Although the date on which Canada's Anti-Spam Legislation (CASL) may come into force is uncertain, the CRTC has issued two bulletins that provide guidance as to how to comply with the new law, once proclaimed in force.

But while some of the new guidance is helpful, other provisions will likely create significant operational concerns for businesses.

The Commission is the body charged with oversight and enforcement of most provisions of the new law, including the core provisions respecting commercial electronic messages (CEMs), alteration of transmission data and the installation of computer programs. In addition, the CRTC has the power to make regulations under the Act with respect to certain matters.

As we noted previously, the CRTC registered its Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations (CRTC) in March of 2012, providing additional clarification of these new regulations in a subsequent Regulatory Policy.

The first of the new Compliance and Enforcement Bulletins provides further, and in some cases helpful, guidance on the interpretation of these Regulations, such as providing details on acceptable unsubscribe mechanisms for each of email and SMS messages, including visual mock-ups of acceptable approaches.

However, the Bulletin also indicates that the Commission considers that, where included in general terms and conditions of use or sale of a product or service, requests to send commercial electronic messages, alter transmission data or download computer programs must be obtained through separate positive affirmations of the user, such as the proactive checking of a tick-box to signify consent to each of these actions, in addition to the acceptance of other contractual terms or an organization's privacy policy.

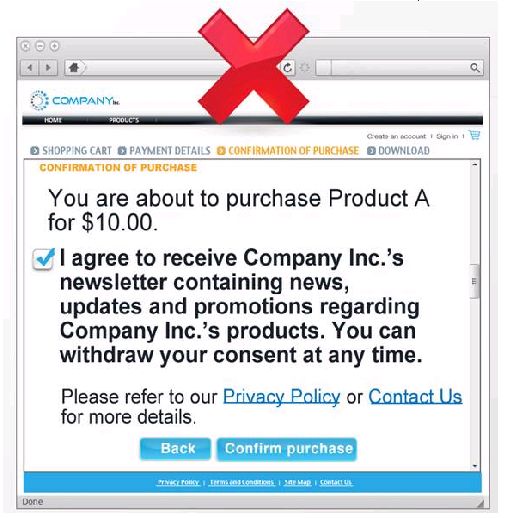

Most problematically, in a second Compliance and Enforcement Bulletin, the CRTC seems to be ruling out default settings that favour consent, even where the user can uncheck a box to exercise their choice (a process that the Commission refers to as "toggling") and where the user does provide a positive affirmation to a set of terms or an agreement. The following example, included in the Bulletin, shows that even where the pre-checked box and related consent is featured prominently, and is adjacent to a button that the user must pressed to signify agreement to a contract, the CRTC will not consider this to be valid consent to the receipt of CEMs under the anti-spam law.

Another area of likely concern for businesses relates to CRTC guidelines respecting the collection of oral consent, a form of consent which is explicitly authorized by the Electronic Commerce Protection Regulations (CRTC). The Bulletin suggests that in order to be able to discharge the onus of proving that it obtained oral consent, a business would have to have that consent verified by an independent third party or retain a complete and unedited audio recording of the consent.

We would note that, while these methods may work where consent is collected by telephone, through a call centre, they would create significant operational problems where consent is collected during a face-to-face interaction, such as might commonly occur at point of sale.

While the Bulletins do not have the force of law, they do provide a clear indication of how the CRTC will interpret the law and regulations that is charged to enforce.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.