Part I of this series of articles reviewed some of the basic tax requirements for using trusts to split income, Part II discussed a number of tax planning opportunities that can be accessible through the use of trusts, and Part III reviewed traditional testamentary trust income splitting planning and the upheaval to all testamentary trust (and lifetime trust) planning caused by the enactment of Bill C-43, Economic Action Plan 2014 Act, No. 2 ("Bill C-43"). In this the fourth and final instalment of the series, we'll review some of the benefits and risks of planning with trusts resident in Alberta ("Alberta Trusts") and with trusts deemed to be resident under subsection 94(1) of the Income Tax Act (Canada) (the "Act").1

Alberta Trust Planning

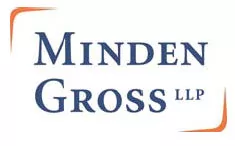

Most of us outside of Alberta look at Alberta tax rates with a combination of awe and wonder. In 2015 the top marginal combined federal and Alberta personal tax rates were as set out below:2

As a result, it is no surprise that many taxpayers and their advisers have been trying to find acceptable or at least creative ways to shift income from their client's jurisdiction of residence to Alberta for years. Out of this desire a fairly significant interprovincial tax planning sector formed, and many different strategies were generated to accomplish this objective, including strategies involving trusts created to be resident in Alberta for the benefit of residents of other provinces.

Although there are different ways to implement Alberta Trust structures, in general, the intention of using an Alberta Trust will be to have the income of the trust taxed in Alberta at low Alberta tax rates, and to then have capital distributed to non-Alberta resident beneficiaries who should generally not be subject to any additional tax on such capital distributions.

While Alberta Trusts and other interprovincial tax planning has made many clients happy, unfortunately, the other Canadian provinces losing tax base to Alberta have been less happy. The result has been considerable activity involving the tax authorities reviewing and sometimes challenging interprovincial tax plans.

To assist the tax authorities in their efforts to eliminate the benefits of interprovincial tax planning, including the use of Alberta Trusts, provincial legislators have introduced and enacted, sometimes retroactively, a number of provincial anti-avoidance rules, including provincial general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) provisions. New subsection 104(13.3) of Bill C-43 may also serve to dampen certain types of interprovincial planning strategies that rely on the making of designations under subsections 104(13.1) and (13.2).3

In addition, a number of court cases have been heard and have effectively shut down certain types of planning though not specifically Alberta Trust planning. For example, cases such as the Supreme Court of Canada's Garron4 decision, have caused tax advisers to closely monitor and sometimes adjust their trust plans, including with respect to Alberta Trusts, to ensure that the trusts are resident in Alberta and not elsewhere.

There are also other factors that are or may serve to continue to dampen such planning. For example, there is always the risk that another province outside of Alberta will reassess the Alberta Trust as being taxable in that province. If this were to occur then the income could be subject to double tax unless the matter can be resolved through recourse to the tax collection agreements among the provinces and federal governments. In addition, world events that are intended to limit shifting income between jurisdictions such as the OECD base erosion and profit shifting initiatives could eventually be applied in a domestic context.

Even with all of the risks and issues facing Alberta Trust planning it would appear that Alberta Trust planning continues to be implemented, and—given provincial tax disparities—it is no wonder.

Section 94 Deemed Resident Canadian Trusts

Trust Residency in Canada

Under Canadian taxation principles a trust can be a factual resident in Canada if, pursuant to common law principles, the location of "central management and control" of a trust—which is really a fancy way of saying where the real power to make trust decisions lies—is determined to be in Canada.5

While the location of central management and control of a trust will usually be determined by examining where the trustees make their decisions, the test is fact-based so that if the real decision-makers are not the trustees, then it will be the location of those persons that will determine the common law residence of the trust. In this regard, in Garron,6 the Supreme Court of Canada found that Mr. Garron, a Canadian resident, had too many powers and had de facto control of the trust, causing an otherwise offshore trust to be determined to be factually resident in Canada.

Putting factual Canadian resident situations like Garron aside, there continues to be a purely Canadian non-resident category of trust that can have Canadian resident beneficiaries where the trust has only been funded by non-residents of Canada.7 However, it is possible for these trusts to lose their non-resident status if they are deemed to be resident of Canada pursuant to section 94.

The recently amended provisions of section 948 are exceptionally broad and the purpose of the discussion that follows is merely to provide a flavor of just how expansive the amended rules are.

