An exerpt from Canadian Underwriter, February

2015.

Authored by

Timothy Zimmerman, Senior Manager, Litigation Accountaing and

Valuation, Collins Barrow.

A number of great articles have been written in the past dealing with depreciation as a saved expense in the context of fully destroyed and replaced assets; however, few have written about how to deal with depreciation savings for undamaged assets in a business interruption claim.

From an accounting perspective, it is generally quite clear that when an asset is destroyed as a result of a peril (i.e. fire or flood) the depreciation on that asset ceases which results in the depreciation expense being saved by the insured. However, what happens when an asset is not damaged? Should depreciation on those assets be considered a saved expense?

First, here is a quick overview of depreciation.

Depreciation is a noncash expense that is used to allocate the cost of an asset over its useful life because most assets lose their value over time and must be replaced once the end of their useful life is reached. There are four principal causes of depreciation:

- Functional depreciation (asset declines in productivity or service over time);

- Physical depreciation (asset deteriorates due to environmental factors over time);

- Technological depreciation (asset become obsolete from improved technology); and

- Economical depreciation (asset devalues due to economic factors).

Now, let's consider the following scenario:

The insured owns and operates a small stamping business with two major assets:

- An extravagant rotating sign out front of the business that says "Simon's Super Stamping". The sign has a useful life of 10 years based on the gradual deterioration from weather and the insured depreciates the sign using the straight line method1 and

- A stamping machine that has an estimated useful life of 100,000 stamped widgets. The insured depreciates the stamping machine using the units of production method2.

Assume a fire occurs at the Insured's premises and the building is destroyed, including the stamping machine, however the sign remains undamaged. As a result of the fire, the business is unable to operate in any capacity for 12 months.

It is clear that since the stamping machine was totally destroyed any depreciation that would have been incurred on the stamping machine would be saved. However, would it be appropriate to consider any depreciation saved on the undamaged sign?

Alternatively, what if an uncontrolled truck drove off the road, destroyed the sign and went through the building, but the stamping machine was undamaged. Since the sign was totally destroyed any depreciation on the sign would be saved, but would it be appropriate to consider any depreciation saved on the undamaged stamping machine?

In assessing whether depreciation is saved on an undamaged asset the key questions to ask are:

- What is the depreciation driver and method of depreciation?

- Has the useful life of the asset been extended as a result of the loss?

In the fire example above, the sign is being depreciated based

on its expected useful life of 10 years due to its gradual

deterioration from the environment. If the business

wasn't operating for 12 months the sign would continue to be

exposed to the same weather conditions and would need to be

replaced at the same time irrespective of whether the business was

operating. On this basis, it would not be fair to the insured

to calculate depreciation savings as there has not been an

extension to the useful life of the asset.

Conversely, if the stamping machine was not damaged by the rogue

truck piling into the building would the useful life of the asset

have been extended if the business was closed for 12 months?

Generally, the answer would be yes. The method of depreciation for

the stamping machine is the number of units produced, and if the

business ceased operating then no units would be produced. Further,

since the machine would be able to produce the lost units after the

business recommences, the useful life of the machine has

effectively been extended.

However, would the depreciation actually be saved?

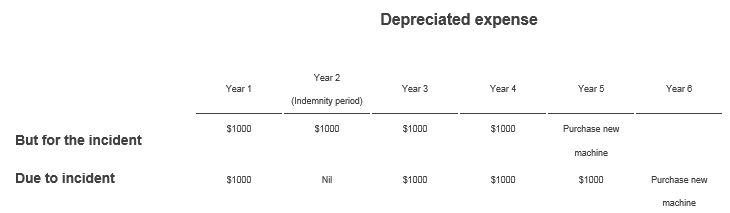

It has been argued that the actual depreciation savings takes place subsequent to the resumption of operations and the savings to the insured is the time value of money associated with the purchase or replacement of the machine in a future period. To illustrate this point, let's consider the following example:

- Machine purchased Year 1 (at cost): $4,000

- Depreciation method: Units of production

- Average units produced annually: 1,000

- Total life in number of units: 4,000

- Salvage value: nil

In the example above, although depreciation is not incurred in the year of the Incident, in effect the depreciation has been deferred by one year. On this basis, an argument can be made that the depreciation is not saved, but the extension of the useful life of the asset has caused the deferral of the purchase of a new machine, which would result in a savings based on the time value of money related to the investment in a new machine. An issue with this approach is what happens if the insured decided to increase production after they resume operations? If this transpires, the purchase of the new machine may occur at the same time had there been no incident, which would result in no savings to the insured. Another issue is that this approach does not consider any future depreciation charges incurred by the insured on the purchase of the new machine. Given these issues, it begs the question, what is the proper approach?

The most common approach used is to assume that, due to the

incident, the depreciation on the machine has been saved because

the useful life of the asset has been extended and no depreciation

is actually incurred in the indemnity period (Year 2). This

approach is based on the argument that even though the replacement

of the undamaged asset may be deferred, the insured will incur

annual depreciation charges on either the existing undamaged

machine or a newly acquired machine. Therefore, if the insured has

no production activity during the year following the incident they

have saved a year's worth of depreciation.

For more examples and to read about partial saved depreciation,

read the full article in Canadian Underwriter.

Footnotes

1. In the straight line depreciation method, depreciation is charged uniformly over the life of an asset. We first subtract residual value of the asset from its cost to obtain the depreciable amount. The depreciable amount is then divided by the useful life of the asset in number of accounting periods to obtain depreciation expense per accounting period. Due to the simplicity of the straight line method of depreciation, it is the most commonly used depreciation method.

2. In the units of production method of depreciation, depreciation is charged according to the actual usage of the asset. In the units of production method, higher depreciation is charged when there is higher activity and less is charged when there is lower level of operation. Zero depreciation is charged when the asset is idle for the whole period. This method is similar to straight-line method except that life of the asset is estimated in terms of number of operations or number of machine hours etc.

(# of units produced in period / total life in number of units) x (Cost – Salvage Value)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.