For decades the project management profession has been emphasizing the need for sound methodology and comprehensive project management processes as being key to success. Additionally, change management1 and high performing teams2 have emerged as critical contributors to success. Indeed, the rate of project success has improved over the years, but the return on information technology (IT) driven business transformation projects is still disappointing many boards of directors.

Of all IT-based business projects surveyed in the Standish Group's 2009 Chaos Report, only 32% actually delivered the original project objectives on time and within budget. Twenty-four percent (24%) of projects failed completely, while 44% delivered a partial success, meaning they fell short of expectations in terms of the project scope, budget, and time line. 3, 6, 7

Why is project success so elusive?

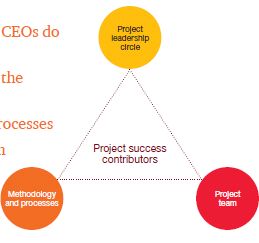

So what contributes to project success and what can CEOs do to avoid failures like this occurring on their watch?

This diagram depicts the three main contributors to the success of business transformation projects:

1. A sound methodology and project management processes

2. A skilled, experienced, and dedicated project team

3. An effective project leadership team

Let's briefly review each of these contributors:

1. Project management methodology and processes: Over the past thirty years, project management methodologies have evolved to encompass the experience gained by thousands of project teams. The Project Management Institute (PMI) has compiled and published the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK)4 comprising nine key project management processes. Most leading consulting organizations have also developed their own comprehensive business transformation methodologies.5

2. High performing project team: A skilled, experienced, and dedicated project team can make all the difference to the success of a project. Charles Garfield's book, Peak Performers: The New Heroes of American Business,2 published in 1986, is as relevant today as it was 25 years ago. Building a collaborative project environment that encourages the team to take ownership, be creative, and deliver high quality results pays dividends beyond expectations.

3. The project leadership circle: This is the most important, yet least recounted, contributor to project success. The leadership circle is the small group of people, typically appointed by executive management to direct the project towards achieving its objectives on time and within budget.

This third success ingredient has not attracted the attention of the project management profession, perhaps because of its sensitive nature. While sound methodology and a high performing project team are necessary, they are not sufficient to ensure success. In this paper, we offer a new perspective on the role of the project leadership team as a critical contributor to the success of business transformation projects. We provide real life examples that illustrate the role of the project leadership team, and recommendations for addressing the management challenges facing most projects. The remainder of this paper focuses on the leadership circle and the attributes that, if possessed by the leadership circle, will immeasurably enhance the success of the project.

The leadership circle: how does it come about?

Case study 1: The birth of a leadership circle

It was time again for the ABC Company's executive committee to hold its all-day quarterly meeting. After hours of deliberation, the much needed, once-in-a-generation project to transform the company's sales processes and systems was finally approved. Before they adjourned they had one remaining item on the agenda: they had to select the person who will lead this very challenging project. Somebody pulled out an organization chart and after a five minute discussion they decided that John, the up-and-coming young vice president (VP) of marketing, will be a good fit for the job. The next day the executive vice president (EVP) of sales and marketing met with John to discuss his new assignment. The EVP emphasized the mission-critical nature of the project, saying that the future of the company was riding on its success. While the EVP was still talking, John was already mentally considering the ramifications of his new assignment. If he could pull this off, he could be the youngest EVP the company had ever known. But he had never managed a business transformation project before, not to mention a large and complex one as this, and his plate was already very full. He was also often out of the office, travelling three weeks each month. The EVP however had faith in John's abilities and so with a few reassuring words, the deal was sealed.

John's first task was to form his project leadership circle, represented in the diagram below. After hours of negotiation he managed to secure the part-time involvement of two sales directors and a director from the IT group. The only project manager he could find was someone like him, bright and committed, but with little experience in running large and complex projects. The software company supplying the packaged solution could not offer any salvation either. The only project lead they could offer was a highly qualified technical expert (who was in critical need), but with little to offer in the way of project management experience. (See page 6 to continue).

The leadership circle structure

The leadership circle is the management team that is charged with the responsibility to direct a business transformation project and lead the project to its successful completion. It typically reports to the executive committee and interacts closely with stakeholders at all levels of the organization. The leadership circle usually comprises the following team members:

- The project sponsor, who has the overall responsibility for the project

- The business leads, who represent the business operations or departments affected by the project

- The project manager, who is responsible for the planning and day-to-day management of the project

- The technology or IT manager(s), who support the project's technology requirements

- The vendor's manager, who represents the software, hardware, or consulting supplier contracted to help the company on the project

The composition of the leadership circle may vary depending on the specific demands of the project.

