness at the discretion of the Court).

Clearly, a declaration of ineffectiveness is a severe consequence for both the awarding authority and the successful tenderer, and any possibility of such a declaration being made will lead to some uncertainty, even after contract award. However, this remedy is only mandatory in situations where the most serious breaches of Procurement Law have occurred.

It is also important to point out that any ineffectiveness is prospective, meaning that it applies only to obligations that have yet to be performed under the contract. Obligations that have arisen prior to the declaration need not necessarily be affected.

Unless, in the Court's opinion, there are overriding reasons relating to a general interest which require a contract to be maintained in place, a declaration of ineffectiveness (i.e. a mandatory order of voidness) may be obtainable where any of the following circumstances arise:

'Illegal direct awards'

An illegal direct award is where a contract has been entered into in circumstances where no contract notice has been published in the Official Journal of the European Union (OJEU) contrary to the requirements of EU law.

This can arise, for example, where an awarding authority has mistakenly relied upon an exemption from the requirement to publish a contract notice or wrongly considered that the contract in question was outside the scope of the applicable Regulations.

Other examples where an illegal direct award could be made are where the contract entered into is outside the scope of any contract notice that has been published or a drawdown contract or mini-competition fell outside the scope of a framework agreement, or where a variation is made to a contract in the erroneous belief that the scope and scale of the change is within the scope of the contract notice previously published in connection with that contract.

Breach of 'Standstill Period' and Substantive Procurement Law

The ineffectiveness remedy is also available where there has been non-compliance with the 'standstill period' rules (see below) combined with a breach of substantive Procurement Law which has affected the chances of the applicant candidate/tenderer obtaining the contract.

If an awarding authority fails to respect an unsuccessful tenderer's entitlements to information about the award process and subsequently awards a contract, or that authority enters a contract before the standstill period has expired or following the commencement of legal proceedings, and that bidder has a valid complaint about a breach of substantive procurement law (e.g. the non-disclosure of award criteria), then the Courts must ordinarily declare any signed contract to be ineffective.

Other Remedies

In Northern Ireland, where a Court declares a contract to be ineffective, it must also order a financial penalty to be imposed on the awarding authority.

In addition, in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, where the grounds for ineffectiveness are satisfied but the Court nevertheless determines that there is an 'overriding reason in the general interest' to allow the contract to continue, the Courts must impose a financial penalty and/or order for the shortening or (in RoI) termination of the contract.

In the Republic of Ireland, financial penalties can amount to up to 10% of the contract value. No such limits apply in Northern Ireland. However, in both jurisdictions, the financial penalties are required to be "effective, proportionate and dissuasive", reflecting the wording of the 2007 Directive.

Automatic suspension

Previously, unsuccessful tenderers were obliged to apply to the Courts for injunctive relief in circumstances where they felt aggrieved by the conduct of the procurement process and wished to prevent a contracting authority from entering into a contract following the expiry of the standstill period.

Under the new laws, awarding authorities are now automatically obliged to refrain from entering into a contract from the point at which legal proceedings are commenced. An injunction is no longer necessary to prevent the contract from being signed.

The automatic suspension shall remain in force unless it is lifted by order of the Court or the legal proceedings are discontinued.

'Standstill Periods' and Information Entitlements/Obligations

The 'standstill period' is the period which follows the notification to bidders of the awarding authority's decision to award a contract and during which unsuccessful tenderers can review the decision before the contract is concluded. The standstill period has been important for some years following the Alcatel decision but under the new regime its significance is even greater. Any failure to comply with the rules governing the standstill period may now leave the awarding authority open to an ineffectiveness claim.

There are a number of aspects of the standstill period that need to be considered carefully in order to ensure compliance:

Timing

Under the new Regulations, in the Republic of Ireland, the prescribed standstill (or 'Alcatel') period begins on the day after the day on which each candidate (i.e. an economic operator which applied to be selected to tender or negotiate a contract) and each tenderer concerned is sent a notice of the intention to make the contract award decision (a "standstill notice") and must:

- if sent by electronic means or fax, continue for at least 14 calendar days, or

- if sent by any other means, continue for at least 16 calendar days.

