On April 11, 2017 the Federal Court of Appeal released its decision in BMS' appeal from a Judgment of the Federal Court that had dismissed BMS' prohibition application relating to the drug atazanavir and Canadian Patent No. 2,317,736 (see the Federal Court's Judgment here). The decision significantly clarifies many aspects of the law of obviousness after the Supreme Court of Canada's seminal 2008 decision in Plavix 1 (see our companion post here).

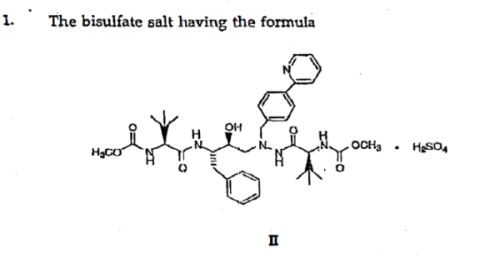

The 736 Patent is generally directed to a crystalline salt of atazanavir bisulfate. Claim 1 of the 736 Patent provides:

The Applications Judge had concluded that the inventive concept of the 736 Patent "includes the salt's anhydrous crystalline solid form and its solid-state physical stability." Although it was agreed that the skilled person could not predict the anhydrous solid form or the physical stability of the claimed salt, the Applications Judge nonetheless held that the claims were obvious in light of the prior art.

On appeal, the Court of Appeal concluded that the Application Judge had erred in her assessment of the inventive concept, holding that the inventive concept is not materially different from the solution taught by the patent. Here, the low solubility of atazanavir free base was the motivation to pursue the subject matter ultimately described and claimed by the 736 Patent and the inventive concept was limited to the bisulfate salt of atazanavir, which has equal or better bioavailability than atazanavir free base:

[75] For the reasons set out above, I find that the "inventive concept" is not materially different from "the solution taught by the patent". Had the Federal Court applied that definition to the facts, it would have found that the inventive concept in this case is atazanavir bisulfate, a salt of atazanavir which is pharmaceutically acceptable because it has equal or better bioavailability than the atazanavir free base. Atazanavir's limited bioavailability was the source of the motivation to pursue the solution. The fact that claim 2 of the '736 patent claims a pharmaceutical dosage form of Type-I atazanavir bisulfate confirms its acceptability for pharmaceutical purposes.

Had the Applications Judge applied the proper inventive concept, it would not have been necessary to even consider "obvious to try", as there was no difference between the prior art and the inventive concept of the 736 Patent. Any distance between the two could be bridged by the skilled person without inventive ingenuity:

[82] On the facts of this case, it seems to me that the facts which support the conclusion that the distance between the prior art and the inventive concept (defined as the solution taught by the patent) could be bridged without recourse to inventiveness would also satisfy the first Lundbeck factor in that it was more or less self-evident that what was being tried ought to work. It seems to me that when this factor is taken it was articulated by the Supreme Court, the conclusion that the Skilled Person would have regarded a salt screen as a more or less self-evident way of getting to a form of atazanavir with greater bioavailability is inescapable.

A copy of the Court of Appeal's Reasons may be found here.

Teva was represented in the appeal by Aitken Klee partners Jon Stainsby and Scott Beeser.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.