The leadership circle's mandate

After the leadership circle is set up, the leadership team's mandate and key responsibilities need to be defined. A sample set of responsibilities is outlined below:

1. Confirm and expand on the overall goals and strategy for the project

2. Lay down the foundation for the project, including scope, approach, resources, timeline, cost, organization, and management processes

3. Provide day-to-day direction to the project team

4. Engage the key project stakeholders

5. Anticipate and resolve critical issues before they occur.

Case study 1: The birth of a leadership circle (continued)

As the project sponsor, John's first challenge came soon after his assignment, as he started negotiating with the regional VPs of operations to secure the participation of representative users, or subject matter experts (SMEs). Unfortunately, all he could negotiate was one part-time SME from each of the four global regions. The regional VPs told him that they were running a very tight ship, and that they could not possibly assign their experienced staff to work on the project. A frequent response that John received was that the software consultants could design the new system and when necessary, the consultants could spend a couple of hours a week with the SMEs. Facing the same resistance from all four regional VPs, John was ready to build a project organization based primarily on outside consultants.

However, a golf course conversation the following Sunday changed his mind. He was talking to a personal acquaintance who had just completed the deployment of a large process transformation project. His acquaintance warned him that one of the greatest risks is an inadequate representation of the business on his project, and that John should have a serious conversation with his CEO about it.

The next few weeks proved to be very difficult for John, as he mustered every ounce of courage and skill he had in negotiating with the company's executives. He even considered resigning at one point. But in the end he was able to secure 60% of his project resources. A year later, John confessed to the same acquaintance that without his advice, the project would have been a dismal failure.

Amongst the first challenges the project leadership faces is getting buy-in and commitment for resources within the organization. It is however important to confront and overcome this challenge in order to poise the project for success.

The five attributes of success

There are five key attributes that the leadership circle should collectively possess to ensure the successful completion of their project. A graphical representation of the leadership circle, and the attributes for success, is presented below.

1. Experience

There's no substitute for experience. The ability to anticipate future challenges that may be facing the project, and offer a proven resolution to difficult situations cannot be acquired in any other way.

Mostly, companies undertake major transformational projects once in a management generation, resulting in the scarcity of experienced transformation leaders within the company. So executive management is left with no option but to assign project leaders who may be very good functional managers (e.g. sales, production or finance), but have little project leadership experience. Since executive managers themselves often lack experience in leading large and complex projects, they assume that general management experience will suffice as a qualification, and that the gap in experience can be learned on the job.

Case study 2: The value of experience

The following case study illustrates the value of experience. The business director who was assigned to the project was a very intelligent individual and was very knowledgeable in the business's operations. A few months into the project, he decided to call in the sales consultant from the software company to provide an expert opinion before they finalized the direction for the project. The sales consultant presented an alternative approach to the one they had originally contemplated. The software demo was impressive, and the sales consultant's arguments were convincing. So after some deliberation, the project director instructed the team to change the original approach and adopt the consultant's recommendation.

The software company brought in three consultants to reconfigure the software, using the new approach. They said it should take only a couple of weeks to complete. At the status meeting four weeks later, the consultants reported some difficulties and asked for an extension of four weeks. Two additional experts were brought in, and the high intensity efforts continued. Four weeks had passed, followed by another four weeks, after which another extension was requested. It was becoming increasingly clear that the software package could not be configured to meet the company's requirements using the sales consultant's approach, and that the original direction was the right one after all. Finally, after four months, the project director decided to pull the plug on the sales consultant's solution, and directed the team to revert to the original approach.

The cost of the four month detour was over $6 million, not to mention the loss of credibility of the project leadership and the loss of user support for the project as a whole.

When appointing the leadership circle, executive management should consider the following two questions:

1. Proven track record: Does the leadership team have the collective knowledge, skill, and experience of successfully delivering a project of this size and complexity? (A threshold of having led a project of at least 60% of the size of the project at hand should be considered).

2. Anticipatory capabilities: Does the leadership team have the ability to anticipate critical issues, provide valuable insight, and make appropriate decisions in challenging situations?

2. Authority

Executive management often assume that the mere assignment of the project responsibilities followed by a corporation-wide email announcement will endow the leadership circle with the authority required to transform the entire organization.

To ensure the success of the transformational project, it is incumbent on executive management to critically review the following questions before finalizing their selection of the leadership circle:

1. Authority: Does the leadership team have the authority to make transformational decisions that will impact the entire organization?