In Northern Ireland, the standstill period commences on the date on which a valid standstill notice is sent to the relevant tenderers (and candidates) and:

- if a notice is sent by a fax or electronic means, the standstill period shall end at midnight at the end of the 10th day after the relevant sending date; or

- if sent by other means, the standstill period shall end at whichever the following occurs first:

- midnight at the end of the 15th day after the relevant sending date; or

- midnight at the end of the 10th day after the date on which the last of the recipients receives it.

A statement of when the standstill period ends has to be included in the standstill notice.

Information

Under the new regime, there is an obligation on awarding authorities to fast-forward the provision to tenderers (or candidates who have not previously been notified) of information to which they might otherwise have been entitled if they had requested a debrief or exercised their rights in relation to the obtaining of information after an award had been made. In other words, the reasons (in Northern Ireland) or a summary of the reasons (in the Republic of Ireland) for the contract award decision must now be communicated to remaining candidates and tenderers at the commencement of the standstill period, rather than, as was previously the case, upon request. Under the new rules, the information should essentially be furnished automatically and this should take place as soon as possible after the contract award decision has been made.

The standstill notice must be sufficient to enable the recipient to make an informed decision whether or not to seek review of the awarding authority's decision. In the Republic of Ireland, the Regulations specifically provide that the notice shall:

- inform the tenderers (and candidates) concerned of the decision reached concerning the award of the contract;

- state the exact standstill period applicable;

- include:

- in the case of an unsuccessful candidate, a summary of the reasons for the rejection of his or her application; and

- in the case of an unsuccessful tenderer, a summary of the reasons for the rejection of his or her tender including a statement of the characteristics and relative advantages of the tender selected.

In the case of an unsuccessful candidate, the information may, according to the Regulations, be provided by setting out:

- the score obtained by the candidate concerned; and

- the score achieved by the lowest scoring candidate who was considered to meet the prequalification requirements, in respect of each criterion assessed by the contracting authority.

In the case of an unsuccessful tenderer, the information may, according to the Regulations, be provided by setting out:

- the score obtained by the unsuccessful tenderer concerned; and

- the score obtained by the successful tenderer, in respect of each criterion assessed by the contracting authority.

In the case of a framework agreement, the information obligation may, according to the Regulations, be satisfied by setting out:

- the scores obtained by the tenderer concerned in respect of each criterion assessed; and

- the scores obtained in respect of each criterion assessed by the contracting authority by the lowest scoring tenderer who was admitted to the framework.

In Northern Ireland, the new Regulations require the standstill notice sent to tenderers to include the following:

- the criteria for the award of the contract;

- the name of the successful tenderer;

- the reasons for the decision, including:

- the characteristics and relative advantages of the successful tender;

- the scores (if any) obtained by the recipient of the notice and by the successful tenderer; and

- the reasons why the technical specification were not met; and

- a precise statement of when the standstill period is expected to end (and, if relevant, how its ending may be affected by any other contingencies) or the date before which the authority will not enter into a contract or framework agreement.

When the award notice is sent to candidates, it should include essentially the same information including the reasons it was not successful, but not the 'relative advantages' of the successful tender.

Time Limits for Commencing Review Proceedings

Republic of Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland, Judicial Review proceedings (the remedy ordinarily available) under Order 84A of the Rules of the Superior Courts seeking either interim or interlocutory orders or in respect of a challenge to a contract award must now be brought within 30 calendar days after the applicant was notified of the decision or knew, or ought to have known, of the infringement alleged in the application. This is a major change from the former limit of three months, subject to acting at the earliest opportunity. This is now reflected in the new Order 84A of the Rules of the Superior Courts issued in September 2010.

Furthermore, an application for a declaration that a contract is ineffective shall be made within 30 calendar days in circumstances where the applicant would ordinarily be on notice in the following circumstances set out in the Regulations:

- where the contracting or awarding authority has published an award notice or, in the case of a contract awarded without prior publication of a contract notice, on condition that the contract award notice sets out the justification of the contract decision not to publish a contract notice;

- where the contracting authority notified each tenderer or candidate concerned of the outcome of his or her tender or application and that notice contained a summary of the relevant reasons that comply with the Regulations; or

- in cases where a contract based on a framework agreement and of a specific contract based on a dynamic purchasing system where the contracting authority has given notice in accordance with the Regulations to unsuccessful tenderers and candidates.

In all other cases where ineffectiveness is sought, application shall be made within six months after conclusion of the relevant contract.

