- within Corporate/Commercial Law, Law Department Performance, Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

- with Inhouse Counsel

- in United States

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit, Business & Consumer Services and Media & Information industries

Introduction

Transparency International has released its Corruption Perceptions Index 2016. The index assesses how clean or corrupt a country's public sector is perceived to be.

On 31 January, KordaMentha Forensic hosted the Australian launch of the index at our offices in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane and Perth. At those events, an audience of regulators, corporates and investigators discussed key observations from the 2016 index as well as practical suggestions for Australia's continued anti-corruption efforts.

In this article, Katharine Toney, an Associate Director in our Sydney office, continues the discussion.

- What is the Corruption Perceptions Index?

-

The Corruption Perceptions Index is one of Transparency International's key tools for assessing the nature and scope of corruption across the globe. Launched every year since 1995, it is a composite index, using data collected by a variety of reputable institutions, including the World Bank.

There are two important factors about the index:

- It is based on perceptions. Given the illicit, secretive and often-complex nature of corruption - combined with the fact that corruption can have both financial and non-financial implications - any attempted measurement of corruption can only ever be approximate. But research suggests that the perception of corruption by those people in a position to assess it - such as business people and country experts - provides a reliable estimate of the level of corruption in a country.

- While Transparency International's other work does consider the private sector, the scope of the Corruption Perceptions Index is strictly limited to a country's public sector.

- Insights from the Corruption Perceptions 3 Index 2016

-

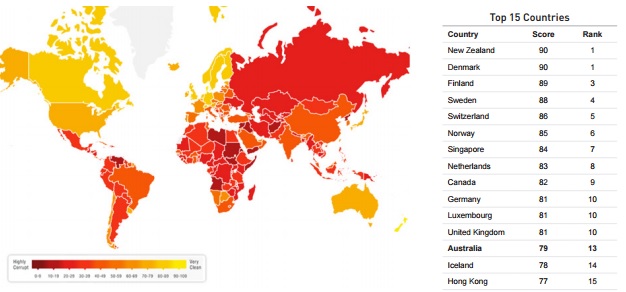

For the 2016 index, 176 countries and territories from around the world were scored and ranked, with possible scores ranging from 0 ('highly corrupt') to 100 ('very clean').

The results are mapped below.

Key facts from the 2016 index include:

- New Zealand is in joint-first place with Denmark as having the lowest perceived public service corruption. Denmark has achieved this feat every year since 2012, while New Zealand achieved first or joint-first position for seven consecutive years until 2013.

- Australia's score (79 out of 100) and rank (13th) are both unchanged from 2015, after three years of decline prior to this. Australia has been out of the top ten perceived-cleanest countries since 2014.

These results raise a number of questions in relation to the perception of corruption in Australia compared to other countries:

- What is New Zealand doing right?

- Why has Australia fallen out of the top ten in recent years?

- What can Australia do to improve its score to that of previous years?

- What is New Zealand doing right?

-

How is one of our nearest neighbours regularly out-performing us on the corruption front?

Transparency International attributes the success of the high-performers in the index to the characteristics of open government, press freedom, civil liberties and independent judicial systems. New Zealand's Justice Minister has credited her nation's 2016 ranking to a series of government initiatives, including the strengthening of foreign bribery offences in response to OECD recommendations, the ratification of the United Nations Convention Against Corruption, a review of extradition laws and the fast-tracking of anti-money laundering reforms. Many of these reforms stem from the Organised Crime and Anti-corruption Legislation Bill, which was passed into law in November 2015.

One key difference between Australia and New Zealand in our approaches to anti-corruption stems from our federal versus unitary state systems:

- In New Zealand, the agencies fighting corruption do so at the national level. These primary agencies are the Serious Fraud Office and the New Zealand Police.

- In Australia, each state has its own independent specialist anti-corruption agency, each with significantly different definitions of corruption and with widely varying investigation and prosecution powers.

Transparency International believes that public confidence in Australia's integrity systems relies on resolving the discrepancies between Australia's state anti-corruption agencies.

- What has Australia being doing wrong?

-

At 13th position on the index in 2016, Australia remains outside the top ten for the third consecutive year.

This follows a steady decline between 2012 and 2015 in both score and rank.

In recent years, Australia's performance on the index has been marred by revelations of foreign bribery scandals such as those of Securency Limited and Note Printing Australia (NPA), various parliamentary expense scandals, and perceived inaction from successive governments "who have failed to address weaknesses in Australia's laws and legal processes". Among those laws is Australia's foreign bribery legislation, which lags behind the UK Bribery Act and the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) in terms of enforcement and penalties.

For 2016, Transparency International has cited the following as likely causes of Australia's failure to 5 improve its score and rank:

- The continued absence of convictions under the foreign bribery provisions of the Criminal Code Act;

- The suppression orders in relation to the Securency/NPA case, which have prevented external organisations from evaluating Australia's progress with its anti-bribery efforts; and

- Threats to independent institutions". In this context, the report mentions attacks by the government on the credibility of the president of the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC), Gillian Triggs, following the AHRC's report into abuse in detention centres. According to Transparency International: "such intimidation undermines the independence of institutions like the AHRC, which are critical to functioning democracy.

What, then, can be done to buck the downward trend of recent years, and to see Australia in the top ten least-perceived corrupt countries once more?

- What can Australia do to improve its performance in the CPI?

-

For the past several years, Transparency International has recommended that the Australian government establish a federal anti-corruption agency as one element of an improved multi-agency strategy. It has also recommended the reform of anti-corruption and political finance regimes across state, territory and federal governments in order to make them more consistent.

On 13 January 2017 Prime Minister Turnbull announced the establishment of an independent parliamentary expenses authority to administer and oversee the work expenses of members of parliament. But this addresses only a small part of the problem.

Other recent progress has been made, with Australia joining the Open Government Partnership (OGP) in 2015 and the publication of the country's first OGP National Action Plan on 8 December 2016. Within the 64-page plan are fifteen broad-ranging statements of intent from the government, which are summarised below. The target is for all of these to be implemented or substantially-implemented by July 2018.

Still more can be done, and in response to the 2016 index results Transparency International Australia has announced the launch of its first ever biennial conference, the National Integrity 2017. The two-day event, co-hosted by Griffith University, will aim to bring the public and private sectors together to discuss how Australia should strengthen its anti-corruption bodies and the role that companies, governments and other institutions can play in achieving this.

The National Integrity 2017 will run from 16-17 March 2016 at the Novotel, Brisbane. Details and registrations can be found at http://events.griffith.edu.au/nationalintegrity2017.

- Conclusion

-

The Corruption Perceptions Index 2016 shows that every country in the world has scope to improve the perception of the level of corruption in its country's public sector; no country is completely immune from perceived corruption.

The Australian government's statements of intent in its first Open Government Partnership National Action Plan are an encouraging start in efforts to reverse the country's downward trend in the index in recent years; implementation of this plan is now key.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.