The new 'Requests for flexible working arrangements' National Employment Standard (the right to request NES) introduced with the Fair Work Act 2009 (Act) has led to much debate in recent weeks. There is some fear that the right to request NES is too broad and will place extra pressure on employers.

This article looks at the current entitlement of employees with family or caring responsibilities under Federal, State and Territory discrimination legislation to flexible or part time work and considers the changes that the new right to request NES will bring – is it worth being so concerned about? The Curent Federal system

Section 28 of the Workplace Relations Act 1996 (Cth) (the WR Act) provides a return to work guarantee for mothers after maternity leave. However, there is no specific entitlement or right under current Federal or State legislation for a person to request or be entitled to flexible working arrangements (in the context of child care responsibilities or otherwise).

In the absence of any contractual term dealing with the issue, protection for workers seeking flexible working arrangements comes from the existence of the right to bring a claim for direct or indirect discrimination under either Federal or State legislation. This is on the basis a request for flexible working arrangements has been denied.

At the Federal level and under the Sex Discrimination Act 1986 (Cth) (SDA), there are three options available to a person whose request for flexible working arrangements has been denied.

The first is to bring a claim alleging direct discrimination on the basis of family responsibilities. However, such a claim can only be brought under the SDA where the discrimination results in termination of employment. The Federal Magistrates Court has held that termination of employment extends to cover cases of 'constructive dismissal' (see Evans v National Crime Authority [2003] FMCA 375). The prohibition on discrimination on the basis of family responsibilities does not extend to other areas of the employment relationship. Under section 4 of the SDA, 'family responsibilities' are defined to include caring for and supporting 'other family members' as well as children.

The second option is to bring a claim alleging direct or indirect discrimination on the basis of sex. The prohibition on discrimination on gender grounds in the area of employment is broader than that for family responsibilities. It extends beyond termination of employment to include: the terms or conditions of employment; denying the employee access, or limiting the employee's access, to opportunities for promotion, transfer or training, or to any other benefits associated with employment; or subjecting the employee to any other detriment.

The third option is to bring a claim alleging direct or indirect discrimination on the basis of pregnancy. Obviously, however, this option is only open to women whose request for flexible working arrangements is tied to pregnancy or a characteristic that generally applies to pregnant women, such as taking maternity leave. It does not extend to men or other caring responsibilities that create a need for flexible working arrangements.

Under the current Federal system, it is possible for an employer defending a claim of indirect discrimination on the grounds of sex or pregnancy to avoid a finding that the imposition of a particular condition, requirement or practice, or refusal of a request, is discriminatory if it was reasonable in the circumstances. The onus of establishing reasonableness is placed on the employer. Note that this protection only applies in the context of indirect discrimination.

The Current State System

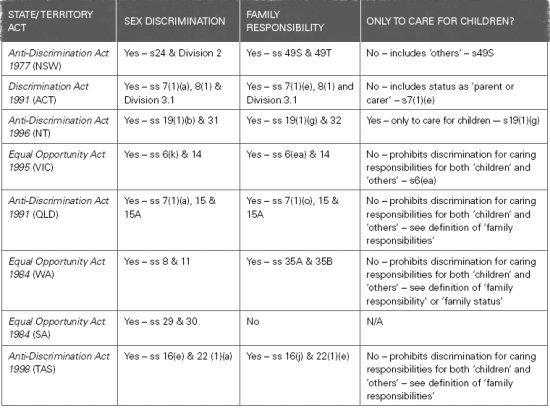

The following table sets out whether State and Territory discrimination legislation currently prohibits discrimination on the ground of sex and/or family responsibilities in the area of employment. If 'family responsibilities' or 'caring responsibilities' is included as a ground, then the issue of whether the ground includes caring for children only or others also is noted in the final column:

The State system provides similar coverage to the Federal system in relation to sex discrimination. However, when it comes to allowing for a claim of discrimination to be made on the basis of caring or family responsibilities in relation to most aspects of the employment relationship, not just in the context of termination of employment, the current State system (except in South Australia) provides broader coverage.

The Right To Request NES

The National Employment Standard titled 'Requests for flexible working arrangements' provides an employee, who is a parent and has the care of a child under school age, with a right to request a change in working arrangements for the purpose of assisting the employee to care for the child.

An employee can make a request once they have completed at least 12 months of continuous service with the employer. Casual employees must be engaged on a regular and systemic basis for at least 12 months prior to making a request and must have a 'reasonable expectation' of continuing engagement on this basis.

A request must be in writing, set out the details of the change sought and the reasons for it. The employer must provide a written response to a request within 21 days stating whether the request is granted and if it is refused, the reasons for the refusal. The employer may only refuse a request on 'reasonable business grounds'.

What Are The Changes And What Do I Need To Do?

The change is mainly a procedural one. Employees now have a right to request flexible working arrangements in a particular fashion. This is opposed to a right to bring a discrimination claim if refusal of a request was discriminatory on a prohibited ground in a prescribed area of employment. Note that the right to request NES is available to both men and women who are parents and have the care of under school age children. The new procedural requirements around requests are the most significant change and as such, employers need to familiarise themselves with those requirements now.

There is, however, only one significant change in terms of granting requests. Under the current system, an employer is able to refuse a request for flexible working arrangements if doing so is reasonable in the circumstances, provided that they treat all employees who make requests in the same way. The right to request NES adds the additional element of 'business' to this consideration process. That is, an employer may refuse a request on 'reasonable business grounds' not just 'reasonable grounds'. The introduction of the word 'business' is significant in the sense that considerations of 'reasonable grounds' may encompass a wide range of issues, taking into account the employee's interests as well as the employer's. Limiting the concept to 'reasonable business grounds' focuses the consideration on the interests of the employer and its business.

The operation of the State legislation in relation to discrimination on the grounds of sex and family or caring responsibilities will continue. Under clause 66 of the Act, where State or Territory legislation provides entitlements on flexible working arrangements which are more beneficial to the employee than the right to request NES, the State and Territory legislation will prevail.

The more significant changes in the Act are the new sections prohibiting discrimination in employment and adverse action against employees because they have a 'workplace right'. It is from these new areas that protection for workers who wish to utilise flexible working arrangements (because of caring responsibilities, for children or others) might be significantly increased. It is these concepts employers should focus their energy on as there is room for no cost, easy access litigation in the Fair Work division of the Federal Magistrates Court in relation to these new areas. The right to request NES largely reflects the Federal system as it stands and mainly imposes procedural requirements on employers, making some of the fear and concern surrounding its introduction look like a storm in a tea cup when compared to other changes the Act will introduce.

Phillips Fox has changed its name to DLA Phillips Fox because the firm entered into an exclusive alliance with DLA Piper, one of the largest legal services organisations in the world. We will retain our offices in every major commercial centre in Australia and New Zealand, with no operational change to your relationship with the firm. DLA Phillips Fox can now take your business one step further − by connecting you to a global network of legal experience, talent and knowledge.

This publication is intended as a first point of reference and should not be relied on as a substitute for professional advice. Specialist legal advice should always be sought in relation to any particular circumstances and no liability will be accepted for any losses incurred by those relying solely on this publication.