The new Regulations in the Republic of Ireland further provide expressly that an eligible person may apply to the Court for interlocutory orders with the aim of correcting an alleged infringement or preventing further damage to that person's interests including measures to suspend or to ensure the suspension of the procedure for the award of the contract concerned and the implementation of any decision taken by the contracting authority for review of the contracting authority's decision to award the contract to a particular tenderer or candidate and that such application shall again be made within 30 calendar days after the applicant was informed of the circumstances or ought to have known of them.

The making of specific provision for interim or interlocutory relief and the removal of the obligation to act "promptly" or "at the earliest opportunity" (deemed too vague) attempts to cure the defaults in the Irish regime which formed the basis of the judgments of the Court of Justice of the EU in Luxembourg in European Commission v Ireland1 on 28 January 2010 and the parallel case on the same date concerning the UK in Uniplex2.

A person intending to make an application to the High Court in the Republic of Ireland shall first notify the contracting authority in writing of:

- the alleged infringement;

- his or her intention to make an application to the Court; and

- matters set out which in his or her opinion constitute the infringement.

The High Court may:

- set aside, vary or affirm a decision to which the Regulations apply;

- declare a contract ineffective;

- impose alternative penalties on a contracting authority, and make any necessary consequential order;

- make interlocutory orders with the aim of correcting an alleged infringement or preventing further damage to the interests concerned, including measures to suspend or to ensure the suspension of the procedure for the award of the contract or the implementation of a decision of the contracting authority;

- set aside any discriminatory technical, economic or financial specification in an invitation to tender, contract document or other document relating to a contract award procedure;

- when considering whether to make an interim or interlocutory order, take into account the probable consequences of interim measures for all interests likely to be harmed, as well as the public interest, and may decide not to make sure an order where its negative consequences could exceed its benefits; and

- order suspension of the operation of a decision or a contract and may also award damages as compensation for loss resulting from a decision that is in breach of the Law of the European Union or of the European Communities or the law of the State transposing such law.

The Rules of the Superior Courts (Order 84A) were amended in September 2010 to reflect the above and including by deletion of the requirement that application under the Rules be made to the Court "at the earliest opportunity" in order to comply with the European Commission v Ireland and Uniplex cases (see below).

Northern Ireland

As in the Republic of Ireland, the new Regulations require proceedings to be brought within a set time limit.

It was previously the case that proceedings had to be brought 'promptly and in any event within three months' from the date when the grounds for the bringing of those proceedings first arose, unless the Court considered that there was good reason for extending such a period. In general, this three month time limit remains relevant where remedies other than ineffectiveness are sought. However, in light of the recent judgments in the cases of the European Commission v Ireland and Uniplex (see below), it is expected that the Regulations will be amended to remove the requirement that proceedings be brought 'promptly' in early/mid 2011.

Where ineffectiveness is sought as a remedy, proceedings can generally be brought within six months of the contract award. However, awarding authorities can reduce this period to 30 days by publicising the contract award. Where a contract has been previously publicised by a contract notice in the OJEU, the 30 day period will apply where tenderers and candidates are informed of the concluding of the contract and provided a summary of the reasons for the decision. Where there has not previously been a contract notice published in the OJEU, the 30 day limit also applies where a contract award notice is published setting out justification as to why no contract notice was published in the first place.

Judgments of Court of Justice of the European Union - Time Limits

Two important Judgments were handed down by the Court of Justice of the European Union on 28 January 2010. Both of these cases concerned the implementation at national level in Ireland and the UK of time limits for the bringing of challenge by way of judicial review proceedings to decisions concerning Public Procurement. They have profound implications.

So far as possible, the Republic of Ireland, which was late in making the Regulations to transpose the new Remedies Directive, has attempted to take cognizance of those decisions in the new Regulations made in March 2010 and Order 84A of the Rules of the Superior Courts was also amended in September 2010. The new Regulations applicable in Northern Ireland are expected to be amended accordingly in early/mid 2011.