2. Influence: Does the leadership circle have the influence to secure the buy-in of all key stakeholders?

Case study 3: Making change stick

In this case study, the objective of the project was to implement new business processes to be followed by field managers worldwide. The new processes entailed capturing standard operational data by field managers, followed by analysis and incremental process improvements to be implemented by a corporate process improvement team. A group of SMEs was hand-picked by the project director to represent the field. The new business process was meticulously designed and the new system was flawlessly constructed on time and within budget. The time to roll out the system arrived. Training sessions were held and the field managers were instructed on how to use the new system. A few months passed and the corporate process team noticed that the field personnel were not really entering the requisite data into the system. Meetings were held with the field leadership, only to discover that the field personnel were focused on meeting the performance objectives set by their line supervisors and did not have the time or the inclination to follow the new process imposed by corporate management. After a long period of trying to rectify the situation to no avail, the project director realized all too late that he did not have the authority or the influence to make the change stick.

3. Alignment of objectives and priorities

The third success attribute that executive management has to pay attention to is ensuring that the objectives, priorities and interests of the individual members of the leadership circle are aligned with those of the project and the organization as a whole. It's critically important to ensure that no significant irreconcilable differences of opinion exist within the circle regarding the project objectives, scope and approacheither expressed or hidden.

Had the executive committee in case study 4 spent the time to review the interests and priorities of the project sponsor more carefully, they may have uncovered his strong attachment to the old, custom-built system. When reviewing candidates for the leadership circle, executive management should consider the following questions:

1. Alignment: Are the objectives, priorities, and interests of the leadership team fully aligned with those of the project?

2. Conflicts: Do the leaders have any major conflicting objectives, priorities or interests?

3. Engagement: Are the leaders fully engaged in the project and are they able to spend the requisite amount of time leading it?

Case study 4: When personal interests get in the way

A global, multidivisional company decided to standardize their information systems across all divisions. The executive committee decided to appoint the head of one of the divisions to lead the project. Their rationale was that he was very experienced in implementing large software-driven transformations. Six months later, it became clear that the appointment was a mistake. The project leader's division had been using an antiquated but heavily customized software package to which they had become very accustomed over the years. But the majority of the company's divisions were using another package, which upon a detailed evaluation proved to be much more suitable for the company as a whole. Everyone soon realized that the attachment of the project leader to his existing software package had become a major impediment to the project. After painful consideration and a three month delay, the project leader had to be removed and a new, more impartial, leader was appointed.

Had the executive committee in case study 4 spent the time to review the interests and priorities of the project sponsor more carefully, they may have uncovered his strong attachment to the old, custom-built system. When reviewing candidates for the leadership circle, executive management should consider the following questions:

1. Alignment: Are the objectives, priorities, and interests of the leadership team fully aligned with those of the project?

2. Conflicts: Do the leaders have any major conflicting objectives, priorities or interests?

3. Engagement: Are the leaders fully engaged in the project and are they able to spend the requisite amount of time leading it?

4. Thoroughness in execution

If you're thinking that the success attributes of the leadership circle are becoming increasingly difficult to assess, you're right. Thoroughness in execution is about engendering a culture of adherence to methods, process and discipline. The use of a robust methodology ensures that the collective knowledge that evolved over years of managing transformation projects is being used to benefit the project's outcome. Some organizations are very mature in the way they embrace methodology and process, while others are more reactive, which places them at a much lower level on the capability maturing curve.

Case study 5: The critical role of methodology and process

In this case study, senior government officials decided to implement a major technology-based border security system. In their eagerness to show quick results the project executive "sole sourced" the project, awarding it to a single generally reputed supplier, but with little experience in the project's subject matter. The only stipulation was that the pilot stage of the project had to be completed by the end of the year. Anticipating the huge contract that was to follow the pilot, the supplier submitted its proposal which met the ridiculously short timeline. To meet the compressed time line, the supplier skipped the requirements definition phase and did not even allow for time to talk to the field agents that will ultimately use the system. A year later, after incurring hundreds of millions of dollars, the pilot had to be cancelled since it did not meet the conditions in the field and the requirements of the border patrol agents.

In case study 5, could the use of a due process have avoided this outcome? While the correct response to this question is difficult to determine, it is likely that the problems would have been discovered much earlier, perhaps during the requirements definition phase of the project.

The key questions that executives have to ask are:

1. Culture: Does the culture of the organization generally support process and methodology?

2. Discipline: Is the leadership circle disciplined and structured in its approach? Will members of the circle embrace and drive the adoption of processes and methodology?

3. Courage: Will the leaders have the courage and conviction to resist the temptation to take undue shortcuts in the process?