Even where a trust would not be a Canadian resident based on common law principles, with extremely limited exceptions, the rules in section 94 will deem such trusts to be resident in Canada if they have a "resident contributor". A resident contributor is a Canadian resident person, whether an individual, corporation or other entity, that, with limited exceptions, has made a direct or indirect transfer of property to the trust. Such a transfer is referred to as a contribution in section 94 and the scope of the possible types of indirect transfers that can be made to a trust is breathtaking.9 Furthermore, even if a contributor who was a Canadian resident ceases to exist, for example, on death, section 94 will still generally apply if the trust is considered to have a "resident beneficiary" because the trust has a Canadian resident beneficiary at any particular time.

One exception to these rules that previously was widely used was the so-called "immigrant trust exception". Unfortunately, this exception was eliminated as part of the legislative changes enacted in Bill C-43.10

Non-Tax Reasons to Create Non-Resident Trusts

Although there are many evils that the federal government has intended to stop through amendments to section 94, not all non-resident trusts ("NRTs") are evil. For example, a contributor might create an NRT from a desire to benefit non-residents. In addition, structuring a trust outside of Canada may enable the contributor to keep his or her affairs more private, allow for the trust to access investments that are unavailable to Canadian residents, and possibly allow the trust to be governed by more favourable trust and insolvency legislation, such as fraudulent conveyance and other legislation that might better enable the contributor to be assured that the trust property is protected and preserved for the benefit of the trust's beneficiaries.

A Modest Section 94 Trust Tax Benefit (Outside of Alberta)

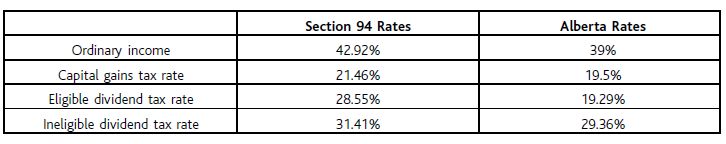

Interestingly, although there can be some tricks and traps for the unwary, the actual taxation of section 94 trusts will in many cases not be that different or that much more complicated than the taxation of ordinary resident Canadian trusts. In addition, as is shown in the chart below, in 2015 section 94 trusts are actually taxed quite favourably compared to the taxation of ordinary inter vivos Canadian trusts outside of Alberta.11

However, because of the even more favourable tax treatment afforded to Alberta trusts, and since administering section 94 trusts is generally a bit more complicated and costly than administering purely Canadian trusts, it appears somewhat unlikely that specific planning will be used to take advantage of these lower rates. Still, for taxpayers outside of Alberta who are using otherwise non-resident trusts and are caught by the section 94 deemed resident trust rules, the tax savings will likely be a pleasant surprise.

This article first appeared in the Wolters Kluwer newsletter The Estate Planner No. 245, dated June 2015.

Footnotes

1 Unless otherwise noted all statutory references are to the Act.

2 Even before the election of the NDP in Alberta, due to proposed tax rate changes in the 2015 Alberta Budget, tax rates were expected to be rising in Alberta beginning in 2016. Due to the change in government it may be a while before the Alberta tax situation becomes clear, though it is hard to imagine that there won't still be a significant continuing Alberta advantage even after all changes are fully phased in. In addition, due to proposed tax rate changes in the 2015 federal Budget, ineligible dividend tax rates are generally expected to increase (actual results may vary in specific provinces).

3 As was discussed in Parts II and III of this series of articles, the rules in subsections 104(13.1) and (13.2) can be used to designate amounts paid by a trust to a beneficiary as being taxable only in the trust, which could give rise to a number of income splitting benefits, including allowing designated amounts paid out to beneficiaries to still enjoy the testamentary trust's graduated tax rates. However, due to the enactment of Bill C-43, effective for the 2016 and subsequent taxation years, the ability to utilize the designations provided under these provisions will be restricted so that designations can only be made to permit trusts to use up losses. 4 Fundy Settlement v. The Queen, 2012 DTC 5063 (SCC).

5 For a more detailed review of trust residency issues in Canada see Michael H. Dolson, "Trust Residence After Garron: Provincial Considerations", (2014) vol. 62, no.3 CTJ.

6 Supra, note 4.

7 Sometimes these trusts are called "granny trusts" and other times "pure offshore trusts".

8 See Bill C-48, Technical Tax Amendments Act, 2012, which received royal assent on June 26, 2013.

9 See, in particular, the "arm's length transfer" definition in subsection 94(1) and the extended rules of application in subsection 94(2).

10 The extremely limited grandfathering provisions associated with these changes ceased to apply at the end of calendar 2014.

11 Supra, note 2.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.