In European Commission v Ireland the background was that the National Roads Authority (NRA), in the course of conducting the procurement over the M1 Dundalk Western Bypass Motorway, by letter dated 14 October 2003 informed the two shortlisted consortia, Celtic Roads Group (CRG) and Eurolink that, following submission of "best and final offers" (BAFOs), CRG had been chosen as the preferred tenderer. The letter also stated that the bid by Eurolink was not being rejected and that the NRA reserved the right to re-enter negotiations with Eurolink if negotiations did not conclude satisfactorily with CRG. NRA subsequently awarded the contract to CRG in December 2003. SIAC, a member of the Eurolink consortium, challenged the award by way of application for Judicial Review in the Irish Courts but the action was dismissed as being out of time. The High Court held that the three month outer time limit for challenges (the requirement was to bring such a challenge "at the earliest opportunity and in any event within three months from the date when grounds for the application first arose..." unless the Court considers that there is "good reason" for extending such period) had started running when Eurolink received the NRA letter of 14 October 2003. The European Commission then brought an action claiming that Ireland had failed to fulfil its obligations under the existing Public Sector Remedies Directive 89/665/ EEC by failing to:

- notify a tenderer that its bid had been rejected; and

- transpose properly the rules relating to time limits.

In her Advisory Opinion, Advocate General Kokott had opined that the Court ought to uphold both limbs of the Commission's complaint. She recommended that the Court decide that Ireland had failed in its duty to provide effective legal protection for Eurolink by not formally informing it of the rejection of its bid and she submitted that Ireland's contention that publication of an award notice in OJEU satisfied this was insufficient as being simply a notice to the public and not a notification to Eurolink in particular.

As to the time limits, Advocate General Kokott was of the view that the rule cited in brackets above, was not clearly on its face applicable to interim decisions such as that contained in the NRA letter of 14 October 2003 and she recommended rejection of Ireland's submission that its common law system allowed its judges to apply the limitation period, by analogy, to such interim decisions.

The Court of Justice of the European Union followed the Opinion of Advocate General Kokott entirely and, thus, the European Commission succeeded in its proceedings against Ireland.

In a case containing similar issues on the same date, Uniplex (UK) Limited v NHS Business Services Authority, Advocate General Kokott had opined that a limitation period in relation to a declaration for infringement of Public Procurement Law and action for damages only began to run when the applicant knew or ought to have known of the alleged infringement. She was of the view that a limitation provision which allowed a national court discretion to dismiss an application for a declaration of infringement and actions for damages as inadmissible solely by reference to a requirement to bring proceedings 'promptly' was incompatible with EU Law. The Court accepted and applied the Opinion of the Advocate-General.

The new Irish Regulations of 25 March 2010 attempt to recognise the effect of these decisions including by making specific provision as follows:

(i) the requirement in the Irish Regulations for initiating proceedings "at the earliest opportunity" has been removed (and a similar amendment was made also to Order 84A in September 2010);

(ii) time is now deemed to run from when an applicant knew or ought to have known of the circumstances giving rise to the cause of action or complaint; and

(iii) similar express provisions are made in respect of time running for purposes of applications for interim measures or interlocutory orders.

It is likely that the Regulations applicable in Northern Ireland will also be amended in the near future to reflect those judgments. A UK Cabinet Office consultation on the topic concluded in late January 2011.

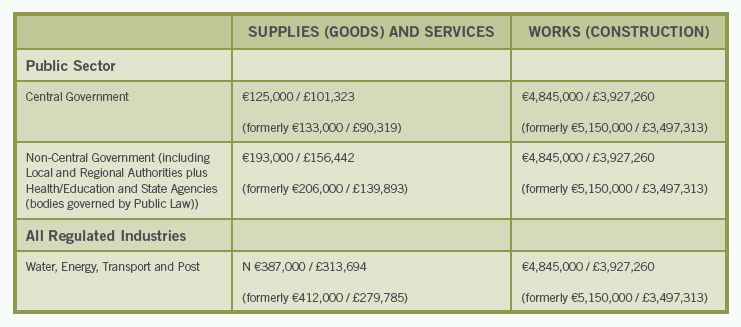

New EU Financial Thresholds

The European Commission revises the financial thresholds in the Public Sector and Utilities Directives every two years in order to take account of changing currency values.

By Regulation 1177/2009/EC of 30 November 2009, the Commission determined that the following are to be the values from 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2011 inclusive. For your information, we have set out the new thresholds below and to aid comparison, we have provided the figures which obtained from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2009 (specified in brackets below).

Footnotes

1. Case C-456/08 European Commission v Ireland, 28 January 2010

2. Case C-406/08 Uniplex (UK) Ltd v NHS Business Services Authority, 28 January 2010

This article contains a general summary of developments and is not a complete or definitive statement of the law. Specific legal advice should be obtained where appropriate.