5. Relationship dynamics

Perhaps the most difficult success attribute to predict is the relationship dynamics within the leadership circle. Unless the leadership team has already worked together before, it is very difficult to predict how they will relate to each other, particularly in the high pressure project environment that will ensue.

Without a positive working environment, a project's success is in serious jeopardy. But a healthy balance is not easy to achieve. On the one hand selecting strong and experienced personalities to lead the project is an imperative, but on the other, a project leadership circle comprising opinionated individuals who cannot listen to dissenting opinions is not conducive to success.

Case study 6: Relationship dynamicsthe most important attribute of all

A project executive sponsor, who was a VP in the organization, did not have any experience in running business transformation projects, but he was determined to listen and learn. His project leadership meetings used to take twice as long as typical meetings. The VP would go around the room, seeking inputs from each member of the team, listening attentively and taking notes. He would then retreat to his office, consolidate the views he had just listened to, superimpose his own thoughts, and come up with his well-considered plan of action. He went out of his way to engender an open team environmentone that made even the most junior members of the team feel safe in expressing their views, even if they were contrary to the views of the more senior members of the team.

As the project evolved the value of this collaborative and open approach became clear to the project team and to executive management. The quality of the decisions made by the project leadership team and the stakeholder support for these decisions became the hallmark of the project.

A typical leadership circle consists of some senior managers and some more junior members. In many cases, the more junior members of the team may be more experienced in certain technical and project management aspects of the project. If the junior members of the team do not feel invited or safe to express their opinions, especially dissenting ones, they will be unlikely to speak out, perhaps internalizing information that might have otherwise helped the project avoid a troubled outcome.

Clearly, executive management may not always have the ideal candidate to lead the project, and they may have to compromise. But it is incumbent on them to carefully consider the relationship dynamics of the team, since a dissonant team can severely compromise the project's success. Here are the questions to ask:

1. Respect: Will the leadership circle be open, respectful, tolerant and supportive of each other?

2. Dissenting opinions: Will members of the team feel safe in expressing dissenting opinions?

3. Junior members: Will the opinion of the junior, but sometimes more experienced, members of the team be actively sought and taken into consideration?

Supporting an existing leadership circle

Executive management has a crucial role in developing the capabilities and improving the performance of the leadership circle during the life of the project. The following three-step approach can markedly help the leadership circle in performing its responsibilities:

1. Assess: Candidly assess the strengths and weaknesses of the team with respect to the five success attributes: Experience, authority, alignment of objectives, thoroughness in execution, and relationship dynamics.

2. Train: Provide the team with awareness training on the five attributes.

3. Coach: Implement a capability coaching program that will help the team build on its strengths and overcome its weaknesses.

Investing in the leadership circle will pay handsome dividends to the success of the project and to the company as a whole.

In summary

The three contributors to the success of IT-driven business transformation projects are:

1. A sound methodology and project management processes

2. A skilled, experienced and dedicated project team

3. An effective project leadership team

The third contributoran effective leadership teamis often ignored by the project management profession, yet it is as important as the other two success factors.

When embarking on a business transformation project, we recommend that executive management establishes a selection committee to interview and select the most appropriate team for the project leadership circle.

To ensure the project's success, the selection committee should consider the following five attributes of the leadership circle:

1. Experience: a track record of successfully managing similar projects

2. Authority: the authority and influence to implement change within the organization

3. Aligning objectives and priorities: ensuring that the objectives and priorities of the leadership circle are aligned with those of the company and the project

4. Thoroughness in execution: the ability to engender a culture of adherence to methodology and process and the courage to resist undue shortcuts in the face of business pressures

5. Relationship dynamics: equality amongst team members, the ability to work together constructively with relationships built on mutual respect

If the leadership team is already in place, the best way to achieve success is by identifying weaknesses and addressing them through coaching and training.

Footnotes

1. Todnem, R. (2005). Organisational Change Management: A Critical Review. Journal of Change Management, Volume 5.

2. Garfield, Charles. (1986). Peak Performers. The New Heroes of American Business. Avon Books, New York.

3. The Standish Group, (2009). The Chaos Report. Boston, MA April 23, 2009.

4. Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide) - Fourth Edition.

5. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLC, (PwC), Transform Methodology,

6. Levinson, Meredith. (2009, June 18). CIO.com. Recession Causes Rising IT Project Failure Rates. Retrieved from http://www.cio.com/article/495306/Recession_Causes_Rising_IT_Project_Failure_Rates_ on March 16, 2012 .

7. Kappelman, Leon A. (2011, Feb 19). The early warning signs of IT project failure. ASEE Annual Conference.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.