Given the UK experience, it's fair to predict that Agencies will have to ramp up their system integrator skillsets, which means more ongoing management of multiple vendor projects.

For the best part of a decade since Sir Peter Gershon was engaged to review Commonwealth ICT procurement in 2008, the Australian Government has been looking to the United Kingdom for inspiration in IT procurement policy, so it makes sense to look to the UK for lessons on implementation of those policies.

In this article we'll see how this policy has played out in the UK, and why Agencies should be looking at revamping and strengthening the linkages between corporate governance, contract management and system integration.

The UK approach: caps and red lines for ICT procurement

A cap on the value of UK Government ICT contracts was implemented initially in the UK Government's 2012 Procurement Policy Note 02/12 that sets out its approach to cap IT contracts at less than £100 million in lifetime value through a presumption when designing IT projects that they should have a cost of less than this threshold, unless a strong case can be made that doing so increases the overall cost, including through increased risk of failure or security threats.

This policy approach was strengthened in 2014, when the UK Government announced a number of "red lines" for approval of ICT contracts, including requiring that no ICT contract be over £100 million in value unless there were "exceptional reasons". The underlying policy was intended to tackle "abusive" behaviour by IT suppliers, with comments by the UK chief procurement officer that they were designed to break down the "oligopoly" of big suppliers and ensure a more competitive environment in which more small and medium enterprise (SME) providers could take part.

Other red lines established are:

- ensuring systems integration and service delivery roles were not performed by the same vendor;

- preventing automatic contract extensions;

- limiting hosting contracts to two years; and

- requiring agencies to follow a Technology Code of Practice.

The Technology Code of Practice includes a requirement that where economic ICT contracts include a break clause at a maximum of two years, allowing termination with minimal exit costs. The UK Government recently reaffirmed its commitment to eliminating large single-supplier multiyear IT arrangements in its 2017 Government Transformation Strategy.

These rules are enforced by the UK Government through budget spending controls, administered by Government Digital Services (GDS). The spending controls apply to both digital services (online delivery to non-government users) and technology services (internal facing service delivery), with approval required based on the type of service and the level of spending, but broadly requiring that all significant ICT contracts be approved by GDS. GDS is also responsible for a broad ICT coordination role across the UK government.

How effective has the policy been in the UK?

When introducing the red lines, the Minister for the Cabinet Office noted that the government had already made good progress in opening up the SME market1, with the establishment of a new procurement framework for building digital public services ? where 84% of contracts by volume were awarded to SMEs. The red lines were intended to further build on this progress and break up large multi-year arrangements.

However, it's not clear that the measures have had their desired impact on SME involvement. The UK National Audit Office (NAO) concluded in its March 2017 report "Digital transformation in government" that while these measures targeting SMEs have some impact, most government procurement with digital and technology suppliers continues to be with large organisations. While recognising the role of the new procurement frameworks the UK Government established, it noted 94% of such ICT spending was still with large enterprises in 2015-16, which is only 1% less than before these policies were introduced in 2012-13.

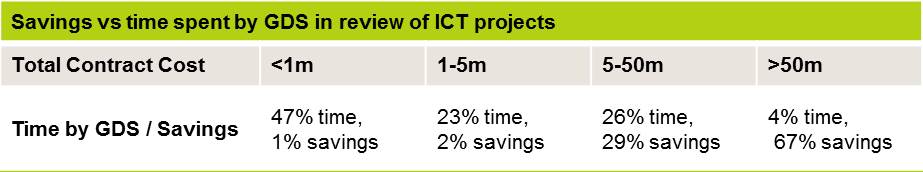

While the impact on SME involvement has not been extensive, there is evidence that tighter budget controls implemented by GDS had a net saving effect, with an estimated £1.3 billion saved over five years to 2016. The vast majority of this saving was from work done by GDS in reviewing ICT projects over £5 million. It was noted by the NAO that while 70% of time was spent by GDS on review and approval of projects under £5 million, this contributed only 3% of the savings.

Where are exceptions to the policy applied in the UK?

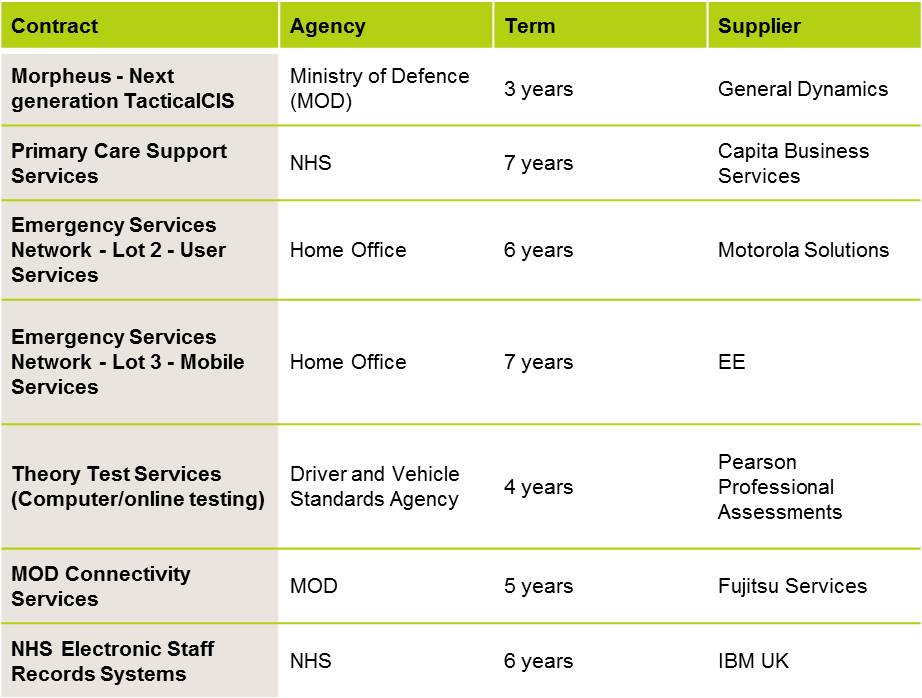

Although the UK Government's red lines and presumptive approach to developing ICT projects have now been in place for a number of years, there are still examples where long-term ICT contracts are entered into by UK Government agencies above the £100 million threshold.

Some examples of such contracts since 2014 include:

The contracts recently entered into by the MoD for connectivity services have received particular attention. As part of a transformation project by MoD, estimated to save £1 billion over 10 years, £1.5 billion in contracts are being awarded to Fujitsu and separately to a consortium that also includes Airbus Defence and Space and CGI. Further significant MoD procurements in the telecommunications space are also expected. The MoD has stated that the nature and size of the department's IT projects meant that they could only be fulfilled by such major IT firms, with SMEs lacking scale and resources to meet their technology requirements, and these arrangements allowing MoD to be more efficient and cost-effective.

In addition to these examples of large vendor contracts, it should be recognised that there are also a large number of very high value framework and call-down arrangements being entered into by UK Government, these are essentially panel arrangements that commonly include major IT vendors.

What does this mean for Australia Government ICT procurement?

The measures announced by the Australian Government are the most visible early step to adopt the Taskforce's recommendations, with the aim of assisting SMEs to bid for more Commonwealth work, but also to drive efficiencies and reduce the risk of ICT procurement. They are likely to be implemented as part of further clarification to Commonwealth IT procurement policies that were also recommended by the Taskforce, perhaps via co-ordinated approval processes similar to that in the UK.

There are still a number of aspects of the new measures that require more detail from the Government - for example, how they apply to less significant contracts and software licences (which are often perpetual), and whether the three-year limitation can be satisfied through securing appropriate termination and exit rights.

While the likely impact of the measures on SME involvement is unclear (based on UK experience), it is likely to drive the APS towards smaller contracts that potentially carry less risk from single vendors.

Given the UK experience, it's fair to predict that Agencies will therefore have to ramp up their system integrator skillsets, which means more ongoing management of multiple vendor projects.

The key thing for Agencies to be doing now in readiness is to connect the dots in its management strategies, especially:

- evaluate IT procurements: are there large procurements on the horizon or in progress that are better managed as multiple smaller vendor contracts, or does a need exist to enter into a larger single vendor arrangement that will require approval?

- procurement rules: build and maintain a robust culture of compliance with the ethical and legal requirements of Commonwealth procurement, including the new processes for complaints-handling that are coming soon;

- corporate governance: ensure you're complying with the over-arching corporate governance obligations under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (Cth); and

- contract management: resource your teams to manage the contract, and run the rule over your contract management practices ( are records being created and kept? do your teams know not to depart from contract terms informally?)

RELATED KNOWLEDGE

- Overhaul of Commonwealth procurement on the way, so get ready now

- Building a better ICT procurement process: the impact on Australian Government Agencies

- Building a robust system for managing conflicts of interest in procurement: lessons from the ANAO

- Loose lips sink ships (and service level agreements): the impact of your communications in managing your contract

- The Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act: implications for CAC bodies

Footnote

1SME is defined in the UK context under EU Recommendation 2003/361, as a business with fewer than 250 employees, and either (i) turnover of no more than 50 million euros; or (ii) a balance sheet of no more than 43 million euros.

Clayton Utz communications are intended to provide commentary and general information. They should not be relied upon as legal advice. Formal legal advice should be sought in particular transactions or on matters of interest arising from this bulletin. Persons listed may not be admitted in all states and territories.